28 minute read

In its ambition to buy a bank, is Pakistan’s fintech poster-child about to shut down?

On the 1st of March this year, Talal Ahmad Gondal resigned as the CEO of Pakistani fintech startup TAG. The resignation was not a peaceful one. Behind it was a dicey series of events that began with TAG trying to buy a bank, and ended with an explosion of a tampered document, childhood friendships gone wrong, a cloak-and-dagger environment within the startup’s upper management, and the SBP suspending expansion in TAG’s pilot operations. How did Talal Ahmad Gondal, whose initials gave the company the name ‘TAG,’ find himself in this situation? Ask him and he will tell you that his co-founder used a serious oversight on his part to orchestrate a coup against him. Ask Ahsan Khan, Talal’s former childhood friend and the co-founder of TAG who is now up in arms against him, and he will tell you that Talal was directly involved in forging official documents that were then sent to the SBP, and that his actions were singlehandedly running the entire company to the ground. The truth is somewhere in between. Yes, there was a doctored document. It was a letter that said TAG had entered into a partnership with a Hong Kong based investment firm which had promised $45 million to help TAG buy Samba Bank. It has now been discovered that the Hong Kong firm only expressed interest in joining TAG in buying Samba and never mentioned the $45 million, which is where the tampering is supposed to have happened. Talal has admitted that the document was sent by TAG and that it was his oversight since he was the CEO, but maintains that he did not send it. He claims the letter was then used in a conspiracy to try and oust him from his position. Right now, Talal does not have an official title at the company but is practically still running the show as a 55% majority shareholder — who is at the same time under investigation. Well placed sources have said that TAG might get away with the entire fiasco with a slap on the wrist, but at the same time if the SBP decides to take serious action against Talal and TAG, it might prove to be a death knell for the startup. But why on earth was a fintech startup like TAG trying to buy a commercial bank, and why were they desperate enough to try and tamper with a document being sent to the central bank? At the centre of it is how the business of financial technology works, and why every fintech with enough money would be ready to give an arm and a leg to get a banking licence. The entire story has a messy trajectory and a colourful cast of characters. Involved also are the well-connected Lt General (r) Muhammad Afzal, the Executive Chairman of TAG, and a third co-founder by the name of Alexandar Lukianchuk. Throw into the mix an inquiry by the central bank, accusations of syphoning company money being hurled indiscriminately by both sides, and open letters being written to investors and you have a recipe for disaster. In short, it is a train-wreck. It is a dumpster fire. It is a fiery trainwreck rattling around inside an industrial sized dumpster fire. And to understand it, we must go back to the origins of TAG, the fintech startup scene in Pakistan, and why buying a bank is such a game changer.

Advertisement

So you want to buy a bank …

TAG must really have wanted to buy Samba Bank to risk sending a forged document to the SBP. The reality is, if an EMI like TAG manages to get a banking licence it will give them a major advantage over the

This email was sent by a disgruntled employee, Ahsan Kaleem Khan who was fired for a number of reasons. He misrepresented that he is no longer a government servant and could not be employed at TAG

Talal Ahmad Gondal, Founder, TAG

competition.

And of course, TAG needed that advantage because they had been falling behind their competition. Initially, TAG had made a pretty big splash when it first came onto the scene, with investors like Fatima Gobi Ventures part of its seed rounds and very early pilot approval from the SBP.

In fact, when TAG got in-principle approval in November 2020, it was one of the earliest EMIs to get pilot approval from the SBP. To the extent that industry insiders said TAG had managed to get pilot approval a little too quickly — almost fishily so.

Rumours began to circulate that Talal had used political connections to get the licence early. You see Talal never quite fit the mould of most Pakistani startup founders. Most founders here are young, American educated, with clipped accents and lofty American ideals.

Talal, on the other hand, has a more desi touch to him. While he is also young and foreign educated, with a degree from Erasmus University in Rotterdam, he is the scion of an old political family from Sargodha. Smart and business savvy, Talal was actually doing pretty well from himself in Europe. He spent a lot of his time in Germany and had a wide network of techie friends, and his first business venture was connecting these techies to recruiters all over the world. He was actually doing pretty well for himself.

But like most startup founders in Pakistan, he had a desire to come back. Except when he returned in 2018, it wasn’t to join the burgeoning startup revolution in Pakistan, it was to run as a candidate for the Punjab Assembly in the upcoming elections. In fact, Talal came back and was briefly awarded the PTI ticket for PP-76 in Sargodha. With slicked back hair, sporting a sharp black moustache in a shalwar kameez and waistcoat, he was a far-cry from the clean-cut, high-paced, and tech centred men and women of the startup scene. But then, political realities meant Talal’s fledgling career as a politician came to a halt. In Sargodha, Talal had managed to get the ticket through his political connections, but part of it was also that he was fighting for a traditionally PML-N seat, which is why the PTI was willing to try a new candidate like Talal. Very close to the election, the ‘electable’ for that constituency that used to run for the seat switched sides and abandoned the PML-N for the PTI. Talal’s near confirmed ticket for the PP-76 seat went out the window, and he now found himself without a political career for the next few years.

The proud Farzand-e-Sargodha had left his work in Europe for a career and politics and found himself out of the loop. But remember, he still had a network of techie friends all over the world. He spent some time in the United States and then went back to Germany and with their help, the idea for TAG began to take shape in his head.

In his mission he also involved Ahsan Kaleem Khan, a close friend from back when they were schoolboys, as well as Ahsan’s brother Tayyab Kaleem Khan, who Talal was friends with as well. Talal began assembling a highly paid team for TAG, along the way they also hired Lt General (r) Muhammad Afzal, who later served as the governing officer for TAG and came with a long list of connections.

These connections were very important. While TAG and other fintech players might be doing advanced, tech based work, they are still very much doing it in Pakistan’s regulatory framework. That means you need people with experience and connections to both help navigate the environment and grease the wheels when necessary. Talal already had political clout, and on top of that he also had military connections within his family as well as in his company. That is where the original whispers also arose that TAG used political connections to secure their approvals from the SBP.

And that is where the bank comes in. As we’ve mentioned before, while they managed to get their approvals early, TAG was falling behind the other players in the market. In September 2021, Nayapay became the first EMI to be granted a licence by the SBP. On

the 21st of December 2021, TAG’s main rival, Sadapay, also gained pilot approval from the SBP. TAG had also raised upwards of $12 million in September that year, but Talal quickly began to feel that TAG needed an edge over its competitors to wipe them out early in the game.

The fintech space in Pakistan has taken off quite remarkably in the past few years, and that has given birth to a number of competing startups like Sadapay, Nayapay, and TAG. Most senior executives have been of the opinion that the Pakistani market is big enough for multiple players because of how largely unbanked the country is. Despite this, the competitiveness between fintech startups has always been high intensity and the players involved, TAG included, haven’t always played nice.

TAG felt that if they got a bank in their portfolio, they would be able to use its licence to enhance their product. It is a concept that has existed within Pakistan’s banking industry for a while. HBL, Pakistan’s largest bank, went so far as to say their goal in the near future is to become ‘a technology company with a banking licence.’

TAG thought, as other tech focused startups do, that they already had the technology and just needed approved channels such as a banking licence and the backing of the SBP. Samba Bank has a record of being a clean bank but it is also the smallest bank in Pakistan. While more traditional buyers like Meezan or UBL wanted it to expand their portfolios, an entity like TAG buying it was simply for its licence.

A commercial bank backing a fintech company could be hugely beneficial for that fintech company. The EMIs are allowed to not just facilitate money transfers between two parties but also to store money electronically into their user accounts. But regulations prevent EMIs from lending from their deposits which means that they are only building a payments business. To be able to lend from their deposits, EMIs can either get an NBFC licence or partner with a bank to build credit products and then distribute them through EMIs digital presence. To be clear, the EMI TAG could not buy a bank. It’s the group behind the EMI that would have bought a bank and then used its licence for the benefit of the EMI.

As an EMI, the cost of borrowing funds from partner banks for lending is also high and the EMI needs to make more than the said cost of funds to turn profits. With a bank on the back, that cost of funds drops substantially because the bank can lend from its own deposits and therefore the cost of funds for the EMI is also very low, which can turn into better profits.

Furthermore, there are deposit and

We have observed that due to increased competition and to access venture capital funding, some companies enter into malpractices and behaviour that would not be becoming of them. It is one of the areas that we have been reviewing carefully and is a concern for us

Reza Baqir, as SBP Governor in Dec 2021

withdrawal limits on EMI wallets. In terms of putting money into a digital wallet run by EMI, the cap is Rs 50,000 in a month, which can be increased to Rs 200,000 provided the wallet holder has completed biometric verification. As far as withdrawals are concerned, the limit is Rs 10,000 per day, no matter what level of authentication has been completed. For commercial banks, once biometric verification of a client is done, there is virtually no limit on deposits or withdrawals.

Once the bank is acquired, the EMI can eliminate the hurdle of limits by moving its operations under the banking licence.

The other alternative to this arrangement is getting a digital banking licence to perform the functions of a bank. However, despite regulations being in place, the competition for a digital banking licence is very high with big commercial banks like HBL and foreign entities in the running for the same licence which would be issued to only a limited number by the SBP (5 in this year). So chances that an EMI like TAG would be able to get a digital banking licence quickly are slim while a shot at buying a commercial bank looks more doable..

All of this means that if TAG, or for that matter any other fintech startup, managed to acquire a bank they would be able to use that bank’s licence to give their product a huge edge. Buying Samba Bank would have wiped the floor with the competition. The acquisition, however, was going to be an expensive one, and TAG needed to show that they were good for the money.

Read more: Should the fintech playbook scare the banks?

How the tampering played out

In December 2021, TAG rolled up its sleeves and decided to put up a bid to acquire Saudi Arabia’s largest corporate lender National Commercial Bank’s (NCB) stake in SAMBA Bank. The interested parties would be able to buy the stake in SAMBA Bank at an estimated value of $100 million.

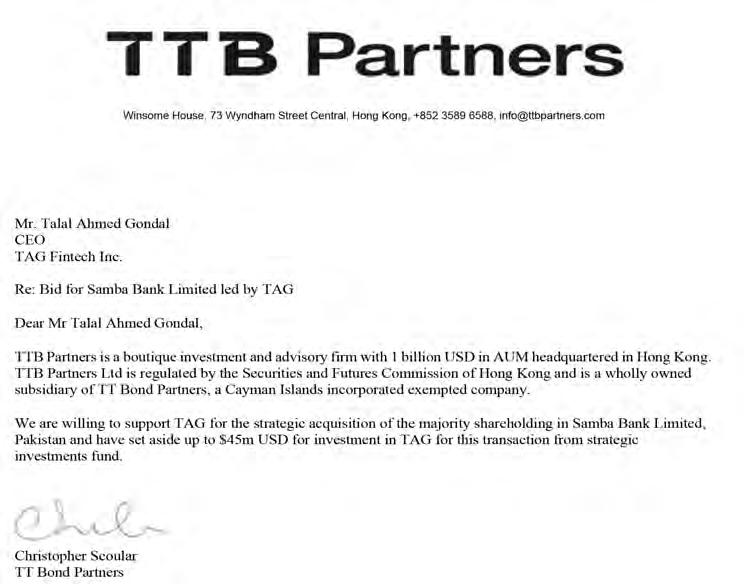

The problem was TAG did not have enough money on its own to buy the bank, despite their recent seed round. That is when TAG decided they would form a consortium to buy Samba Bank. On the 9th of December 2021, Talal sent an email to the SBP saying that TAG Fintech along with Descon Pvt Limited, and TTB Partners were forming a consortium to do due diligence about acquiring a majority stake in Samba Bank. There are two important things here. The first is that TAG Fintech is the Delaware registered holding company that owns TAG Innovations which is the operating company based in Pakistan. The second is TTB Partners — a Hong Kong Based investment firm was in fact part of their consortium. The letter was signed by Talal from TAG (who signed it as CEO of both TAG Fintech and TAG Innovations), and by Chris Scoular of TTB Partners. To prove to the SBP that they were in fact a serious buyer, on the 23rd of February 2022, just in time to meet the deadline to submit the supporting documents, TAG sent SBP a letter written by Hong Kong-based investment firm TTB Partners, and signed by TTB partner Christopher Scoular. “We are willing to support TAG for the strategic acquisition of the majority shareholding in Samba Bank Limited, Pakistan and have set aside up to $45m USD for investment in TAG for this transaction from the strategic investments fund,” reads the letter. Here’s the catch however — that letter was doctored. TTB had never committed an amount and had only shown commitment in joining the SAMBA acquisition bid. The not-so-little $45 million detail had been added to the letter later. Whether it was out of the last minute pressure to meet the SBP’s requirements or the desire to stay ahead of the others, TAG had forged the letter. At the moment the thought was that the TTB would come around and when it did the whole matter would be buried under paperwork, except the lie was caught out.

TTB Partners has not responded to Profit’s request for comments.

Suddenly TAG was in trouble. What seemed in a moment like one small mistake was about to uproot the startup’s entire existence. Falling behind their competitors in the fintech race, TAG had pinned a lot of their hopes on adding a licensed bank to their portfolio — something that would give them a massive edge over other fintech startups. The document was submitted in what was a bit of a desperate attempt to to accelerate the Samba Bank deal.

Apparently SBP did not notice the forgery at first, but Talal’s co-founders and board members did. Ahsan Khan confronted Talal over the forged document. On the 1st of March, Ahsan made Talal sign a written affidavit admitting to the massive mess-up which also served as Talal’s resignation. In the attested and signed confessional statement seen by Profit, Talal admitted responsibility for these actions and declared that it was solely his own responsibility. He did not, however, admit to sending the letter himself, he simply admitted that as CEO it was his oversight and he was taking responsibility for his unintentional actions as a leader. That is where a very tumultuous month for TAG began.

Oh you weren’t supposed to do that …

This is where it gets really messy — the fallout. Because let’s be real, the move was an incredibly stupid one. Talal has at different points blamed his advisors and partner Ahsan for it and admitted that it was a major oversight on his part but has denied malice.

Two of the advisors have denied involvement in whatever happened at TAG, and one even wrote a letter to the State Bank saying that they were never officially appointed by TAG. In fact, both these advisors, in background conversations with Profit, vouch even for each other that they were not involved in this fiasco in any way.

What happened within the TAG

management, however, caused a month of major confusion in the company. On the 1st of March, Talal had already resigned in the affidavit. According to Talal, the understanding between him and Ahsan was that this was a fail safe measure. He claims the affidavit was signed so that in case the SBP found out about the tampering, TAG would be able to say that it was a minor mistake over which their CEO had already resigned. Talal was under the impression that the SBP would not find out and he would be back in the CEO’s chair within a couple weeks without anyone being the wiser.

After taking over as interim CEO, Tayyab and his brother Ahsan began to worry about the danger of the SBP finding out and coming out against TAG, all guns blazing. With Talal out of the picture, Ahsan and General Ahsan began discussing prudent measures to get out of the problem. Both of them felt that instead of risking the SBP finding out, they should come clean to the central bank and let them know what Talal had done — sacrificing him in the process.

On the 17th of March, Lt General (r) Muhammad Afzal in his capacity as Executive Chairman of TAG wrote a letter to the SBP in which TAG withdrew its request to acquire Samba Bank. In the letter, he explained to the SBP that a tampered document had been shared with the central bank, and upon discovery of this a board inquiry had followed as a result of which their CEO Talal Gondal had resigned. A new CEO had been appointed — Ahsan Khan’s brother Tayyab. Meanwhile, Ahsan Khan would continue to serve as COO.

Talal’s great return

To recap, TAG had sent a tampered letter to the SBP, after which an internal decision within major company officials had ended in Talal Gondal resigning. Then, the new management went to the SBP and tattled on Talal. On the one hand, Ahsan seemed to be flanked by the extremely influential Lt General (r) Muhammad Afzal who was the company’s governing officer. At the same time, Ahsan and Talal also had a third co-founder — the German CTO of TAG Alexander Lukianchuk. Alexander sided with Talal, and things at TAG were far from settled.

Both sides had a point here. On the one hand, Talal claimed that the resignation was a small matter and that the SBP might never have found out what had happened and that Ahsan went back on their agreement. On the other hand, Ahsan felt that he would be risking the entire company by protecting Talal. After telling the SBP what had happened, Ahsan began to work towards ridding TAG of Talal entirely. Ahsan approached Talal to try and have him give up his shareholding in the company. In an effort to dilute Talal’s majority ownership, he was asked to give up 10% of his equity in the company and the said shares will be distributed towards company employees under ESOP (employee stock option plans). This would mean Talal would no longer be able to run the show as the majority shareholder.

Up until this point, Talal had not thought there would be any question of him being thrown out of his own company. But he

was not ready to go down. Remember, he still owned a 55% share in TAG Fintech, which is the Delaware based holding company that owns TAG Innovations which operates in Pakistan. Sensing his opponents were on the attack, Talal countered. He lobbied heavily through his family connections and eventually regained the support of General Afzal as well.

Suddenly, Ahsan’s brief revolution was over. On the 1st of April, exactly a month after Talal had resigned as CEO, Ahsan resigned as COO of TAG. His brother, who never really took over as CEO, was also replaced by General Afzal as the CEO of TAG Innovation. Meanwhile, Talal let Alexander take over as CEO of TAG Fintech in Delaware. While Talal does not have an official title at TAG other than founder and majority shareholder, he seems to be now back in the driving seat while Ahsan has been kicked to the curb alone.

In conversations with Profit, Talal has expressed that he was taken out of his role as CEO for something that could have been resolved within the company itself. There is a clear indication that he feels scapegoated over the forged document. There is a certain degree of truth to this, particularly since Ahsan and General Afzal did consolidate control over TAG in the immediate aftermath of Talal’s exit, and Talal had to claw his way back into the company that bears his initials as its name.

However, at the end of the day the mistake was Talal’s. And even if they got some gain out of it, going to the SBP was a prudent decision. Remember Samba Bank was still up for sale and the SBP was keeping a close eye on it. If they had discovered the discrepancy on their own, it would have been a landmine for TAG. Instead, Ahsan and General Afzal decided going to the SBP, admitting everything, and then withdrawing from the race to buy Samba Bank would get them some brownie points.

Even if Ahsan had not gone to the SBP, the central bank would most likely have sniffed out the forgery. Forgery is a serious offence that the SBP, being a regulator, would never overlook. Especially since the SBP has been keeping a very keen eye on every single move being made by fintech startups. In a statement in December 2021, then central bank governor Reza Baqir had also pointed towards this.

“I want to emphasise the market conduct of new tech companies venturing into the payments space in Pakistan, especially with regards to market assessment and practices. We have observed that due to increased competition and to access venture capital funding, some companies enter into malpractices and behaviour that would not be becoming of them,” he said, going on to emphasise that this area because “it is one of the areas that we have been reviewing carefully and is a concern for us.”

On top of this, in his ambition Talal may have forgotten that the SBP would have an extra close on him and his startup, since Talal did not have a clean history with disclosing investments and what he told to investors. In fact, an earlier article by Profit into TAG’s realities was discussed at length in official SBP meetings. Talal had also gotten in a bit of trouble over misrepresentation. According to our sources, Talal claimed that one of the prominent American VCs had joined TAG’s round, and added them to his list of investors. However, it turned out that the VC had never invested in TAG and in fact it was just one partner at the firm that had invested using a special purpose vehicle. It was not the fund that invested itself. So him saying that on his press release was a lie and the VC was very upset with him about it, even though they never went public to rectify this.

In fact the State Bank on its own also verified with TTB Partners the authenticity of the document and learned directly as well that it was not what TTB had committed.

With all of this going on, it was no surprise that the SBP took exception to the forging attempt and on April 11th stopped TAG from growing it’s EMI pilot operations any further. This, at a time when TAG’s competitors such as Sadapay and Nayapay have gotten their full licences and are scaling their operations.

It was obvious that Talal had messed up, and that if no action was taken, it would look bad on the governance at TAG Pakistan which could compromise the chances of getting the EMI licence for TAG. And if the person responsible for the act was not identified and sidelined from the company, it would look bad overall on the entire management and the company itself.

So it was either save the company in which millions of dollars had been pumped and get the long-awaited commercial licence, or save the person allegedly responsible for forging the document. Because if the responsibility is fixed, the board and the management acted prudently and the SBP would then look kindly to the startup for the licence, instead of if it found out that official documents had been forged and submitted to the central bank but nothing had been done about it at the company.

Honey, not in front of the investors …

Another recap: After resigning as CEO, Talal Ahmad Gondal began to feel that his childhood friend and partner Ahsan Khan was trying to force him out of the company he owned. Talal retaliated and ousted Ahsan from his position as COO in the company, but not before Ahsan managed to tell the SBP about Talal’s actions.

The SBP responded by suspending TAG’s pilot operations as well. While Talal had agreed to stay away from TAG, he went back on his word despite him accepting responsibility for the tampered documents going through. Even though he may not have the title of CEO and Director, Talal still has all the power as majority shareholder. So if you are in Ahsan Khan’s position, what do you do? You go to the investors.

This is where the infamous letter comes in. Yes, if you’re keyed into the startup or fintech ecosystem in Pakistan, you will already have received it on Whatsapp by now. On June 16th, Ahsan Khan decided to write a letter to investors to appraise them of TAG’s situation, and give them the bad news that TAG’s pilot operations had been suspended by the SBP. And that the central character who was single handedly running his own company to the ground was Talal Ahmed Gondal.

In the letter, Ahsan spilled the beans to all of TAG’s investors. He explained how

Talal had allegedly submitted a forged document to the SBP affirming that TAG had the backing of TTB Partners which had committed $45 million to acquire Samba. He also told them that Talal had agreed to step down, but had backtracked on the agreement.

Talal’s change of heart became a major sticking point in an already messy situation for TAG. Not only does he want to maintain his control over TAG, along with Alexander he wants to take Ahsan to task for asking him to resign in the first place. According to the letter written to investors and available to us, Ahsan alleges that both Talal and Alexander together conspired against him in an attempt to oust him as stockholder in TAG Fintech, and illegally acted to cancel his shareholding, which according to Talal is only 12%, on fabricated grounds.

The grounds on which Talal and Alexander are acting against Ahsan is that Ahsan misappropriated funds from the company, a charge that Ahsan denies stating that only Talal was the sole operator of TAG Fintech bank accounts and for TAG Innovation, he had the authorisation to authorise payments as per operational requirements of the company such as disbursement of salaries. On the other hand, Ahsan alleges in the letter that it was actually Talal who misappropriated investor funds in the company and transferred them into his own account.

According to the letter, On March 1, on the day Talal resigned, and on March 2, by virtue of him being the sole operator of bank accounts, Talal withdrew investor money illegally in excess of $599,000 from the bank account of TAG Fintech and transferred the same to his personal account. “It is an alarming state of affairs indeed that, to date, Talal Ahmed Gondal took out $1,000,000+ in the aggregate,” Ahsan wrote in the letter to investors.

Similarly, an amount of $150,000 was withdrawn by Talal from operating company TAG Innovation Private Limited “without a bonafide purpose or reason.”

In response, Talal also went directly to the investors just as Ahsan had. In his detailed email, Talal says that all the allegations and the supporting documents provided by Ahsan are mostly fake documents — ironic considering the biggest issue in all of this was a fake document. Talal also alleged that besides misappropriating company funds, Ahsan misrepresented that he was no longer a government employee, which explained his lack of commitment to TAG, and was one of the reasons that he was fired from TAG.

“He was given an opportunity to return the funds and when he did not on time, upon advice of our counsel, Ahsan’s shareholding was suspended and cancelled,” Talal wrote to investors in response to Ahsan’s letter. “This email was sent by a disgruntled employee, Ahsan Kaleem Khan who was fired for a number of reasons. He misrepresented that he is no longer a government servant and could not be employed at TAG. He is back at his public sector job. This surfaced in the audit. This also explained his lack of commitment to TAG. He also made unauthorised withdrawals from the company accounts.”

What next …

As things stand, TAG is still operational. According to officials from TAG, the SBP has already conducted an audit which has come out clear and that they are on track to get their EMI licence. While it has not caused any immediate lasting damage to the financials of TAG, the entire incident will leave a bad impression on investors.

According to Talal, well, besides one rogue employee, all is well. That the company is burning only $350,000-400,000 per month and they have enough money to last for more than a year. That the company is making advancements on the product and technology side and it is only the SBP approval that they are awaiting.

Talal Gondal still controls the majority shares in TAG Innovate Pakistan’s holding company TAG Fintech, and even though he is not the CEO he can still exercise the most degree of control on the company as the majority shareholder. Ahsan has allegedly made overtures towards acquiring Talal’s shares but have been rebuffed. At the same time, Ahsan has resigned from his position as COO and instead now Talal is attempting to take away his shareholding in the company. With letters and emails going back and forth directly to investors, things might not be a complete disaster at TAG but the situation is less than ideal and conducive to focusing on the product.

While the big dogs at TAG fight it out, the company and its financials will suffer. As of now, it is only Talal Gondal that is under serious scrutiny by the SBP and it is him that the show cause notice of the SBP was directed towards. However, he is still steering the ship even if he is no longer officially the captain because, well, he owns the ship.

It is unlikely, however, that in the middle of all of this TAG’s operations will not be affected. While sources close to TAG claim that things have settled down now, and SBP after imposing a fine, will grant TAG the full licence within the next few weeks, this entire episode will leave a bitter aftertaste not just for the SBP, but also for TAG’s investors who have gotten a front seat to the row between Talal and Ahsan. What this will mean in the long run is anybody’s guess. The final verdict on the extent of damage to TAG from this is going to be given by the SBP, which as of this point in time, is still in the process of deciding on TAG’s future and that of Talal.

The SBP has not disclosed details about TAG in request for comments by Profit. n

Additional reporting by Abdullah Niazi, Ariba Shahid and Babar Nizami