10 minute read

Crop Talk: From no potatoes to too many

From no potatoes to too many

One of Pakistan’s mightiest crops, the potato has suffered from overproduction and lack of government attention

Advertisement

By Abdullah Niazi

At the British library in London, tucked away in their vast collection is the Nimatnama — The Book of Delights. This incredible manuscript holds within it a wealth of recipes from the court of Sultan Ghiyas al-Din Khilji, the 15th century ruler of the Malwa empire which had seceded from the Delhi Sultanate.

By all accounts, the book is a fascinating exploration of the cuisine of its time, detailing in meticulously written Naskh script the recipes and cooking techniques that went behind some of the Sultan’s favourite dishes. It is a thoroughly gluttonous book. It provides very specific instructions to prepare mouth-watering dishes featuring quail, partridge, mutton, all cooked in generous amounts of ghee and flavoured to the teeth with cardamoms, cloves, coriander, fennel, cinnamon, cassia, cumin and fenugreek. Yet, perhaps one of the most fascinating parts of the entire book are the eight different recipes it provides for samosa — none of which feature potatoes in any way, shape, or form.

The case of the missing aloos in the Nimatnama has been documented, discussed, and dissected before this. Today, the first thing you think of when a samosa is mentioned are potatoes. Yet this lumpy, brown, root that is an incredibly common part of pantries all over the subcontinent is neither native to this land nor has it been around for too long. The first potatoes were brought to India from Peru by Dutch settlers in the late 17th century and planted along the Malabar coast. However, it would not be until the late 18th century, when the British would promote the growth of potatoes all over the subcontinent, that they would quickly assimilate into Indian cuisine and become a vital if oft-ignored hero of many dishes.

So think, for a moment, about this humble vegetable. Once the sole property of native Peruvians, its journey across the New World to Europe and then Asia beyond it has in only a couple of centuries turned it into the fifth most important crop in the world after wheat, corn, rice, and sugarcane. Easily grown, versatile, and, most importantly, delicious, good potato crops have

managed to feed entire nations, while bad harvests have led to famine, starvation, and death. So what is the state of potatoes in Pakistan?

Largely, they have thrived. Potatoes are not only a major caloric input in our national diet, but a major component of the snacks industry. Yet, while the crop itself has thrived, governments have often been left unprepared and red-faced, not being able to deal with overproduction and unhappy farmers. But what more can be done, and exactly how vital is the potato crop for Pakistan?

Humble origins Nothing to do with potatoes, but a recipe from the Nimatnama

Another recipe for the method of saffron meat: wash the meat well and, having put sweet-smelling ghee into a cooking pot, put the meat into it. When the ghee is hot, flavour it with saffron, rosewater and camphor. Mix the meat with the saffron to flavour it and when it has become well-marinated, add a quantity of water. Chop cardamoms, cloves, coriander, fennel, cinnamon, cassia, cumin and fenugreek, tie them up in muslin and put them with the meat. Cook almonds, pine kernels, pistachios, and raisins in tamarind syrup and add them to the meat. Put in rosewater, camphor, musk and ambergris and serve it. By the same method, cook partridge, quail, chicken and pigeon.

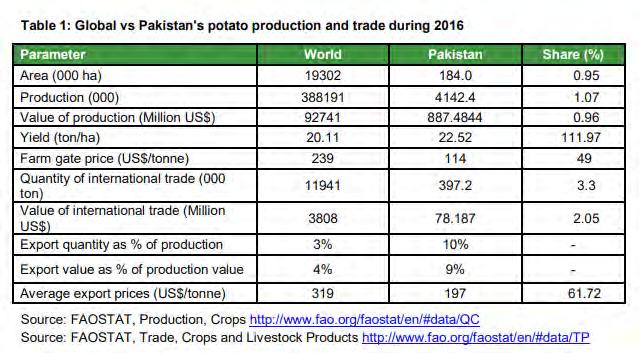

In 1947, potato cultivation in Pakistan was restricted to a few thousand hectares and total annual output was less than 30,000 tonnes. Most of the potato plantations that the British set-up during their time ruling the subcontinent were outside of the lands that became Pakistan. Yet by the time of partition, potatoes had become a common enough crop that their cultivation immediately saw an uptake given the demand. According to a 2020 report of the planning commission, in the decades since independence, the potato has become the country's fastest growing staple food crop as strong gains in cultivated area and average yields have been achieved. There is no real secret to this success. Potatoes are an incredible vegetable that grow in a vast variety of conditions and soils, and are more than receptive to Pakistani conditions. In fact, in Pakistan the average yield per hectare is 12 times the world average. The agricultural statistics of 2017 show that potatoes are grown on 177.8 thousand hectares producing a total of roughly 3.8 million tonnes with an average per hectare yield of 22.5 tonnes, which is about 12 times higher than the world average. The value of the production is worth $483 million.

The star of the show has long been Punjab, which produces 93.6%, followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (5.17%), Balochistan (1%) and Sindh (0.33%). Potato consumption in Pakistan is showing an upward trend, now annual per capita intake is over 15 kg, up from around 10 kg a decade earlier. Over the years, despite not being historically rooted in the region, potatoes have become one of the principal cash crops of Pakistani farmers and the primary exportable horticulture commodities from the country. It is the fourth most significant crop in terms of bulk production, and one of the very rare cases in which Pakistan is not just self-sufficient for domestic use and seed development, but also an exporter.

Exports and local use

Perhaps one of the biggest reasons behind this is that the snacks market in Pakistan relies heavily on local potatoes to make their products cheap and accessible. The processed potato market of the country mainly consists of four major products: Potato chips, french fries, potato flakes/powder and other processed products such as dehydrated chips, starch and flour.

The biggest player out of these is the potato chip industry by a landslide. Potato chips currently constitute 85% of the snacks business. The impact can be measured from the fact that the utilisation of raw materials by the potato processing industry in 2014 was about 40,000 tonnes, which is hardly 1% of the overall total production. During 2017, about 214,000 tonnes of potatoes were processed by processing industries which is about 6.3% of total produce and out of which a major share of more than 70% was because of Pepsico, which produces products such as Lays potato chips.

Meanwhile, surplus potatoes are exported to the UAE, Malaysia, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. In 2017-18, 570,000 tonnes of potato was exported to these countries, which earned about Rs11.8 billion in revenues. Pakistan’s export of potato increased from 272,800 tonnes in 2011-12 showing an average growth rate of about 11%. However, this surplus has often been a problem for farmers. The cost of growing potatoes is quite high, and, when there is overproduction, the price of potatoes falls on the market and farmers go into loss.

The overproduction issue

In 2019, Kasur was up in flames as farmers from all over the district burned the potatoes they had grown that year and marched demanding the government set a support price mechanism for their produce as a protection against negative market forces. They later staged a sit-in outside the Punjab assembly. Punjab, particularly the 12-district belt that runs from Kasur to Khanewal district in the south, is the hub of potato production in the country. Potato acreage has been increas-

ing on a year on year basis. That is because the crop is always in demand, and resilient in the face of weather and calamities. However, the increased acreage and yield has resulted in a situation where potato farmers regularly face the brunt of potato prices being very low on the market. As a result, sometimes they are not able to break even.

Potato Growers Society Vice President Chaudhry Maqsood Ahmad Jatt claims that the total cost of a bag of potatoes, from sowing up till its transportation to the market, stands at over Rs2,000. Yet when the crop yields more potatoes than expected in any given year, there is the sudden problem that prices are well below this.

Despite the protestors being sent home packing with promises, very little was done to announce a support price. The problem once again reared its ugly head earlier this year. In February, then finance minister Shaukat Tarin directed the Ministry of National Food Security and Research to come up with a strategy to export the surplus potatoes that would be grown that year. The country was expecting a record harvest due to increasing acreage and better-than-usual weather conditions.

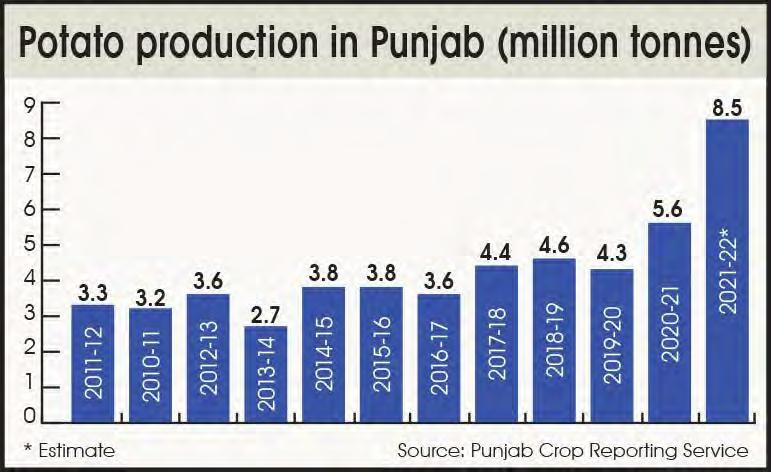

The only problem was that we didn’t know what to do with all of these potatoes. The Federal Committee on Agriculture had fixed a target of 5.96 million tonnes of the crop for Punjab on 546,000 acres – an average of 273 maunds per acre. However, according to the Punjab Crop Reporting Service, the acreage has grown up to 740,000 acres — an increase of around 35.90% — this year.

By May, things were in motion. A record crop had been harvested — more than twice the size of the harvest in previous years with 8.5 million tonnes of potatoes produced in 2021-22 in Punjab alone. As a result, the export of potatoes rose by 10% from Pakistan according to data from the commerce ministry. export value rose 9.8% to $87.39 million in 2020–21, up from $79.59 million the previous year.

However, farmers were once again facing the brunt of the problem. They had far too many potatoes and, as a result, the prices in the market were low. There can only be so much demand, and even the 10% increase in exports was not enough to cover the overall increase in the potato crop which had risen by nearly 40%.

So what’s the issue?

Normally, when discussing any crop in Pakistan, the issues are all quite similar. They need more attention, more research, more resources, and better farming techniques to increase the per hectare area yield. With potatoes, the problem is the opposite. Too many people are growing them and the yield is incredibly high, which means it ends up being bad for business.

The answer, however, is not to curtail how much we are growing, but to capitalise on it. The problem is that Pakistan has never exported more than 550,000 tonnes, which was during 2018-19. In the next two years, they fell to 339,000 tonnes and 314,000 tonnes, respectively. Even with the increase of 10% in exports in 2022, that still leaves a lot of potatoes that are going to waste and for which farmers are bleeding money.

The potato value chain only has a better rate of return for various actors when market prices are good, according to the planning commission report. “The real fears of farmers, however, do not come from market factors but from the government’s potato policy, which farmers say works against the potato sector. For example, whenever prices start going up, the government either bans exports or allows duty-free imports from the neighbouring country India or unleashes the district administration at the retail sector to keep rates down. Farmers say they can deal with market realities, but the government should reconsider its policy for potato crop on a reality basis,” reads the report.

High seasonal and year-to-year price movements seriously affect small growers who lack the financial resources and resilience to cope with such fluctuation. There is no proper mechanism to deal with instability in the potato market, and no such solution will be found until a well-thought-out potato policy is announced. On top of this, local markets are deeply inefficient. Small-scale potato growers need access to profitable emerging domestic markets – such as the rapidly growing processing segment – as well as to potato export to high-end markets. With Pakistan’s capacity for potato management very low compared to its production, we are stuck in a world where there are more potatoes than we can handle.

So when life gives you potatoes, you increase capacity and export them. n