44 minute read

Profit

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Advertisement

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Shaking off the ashes of Airlift and Swvl, BusCaro looks to have a crack at the commuting and mobility space with a twist

By Daniyal Ahmad

If someone walked up to you today and said there was a new startup in town that was going to disrupt mass-transit with a low-cost, techheavy, bus sharing model what would you say? Unless you’ve been living under a rock since 2018, the immediate reaction for most would be a surprised exclamation of “again?”

Yet here we are again. BusCaro, a mass-transit solution startup, has recently entered the market that was left vacant by Airlift and Swvl at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. At this point in the short history of Pakistan’s startup ecosystem both startups have become a cautionary tale in how not to spend VC money.

The names are thrown around anytime there is a conversation regarding aggressive growth, the importance of good business fundamentals or spending exorbitant amounts on customer acquisition. Which is why one would expect any new startup to stay away from an idea that has failed twice in the Pakistani market with a ten-foot pole.

Which means there must be something different that BusCaro is doing. So what is that something different exactly? And with funding already on the chopping block for Pakistan, how can BusCaro be a startup that says Bus Karo to burning venture capital?

The Airlift, and Swvl post-mortem

Any discussion of what BusCaro can, or cannot, do merits a trip down memory lane first. Albeit a thorny one, but we’ll be brief.

“The most formidable obstacle encountered by inter-city bus companies in the mobility transport sector is the fierce competition from alternative modes of transportation in

Pakistan. Qingqis, rickshaws, and motorcycles are modes that are unique to the developing world, and are even more prevalent in Pakistan than in other developing countries,” elucidates Muhammad Usman Malik, Chief Operating Officer at the Punjab Transport Company.

“From the outset, Airlift and Swvl were embroiled in a struggle for survival against these modes,” he continues.

“In 2019, we surmised that the perseat cost of a coaster operated by Airlift and Swvl was approximately Rs 250, while they were charging a mere Rs 20 per seat, Malik expounds. “They were confronted with the daunting challenge of attracting as many riders as possible whilst simultaneously striving to turn a profit. As their ridership swelled, so did their subsidies and revenue deficits. When they augmented their fares, passengers who had migrated from the aforementioned other modes of transportation reverted to their previous choices. Ultimately, the two had expended a considerable amount of money without achieving the volume of riders they desired,” Malik reflects.

So, what makes BusCaro any different to these two former titans?

Have any lessons been learnt?

As a user, it’s identical to Airlift and Swvl when it comes to booking a ride and getting on. In terms of the operating model, “We rent the buses at a certain price which comes with the bus and the driver. We pay a fixed amount for that and then we pay a variable amount for fuel depending on route and kilometres travelled,” explains Maha Shahzad, Founder of BusCaro.

If it’s like its predecessors for the customers, and it’s like its predecessors in terms of operations. How is it any different?

“We’re a contribution margin positive business. We are profitable on an EBITDA level today in two out of three cities, and those are just the facts,” Maha adds. This makes no sense. Particularly, because Swvl never became EBITDA positive in Pakistan. It did in some of the countries it operated in, but not in Pakistan. How is this possible then?

“I don’t subsidise. I charge what the price is,” states Shahzad. “At that price, I’m half the price of a rickshaw. I’m a fourth of the price of ride-hailing. A bike still remains a cheaper option than me. You can take a bike if you want. If you have the option of a public bus, then go ahead. This is what my price is, this is the correct price in the market, and that’s what I charge,” Shahzad expounds.

This is where we have BusCaro’s eureka moment. It’s just that we might need to perform some linguistic gymnastics to unearth said eureka moment.

Shedding the marketing

“I’m not competing with public buses. If somebody wants this particular service, like people choose to take a rickshaw despite there being public buses or people choose to take a car or people choose to use ride hailing or people choose to use bike hailing. Similarly, if people want to use bus hailing which is what I do then that’s a service that we’re prodiving,” Shahzad continues.

“I compete more with say InDrive, and Careem today than I do with a public bus in terms of customer profiles,” Shahzad elaborates. And therein lies everything.

BusCaro just has a different understanding of the word transit.

“They’re a mobility company, not necessarily a transit company,” states Faizaan Qayyum, Doctoral student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign where he also teaches urban planning and development.

“The Metro Bus is transit. Is Uber public transit? Is InDrive public transit? If I was to take a rickshaw from one place to another on my own with no other passengers, would it be classified as mass transit? These are privatised modes of transportation that get people from one place to another. BusCaro scales up in terms of the passengers it can accommodate. These riders are, however, from a specific socio-economic group,” Qayyum adds.

Now that’s not bad at all. If anything it allows BusCaro to avoid the race to the bottom which the aforementioned Airlift and

Swvl so happily partook in. This is important, because public transit has fundamentally different economics to any of these companies.

Avoiding the slippery slope of public transit economics

“Governments, worldwide, offer subsidised public transport. One cannot simply consider the direct benefits of public transport, or the cost incurred by the government. Public transport is measured in terms of the benefits that the economy as a whole accrues because of it,” asserts Malik. So, the competition is something that’s not designed to make a profit. And it is competition if you come at it. There are no two doubts about that.

“Public and private transport services compete with one another wherever both are available. It is only where one of the two is absent that they complement each other,” Malik adds.Whilst Malik’s statements may seem rudimentary now, this is exactly what Airlift and Swvl did. Why might they have done so?

“Opportunities and gaps also emerge when there are disruptions in the sector, such as when fuel prices skyrocket. That’s when the private sector intervenes to meet additional demand if the public sector is unable to do so. However, the discrepancy between the cost of operating public transport and the revenue it generates is not sustainable for private companies in the long term,” Qayyum expounds. There’s also the case of Swvl and Airlift having the money to burn in this endeavour.

“In the past, there was an abundance of capital flowing into Pakistan, and the emphasis was on growth for its own sake,” states Kalsoom Lakhani, Co-Founder and General Partner at i2i Ventures. “Airlift and Swvl emerged in this environment, which enabled them to raise substantial funds. However, when that funding dried up, it had a profound impact on those companies because they were unable to generate any unit economies. Airlift, at least, had the foresight to pivot away,” Lakhani adds.

Let’s catch up now. BusCaro has the marketing of Airlift, and Swvl. It has the same operational model as them. The target market, however, is different. So, what’s the play?

Is there even a market for BusCaro?

“The state cannot provide a route from my particular doorstep to my office. It cannot make an individualised route for me. It can never cater to individualised service provision irrespective of how efficient, transparent or effective a State is,” explains Qayyum.

“At the end of the day, you will have stops as part of any transit network that you create. Getting to the stop and going to my destination from the stop is what we call lastmile connectivity. The best of transit systems fail when it comes to last-mile connectivity, and this is where the private sector steps in,” he adds. So we have a reason for BusCaro to exist, but what about the customer base?

“Upper income groups are never going to shift to collectivised modes of transportation. They’re accustomed to their cars and they will stick to them. Lower income groups in contrast cannot afford collectivised modes of transportation such as these. In a situation where a Qingqi costs Rs 20, and another costs Rs 15, they will go for the latter. Their finances are that limited and they are that price sensitive,” explains Malik.

He adds that the ideal market for collectivised transport are middle-income groups. “Those that e.g. have motorcycles or their car usage is limited due to any factor,” explains Malik.

According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (2018-19) by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), a staggering 54% of Pakistani households possess motorcycles, while a mere 6% own cars.

Taking into account the potential overlap between these two groups, it can be in- ferred that approximately half of all Pakistani households lack any form of motor vehicle. This presents a lucrative opportunity for BusCaro, provided it maintains fair pricing and refrains from engaging in the cut-throat competition that has plagued its predecessors.

The same PBS survey sheds light on another intriguing fact: the average Pakistani household comprises 6.24 members, significantly reducing per capita vehicle ownership. Even within households that do own vehicles, particularly cars, access is often limited.

As Qayyum elucidates, “It’s not uncommon for car-owning families to possess just a single vehicle. Women in such households frequently have restricted access to cars and must rely on male family members to chauffeur them to their desired destination.”

But what about individuals who own a car and have unfettered access to it? Qayyum ponders the challenge of convenience: “Take the Mehran for example; it travels 17 km per litre. It’s affordable and offers protection from the scorching heat. You have the freedom to depart and return at your leisure and can even run errands en route. Why would anyone opt to pay more for a bus ride when they could simply drive their car? Why pay the same amount or even more when you have the luxury of your own vehicle?”

Nonetheless, there remains a possibility that customers who own cars and have ready access to them may choose to forego their personal vehicles. In such instances, they still have alternatives such as Careem and InDrive. What’s to say they don’t make a grab for the market?

The Careem, and InDrive equation “T

here’s a venn diagram of users. BusCaro’s power users might not be someone that uses Careem and/or InDrive, and vice versa. I do think that at least for their early adopters, they’re not competing for the same kind of user,” states Lakhani

Going just to the corner of the street in the sweltering heat of July and August is enough to sap an individual’s energy. Even if BusCaro were to collect its passengers from the corner of the street, their challenge will be to entice their passengers to walk there whilst alternatives exis

Doctoral student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

However, this does not imply that users will be bereft of choice when they reach for their phones. “Going just to the corner of the street in the sweltering heat of July and August is enough to sap an individual’s energy. Even if BusCaro were to collect its passengers from the corner of the street, their challenge will be to entice their passengers to walk there whilst alternatives exist,” Qayyum expounds.

“It ultimately boils down to what holds greater importance for the user, particularly in light of the current environment where the cost of living is escalating: “It’s a question of walking to a stop versus being chauffeured directly to your doorstep. It’s a balancing act between convenience and cost,” says Lakhani

My understanding is that for their current ridership price trumps convenience. Even though it’s undeniably hot and necessitates walking and all of that, such inconveniences diminish in significance when price sensitivity escalates. We witnessed with Swvl and Airlift how customers flocked to more affordable options. They operated at a time when the economy was better. Presently, everyone is considerably more price sensitive and I believe they’re capitalising on that space right now,”.

What would transpire if InDrive and Careem were to engage in a price war to protect or expand their market share? “Price wars result in discounts. We’ve witnessed this phenomenon in almost every sector that has become fiercely competitive. The B2B e-commerce space in Pakistan exemplifies this trend, where companies raced to the bottom in terms of discounts,” Lakhani elucidates.

“In the current environment, any highburn play that necessitates raising substantial funds and is heavily discount-oriented would raise red flags for investors,” Lakhani muses However, Qayyum believes that it might be feasible: “In the short run, investors can afford to do strange things,”.

Lakhani adds that “growth for growth’s sake was the norm because there was an influx of capital into Pakistan. Companies like Airlift and Swvl were able to raise significant amounts of money. But when that money dried up, particularly in the case of Swvl, it rocked those companies because they weren’t able to produce any positive unit economics,”.

“There is now a greater realisation among international investors that they must exercise greater prudence when conducting due diligence. There’s a focus on how they manage their investments, where governance is, and so forth. There is more importance on many of the considerations that were thrown to the wayside in 2021 and previously,”Lakhani continues.

Third times the charm?

So, we have a company that has all the features of two companies that succeeded in some capacity previously but with positive unit economics this time around. All good then? Perhaps. Is there anything that can go wrong? Lots. We’ve discussed quite a bit already. However, is there anything that can particularly go wrong? Yes. What if BusCaro’s prudence is temporary?

Diamond hands or momentary prudence?

“Consider this: when a business flourishes in times of economic prosperity, capital is abundant. With investors eagerly pouring money into burgeoning enterprises, the expectation is one of hyper growth – a common occurrence during a boom,” states Shahzad.

“However, I find myself in the unenviable position of building during a recession. As such, I am subjected to scrutiny regarding unit economics and profitability, rather than being lauded for exponential growth,” Shahzad adds.

Lakhani laments: “In the current climate, it seems as though everyone is cowering with their tail between their legs. Retrospective conversations abound, with individuals bemoaning past actions and decisions. While I would like to believe that this will result in greater prudence and caution moving forward, experience has taught me otherwise.”

“I haven’t been an investor long enough, but history has shown that hype cycles tend to recur every few years. I see no reason why this trend should change in the future. Perhaps this warrants a broader discussion on the viability of venture capital as an all-ornothing play?” muses Lakhani.

The question then becomes, is BusCaro going to change when the good times come? As it stands, it’s on the precipice of doing what Airlift, and Swvl could not. Albeit, at a significantly lower scale but in a profitable manner. Now, is this a temporary bout or something concrete? We’ll have to wait for the interest rates to truly put BusCaro to the test, because the only thing that ruins a good idea is the prospect of chasing a better one. n

By Babar Nizami, Mariam Umar & @2paisay

The economy has never been this bad; the cost of borrowing money has never been this prohibitive; and businesses have never laid off workers and closed down plants at this scale before.

And yet, one of Pakistan’s largest commercial banks, United Bank Limited (UBL), was able to make an astounding 28% additional loans to businesses towards the end of 2022. This was only a few months ago, and at that time UBL was not the only bank lending money like there was no tomorrow. In fact, total outstanding loans by commercial banks increased rapidly by a massive Rs 820 billion in December 2022 alone. This is the highest monthly increase ever recorded in the combined loan portfolio of the Pakistani banking industry. And that is not just in absolute, but also in percentage terms.

This obviously begs the question: who were these businesses that were borrowing so much money, and that too in such turbulent times? What makes all of this even more suspicious is that the specific banks leading this sudden spurt in lending have long been famous for being averse to the concept of lending to the private sector. Something is clearly amiss here.

Could it be that these banks may have cooked their books by making bogus loans? And if so, how did the most regulated sector in the country get away with it? And perhaps even more importantly, what could have prompted the banks to undertake such a risky mission in the first place?

To answer these questions and to understand what really happened, we need to go back to December 2021 to a scene in Dunya TV’s studio where anchorperson Kamran Khan was interviewing the then finance minister, Shaukat Tarin. But first, some basic background of how banks work.

Advances vs Investments (feel free to skip if you know how banks work)

The first thing you might have heard about how banks run their business is that they are essentially intermediaries. They get money from people who have excess money (depositors) and then channel it to those who need it (borrowers). Banks make a profit by charging a spread between the interest rates they pay on their deposits and the interest rates they charge on their loans. For the latter, banks have two options.

Firstly, they can lend to the private sector, which includes businesses, to finance new machinery, raw materials etc., and individual consumers, for automobile financing, credit cards etc.. This lending to the private sector is called ‘advances’ in banking parlance.

The second option for the banks is to lend to the government. We know that each year, without fail, the Government of Pakistan spends more than it earns, and the shortfall arising out of this, it finances through borrowing. The government does most of this borrowing from Pakistani commercial banks, by selling government bonds to them. These bonds are essentially pieces of paper (or digital records) stating the amount borrowed by the government, the interest rate the government will pay to the bondholder, and the date at which the borrowed amount has to be repaid to the bank. This lending to the Government of Pakistan is what in banking jargon is called ‘investments’.

All banks use a mix of both advances and investments to deploy their funds profitably. The problem is that some of Pakistan’s largest banks (remember UBL in the intro?) are significantly more inclined to make investments (lend to the government), than to make advances (lend to the private sector).

This is a problem because commercial bank’s primary role in the economy is to channelise funds to private businesses. And this is where

Shaukat Tarin comes in.

Additional tax and the Koondathreat

In April 2021, Shaukat Tarin once again donned the mantle of finance minister. Up until his appointment, nobody was really concerned about large commercial banks lending more to the government than the private sector. Tarin, a banker and by now a legend in Pakistani finance, was a strong believer that banks should be making most of their money by lending to both the big and small businesses, as well as to individual consumers.

That he felt very strongly about this was well known amongst the bankers. In fact, Tarin, during his stint at Citibank, had practically invented consumer finance in the country, introducing credit cards and personal loans and vastly expanding the scope of mortgage lending and auto lending in Pakistan. So the banks might just have expected what came next.

In Sep 2021, Tarin decided to penalise banks that were not lending enough to the private sector. He did this by imposing an additional tax on banks that by the end of the year would not have made their total outstanding advances (read loans to the private sector) at least equal to 50% of their deposits figure. More specifically the metric they used to levy this additional tax was the advance-to-deposit ratio (ADR) which measures lending as a portion of deposits.

The idea was simple, Covid-19 was subsiding, inflation was still low and Tarin thought it was time to kickstart the economy. At worst, the government would end up earning a higher tax revenue from banks, and at best banks would start lending more and through that Tarin could deliver growth.

However, while Tarin may have been approaching this from the vantage point of a banker, he was still the finance minister of Pakistan. His ministry still had to actively borrow from the banks to finance the government’s perpetual deficit. In November and December of the same year, the finance ministry asked the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) to conduct an auction of new government bonds and try to sell these to the banks at the lowest possible interest rate.

All of the major banks submitted their bids for the government bonds and it very quickly became apparent that they were all offering their money at an interest rate that was much higher than usual.

The government and the SBP were clearly upset. They accused the banking industry of banding together and acting greedy. The banks said that they were expecting inflation to go up, and thus interest rates to follow suit as well. It only made sense for them to lend to the government at higher than prevailing interest rates they retorted. The banks argued that this was not greed but good judgement as otherwise they could get stuck with bonds which offer lower interest rates. Another argument they presented was that it was logical that banks that had a low ADR would want to be compensated through higher interest rates for the higher tax rate that would be applied on them by the government.

This is when the term Koonda went viral. In Dec 2021, during a live program with Dunya TV’s anchor Kamran Khan, Tarin threatened banks regarding their high bids in the government bond auctions, by saying that if banks do not start behaving he will very easily deploy tools that will ruin the banks (in ka koonda ho jaye ga).

Despite the threat of severe action, banks nonchalantly continued as normal, even pushing their bids further up. To be fair, expectations of a higher future inflation and in turn higher interest rates had set in by this time. But that still does not explain as to what gave banks the confidence to look both the government and the SBP in the eye.

Banks smell blood

The government previously had the option to borrow either from the banks or borrow directly from the SBP. The SBP could create new money to buy government bonds at low interest rates whenever it felt that banks were not offering favourable interest rates on government bond auctions. This creation of new money would obviously have been inflationary, but it was an option nevertheless, and one that was used quite often. But as per an IMF condition, under the amendment made in the SBP law, the government was recently barred from borrowing from the central bank. With the government unable to borrow from its own banker, they had to turn to the commercial banks to keep the water running in the taps.

The commercial banks had caught on. They could smell the blood and felt they had the upper hand as they had essentially become the only lenders to the government.

Seeing that banks, despite the threat, were adamant on demanding higher than usual interest rates from the government, the SBP was forced into a work around. It started creating new money, but this time it was lending at low rates to the banks, which in turn would invest this cheap money in the government bonds after keeping a small spread. This was similar to when before the amendment in the SBP law, SBP would invest directly in government bonds, except this time banks were making a small spread in the process, that too without using any of their own funds.

The banks were obviously very happy as under the new arrangement they could continue to make profitable investments in government bonds and that too without having to worry about the negative impact of making too much of an investment on the bank’s ADR. You see ADR is advances divided by deposits. Now banks were making most of their investments using the money they borrowed from SBP, hence it was no more an either or choice for the banks between making advances or making investments. They could now continue to make investments, using SBP money, and make loans from the deposits if they wished to.

This was, in essence, a four month long chess match. The government had made an aggressive opening play and the banks had responded by sticking to their guns and taking advantage of the fundamental weaknesses in the federal government.

The government bites back

By the beginning of 2022 the banks were winning and the government was on the back foot. Now, the government deals with commercial banks in an individual capacity. But the overwhelming response from the banking industry was very similar. Bruised and bloodied by this united front that insisted on higher interest rates, the government decided it had had just about enough.

In January 2022 the government, through the Competition Commision of Pakistan initiated a hostile inquiry into the alleged collusive practices by some banks in the government bond auctions. The allegation was that banks were not competing with each other while bidding for government bonds, and were instead working together so that all the banks that were bidding would make a killing. Banks presidents and their treasury staff (the ones that make bids in government bond auctions) were obvioulsly not amused.

Let’s recap. Banks were comfortable lending to the government and earning interest income rather than lending to the private sector, the former being more secure and easily executed. Tarin, the finance minister at the time wasn’t having any of it and in a bid to force banks to lend more rather than just buy government-backed securities, placed an additional tax on any bank with an ADR lower than 50%. Banks doubled down, demanding an even higher return on government securities to cover the cost of the new tax. Tarin’s finance ministry, as a result, might have made more money in taxes from these banks, but it would have probably ended up paying the same money or more back to the banks in the form of additional interest rates on government bonds. To bring the government’s cost of borrowing down, SBP starts lending cheap money to the banks, which they can lend further to the government. But by now the relationship between the government/SBP and the banks had clearly become sour.

Miftah doubles down

In April 2022 Tarin and his boss, Prime minister Imran Khan were removed from office through a vote of no confidence, and Miftah Ismail became the new finance minister of Pakistan. Miftah and the new governor at SBP, who was in Tarin’s tenure the deputy governor at SBP, also seemed convinced that the banks were being too greedy, making more than they should, and must be punished.

Miftah increased the ADR tax. Banks by now had had enough of trying to fight this tax by increasing the interest rates they demanded on government bonds, as there were too many dressing down sessions at the SBP, and other inquiries that they had to go through.

Also, not every bank had a low ADR issue and therefore no additional tax cost to cover by making higher interest rate bids (demand) in auctions. So the banks with above 50% ADR would have most likely outbid the banks with low ADRs had the latter asked for higher interest rates.

Simultaneously, the SBP was continuously injecting new money into the banking system to lend further to the government. Demanding a higher spread on money that SBP, which is also the banking regulator, had lent cheaply, would have been a bit too much to digest for the SBP. So, these low ADR banks had two choices now, they could continue to maintain low ADRs and as a result pay a much higher tax to the government. Or they could finally start lending to the private sector, improve their ADRs and avoid the extra tax. And lending they did. Well, sort of.

Banks start to lend. Or do they?

As mentioned earlier, it’s not like all commercial banks had a low ADR issue going into the year end. Some Pakistani banks do actually believe in lending, as opposed to prioritising investing in government bonds. Take Faysal Bank which already had an ADR of 67% at the end of Sep 2022, three months prior to the year end. In fact the overall industry ADR stood at 49%, only one percentage point below the 50% ADR required to avoid the extra tax.

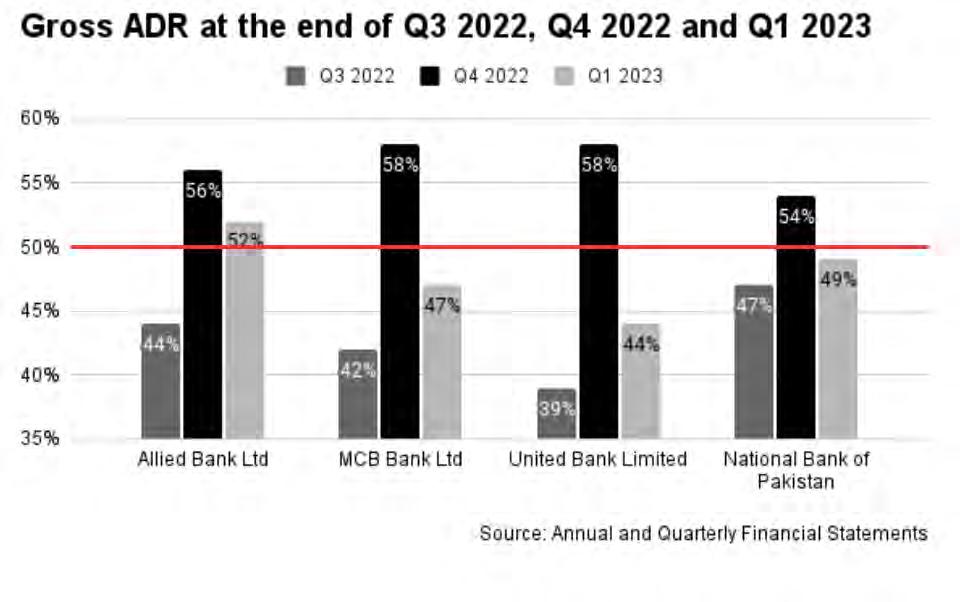

This means the banking industry was, on average, already lending almost half of its deposits. It is only when one digs deeper into data of individual banks that one realises that four particular banks stand out in all of this: UBL, MCB Bank, Allied Bank and National Bank of Pakistan (NBP). All these banks have three things in common: 1) they are all big banks, 2) all of them had low ADR at the end of Sep 2022. And 3) all of these banks started lending towards the end of 2022 and managed to increase their ADR beyond 50%. This meant that at year end, barring one small bank, there was not a single bank left that had to pay the additional tax applied on banks with low ADR.

To understand the scale of this lending spurt, let’s start from the top. UBL had an ADR of only 39% at the end of Sep 2022, but when it disclosed its year end financials, the ratio had miraculously jumped to 58%; MCB had an ADR of 42%, which increased to 58% in the same three months; Allied Bank had an ADR of

44% which increased to 56% and NBP had an ADR of 47% which increased to 54%. Not surprisingly, the ADR of all four banks dropped considerably soon after, so much so that the ADR of three out of the four banks again dropped below the 50% threshold. This made the suspicion of possible year end window dressing even stronger. (see chart below).

But to whom and for what? (do not skip anything now)

Let’s get one thing out of the way first. It is an open secret that every year Pakistani banks indulge in a bit of window dressing to make their year end financials look better than they actually are. And it’s a pretty simple process. Imagine it is the last working week before the year ends and you have to make a big payment through a pay order for a house you recently bought. Two things can happen: either you will get a call from your branch manager requesting to delay the payment till 1st of January, or they may just ask their subordinate responsible for making the pay order to slow down the process. You know where they tell you “system down ho gaya hai”.

Similarly, on the advances side banks’ credit managers, call up their clients at year end and request them to borrow any underutilised lending limits, even if this is to be done for a few days. This makes the banks look slightly better in terms of their lending habits (better ADR), than they actually are.

So why do this story? Because this time was very different. In fact, the sheer scale, the reasoning for doing it, and the process through which it was done make this window dressing exercise way different from anything we have seen in the past.

So this is how they did it. We know that ADR is advances divided by deposits. Before coming to the advances (don’t worry, we tackle those in detail in a minute) let’s get the deposits out of the way.

Even though it is intuitive to assume that when banks were asked to improve their ADR, the government wanted the banks to lend more. But in theory banks could also increase their ADR if they could somehow reduce the denominator, i.e the deposits. Banks proved that they are not a one trick pony, as they increased both advances and reduced deposits simultaneously to achieve the above 50% ADR target. Hence for the first time in the last twenty one years (prior data is not available), in the last month of a financial year, banks opted to decrease their deposits, causing the number to drop by Rs 265 billion in Dec 2022. This break from the traditional pattern where banks would artificially hold onto deposits to meet performance goals and inflate their deposits in the month of December, only to release them in January was a first.

There was a complete lack of the usual year-end efforts to keep deposits up, no relationship managers (RMs) making phone calls and visits to clients to persuade them to not make any major withdrawals or to move some money from other bank accounts into theirs. None of that.

But this intentional reduction in the denominator part of the ratio is not enough to go above the crucial 50% ADR number. This is where the advances come in and where the real gimmickry is visible. As mentioned earlier, there was an unprecedented astronomical increase in advances in Dec 2022, Rs 820 billion worth. That it came in an economic climate where businesses are having a hard time keeping their heads above water makes the number all the more intriguing.

Let’s break down the Rs 820 billion figure a bit to understand who borrowed it and why.

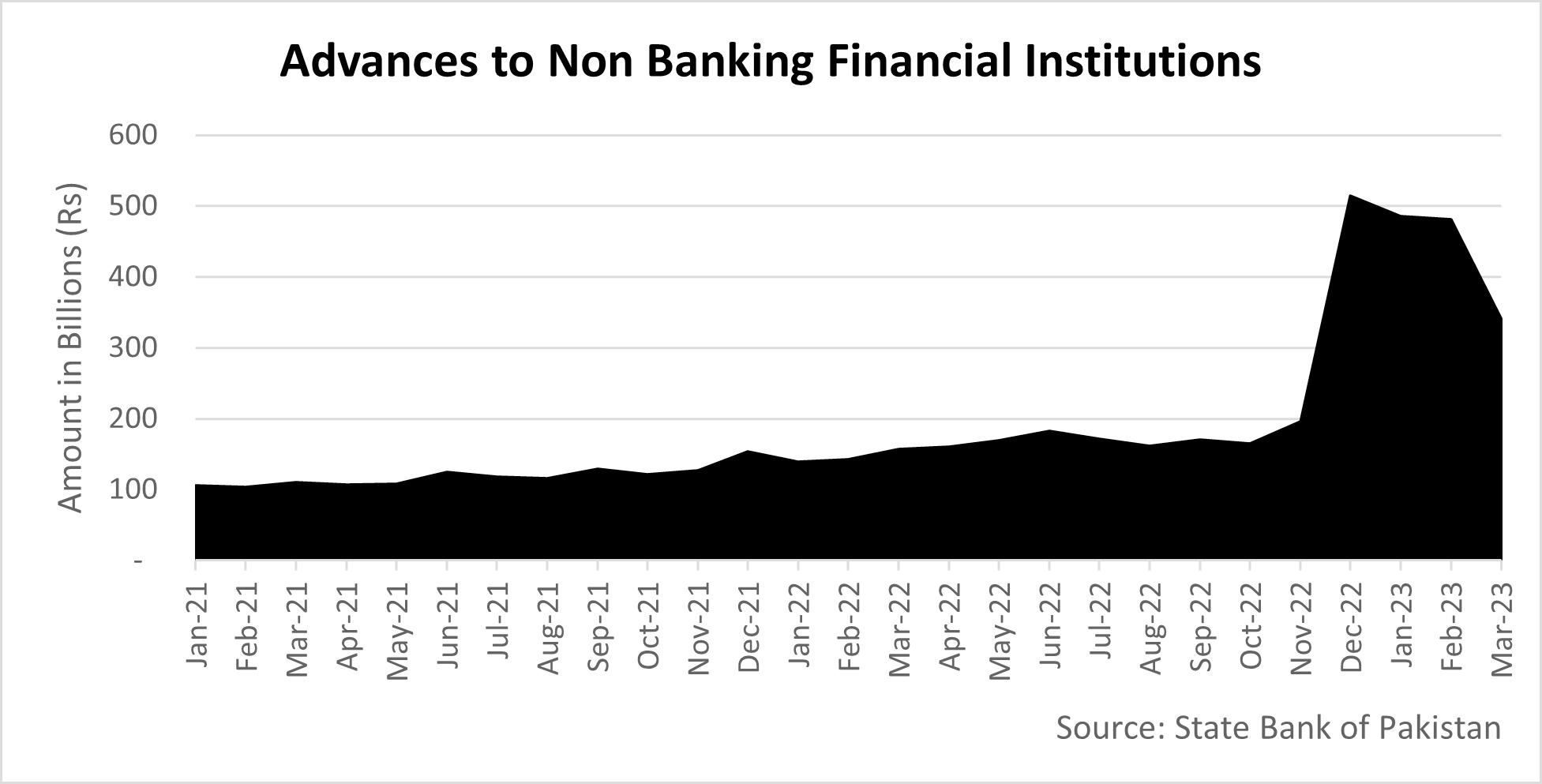

Financial institutions other than commercial banks

This is where a major chunk of the increase in advances was made, to be more precise an additional Rs 318 billion was lent to Non Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs) in the month of Dec 2022 only. This translated into an astounding 162% increase in advances to this sector, and what stood out was that never before had the combined advances to this sector crossed Rs 200 billion, and here just the increase in a single month was much more than that. But who are these NBFIs and what did they do with money? You see, commercial banks are not the only businesses whose primary activity is dealing with money and other monetary assets. In fact we also have many other financial institutions that, barring few differences, work very similar to the commercial banks. Take the example of Microfinance banks. Like commercial banks they also take deposits, make advances and yes, invest in government bonds. Hence, the loophole to avoid the ADR tax was right there. Commercial banks could easily make loans to microfinance banks and ask the microfinance banks to invest those funds on behalf of the commercial banks in government securities. The commercial banks and the microfinance banks could then share the profits. This way the loans made to the microfinance bank would show up as lending to the private sector (advances) in the commercial bank’s financial statements and inturn increase the commercial bank’s ADR. And this way the microfinance bank’s ADR doesn’t get negatively affected either, because this transaction neither relates to the deposits, nor the advances figure of the microfinance bank. And even if it did, the ADR related taxation was only levied on commercial banks.

Editor’s note: We have not explained the specifics of how these transactions are being structured between the banks, microfinance banks and in some cases the asset management companies of these commercial banks in this piece. However, if this interests you, you can read the fascinating piece titled: “Grow your company size by 3 to 6 times in just months. At least two Pakistani companies have done this & you can too. Here is how”, at the end of this story.

Of these, the financials of U Microfinance Bank (Ubank) stand out. Its borrowings increased from Rs 37 billion in 2021 to Rs 116 billion in 2022, a 3 times increase in just one year. And what did it do with this additional Rs 79 billion? You guessed it! It invested this, and then some in government bonds with a total increase in investment of Rs 91 billion in 2022.

Of late, Microfinance banks in general have been struggling financially. So the fact that UBank was able to borrow Rs 40 billion from Allied Bank Limited, MCB and Askari Bank seems strange. Why have banks chosen to lend to UBank, especially given the wider struggles within the microfinance banking industry?

Kabeer Naqvi, CEO Ubank, while speaking to Profit explains that since the regulator allows microfinance banks to make investments, they invest in government securities and will continue to do so and expand to become the first microfinance bank in Pakistan with an active treasury and for this have created strategic alliances with multiple banks and to create a win-win situation for both to facilitate this.

What Kabeer is essentially suggesting is that the practice of borrowing from commercial banks to invest in government bonds is normal, and they have been at it for a few years. He is right, UBank has been growing its investments and borrowings for quite a few years now. The fact that this year the increase, especially in absolute numbers, was much more leads us to believe that banks, at least some of them, were too keen to lend to UBank to avoid the ADR tax, but since there is no way we can know the intent of the lender or the borrower, unless they themselves confirm, we can leave it here for our readers to make their own conclusions.

But there is one player who has unequivocally confirmed what we are suggesting.

Within the NBFI space, we also have a set of financial companies that are called Development Finance Institutes (DFI). These are essentially companies owned jointly by the Government of Pakistan with another foreign government. One such DFI, disclosed to Profit that 2-3 banks approached them and offered them a loan at very low rates towards the end of the year. The DFI in question confirmed that the interest rate on these loans was even lower than even the rate at which SBP lends to banks. This rate charged by the SBP, as also explained earlier in the story, is the cheapest possible loan in the financial industry. What did the DFI do with the loan, it obviously bought government bonds with and made a quick buck.

The DFI disclosed that these discounted loans were extended by UBL and Allied Bank towards the end of the year, and since these loans were very short term in nature, these have already been paid back. This is a smoking gun! There is simply no possible explanation for UBL and Allied Bank to be making loans at a loss, (borrowing forming from SBP and then lending to a DFI at a rate even lower than the rate being charged by SBP), other than that they were doing this to artificially improve their ADR, and avoid the extra taxes associated with a lower than 50% ADR.

Both banks simply did the math: the tax saving from the ADR tax you avoid more than justifies the loss taken on the loan made to the DFI at a loss.

Both UBL and Allied Bank declined to respond to any of our queries that were sent to them over ten days back.

Editor’s note: Profit managed to get confirmation from one borrower, but the regulators, with access to detailed data, can ascertain the scale of this exercise and also find out which other banks were involved in it.

The rest of it

Apart from DFIs, private sector lending was another important avenue for commercial banks to manage their ADR problem. In fact total advances to the private sector increased by an impressive Rs 450 billion. This, as previously mentioned, was surprising considering the very high interest rate environment and the bad state of business and economy. However, to make a deeper analysis the availability of data in this respect is scarce. The little data that is available is sector wise making it difficult for us to ascertain which particular companies took a route similar to that of NBFIs to cater to the banks. That is how much of this additional lending to private sector businesses was further investment in government bonds by these companies. Just in case you didn’t know, any business or even an individual can invest in government bonds. It’s just that they have to go through their commercial banks who are the only ones allowed to participate in SBP conducted auctions of government bonds. That said, here too are some things that are just too blatant to ignore.

In December 2022 banks extended Rs 65 billion worth of new loans against bank deposits. This means businesses took out loans after giving their own deposits as securities against those loans. If they needed money why didn’t they simply use the money in their own bank accounts instead? This makes little sense at first. Why would any business with money in its bank account borrow against that same money and pay interest for a loan it doesn’t require? Absurd as it may sound, businesses sometimes do borrow against their own bank deposits for various reasons, which are not relevant to this story. But what is relevant is that this lending against bank deposits increased all of a sudden in December 2022 by 16%. That’s a big increase for one month. What makes it further suspicious is that the very next month the extra amount lent had dropped by approximately the same amount.

Directed by our many conversations with various corporate bankers, this year-end borrowing against banks deposits for a few days can be explained by some good old relationship management.

“Hey there SMEs. Do you want better rates from us next fiscal year? Do us this solid now and you got it!’ Hello Corporates. Look, we’ve known each other for a while, been through a lot together, and this is us calling in that favour,” the RMs would go.

And of course, there is the profit making opportunity that Pak Kuwait and UBank availed that these private sector companies could also have benefited from while also making their banks happy. That is, these private sector businesses could have also used these and other loans they took at a relatively low interest rate to make investments in government securities.

Playing the devil’s advocate: Making a case for banks

None of the banks contacted for this story responded to Profit’s queries. However, to understand the decisions being made by the C-level executives and board members at these banks, your correspondent spoke to a number of industry experts and gathered some background information to craft what a hypothetical reply in support of the banks’ actions would look like:

• The Pakistani banking industry is already highly taxed. In 2021, when the seeds for this current situation were sown, the corporate income tax on banks was a steep 35%. That is 6% higher than the 29% figure that is imposed on non banking-businesses. Afterwards the tax rate was further increased to 39%. And then there is also a super tax on banks.

• There is this general perception that banks are greedy. To that I would say, yeah so what? Banks are in the financial sector to make money and there are no two ways about that. So what is wrong with being greedy? If a bank ever gets exploitative that can be managed with regulation but greed is good because it helps the bottom line for our shareholders. If we are in it to make money, why would they choose to do the government favours at the cost of their own bottom lines?

• And then this is the most important part that no one will tell you on record. Yes, we do hop around the government’s drawn lines every now and then. It is called utilising a loophole and there is nothing strictly illegal about it. Generally speaking, the banking sector does use loopholes but usually sticks to the legal route. And in this particular case, forced lending can be bad for the banking system’s stability. The banks have to control who they hand it out to.

ADR tax removed

It was clear that the tax was not working. Banks had found a work around. One thing was for sure. Some of the legacy banks would just not change. And as explained earlier there is a case to be made for this in the Pakistani context. So the government in Feb 2023 removed the ADR related taxation.

However under Miftah, the government did one more thing. It created competition for the banks by also allowing DFI’s to borrow from the SBP. Also within the commercial banks, NBP which is a government owned bank, has become the most active player in government bond auctions. Government bond holdings of all commercial banks increased by Rs 3.3 trillion in 2022, out of which 1.54 trillion was just attributed to NBP.

What now?

So here we stand. We started the story with a small development that took place back in 2021. The government of Pakistan came out swinging against commercial banks for not lending enough money to commercial clients. To make the banks change their ways, the government imposed a tax on banks with an ADR ratio less than 50%. However, the government was still reliant on commercial banks for a lot of their money and asked them to lend money by picking up government bonds.

That’s when the banks bit back. They demanded a much higher interest rate than the government was willing to pay. What followed was a Mexican standoff that eventually ended with the banks doing some clever book-keeping to alter their numbers and the tax being removed. So what was the point of this entire episode?

There are a few interpretations to this.

The first is that the government wanted to punish the banks and managed to impose a tax on banks. And while the tax has been removed, the government has now found an alternate route to borrow money through DFIs instead of commercial banks. At the same time, while the ADR tax has finished, the government has since imposed a super tax that cannot be manipulated.

Then there is the other interpretation. That it was not so much the government putting up a fight and the banks reacting as it was the banks stepping back from doing business with the government. You see, buying government bonds is considered a safe investment since the government is not really supposed to go broke. However, over the past few months along with talk of sovereign default there has also been discussion that Pakistan might be headed towards domestic debt restructuring. Essentially, if the government is unable to pay back the banks the banks will have to move the repayments forward and take a loss on their books. As a result, the banks decided to ask for a higher interest rate on bonds since the government was now a risky investment. Take Allied Bank for example. One of the bigger banks in Pakistan, they actually stepped away from their primary dealer status to avoid having to participate in the auction for govern- ment bonds.

As of now, everything is back to normal. Deposits are being channelled to the government, if not directly then indirectly. SBP is lending to the government and mostly through entities with a large government stake. Government has imposed additional taxes on bank’s incomes, but without a link to any other metric that can be manipulated. Seems everyone has learnt their lessons and to some extent everyone is back to being happy again.

Disclaimer: Some concepts and definitions have been simplified for purposes of brevity and clarity.

By @2paisay & Mariam Umar

Step 1: [This step is only applicable to Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) and other non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs) that can accept deposits,so move directly to step 2 if you are a normal business]

Get commercial banks and money market funds (mutual fund companies that invest most of their money in government bonds, but also keep some of it in cash) to either deposit their cash holdings or place money (Letter of Placement, Certificates of Deposits) with you.

Step 2: Use the funds received in Step 1 (in case of NBFI/DFI) or any excess funds that are already available with the company (in case of a non-financial corporate) to purchase units of money market funds or short-term government securities i.e. T Bills. You could also buy long term government securities i.e., PIBs s. Just make sure that PIBs are floaters, i.e if interest rates increase, your return should also increase.

Step 3: Now pledge your units of money market fund or the government securities with commercial banks to borrow money against these. Banks will happily lend you at very low rates as this lending is secured by the two of the most liquid collaterals in the country i.e.

Highly marketable and credit risk free Tbills and PIBs issued by Government of Pakistan and Money Market Funds that mainly invest in aforementioned TBills and PIBs. But if you have a DFI license, go to

Step 3b as it offers even cheaper loans.

Step 3b: Use the Government of Pakistan securities to borrow from the SBP directly through a repo (recently made available to DFIs only). The rates offered by SBP for these loans are almost always lower than the rates charged by commercial banks. .

Plan such that the tenor of your borrowings (whether through commercial banks or SBP) is longer than the duration of your investments.

Step 4: Now use this newly borrowed money to buy more government securities (or units of money market funds).

Step 5: Go back to Step 3

Step 1 and Step 2 are there just to kickstart the process. The exponential growth comes from continuously cycling through steps 3 to 5 i.e. buy-pledge-borrow. U Microfinance Bank (Ubank) has been able to double the size of its balance sheet in a year, and it has been successfully doing this for the last few years, while Pak Kuwait Investment Company (Pak-Kuwait), Pakistan’s largest DFI has been able to increase it by 6 fold in around 9 months by just cycling through steps 3 to 5.

On each position, you make a very very small profit. However, if you can build a very large position like UBank or Pak-Kuwait by repeatedly cycling through steps 3 to 5, the size of your profit may become meaningful.

FAQs

Question 1: In light of developments in the US banking sector wherein banks have been collapsing on account of mismatch between assets and liabilities, isn’t this a risky position?

Answer: The US banks took positions in long-dated fixed-rate mortgage securities which can become illiquid or accrue valuation losses in a rising interest rate environment. The strategy we followed in Pakistan involves investing in securities which aren’t affected much in a rising interest rate environment. As interest rates rise (as had been the case for sometime now) you would get higher interest income on your investments because your long term investments carry a floating rate and you can roll over your maturing short term securities into the higher yielding newly issued short term T bills. Thus, unlike the US banks, there is hardly any valuation loss on your asset side and your interest income has actually increased. While on the liability and expense side, your borrowing costs are fixed. Thus, in a rising interest rate environment, this strategy produces a positive return, albeit a very small one.

Question 2: This is a huge increase in balance sheet size. This strategy would have resulted in earth shattering income.

Answer: Unfortunately, that does not appear to be the case. It is hard to tease out the net impact of this strategy for UBank from its financial statement. We can, however, calculate the return to Pak-Kuwait of this strategy. Pak-Kuwait’s total investment in government securities increased from Rs.64 billion to Rs.679 billion from Dec 31, 2021 to Dec 31, 2022. During the same period, Pak-Kuwait was able to increase its net markup income by mere Rs.272 million which translates into a return on average assets of 0.07%. But hey, it is riskfree easy money.

Editor’s note: Both UBank and Pak-Kuwait recently released their first quarter financials for 2023. Based on extensive interviews, a deep dive into both UBank’s and Pak-Kuwait’s strategy and performance to follow in the following issues of Profit.

Question 3: Is there a limit to this strategy?

Answer: To date we have not seen a ceiling. Pak-Kuwait successfully grew its assets 6 fold purely based on the aforementioned strategy in 9 months (total assets grew from Rs 137 billion at the end of March 2022 to Rs 798 billion on Dec 31, 2022). UBank doubled its asset size from Rs 104 billion on Dec 31, 2021 to Rs 221 billion on Dec 31, 2022 and its leverage (total assets/net assets) from 15x to 30X in the same period.

Question 4: Is this strategy followed by DFIs and NBFIs in other parts of the world?

Answer: Such strategies are usually part of relative value “long short” strategies adopted by hedge funds wherein they fund their extremely large position in treasuries through repos, while at the same time selling corresponding future contracts and profiting from small differences between yield on cash treasuries and the corresponding futures. Since the cash yield and futures yield move together, the hedge funds can pocket the small yield difference regardless of which way the market moves. Such strategies are affectionately referred to as “picking up pennies in front of a steamroller” as hedge funds have a tendency to blow up when such strategies don’t work as advertised.

In the case of UBank and Pak-Kuwait, there is no corresponding futures contract or short position to hedge their long position. Both are earning pennies based on the yield difference between their borrowing/repo yield and government securities yield.

Question 5: UBank maintains deposits of retail accounts. PakKuwait is using SBP repos which are usually short tenor (around 7 days or less). Isn’t the SBP as a regulator worried about UBank and Pak-Kuwait behaving like hedge funds?

Answer: SBP’s mandate is the financial stability of the system. I cannot claim to understand what SBP is thinking other than what has already been explained in Question 1 above, however, I can assume that despite the fact that leverage of UBank has increased from 15x to 30x based purely on the above strategy, SBP does not deem it to be a systemic risk to the financial system. Pak-Kuwait does not have retail deposit accounts and all its borrowing is against “risk free” government securities which are pledged with SBP. Also Pak-Kuwait, for now, is using longer-term repos to borrow from SBP, that range from 63-70 days.

Question 6: Don’t the auditors or the board of directors or board risk committees find this approach risky?

Answer: The auditors have not highlighted any risk from the aforementioned strategy in the annual accounts. If the board or the risk committee had any concerns, they have been allayed by the management. Otherwise how could UBank have increased its leverage to 30x in a year and Pak-Kuwait increased its asset size by 6 fold in 9 months. The board of directors and risk committees would be fully on board with this strategy.

Question 7: DFIs are allowed to participate in open market operations under SBP DMMD circular 11 of 2022 which allows DFIs to participate in OMOs for liquidity management. Pak-Kuwait is using OMOs to take highly leveraged and speculative positions in Government securities. This isn’t the objective of the circular. Is SBP not aware of it?

Answer: SBP should be fully aware of it. Over the years, repo balances on the SBP balance sheet have been increasing and have become a permanent source of indirect financing, via commercial banks, to the Government of Pakistan. Since the late 2021 and throughout 2022, SBP conducted 63, 70 and 77 day OMOs, not necessarily to inject liquidity in the system, though that is the official line, but to provide cheaper source of money to commercial banks to nudge them to participate in the auction of government securities which otherwise the banks are reluctant to do so fearing rising interest rates. All this to say that SBP should be fully cognizant that participation by Pak-Kuwait in OMO isn’t for liquidity reasons but to be a leverage buyer of government securities, similar to the commercial banks.

Question 8: Why do banks lend against pledged Money Market Fund (MMF) units?

Answer: The banks own the Asset Management Companies (AMC’s) that manage the MMFs. By lending against the MMF units, banks help their AMCs increase their Asset Under Management (AUM). This enables AMCs to earn higher income as AMCs charge management fees based on AUMs. From a risk perspective, the MMFs invest in government securities so banks are essentially lending against government securities thus taking minimal risk.

Question 9: For this to make sense for NBFIs and DFIs, banks should be lending at a slightly lower rate than the yield on government securities. Why are banks leaving money on the table and not investing directly in government securities?

Answer: In September 2021, the government decided to impose an incremental tax on banks whose advances-to-deposit ratio (ADR) would fall below particular benchmarks apparently to encourage the banks to lend to the private sector. However, the banks it seems found a way out of this conundrum i.e., window dress their investments by lending to NBFIs etc., which then purchase government securities with this money and pledge those securities to the same banks. The banks may be leaving a few bps (one bps is 1/100 of 1%) on the table but saving a few percentage points on the tax. It is funny how egregious some of the banks have been in this i.e., first lending/depositing money to/with the borrower to invest in MMFs, and then lending more money to the borrower against the very MMFs to buy government securities, and so on. In the bank and SBP reporting, this appears as advances/lending whereas effectively it is indirect investment in government securities.

Editor’s Note: Two big banks, namely UBL and ABL, were specifically asked to explain their intentions behind lending to NBFI’s instead of investing directly in government securities. No response was received till the filing of this report.

Market sentiments and the business community’s confidence is almost entirely shot. But how are they preparing for the worst?

By Abdullah Niazi and Daniyal Ahmad

There is a mistake that actors preparing to play Julias Caesar in Shakespeare’s seminal historical play often make. In the scene where Caesar is stabbed on the floor of the senate, they scream or shout out in agony. But any director or acting coach worth their salt will tell the actor that a person getting stabbed in the back does not respond with a scream, a shout, or any other such theatrics.

No.

The response is always a gasp. The force of a dagger entering the back completely knocks the wind out of a man. The reaction, thus, is an exhale. In the case of playing Caesar, it is a gasp of the most tragic proportions where the literal life pours out of a once proud and powerful man. The anger, the betrayal, the hopelessness, the helplessness all translate into one agonising release of breath followed by a slow but inevitable slump onto the floor.

Pakistan, and more specifically its economy, is the middle of one such gasp. Over the past week, Profit has been in contact with major industrial players all over Pakistan. Many of them ranted and raved. Others expressed shock and dismay. There were still more that had no reaction other than complete and utter resignation at the road that lies ahead.

All of them agreed on one thing: they have no idea what is going to happen but it will be bad.

Put things in context. Pakistan has for all intents and purposes given up on a deal being struck with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The finance minister, who was responsible for messing up the process in the first place, has publicly said in his latest statement that the country cannot continue to take difficult decisions for the sake of the IMF. He has also claimed that even if the deal falls through Pakistan won’t default.

This last claim is a little difficult to digest. We currently have no money to repay our external debts in the July to December time period. Since a lot of our foreign aid is contingent on the IMF signing an agreement and releasing funds it seems next to impossible. At the same time, the government has just told the fund they will roll back their petrol cross-subsidy plan to secure the deal, indicating very strongly that they know there is no recourse without the fund being on board. It doesn’t help public sentiment that the government has been lying to the public about the state of negotiations with the IMF since February, promising that the deal is “just a few days away” for four months now.

Caught in the midst of all this are the people of Pakistan. Hounded, beleaguered, lied to, angry, and disrupted by the political chaos that has escalated in the country since the arrest of former prime minister Imran Khan, the cost of living crisis and unemployment that could rise out of a default may complete throw Pakistan into chaos and its people into despondency.

Perhaps nothing better captures the despondency than industry sentiments. The confidence of the business community is shot, and while there are many places and people to point fingers towards, the current reality is sobering. The following are a collection of comments and reactions to the ongoing political, economic, and social crisis in Pakistan from major business and industrial leaders and market experts.