10 minute read

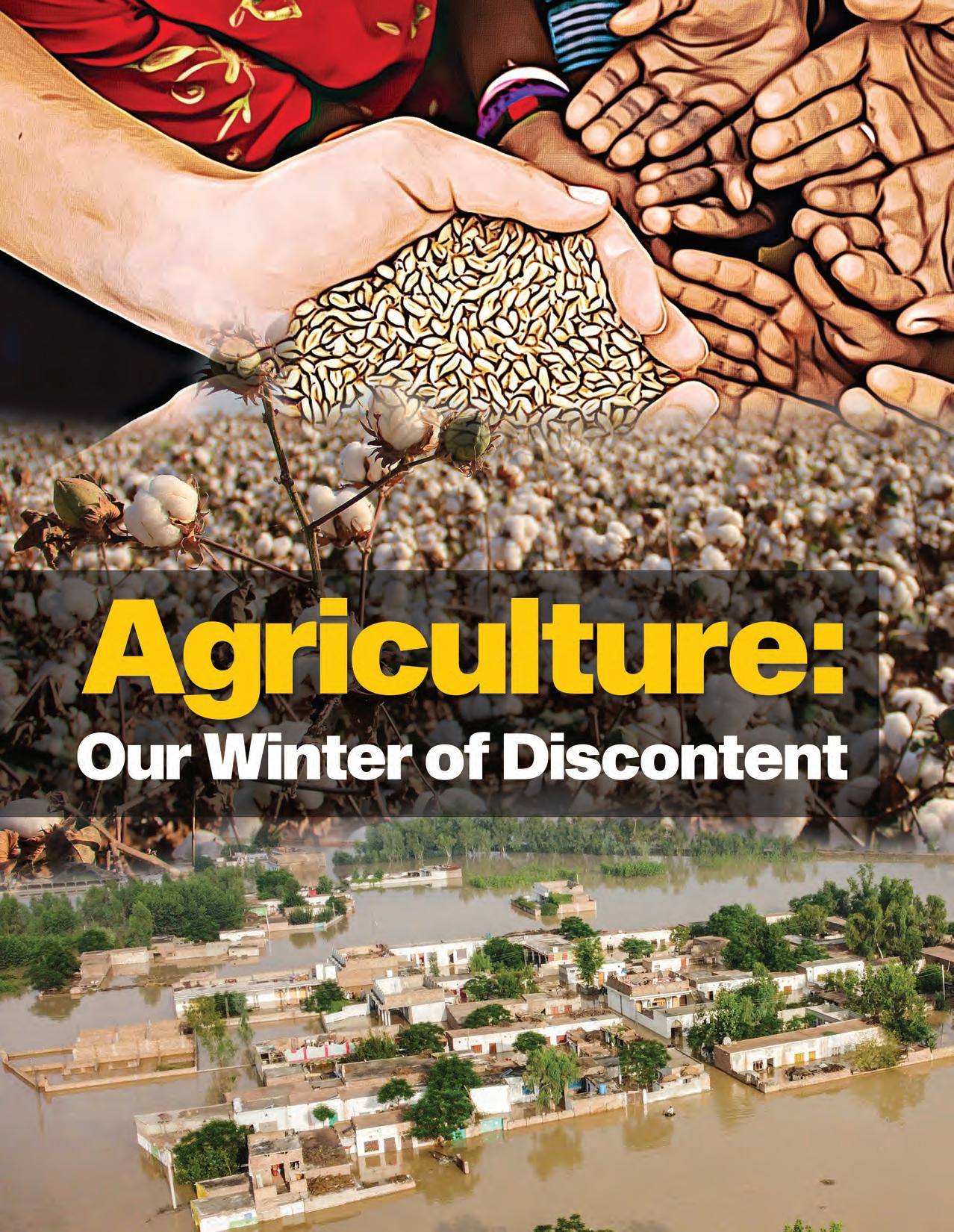

Agriculture: Our Winter of Discontent

This is the story of two different days at the same place in the same year. In May 2022, reports began to emerge that the cotton crop in Sindh was wilting. In Sanghar, one of the largest cotton producing districts in Sindh with cotton grown on 300,000 acres of agricultural land, less than 200,000 acres were being used to cultivate cotton. And on the 200,000 acres that were being used to grow cotton, crop performance was abysmal.

While the cotton crop in Sanghar suffered, other agricultural areas dependent on the down-river water from the Indus were affected as well. In Thatha, fishing villages were left without any source of livelihood as the nearly three kilometre stretch of river that crossed the region dried up completely and was replaced by huge deposits of sand. At the Kotri Barrage of the Indus in Sindh, water levels had fallen from 15,000 cusecs of water to barely over 2000 cusecs.

Advertisement

Figures from May this year showed that a major dip in the Indus of 10,000 cusecs (an outflow of 105,000 cusecs on May 19 and 95,000 on May 20) occurred at Tarbela dam, raising fears that the dam may have hit dead levels. Its inflows plunged to 77,900 cusecs on Friday from 98,000 cusecs on May 14. These flows are to be used Taunsa upstream in Punjab and in Sindh. The dam’s level stood at 1,406 feet on May 20 against 1,414 feet on May 16.

All of these are signs of the times. And while they are warning signs, they are not indicators that can help us predict the future.

A few months later in August, the entire district of Sanghar had been submerged in water nearly five feet deep in areas. The entire village of Chak 7 has been displaced and wiped out. More than 100 kilometres away in Sukkar, a similar story of devastation reigns. These are just a few pictures of the misery that the still raging floods in the country have caused.

Within the course of a few months this small village in Sindh had gone from being shrivelled to entirely waterlogged. This is the threat that has faced our agriculture for a long time, and has made itself very obviously known in this past year. In what has possibly been a historic year for Pakistan’s agriculture, and not in a positive way.

The Indus is dying

For decades, the Indus River has been suffering. Since the middle of the 19th century, it has undergone severe changes due to the development of the Indus Irrigation System, the building of dams and barrages. Since the 1947 partition, the Indus River Treaty of 1961 has also contributed to the unnatural ebbs and flows of the river. All of these have had adverse effects on the water levels of the river and its different tributaries, and in turn has had an effect on the country’s agriculture. Now, however, we are beginning to see the emerging effects of climate change as well.

While it has faced both natural and human changes, the Indus has thrived off the basis of glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau. With climate change knocking on the door, that too might be a thing of the past. It is an issue facing many of the rivers that are fed from the Tibetan plateau. Mountains are the water towers of the world, especially in the case of Asia, whose rivers are all fed from the Tibetan plateau and adjacent mountain ranges. More than 1.4 billion people depend on water from the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, and Yellow rivers which are fed by these water towers. Upstream snow and ice reserves of these basins, important in sustaining seasonal water availability, are likely to be affected substantially by climate change, but to what extent is yet unclear.

What is clear is that the early effects are already visible. In an article published in the journal for Global and Planetary Change, a report on the state of the Tibetan Plateau published a few years ago reads that the region has faced “evident climate changes, which have changed atmospheric and hydrological cycles and thus reshaped the local environment.” The report claims that “the Tibetan Plateau (TP) exerts strong thermal forcing on the atmosphere over Asian monsoon region and supplies water resources to adjacent river basins, and the effect of climate change on this region will have an impact on the Plateau energy and water cycle.”

The effects in Pakistan are clear. Erratic water levels, flash floods, and droughts all indicate that the river is in trouble. Meanwhile, priorities remain things like the Ravi Urban Development Project which has been earmarked as a future environmental catastrophe.

The floods

The biggest news this year not just in agriculture but in the entire country and possibly the world this year were the floods in Pakistan. In short, climate change has resulted in a gargantuan increase in the amount of monsoon rainfall that Sindh and Balochistan have seen this year. The two provinces saw the highest amount of water fall from the skies in living memory, recording 522 and 469 per cent

more than the normal downpour this year according to the met department. “Sindh has received 680.5mm of rain since July when the monsoon season actually began,” said a Met official.

“As per calculated and defined standards, Sindh normally gets 109.5mm of rain in the monsoon season. So it’s 522% higher than normal. Similarly, Balochistan receives 50mm rain on an average every monsoon, but it has so far recorded 284mm — 469% higher. The country has overall witnessed 207 times higher rainfall so far this monsoon and the season is going to last till September-end.”

The main reason behind the flooding has been this abnormally high rainfall causing hill torrents — which are a distinct type of waterway in which water drains from the mountains and hits localities and infrastructure in its path at an enormous speed. More than 200 hill torrents originate from the west of Suleiman Range and hit Taunsa, Dera Ghazi (D.G.) Khan and Rajanpur Districts of Punjab in Pakistan. Among these, 13 hill torrents have large catchment areas and flood potential. All of these have realised this potential this monsoon season at the same time. The discharge at Taunsa, Guddu & Sukkur barrages is more than Twice that of Kalabagh and Tarbela, showing that the additional water is coming from Koh-i-Suleman hills and torrential rains. Dams would not have stopped this overflow, particularly since the Indus is not overflowing, it actually has levels of water.

This has caused destruction in Balochistan and South Punjab, with the rains and a swollen Indus river delta wreaking havoc in Sindh. In KP, meanwhile, flash floods coming from fast melting glaciers have overrun shoddily and dangerously built constructions on the banks of rivers. The main cause behind the flash floods has been the inflow of heavy rains and a massive river current from the Kabul river that has overrun the province. In KP, in fact, while the Kabul river swelled because of excessive monsoon rains, with KP recording a 50% increase in the level of rain, one of the major reasons for the flash floods were cloud bursts in the Swat and Mingora regions that overran the Swat river and swept away hotels and buildings on the embankments. The met department, according to an anonymous source, did not pick up on the cloud burst and issued no advisory for it.

The economic impact alone has been devastating. All in all, according to the latest report of the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), Pakistan needs at least $16.3 billion for post-flood rehabilitation and reconstruction. The PDNA report, released by the representatives of the government and the international development institutions, calculated the cost of floods at $30.1 billion – $14.9 billion in damages and $15.2 billion in losses. “Our priority is an adaptation for long-term measures to ward off climate change impacts. Pakistan is in the front line for advocacy and played a proactive role for highlighting climate finance. Our efforts will be focused on seeking $100 bln per year as promised in 2009 for climate finance and do the advocacy to increase the pledge three times,” adds Rehman.

Yet beyond this immediate need for reparations, Pakistan also needs a clear agenda on what it wants to do on the climate front. There is the immediate concern of rising temperatures, for example. According to Ali Sheikh, an expert on climate change and development, it is in the fundamental national security interest of Pakistan that global average temperatures stabilise at 1.5 degrees Celsius, since a change of 1°C has already caused serious disruptions and brought the economy to its knees. If no action is taken, Pakistan, like many other developing countries, will simply not have the residual resilience to cope with recurring climate disasters.

COP27

This has been our one gloomy grey-lining. For once, Pakistan was a major centre of attention at this global conference. The reason behind being in the spotlight was the impact of this year’s devastating floods that ravaged millions, destroyed crops, levelled entire villages, displaced 33 million people, and caused an estimated $40 billion in damages all over the country.

According to the Center for Global Development, developed countries are responsible for 79% of historical carbon emissions. Yet studies have shown that residents in least developed countries have 10 times more chances of being affected by these climate disasters than those in wealthy countries. Further, critical views have it that it would take over a 100 years for lower income countries to attain the resiliency of developed countries. Unfortunately, the Global South is surrounded by a myriad of socio-economic and environmental factors limiting their fight against the climate crisis.

The hotly contested issue of climate reparations, in particular the establishment of a financial mechanism for addressing the irreparable losses and damage caused by climate-induced extreme events in least developed countries, was always going to stir controversy. This was encapsulated best, perhaps, by the response of the United Kingdom. Recently elected Prime Minister Rishi Sunak briefly attended the conference and reaffirmed Britain’s commitment but remained quiet on the issue of reparations, “despite British negotiators backing a last-minute agreement to address reparations to countries suffering the worst impacts of climate change, with Pakistan leading the push for such a commitment,” according to a recent article in The Guardian.

The immediate worry is whether or not we will be able to spend the money right. Climate change has two key impacts. The first is to increase heat and carbon in the air. The other precipitation variability — which means changes in the trend of rainfall. In the short term, some of these conditions might even result in better yields for some of our crops but at the end of the day it will be fatal for our agriculture. We will start seeing deficiencies in micronutrients in different crops which could result in nutritional deficiencies in the population. The private sector is already adding these nutrients to products such as rice artificially but this will only further increase the economic disparity that exists in our country.

Food security

Pakistan has a problem. In an international ranking of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) this year, the country ranked 92 out of 116 nations, with its hunger categorised as ‘serious.’ Pakistan currently faces a scenario in which it is largely food sufficient but not food secure. Despite Pakistan being ranked at 8th in producing wheat, 10th in rice, 5th in sugarcane, and 4th in milk production, a 2019 report of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) showed that nearly 37% of households in Pakistan are food insecure. At the end of the day, this is what it essentially boils down to. In a country like Pakistan, food sufficiency is the most important thing there is and at its core is the agriculture issue. In the three years since the SBP’s report, matters have only worsened. Food price inflation in Pakistan has been in double digits since August 2019. The cost of food has been 10.4-19.5% higher than the previous year in urban areas and 12.6-23.8% in rural areas, according to figures published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. So how does a country with one of the largest agrarian economies in the world find itself unable to sufficiently provide food for nearly 40% of its population? For decades, agriculture has been neglected and people’s earnings have been hit by one economic crisis after another. On top of this, particularly in the past decade or so, climate change related disasters and changes in the environment have resulted in our already neglected agriculture becoming less competitive.n