20 minute read

CON TENTS

10

10 Uncompetitive and short in supply. The tragic and avoidable undoing of Pakistan’s cotton crop

Advertisement

19

19 Pakistan Railways looks to monetise its assets, but will advertisers bite?

27

27 Futafut – Pakistan’s latest fintech gamble

32 Flipping the script

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Abdullah Niazi

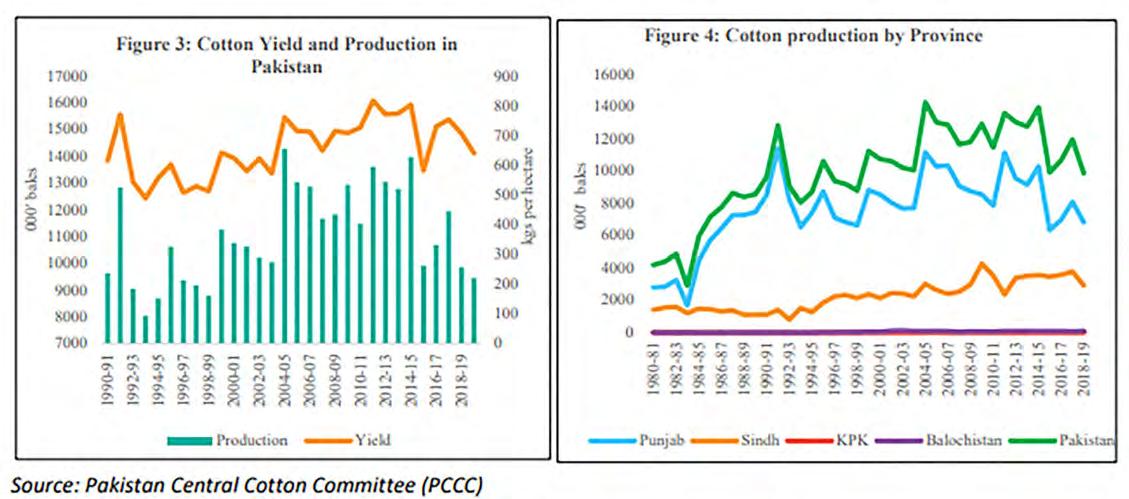

This is the story of how one of Pakistan’s most valuable crops was destroyed in less than 15 years. According to data released by the Pakistan Cotton Growers Association (PCGA) last week, Pakistan’s cotton output has now fallen to its lowest levels in the past 40 years. To those that have been observing the cotton industry for the past few years, the massive dip does not come as a surprise.

Over the past two decades, the cotton crop in Pakistan has fallen out of demand, has become internationally uncompetitive, and output has fallen by a whopping 65% from 14 million bales being produced in 2005 to 4.9 million bales being produced in 2023.

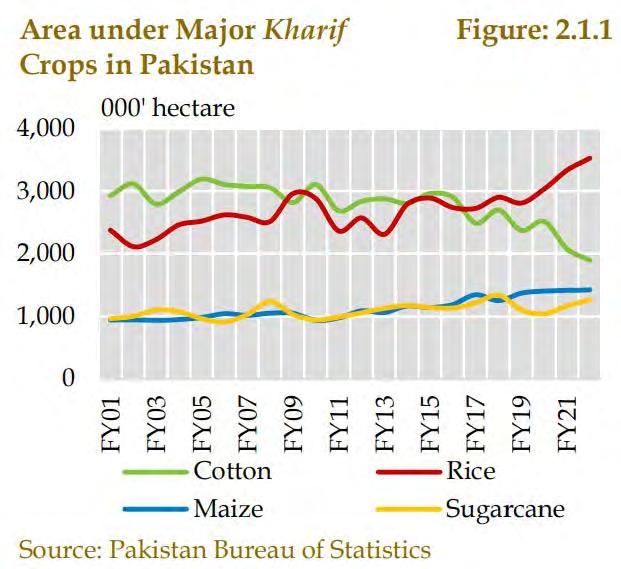

Once the darling of farmers and agriculturalists, the area dedicated to cotton farming has also been shrinking significantly since the late 2000s while competitor countries like Egypt have increased the area they are dedicating to growing cotton. Other than a brief recovery in 2022, when output increased only because of an irregularity of international trade created by the Covid-19 pandemic, cotton has continued to fall out of favour and the results have meant a complete shift in Pakistan’s exports.

The biggest impact other than on farmers has been on Pakistan’s textile industry. In the secondary sector, the cotton-based textile industries have a 21% share in largescale manufacturing and consequently a 2% share in the national GDP. With cotton production falling and area-under-yield shrinking as well, the textile industry has increasingly had to depend on importing cotton. Last year, in some ways, was actually an opportunity to bolster and revive cotton production in the country. The question is whether that opportunity has been squandered or is there still time yet?

Cotton on the ropes

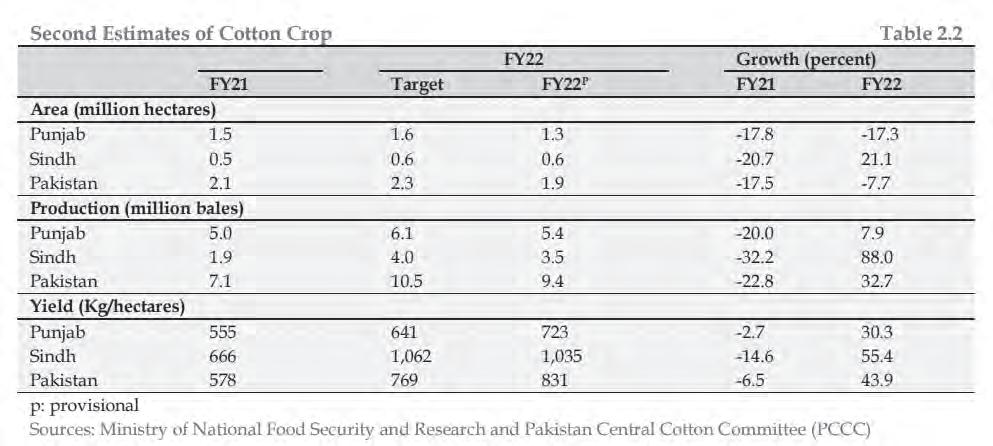

The story of cotton in Pakistan has been that of an opportunity squandered. Between 2005 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2005 to just over 9 million bales in 2020.It further fell to 5.6 million bales in 2021, before making a brief recovery at 7.7 million bales in 2022, and has now fallen to a paltry 4.9 million bales in 2023. This marks an overall decline of 65% in the past 18 years.

The data speaks for itself. Zoom in to cotton production over the past few years and it is a sordid tale. As recently as 2017, Pakistan’s cotton production was high, clocking in at over 10 million bales for the year. The output actually rose by a million bales to 11 million in 2018, before settling again at just over 9 million bales in 2019. The next two years saw a decline. In 2020, only 8 million bales were recorded before a sharp fall to 5.6 million bales in 2021.

{Note: There is no reliable tabulation for how much cotton is produced in the country by government sources. However, the Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association (PCGA) keeps count of how many bales of cotton arrive at ginning factories for processing. That is why the country’s cotton output is calculated in bales rather than by weight. For context, a single bale is 170 kilograms.}

Farmers over the past decade have abandoned cotton in favour of more profitable crops like sugarcane. In 1991, cotton was grown on around 6.6 million acres of land all over Pakistan. It grew to a peak area-under-cultivation level of 7.9 million acres in 2005 but stood at a mere 6.2 million in 2020 showing a serious backwards trend. Changing climatic conditions have made the cotton seed in Pakistan less resistant and more likely to fail — which means growing it has become a bad business decision for a number of agriculturalists.

So why did farmers abandon the cotton crop in droves? Especially at a time when countries like Egypt and Vietnam with whom Pakistan used to compete have only increased the area they grow cotton on? The falling stock of cotton goes back to 2008 — when the energy crisis hit Pakistan and the textile industry was jolted.

Impact on the textile industry

Cotton was a major cash crop in Pakistan until 2008. In fact, in 2005, cotton became one of the only crops in Pakistan for which GMO seeds were introduced. According to a 2021 report of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), raw cotton consumption grew at an annual growth rate of 7% between 1982 and 2008 to reach 15.6 million bales in 2007-08 in Pakistan.

However, between 2007-8 Pakistan was hit by the global recession. The textile industry faced challenges due to high energy costs, rupee depreciation vis-à-vis the US $ and other currencies, and a high cost of doing business. As a result, there was a reduction in the number of textile mills operating in the country from about 450 units in 2009 to 400 units in 2019. This decrease has simultaneously seen the domestic demand for cotton dip in the country.

Farmers and the textile industry, up until the 2008 financial crisis, had been dependent on each other. Farmers would produce the crop without the fear that demand would fall, and the government did not need to announce a support price either. But when mills started shutting down, suddenly there was more cotton and not enough buyers. After a harsh couple of years, farmers also began going back on cotton and its price fell, resulting in production decreasing. As a result, exports were also affected.

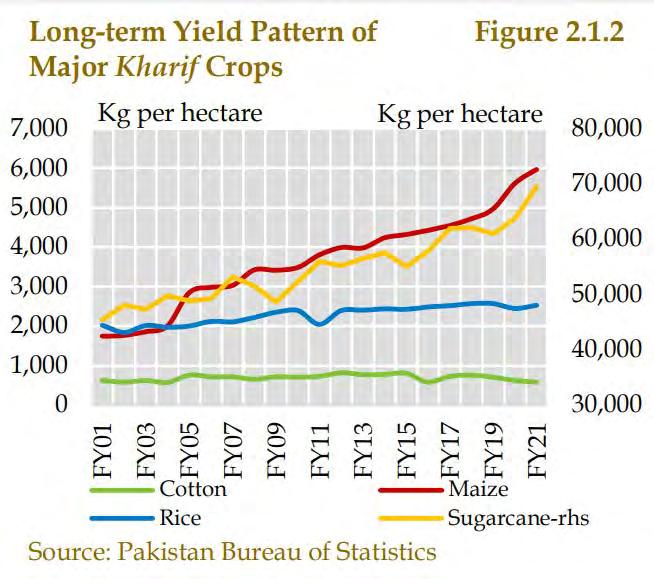

At the same time, since farmers were losing interest in cotton, very little cotton research was done in the country. This meant that other cotton producing countries were able to use the latest seed technology and science to increase their yield while Pakistan fell behind. Here is a sobering statistic. Two decades ago, Pakistan’s cotton was in demand globally. However over those 20 years, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all used better growing techniques to get ahead of Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $25.3 billion in 2020. The explanations behind this are multiple. Pakistan needs to increase not just the amount of cotton it produces, but also improve the quality of the cotton crop. Currently, Pakistani cotton is considered second grade, and if the crop quality is improved there would be greater demand at a greater price. More importantly, by improving the crop, the entire textile industry will benefit since the quality of all products will improve at source.

The 2022 anomaly

But all of this changed last year. The cotton crop that was sown in Pakistan in 2021 and was harvested in 2022 benefited from a peculiarity of international trade caused by Covid-19 that resulted in a bumper crop of cotton.

You see, cotton has been on the decline since 2008, as we have seen. As mentioned earlier in the story, between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton only declined. This led to the textile industry claiming that they would thrive on imported cotton instead of depending on local cotton. This worked out especially since the cotton Pakistan produced was second grade.

But when the pandemic hit, everything changed and the local industry found that importing cotton was no longer an option. International cotton prices (in rupee terms) during the last year have gone up by almost 30% — from PKR 12,606 on July 1, 2021, to

PKR 18,259 by mid-February this year. The ever-dwindling value of the rupee not only doubled the impact of import for Pakistani millers but also made it next to impossible to calculate the final cost of production, rendering import commercially non-feasible for the industry.

On top of this, there were shipping concerns. A report in Dawn from March 2022 chronicled how it takes more than 120 days to ship cotton to Pakistan these days, against the 30-day hiatus in pre-Covid times. These circumstances deflated the textile industry’s claim that it could thrive, even survive, on imported cotton and forced it to value local crops, thus setting the stage for the cotton revival in the country.

Since the impact of Covid was comparatively milder on Pakistan, its industry started almost eight months ahead of the rest of the world and so the entire capacity was booked within weeks. This sent the industry in a mad chase for cotton, hence improving local prices, explains Arshad.

A big part, simultaneously, was that just a year before, Pakistan had started to focus on improved cotton production methods. This is what allowed it to cover the gap for the industry when importing cotton was no longer feasible, the Dawn report adds. “In 2021, acreage fell by 17% in Punjab — from 3.8 million acres in 2020 to 3.1m last year — but production fell by only 2%.”

This means that average yield increased over time. The report quotes Dr Saghir Ahmad, director of the Central Cotton Research Institute (Multan), as saying, “the average yield jumped from 15.68 maunds in 2020 to 19.62 maunds per acre in Punjab in 2021.

In Sindh, it was even better; 30 maunds per acre, pushing the national average to 25 maunds per acre. This better production, along with a massive rise in world prices, has now set the stage for acreage expansion this year.”

Why it didn’t translate to this year

This is what it comes down to. Last year, farmers saw an opportunity where cotton demand was high and sowed more of it. As a result, outputs rose but the core problems were not addressed. Even last year, the textile industry has stayed largely unimpressed with the increase in output.

They chalked the increase up to special circumstances and still relied upon imports to run their operations. According to them, local cotton does have the potential to cover local demand but unless solid steps are taken there will be no point to it.

“This has not been a remarkable increase,” says Raza Baqir, the secretary general of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA). “There has been a marked increase in per hectare yield in some areas which is very encouraging, however, in some areas, decreasing yields have also been observed, and overall the scale has barely been budged. We still need to import nearly half of our quantity from abroad, which with rising prices is difficult. We have observed a consistent improvement since at least 2019, but overall it has to be said it was all very marginal.”

The key here is the minor improvement that has been seen over the past three years.

Before this, for nearly a decade, Pakistan’s cotton crop suffered from multiple ailments. The narrow genetic base of cotton germplasm which are prone to insect and disease, along with reliance of Pakistan on a back-crossed 17 year old biotechnology have resulted in low yield per area. Lack of quality and advanced gene technology is a serious issue that has plagued cotton productivity in Pakistan. The attack of pests such as the locust attacks in the past couple of years and other consequences of climate change have all caused issues.

In 2022, a peculiarity of the international supply chain made a case for Pakistani cottons. Just as the problems of this crop have been listed, its solutions are also readily available. Investment is required in cotton research.

More importantly, this year the price of cotton was well above the support price of PKR 5000 per bale (40KG) but the early announcement of this support price gave farmers the confidence to pursue this crop. With all of these considerations, Pakistan can once again go back to its cotton glory days, and perhaps bolster its textile industry and exports along the way.

This year has only proven the textile industry right —- that they were correct not to feel too hopeful of the brief gains made by Pakistani cotton. This year’s figures of 4.9 million bales means the textile industry will have to import around 10 million bales to satiate its annual hunger for 15 million bales. Already the textile industry has been facing issues because of severe import restrictions, with mill consumption falling to 8.8m bales, the lowest in over 20 years.

With imports in the country facing the chopping block because of the ongoing economic crisis, 2022 was an ideal time to encourage farmers to continue to grow cotton and encourage the textile industry to invest in local cotton. However, this year’s output indicates that the stocks of the cotton crop are likely to fall further. Only time will tell how low they will go. n

The Lahore Railway Station is a majestic and awe-inspiring structure, one that exudes an air of grandeur and history. It is a living, breathing entity that holds within it the secrets and memories of Lahore’s past. The station’s magnificent Mughal and Gothic Revival architectural styles serve as a reminder of its soul, a nod to its colonial history and the era of the British Raj. As you step inside, you are transported back in time, as if the station itself is a portal to the past. The echoes of footsteps from those who have come before you reverberate through the halls, and the air is thick with the fragrance of bygone eras.

By Daniyal Ahmad

Gandhi and his band of activists once marched through its halls, their calls for freedom ringing out loud and clear against the oppressive 1919 Rowlatt Act. The station played a pivotal role in the violent birth of our nation, serving as a gateway for millions of refugees fleeing the trauma of partition; it witnessed both the joys and sorrows of a people fighting for independence with a front-row seat to the separation of India and Pakistan in 1947.

The signs of neglect and decay however, have become increasingly pronounced. The once-grand walls, with their ornate carvings and intricate stonework, now bear the scars of time and the indifference of those in charge. Cracks and missing tiles pockmark their surfaces, while layers of grime, peeling paint, and water stains cover every inch. The columns and archways, which were once adorned with the finest details, are now a shadow of their former selves, barely visible under layers of dirt and neglect. The station seems to have been left to fend for itself against the ravages of time and the chaotic streets outside.

A lack of investment, alleged corruption, and general mismanagement have led to a decline in services and passenger numbers.

However, this might be about to change as Pakistan Railways looks to entice advertisers with their wares. The aim is to monetise existing assets in order to resurrect the national railway service. The question is, what’s the courtship that Pakistan Railways has planned and will advertisers play ball? Profit looks to explore exactly that.

What’s on offer?

“Advertisers will have access to the physical premise of the Lahore Railway Station. They will have access to the parking area, platforms, staircases, bridges, and other infrastructure at the Lahore Railway Station,” says Najam Saeed, Chief Executive Officer of Railway Constructions Pakistan Limited (RAILCOP). “Furthermore, two trains will also be available for advertisers to use. They will be allowed to utilise the space available inside the trains, and also wrap the exterior of the train too. Finally, we will also float various railway crossings/phataks alongside some other properties owned by the Pakistan Railways across Lahore,” Saeed continues.

“It’s a new medium of advertising altogether,” muses Saeed. “While television channels are limited to selling minutes, we have more to offer. We can sell minutes on our in-train infotainment systems, but we can also offer advertisers feet and inches. Advertisers can showcase their products and services in a variety of creative ways, using the space we have available to sell to advertisers,” Saeed adds.

For anyone wondering as to why Profit did not reach out to Pakistan Railways itself. Well, we did. Profit spoke to Naeem Sadiq Sheikh, Chief Executive Officer of the Pakistan Railways, who redirected us to RAILCOP. RAILCOP is a subsidiary of Pakistan Railways spearheading the endeavour. Back to the fun now, why is Pakistan Railways doing this?

Why is Pakistan Railways doing this?

The answer to this is very simple; Pakistan Railways does not have a lot of money, but it does have a lot of land.

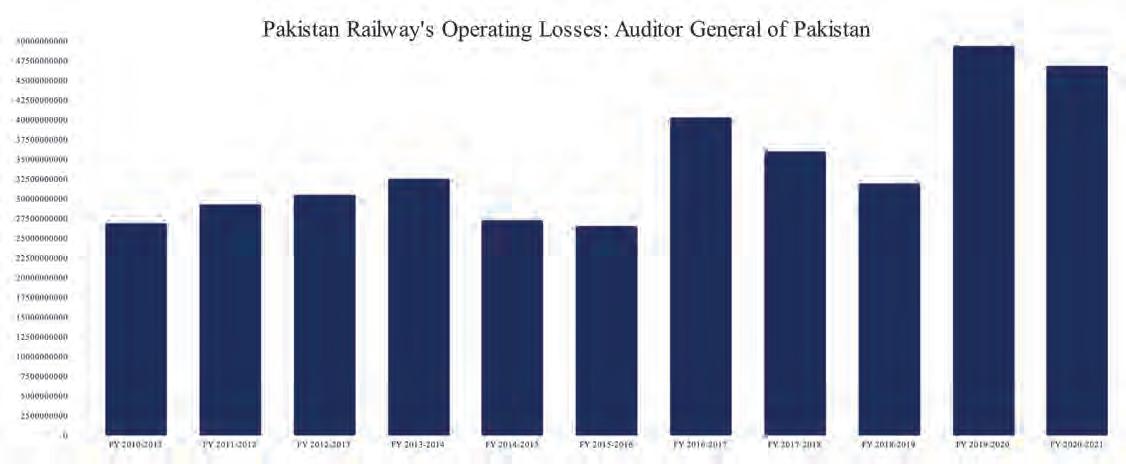

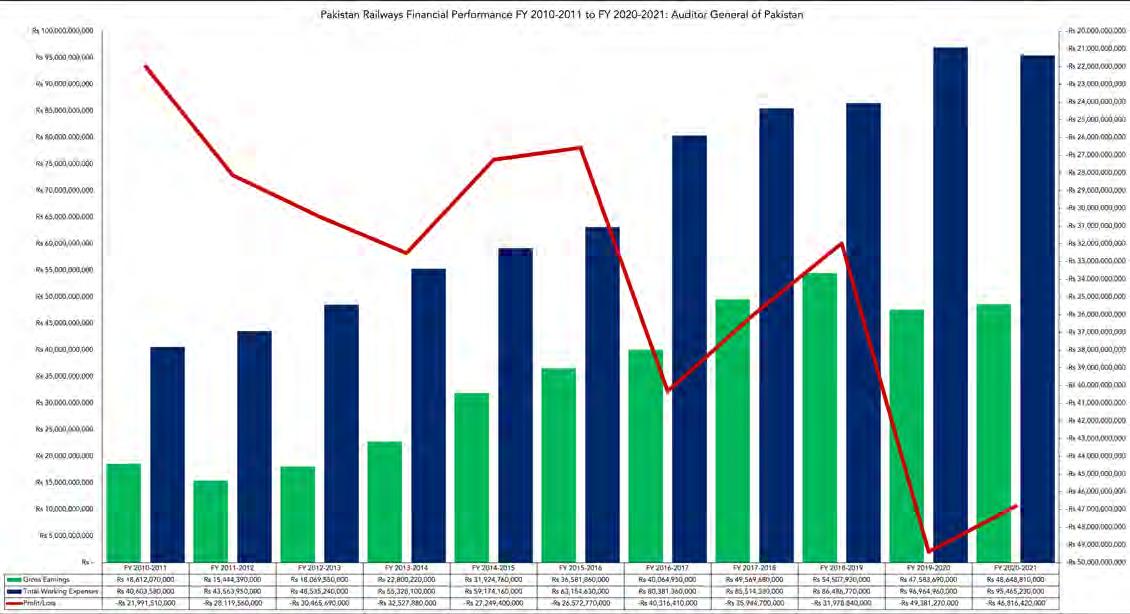

According to audits conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Pakistan, Pakistan Railways has experienced financial losses every year from FY 2010-2011 to FY 2020-21. Its revenue has consistently been able to cover only half of its expenditure bill, with the amount rising from 46% of expenses in FY 2010-2011 to just 51% in FY 2020-2021. The average annual loss during this period was Rs 34 billion.

Pakistan Railways is, evidently, broke. Its CEO believes advertising is a possible much-needed fresh revenue stream. Pakistan Railways has 168,500 acres of land across Pakistan to be precise, according to the aforementioned latest audit report. If this pilot project of theirs works out, then they could potentially generate a lot of revenue.

There’s also another monetary aspect to this that the Railways is looking at, and that is possibly outsourcing part of, if not the entire, cost of maintaining their existing infrastructure. The thinking behind this is that brands buying the variety of spaces on offer for advertising will have an incentive to keep them well-maintained to get the most out of them.

“Effective branding can enhance the aesthetic appeal of infrastructure if implemented wisely. Additionally, the areas that display advertising are more likely to be well-maintained, as companies avoid advertising in unappealing locations,” explains Saeed in an interview with Profit. “There are numerous damaged railway crossings throughout Lahore without any service guards present. Similarly, many high-traffic areas across Pakistan have similar crossings that could provide valuable brand visibility. By utilising these crossings for advertising, revenue will be generated to maintain and hire staff for these locations - either by the Railways or even the brand themselves,” adds Saeed.

“Advertising always benefits infrastructure. The sponsors of the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB), and the Pakistan Super League (PSL) pay for the super league to happen. Right?,” explains Atiya Zaidi, Managing Director & Executive Creative Director at BBDO. However, as Zaidi points out, these are clearly delineated as part of the contract. Whether the Railways can force through agreements such as these is debatable.

“Advertising enables entities to do the things they want to do. In the long-run, the advertising earnings can be used to improve the Railways’ infrastructure and maybe benefit Pakistan as a whole,” Zaidi adds.

But can the Railways actually sway the agencies that place the ads?

What do advertisers make of this?

reative design in mass transport or mass transit vehicles such as buses and subways has always existed. No matter how digital we become, subways and trains limit phone connectivity. While the world is moving towards digital, out-of-home advertising at train, railway, tube, and bus stations, as well as inside buses, will always remain effective because it targets a captive audience,” Zaidi explains.

“It’s like advertising on a plane. Passengers can’t exit the vehicle, and their phones don’t work, so they’re more likely to pay attention to the advertisements. In terms of getting eyeballs, it is always a good investment,” Zaidi adds.“It’s a very good opportunity because there are millions (28.24 million in FY 2020-21, to be exact) of commuters that use Pakistan Railways,” Agha Zohaib, Managing Director at Mindshare, tells Profit.

“It’s a great thing on paper. They should have done this a long time ago, but this is not where the buck stops. They have to take measures to make sure that they can sustain it,” says Saad Khalique, Director of Operations at Orient McCann. “If they simply collect the mobile numbers and/or email addresses of their passengers, or implement a radio frequency identification (RFID) system in the ticketing that links to the customers’ phones, it would open up new avenues for agencies. They could engage in remarketing campaigns and better connect with passengers as potential customers,” Khalique suggests.

According to Zohaib, there are many benefits to using railway platforms for advertising beyond branding. “It’s a good opportunity, not just from a branding perspective, but also for brands that want to engage with customers one-on-one. There’s the potential to move beyond static billboards and incorporate video or audio elements, or even conduct activation activities,” he explains.

“In addition, the closed environment of the train bogey presents unique opportunities for conducting research and gathering feedback. Brands could more easily entice people to give feedback in this setting, and companies like telecommunication providers could potentially offer WiFi on the bogeys to conduct speed tests for their devices,” Zohaib suggests.

“It opens up new opportunities for creativity as well. There are a lot of companies that operate across the country, and you’re on that journey as a potential customer right?,” says Zaidi. “It is an exciting medium for sure. However, the key question will be what the return on investment (ROI) will be for the brands that do decide to invest. Another question that the Railway will have to answer is as to who will undertake the cost of setting up the requisite advertising infrastructure,” adds Zaidi.

This is where our positives end. Let’s start with the latter of the two concerns first.

The devil is in the contractual details

“Alot of the time brands get slack for their out-of-home advertising such as billboards collapsing,” muses Zaidi. “That’s not the brand’s fault, but rather the fault of the company that instals the structure sporting the advert,” she adds.

“Advertising in this manner has never been attempted before, correct? Therefore, it will be necessary to install the necessary infrastructure not only at the stations but also inside the trains and anywhere else the Railway wishes to promote brands. As these are outdoor trains, it’s not possible to simply paste advertisements on the tunnel walls like in indoor tube stations. Instead, we’ll require outdoor billboards. This infrastructure incurs a cost, and safety is a significant responsibility that must be addressed. These are questions that will need to be worked out between the brands and the Railways,” Zaidi continues.

Depending on the agreement that the Railways sign with their advertisers, they may end up incurring additional expenses to get their advertising initiative rolling. This detail is crucial as it will determine whether the Railways will have to bear the cost of maintaining aesthetically pleasing areas where branding will be displayed. Saeed’s assessment that advertisers prefer attractive areas is accurate, but it’s important to note that the upkeep of such areas comes at a cost. The responsibility of bearing this cost will be outlined in the fine print of the agreement.

“Consider the People’s Bus Service in Karachi. Brands wrap their advertisements around these buses because they are aesthetically pleasing, air-conditioned, and well-maintained. As long as the buses remain in good condition, the brands will continue to use them as a platform. However, if the quality of the buses declines, brands will withdraw their advertisements from them,” Khalique explains. “It’s the same for the Railways. As long as they provide quality infrastructure, brands will continue to allocate their advertising expenditure and vice versa,” he adds.

Now let’s address the other issue that Zaidi raises - the elephant in the room: are the brands that media agencies represent interest-

ed in participating in this Railway initiative?”

Convincing the actual brands to place their advertisements

“We’re always looking for mass media options. The Railways hasn’t been explored in the past so we will have to test its effectiveness, but I believe there’s appetite for this amongst brands,” says Zohaib. Zohaib’s hesitance is natural given an initiative as nascent as this.

Meanwhile, Khalique acknowledges that the initiative seems promising on paper and says, “The assumption is that it works in other parts of the world so it will work for us too. The world is making money through this, so should we,”. Zaidi, however, puts the dilemma aptly. The primary question pertains to who the companies deal with from Pakistan Railways; their competence and authenticity will determine the confidence brands have in this initiative. The Railways will need to deliver the return on investment (ROI) they promise companies who partake in this,”.

Saeed opines on the matter by telling Profit that, “Advertising initiatives have never been undertaken in a scientific method by the Railways before,”. He promises that there is a method to the madness. What do we mean?

Shooting darts in the dark?

Saeed used the word scientific. It’s not a slip of tongue, its use is deliberate. That is because the ROI can be calculated in-advance.

“Companies will always conduct a certain ROI assessment in terms of eyeballs. For out-of-home advertisements, it’s usually the number of people that see the advertisement, the traffic where the advertisement has been placed, etc. This will always be the question that brands will ask especially for mediums

“Since these carriages are unlikely to be seen by customers of corporations whose ads we’ll be placing, it is crucial that our data set is solid. Our measurements must be transparent and intensive,” Khalique adds.

Saeed acknowledges that the Railways does not have immediate data on hand to present, “Customer behaviour is an entire world on its own. The need of the hour for us is to see how many passengers we have, and subsequently how many eyeballs we can attract,” he says. “This is a pilot project. We can collect and analyse more data as required, going forward. There will be innovations based on the learnings that we obtain once it gets rolling. The important thing is to get it off the ground for now,” Saeed adds.

Whether the Railways’ learnings will translate into tangible improvements within a year is debatable. “In my opinion, governmental organisations are generally bureaucratic and slow. If the Railways’ plans are as ambitious as they claim, they should have the means to implement them,” Zohaib opines. “Governmental organisations have a top-down approach. If the person at the top wants it done, everything noted that the current Federal Minister of Railways, Khwaja Saad Rafique, in his address, acknowledged that the previous initiative failed due to a lack of professional expertise in branding. He added that the Minister is now confident that the necessary expertise is available to make the current project a success.

Yet, there remains a concern about the timing of the project. Saad Rafique, was also in charge of the previous initiative. With the political turmoil that has plagued Pakistan, there is uncertainty about what would happen to the project if he were to lose his position.

“Advertising for any government in Pakistan carries a lot of political innuendos, which brands generally prefer to avoid. No brand wants to be involved in a political conflict. They don’t want to take sides, especially in Pakistan. While brands may do so internationally, that is not the case for brands in Pakistan,” Zaidi opines on the matter. Zohaib, and Khalique share the same reservations on the matter.

such as transit,” says Zaidi

According to Saeed through the Lahore Railway Station, Pakistan Railways aims to cater to an “accumulated 150,000 personnel per day consisting of passengers departing, arriving, and railway station visitors,”.

“The biggest challenge however will be collecting data on the rail carriages. While data for other infrastructure provided by the railways can be corroborated with third parties, this cannot. Pakistan Railways operates primarily intra-city, meaning that the rail carriages will pass through low-population-density areas in the suburbs. Consequently, very few people will see the ads we place, and even those who do may not have the purchasing power to act on the advertisement,” explains Khalique.

will be done,” remarks Khalique. However, the opposite is also true.

Navigating the current political rigmarole

Pakistan Railways has attempted to monetize its assets through advertising in the past. However, a 2014 pilot project that offered branding opportunities to companies on the Tezgam, Khyber Mail, and Awaam Express trains, such as on seat covers, internal walls, and toilets, failed to take off, and all plans for a revival had remained dormant.

Saeed, in a conversation with Profit,

Although Saeed is optimistic that the railway’s gains from the advertising initiative will garner bipartisan support, advertisers are understandably cautious about accepting such claims at face value. “While Pakistan’s bureaucracy is well-equipped to ensure the project’s long-term viability and make necessary improvements over time, we cannot ignore the political pressures that come with their roles,” Khalique adds.

Additionally, the red tape and general inefficiency that plagues public sector enterprises makes for a difficult and time consuming execution.

The Railways’ upcoming pilot program is a gamble, and it’s anyone’s guess whether they’ll learn from it and introduce the incremental improvements needed. While brands may be tempted to support this initiative out of a sense of national pride, financial viability is the key to its long-term success. At the end of the day, ROI - not patriotism - determines the flow of capital. Without a solid commercial foundation, this passion project could be nothing more than a momentary burst of excitement, fizzling out into obscurity. n