12 minute read

Under a new rule, the PTA seeks total internet control

Adigital dictatorship could be coming. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) is moving ahead with implementing a policy that will give them complete control over who can see what on the internet, and in getting this control, they might break the internet altogether across the country.

Advertisement

The PTA is the de-facto authority in Pakistan which controls which websites can and cannot be accessed from Pakistan. It has till now exerted this control by ordering the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block the websites it does not to be accessed from Pakistan through a Centralised Domain Name System (C-DNS). Now, it wants to extend that control and be able to block the websites on its own by taking control over the DNS servers via the C-DNS.

The fact that there is already an effective mechanism through which the government controls which websites can be accessed from Pakistan, puts a question mark on the motives of this policy. The move can curb internet freedom, violate internet privacy of individuals, but most importantly the new system is against the way DNS operates and could actually bring down the internet for everyone in Pakistan.

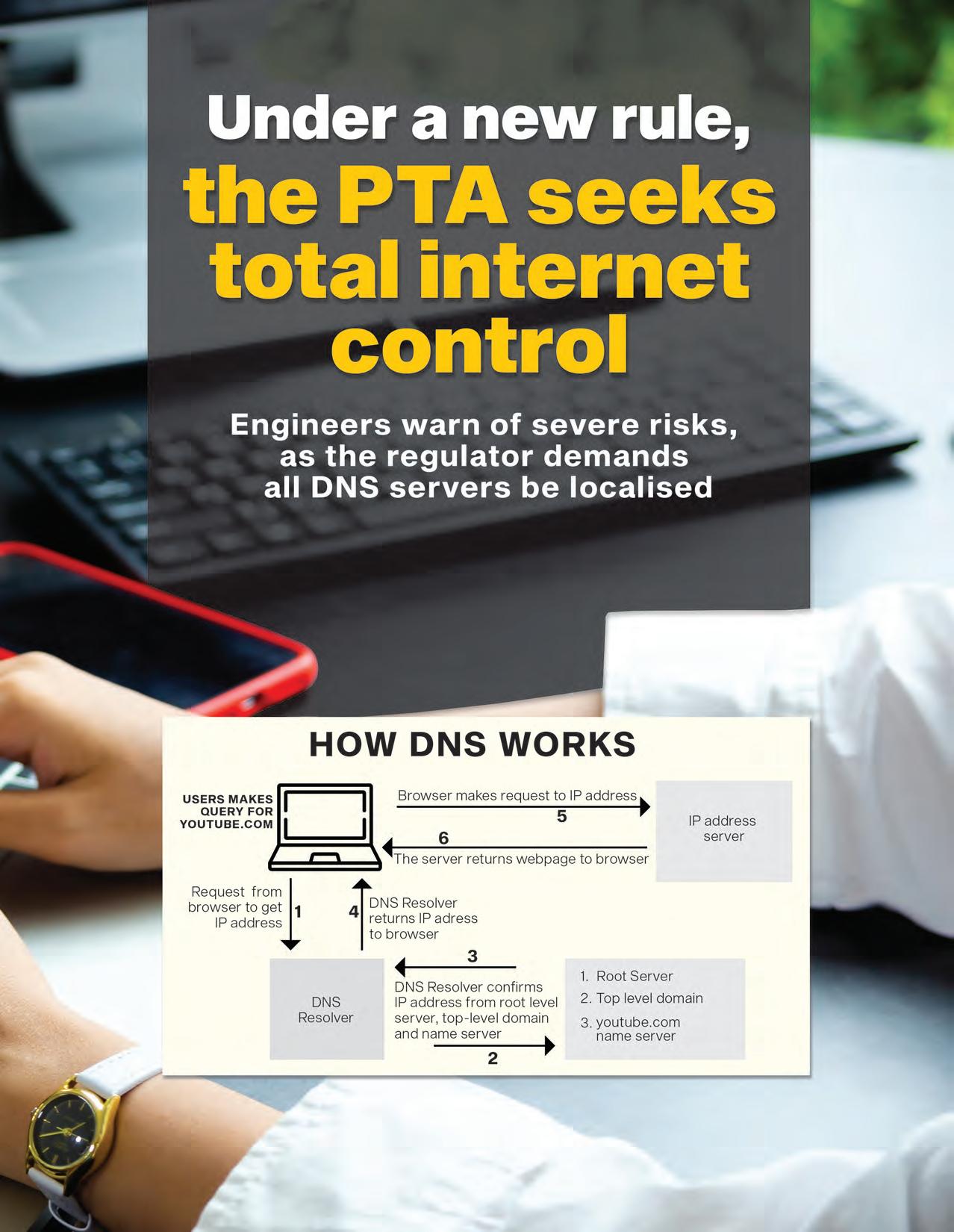

To understand what the government plans to do and how it plans to do, it is imperative to understand how DNS works.

What is PTA aiming to do with DNS?

So if some website has to be blocked in Pakistan, all that any ISP has to do is put the URL of the website that needs to be blocked in the DNS server and stop the DNS from getting the IP address for that website. So for instance, if your ISP blocks Facebook.com, when you search for Facebook.com on your browser, the DNS would simply not lookup for IP address against Facebook.com domain name. And if your browser does not get any IP address, it won’t be able to retrieve any webpage with that name. This is quite simply how blocking of pornography websites is being done in Pakistan right now - at the DNS level. The PTA has a list of websites that they have declared as illegal and do not want users here to have access to. There is a blanket ban on accessing pornography websites from Pakistan and the government implements this ban by asking the ISPs to block such illegal websites at the DNS level. The PTA itself provides the list of URLs of such sites to be blocked.

The PTA currently does this blocking through the CDNS (or C-DNS/Centralized DNS), which is a supervising automation tool for domain blocking to control illegal content. It is managed by the PTA and integrated with DNS servers of operators/ISPs through APIs. This API provides a platform for pushing single/multiple website URLs for blocking and unblocking with internet service providers in Pakistan.

All PTA has to do is it pushes the URLs of pornography websites from its CDNS onto the DNS servers of operators and ISPs. Once these websites are recognised for blocking, the DNS stops looking for IP addresses of these websites.

The PTA really has this ability to control the internet right now and block any website that they declare as illegal, and ISPs have to abide by what the PTA asks them to do as part of their licensing requirement.

The PTA now is asking for more control over the internet by directly controlling the DNS. And they are doing this under the pretext of policing illegal content, over which they already have effective control. Under the new policy, the PTA has asked all the ISPs in the country to connect with one single centralized DNS server through which all the DNS lookups would go through. “The ISPs have been asked to stop routing requests for any DNS in the country. They have to stop routing any requests for DNS lookups outside the country, or to anybody else. There should be one centralised server in the country where every ISP routes all DNS lookups,” said an official from a top tech company.

Under this new policy, whenever anyone searches for any website name, the CDNS is where the DNS lookups to retrieve IP addresses will happen. So if you are a PTCL user and you search for Facebook.com on your internet browser, the search on the DNS will go to your ISP which will route it to the CDNS, which will retrieve the Facebook.com IP address against your search. Similar process will follow for users of other ISPs like Nayatel, Cybernet or Multinet.

Because it is the centralised DNS controlled by the government where all the searches are going, the government would be able to do DNS level blocking on its own, without distributing any URLs to ISPs for blocking. So if the government wants to ban Youtube.com tomorrow, the CDNS would simply refuse to get IP addresses for Youtube.com for all of Pakistan’s internet users, whenever they search for Youtube.com on whichever internet provider’s service. This higher control comes with different levels of consequences though.

Engineers and officials from a big tech company, in a deep background conversation with Profit, warned of the dangers of such a system. “One entity knows every single [website] name a user has searched for. So you are trusting that whoever is running that [centralised] server, isn’t using it in a nefarious way. Because now every endpoint that is using that [IP address] lookup, that person knows what name did you ask for in the address book,” says a network engineer from a top tech company.

While internet privacy is a strong concern because one single entity would have access to search records of each user, more importantly, such arrangement runs the hazard of breaking the distributed nature of DNS servers and could lead to internet winters across the country.

“If you decide that you dictate what DNS server address everyone should use, and that is one centrally controlled server, the first big concern is reliability because what you have now done is that there is just this one place, which maybe has a primary or secondary address, that you can go to look up an address book,” the tech engineer said. “This raises the risk of overloading the system. If someone has nefarious intentions, they know they have to take down just two or three IP addresses in the country and that will break DNS for the entire country.”

“So reliability, privacy and security are the main concerns,” he says.

The caveat here is that if an authority dictates which DNS server address everyone should use, all the searches would now be directed to a single centralised server which could overload the system and lead to an internet slowdown for everyone. In fact, if anyone wanted to take down the entire internet in Pakistan, they could send fake queries in big numbers to this server, overloading it and bringing down the internet for everyone.

When it is distributed, users of different ISPs are using various servers of ISPs for internet searches, balancing out the load to many such servers.

The centralised DNS server would also have an IP address of its own and one or two backup IP addresses. If someone with heinous intentions planned to take down the entire internet for Pakistan, they could just attack the centralized DNS server and would have to take down just two or three IP addresses, which will again breakdown DNS for the entire country resulting in internet outage for everyone.

All of the internet users, have at some point in time, faced internet outage. Maybe because the DNS of their provider broke down, or because of some other issue. But these outages would most likely have been restricted to individual ISPs, unless it was

a country level breakdown for all due to some reason. The situation at present is that because each user is connected with the DNS of their respective ISP, any problem with their DNS would not affect users of the other ISP. For instance, PTCL users may face a service outage because PTCL’s DNS service broke down but other ISPs users would be surfing the internet just fine.

That is because their networks are different and their DNS servers are different. One ISP’s trouble in DNS servers does not affect the others. But once DNS is centralized under the new regime, because all the lookups will be happening through the central server, any breakdown of DNS at the centralized server means no internet for anyone.

In another scenario where the CDNS is unaffected, but the network supporting the CDNS runs into some problem, the internet for all would still be down, even though the individual ISPs would have no problems in their networks and systems. This is the third major problem with centralizing the DNS arrangement. That because it sits on a single network, any trouble with this network would mean that every other network that is relying on the CDNS system for reachability to the internet, may also be broken. Hence internet outage again for the entire country.

The situation again becomes where all other ISPs are providing service seamlessly but a single problem with the network at CDNS makes everyone lose access to internet. If users of different internet service providers are not able to reach the phonebook (meaning they are not able to lookup and get IP addresses for the searches they make on the internet through the DNS), they search at the CDNS because of some issue with the network, access to everyone is interrupted because there is only one server carrying out these operations.

Because of these reasons, it is important that the DNS is available at many places. By allowing them to be redistributed, it allows the internet as a distributed infrastructure to actually function. And if it is centralized, all the users get affected.

The magnitude of the impact centralizing this arrangement is horrendous. It affects all the internet users in Pakistan simultaneously, and impacts all the ISPs, too, simultaneously. These ISPs have made expensive investments to set up these DNS servers so that internet goes up and running seamlessly for their users, which they would have to see going to waste.

It is not only the websites that would be impacted. Some of the mobile applications have IP addresses hardcoded into them. So if a website is blocked on the CDNS, if its IP is being used by mobile apps, those apps would also stop functioning. For instance Google apps on your phone.

On the other hand, some ISPs do argue that it is a Sovereign’s right to implement policies to exercise its right as a Sovereign. Every state has national interests and if there is some content on internet that is against the interest of the state, they have the right to block it. The usual course of such blocking is to request the platform, say YouTube, to take down anti-state content.

Now YouTube might have its own policies and might not cater to the request of a Sovereign state, in which case, the state needs to have some mechanism in place to block content not favorable to the state.

“A country should have the ability to block off a website, complete end to end, if the social media site does not have the ability to respond very quickly to a country’s request. The social media site should do that. In case it does not, then a Sovereign might want to block it altogether,” said an official from a

What is DNS?

Every time you enter a website name on the internet, for instance Facebook.com, this search query goes to a DNS server operated by your internet service provider (ISP). The DNS is responsible for taking that name and matching that to an IP address for that website address.

Think of DNS as a phonebook for the internet which has information on IP addresses associated with the billions of domain names on the internet. Each unique domain name would have one or more IP addresses associated with it. Just like in real life phonebooks you can look up for phone number(s) of individuals, DNS is where these phone numbers of websites translated into their IP addresses could be looked up.

So when you put up a search for Facebook.com, the DNS would look up for the IP address for the server hosting Facebook.com, and let the browser at your computer know that this IP address is where Facebook.com could be accessed. The browser then sends a connection request to that IP address to retrieve the Facebook.com webpage.

While users enter website names, at the back, internet routing is taking place on the basis of IP addresses. It is only for the convenience of users so that they don’t have to remember IP addresses for websites that these IP addresses are converted into and searched as website names. Just like phone numbers for people, websites can have multiple IP addresses. It is the DNS that identifies which IP address to look for, and what the other IP addresses are in case one of the IP addresses is down.

“That is all the DNS does. It is a globally distributed internet phonebook. It says that every name on the internet can only be reached by having a phone number. In the internet terms, that phone number is an IP address,” said a network engineer at one of the big technology companies, during a deep background conversation with Profit.

Users can access websites directly as well by putting IP addresses of the servers hosting these websites, in which case DNS is not involved. But a majority of people would not know what the IP address of the website they are searching for is. Even if they did know, they would not be able to remember it, or wouldn’t be able to remember many IP addresses at the same time. Think about a situation where you have to remember a twelve digit number each for Youtube, Facebook, Google and Netflix, and use that number each time you want to access one of these sites. It is going to be painful.

All major internet service providers in Pakistan have their own DNS servers which check if the IP address of the website a user has searched for is the latest one or not, and then direct the user to that IP address.

Different ISPs have their own DNS servers that give the DNS a distributed nature. So if PTCL’s DNS server is not working, it will not affect users of another ISP.

local ISP in a deep background conversation with Profit.

Speaking to Profit, official from another internet service provider likened it to “halting the entire traffic on the road just to stop one car.” Then again, blocking some websites does not seem like a motive of this move to many. As mentioned earlier, the PTA already has mechanism in place through which it can block any website even right now.

Profit reached out to Mukarram Khan, director general of Cyber Vigilance Division (CVD) of the PTA, to learn about the ins and outs of the policy from a PTA perspective. The DG asked Profit to contact their spokesperson for comments. Khurram Ali, PTA spokesperson, was contacted who also refused to comment on the phone call with him, and asked for questions to be emailed to him. The queries were posted to him via email. No response has yet been received from PTA to those queries. n