14 minute read

The ‘bold’ economic demands of the Aurat March

The march commands great public interest. It is using it to advocate for the economic rights of women and marginalised groups

By Zunairah Qureshi

Advertisement

In 2018, the Aurat March was conceived as a concept for women looking to reclaim public space on the occasion of women’s day by organising a march. The idea resonated, and over the past four years the march has grown from a loose association of feminists into an organisation that advocates for progressive politics in Pakistan. Why is Profit talking about the Aurat March? Because it is currently perhaps one of the most significant organisations that commands increasing public attention with every passing year. Whether it is the cesspool of Facebook and Youtube based media ‘organisation’ that hound the march every year or the thousands of people that attend the event every year, the Aurat March has managed to get conversations started on taboo subjects - something that could not have been dreamed off a few years ago. Using the momentum of the spotlight, the march has in years past and in this year in particular advocated for the economic rights of women. The Aurat March is a decentralised organisation. It is not a political party, it is not a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO), and it is not a charity. The marches each year are organised by volunteers, and a large cross-section comes up with the manifestos for each year. This year, there has been a perceptible shift in demands that were, in earlier marches, more focused on women’s protection against harassment and violence to the realisation of their economic rights. This year’s march’s theme is best encapsulated in its slogan, ‘ek hi nara, ek hi junoon // ujrat, tahaffuz, aur sukoon’ (one slogan, one passion - wages, security, and peace).

Demands were made for recognition of labour carried out by homemakers and caregivers through a substantial living wage or basic universal income under social security. The lack of enforcement of labour laws and minimum wage for domestic workers and other women in the informal labour force were other issues raised. Moreover, IMF-backed policy changes like the excessive privatisation of large-scale industries employing large numbers of low-income workers and increasing taxes were protested against for being ‘anti-poor’ in nature.

The Aurat March’s mission and demands can be found in detail in their manifesto and charter which are available both in English and Urdu. It is clear that the march cannot be mistaken as a one-day jubilant affair but has come to stand as a political force that is likely pivotal for the country’s social as well as economic structure. So, we need to talk about the women’s movement because it cannot be ignored or fluffed aside any longer.

What is the Aurat March?

It all started in 2018 with a group of activists, members from concerned organisations, and others committed to the cause. The march started as a way to reclaim space for women and provide a platform for expression and to voice demands. In five years, the march has grown from a congregation of 5000 people in 2018 to 10,000 plus in Karachi alone. That is perhaps the most important part about the march - it is a sum of the attendees that make it up. Every banner that is brought in, every poster, every interview given, every slogan chanted - all of them come from women and gender minorities that have found the march to be an outlet for self-expression and have found a voice through it. And while the march has a diverse group of attendees, it has over the years grown into an organisation that can largely be labelled a progressive movement advocating for political and economic policies meant to uplift women and the suffering masses.

The march continues to grow in number and scope in Lahore and Islamabad as well but has also expanded to other cities such as Multan, Hyderabad, and Sukkur. It has also become more inclusive with time as members of various marginalised communities such as transgenders and religious minorities have found a space for themselves at the march.

Pastor Ghazala who has been part of the Aurat March organising team since 2018 pointed out that, ‘Where most women from the Christian community were unwilling to join the march, this year they have come in full buses from nine to ten different areas.’

In Karachi, foreseeing a growing number of participants, the venue was shifted from the Frere Hall park, which is located in an up-scale commercial area to the more communal Jinnah Bagh and this further helped bring together a more diverse community. Pastor Ghazala elaborated, ‘A lot of poor women joined this time as well including domestic workers, sanitary workers, and women who have lost their homes.’

Though the Aurat March has become somewhat of a flagship women’s right movement in recent times, women’s movements and rights activism dates much further back. Dr. Shama Dossa, Associate Professor, Social De-

velopment and Policy at Habib University, who has researched feminist movements in Pakistan and also been part of the organising team of Aurat March 2020 told Profit, ‘There has been no such thing as a ‘rise’ of feminism in Pakistan. It’s nothing new. Muslim, and Sikh women have been fighting for their rights since centuries.’

She further added, ‘Many organisations have been working for women’s rights. For instance, the Women Action Forum has been combating issues such as the zina ordinance since the Zia period. How Aurat March is different is that it has reached out to today’s youth.’

Perhaps it is indeed the attendance of large numbers of young university-going and working women with a fresh approach towards wrestling their rights and bolder visions that makes the Aurat March stand out among other movements.

Dr. Dossa told us that, ‘There are a number of movements, like the homemaker’s movement, the lady health worker’s movement, and the Hari women’s movements. Aurat March cannot equate to the work done by all these movements but it does provide a platform for cross-movement linkages.’ She also added that the march has ties with women’s movements across the border, in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and India, from where activist Arundhati Roy has frequented Pakistan to contribute to the shared cause.

This is visible in the strength and coverage that other movements have derived from the impact of Aurat March as a number of them, like the Home-Based Workers’ Women Federation which has been operating since 2005, also set out on a march this Women’s Day. They demanded recognition and labour rights for women working from home for companies that sell their hard work in the national and international markets for minimal remuneration.

The demand for ‘Ujrat’ and why it is more important now than ever

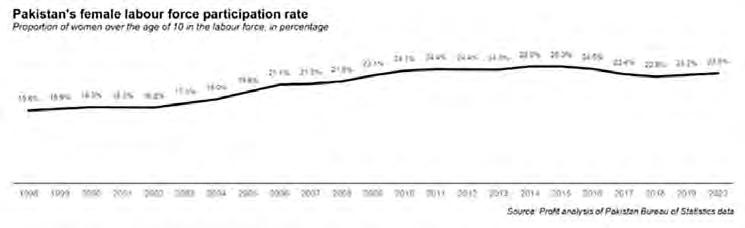

Pakistani women are earning more money, have more disposable income at hand, and have access to social media that helps them discern between low and high quality products. The data on Pakistani women’s rising economic power is staggering. The female labour force participation rate rose from under 16% in 1998 to a peak of 25% in 2015 before declining slightly once again to 22.8% by 2018. That means there are millions of women who are currently working who might not have been, had labour force participation rates for women stayed the same. The total number of women in Pakistan’s labour force – earning a wage outside the home – rose from just 8.2 million women in 1998 to an estimated 23.7 million by 2020, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. That represents an average increase of 4.9% per year compared to an average of just a 2.4% per year increase in the total population. In short, the growth in the number of women entering the labour force is more than twice as high as the total rate of population increase.

All of those women now in the workforce have more purchasing power than ever before. Women have always had some measure of purchasing discretion for their households. But now, with their own incomes, they have more ability than ever before to make discretionary purchases for themselves, rather than just making decisions for their households.

This data means two things - the first is that the number of women in the labour force increasing here is largely the number of women working white-collar jobs. This does not account for either the unpaid labour that women undertake as homemakers, and it also does not include a large number of undocumented women labourers engaged in cottage industries and other sectors like agriculture.

What it does mean, however, is that the trend of women from more affluent middle to upper class backgrounds joining the workforce in droves is that there is more unrest amongst this section of society. And because these women have a voice because of their relatively good position in society, their demands for better working conditions and equality can then reach the most marginalised women in Pakistani society.

The Aurat March at times has been criticised as an ‘elitist’ event - and while it is true that the drivers behind the march are mostly women from solidly upper and upper middle class backgrounds (university goers, working women, etc), the march has also made very concentrated efforts to not just try and bridge that gap but also advocate for the most economically, socially, and politically marginalised segments of society.

It isn’t just about equal wages

Many associate feminism with gender equality, and it is that. But it is also more than that. The economic rights that the Aurat March cries for addresses economic justice as well, such as equal pay for all genders, among many others, but what it really demands is change at the structural level. The Aurat March 2022 manifesto starts off with these words: ‘This year we march for our labor… We march for a living wage. We march for social security…’ In a radical move it calls out the current capitalist system for running on the exploitation of women’s unpaid domestic labour by only remunerating ‘labor that is ‘productive’ or can produce tangible commodities’. Their charter of demands refers to a ‘care economy’ that is based on women’s home-making and care services for their families. While in 2019 the demand was simply for recognition of women’s unpaid ‘care’ labour, in 2022, they proposed the solution of introducing a basic living wage or universal income for the social security of all paid and unpaid workers, whether employed in the formal or informal sectors. Pastor Ghazala told Profit, ‘In the first one to two years of the march, we focused on the issues of harassment, rape, and forced conversion. Then we began to notice the immense exploitation and misery of marginalised communities which is why we worked more for their economic development.’ This year there was a particular focus

on domestic workers and their lack of labour rights. Demands included recognising their labour as legitimate by mandating employment contracts and minimum wage. ‘The minimum wage was set at Rs 25000 by the government (in July 2021) but like other laws, this is not enforced.’

Pastor Ghazala explained further, ‘No one checks if maternity leaves are implemented and women workers are kicked out during their seventh month of pregnancy. Factories employ home-based working women, where the middlemen don’t let them come to the factories and instead treat their work as part informal labour with no rights protection.’

Similarly sanitary workers employed by private companies are underpaid and forced to face severe health hazards when they are not provided safety gear or any kind of equipment to work in sewerage lines, even during the covid-19 pandemic. Lady polio vaccine workers are also exploited and even though these women know their rights are being quashed, they do not have the strength to stand up for themselves.

This is why the Aurat March and associated bodies are essential in highlighting women’s economic labour issues. Safina Javed, a women’s activist and founding member of the Aurat March emphatically declared, ‘Don’t think that Aurat March happens once a year. Our work extends all year round as we lobby for women’s rights.’

The Aurat March is organised by the Siyasi Aurat Tehreek. This group in collaboration with other organsiations, like the Sindh Human Rights Commission, research institutions, and devoted individuals, such as lawyers, work towards solving a multitude of issues by engaging with communities and lobbying the government.

Safina Javed associates the abolishment of the two-finger test in rape cases, and growing awareness among women about their rights against harassment to their efforts and the Aurat March’s success. ‘You can see more cases are being reported. Young girls aren’t as scared anymore. Workplaces and universities have had to put in place sexual harassment laws.’

The Aurat March has been demanding proper implementation of the Protection Against Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2010 for a long time. In the past, they have also pushed for the health budget to be decreased to 5% of the GDP. This year, in addition to the above mentioned, their charter included demands for increased representation of women in trade unions, access to clean air, safe environments, and public spaces, protection of the Transgender Persons Act, and reforms for the justice system among many more.

Women scream for ‘Azadi!’ but what from

It is important to understand that the Aurat March is not just for women. It is for all persons and beings that are ‘under threat by the oppressive system’. This includes the poor, children, religious minorities, transgenders, children, and others. The Aurat March and its affiliated workers stay with the times and recognise systematic modes of exploitation that affect weaker persons in society. One of their most fervent demands calls for the limitation of IMF-backed policies that hit the poor members of society the hardest. According to Safina Javed, ‘Under the oppressive system that we live in, poverty is increasing, upon which more taxes are being placed, and there is no gas or heat. The increase in privatisation of public facilities leaves many unemployed and a lot of the poor class insecure.’ Since the Aurat March is a movement powered by the young, it has a presence that is intermeshed with the social media culture. This also means that it is open to and at the brunt of harsh and many times, plainly obscene responses by all kinds of social media users. This in itself is reflective of a problem women march for. Many male members of society and traditionalists do not understand Aurat March’s main purpose. They choose to troll the march - what is clearly a political movement in its own right – for being something of frivolous showcase.

When a large group of women step out on the roads to speak up for themselves in a conservative society like Pakistan’s, the act in itself is seen as improper and even ‘vulgar’. However, the women persist because they want to be able to walk their own streets safely and reclaim public spaces for themselves.

For the past few years, each International Women’s Day, the Aurat March faces a showdown with the ‘Haya March’ that is led by a group of burqa-clad women from religious political parties. They bear slogans that say, ‘Men and women are not competitors but compatriots,’ showing a deep misunderstanding between the two parties.

In fact, many don’t understand the rights that the Aurat March campaigns for. They question, ‘Why do women need rights when our religion and culture already offer them respect and the rights they deserve?’

The answer is that the Aurat March and its feminist doctrine does not simply ask for one or two rights that are missing or aren’t enforced, instead it recognises the existing system as a problem. It is a socialist movement that does not agree with capitalism to the extent that the organisers told us that they do not take any funding from the corporate sector or sell any sponsorships.

Safina Javed explained to us that, ‘All our funding comes from our own pockets and through fundrasiers.’

Pastor Ghazala was livid when she said that, ‘They (opponents of the march) say we are foreign-funded. But we all have our accounts; can they show us a single rupee that is coming from outside?’

Not everyone will agree with the feminist movement’s socialist ideas. However, it is hard to deny or ignore the fact, as highlighted by the Aurat March, that gender discrimination is a systematic and structural problem.

This is what makes the Aurat March and other bodies like it so relevant. They recognise that many developments and pressing issues like the IMF-sanctioned budget cuts, privatisation programmes, and lack of climate action need to be re-evaluated and revised for its impact on the marginalised communities. n