10 minute read

IMF – Back to square 1

In the last full year of its term, the PTI government has managed to land itself back to the same position it was in at the beginning, back in 2018. Once again they are looking at a severe adjustment to control a ballooning current account deficit, a raft of deeply popular tax measures to shore up the fiscal equation and continued hikes in interest rates to curb inflation. In short, once again they have to apply the brakes to growth in order to manage growing macroeconomic instability, and along the way pay the political price that comes with such measures. Look at the projections for the current account deficit (CAD) in the remaining months of the fiscal year, running from January to June 2022. In line with the State Bank’s projection, the CAD is expected to reach $13 billion by June 2022 according to the IMF. At the same time, gross official reserves stock is expected to hit $21.2bn, when it currently stands at $17.7 (including the one billion dollar each from the IMF tranche and the recent Sukkuk flotation). Now consider this. The CAD has already reached $9bn in the July to December period, meaning it can only rise by another $4bn at best in the remaining months of the fiscal year to remain within the program projection. This means an average monthly CAD of $666 million for the next six months where it has averaged $1.5bn per month so far. How is such a sharp deceleration in the CAD to be achieved? The only way would be through a sharp deceleration in the trade deficit. But the program projects anything but a deceleration. According to the original projection on trade deficit (goods, services and net income) for FY2022 made back last April this deficit was supposed to come in at $34bn by this June. In the projection made in the latest document released on Friday, this amount will be more than $45bn. For the next few years it is projected to remain around this level, meaning the additional import requirement that the economy has added since April last year now has to be carried through more stringent reserve accumulation measures. Perhaps this partly explains the sharp jump in the external financing needs, the near unseemly urgency of the government to borrow (lifting a billion dollars from international markets at exorbitantly high interest rates even before the IMF program had been approved by the board). The government’s stint in power began with the country facing a massive current account deficit and a troubled approach to the IMF for immediate assistance. It took them nine months to get an agreement on a Fund program, and jettison their star finance minister – Asad Umar – along the way. From November 2018, when the negotiations began, till July 2019, when they were concluded with Hafeez Shaikh’s signature, the government cut a difficult path trying to water down the scale of the adjustment the fund was demanding and soften some of the conditions. Nine months later they signed on the dotted line, after removing their finance minister and bringing another one in.

Advertisement

Today they are back to this position all over again. The negotiations for restarting the facility, that was suspended in March 2020 with the arrival of the pandemic and the start of the Covid lockdowns, began in November 2020 and came to a culmination in April 2021 when the program parameters were agreed to and the government gave the commitment that “we are unwinding the Covid crisis related economic stimulus spending measures (1.2 percent of GDP) and freezing non-priority spending”. This was from the Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies submitted by the government to the IMF back in April 2021.

This commitment to unwind the fiscal and monetary stimulus announced in the wake of the pandemic was the core of the Fund program at that time. But the government reneged on its commitment, after obtaining approval from the IMF board, and after receiving the $500 million that was disbursed against it. And just like the beginning, they changed their finance minister. Hafeez Shaikh was out and Shaukat Tarin was brought in his place.

The budget that Tarin announced in June 2021 was supposed to carry a raft of new taxes, remove exemptions and restrain expenditures. By that point the State Bank was supposed to have passed a series of interest rate hikes as well, although the goal of “mildly positive real interest rates” was to be reached gradually, not suddenly.

None of this happened. Instead we had a budget without a credible tax plan and no real expenditure restraints. Weeks after the budget came the announcement of the Kamyan Pakistan program, further adding to the expenditure commitments as if there were no constraints on government resources. That budget, the IMF says, magnified the vulnerabilities and led to a rapid rise in the current account deficit, as well as the external financing requirements for the economy.

“[T]he approved FY 2022 budget marked a departure from EFF objectives and contributed to rapidly increasing macroeconomic vulnerabilities” says the IMF in its accompanying Recent Economic Developments report released on Friday. “It delivered a significant fiscal relaxation through large spending increases and the unwinding of several EFF tax revenue commitments, notwithstanding the past revenue underperformance.”

Even though revenues had underperformed in FY2021, the government powered ahead with further tax breaks and expenditure increases in a desperate bid to boost growth at a time when the economy had not recovered from the adjustment it had embarked upon from July 2019. “On the expenditure side, it allowed for large increases in public wages and allowances, a doubling of subsidies, and an increase in investment of over 50pc” the report says. “On the revenue side, it expected unrealistically strong tax revenue growth (from marked improvements in tax administration and strong domestic demand, notably imports) and high non-tax revenue receipts, thus introducing significant risks of fiscal slippages. In addition, the budget delayed key reforms and reversed some key policies, damaging revenue prospects.”

This is what made the minibudget of January 2022 necessary. All through the months that followed that budget announcement, the government touted the growth of exports. It did not mention, though, that in the course of securing these incremental exports, the external financing requirements of the country rose by $7 billion for FY2022 alone.

Back in April the IMF had projected external financing requirements at $23.6 and $28bn for fiscal years 2022 and 2023 respectively. Those projections have now been raised to $30.4bn and $35bn respectively, and increase of around $7bn per year.

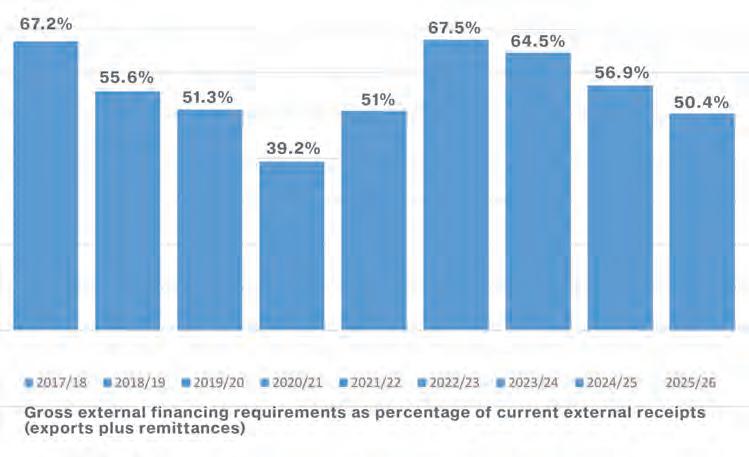

The more meaningful number here is external financing requirement as a proportion of current external receipts – exports plus remittances, since these are the two large dollar earning heads from which Pakistan earns its foreign exchange reserves and services it external debt burden. As the graph shows, external financing requirements reached 67.2pc of current external receipts in the bad old days of FY2018, right before this government came to power. They fell sharply after that as the painful adjustment under the IMF program began in 2019, falling to 39pc by FY2021, but have spiked again and are projected to return to their earlier level by end of next fiscal year. In terms of the economy’s ability to meet its external financing requirements through its own resources, the country has returned to 2018, back when the story began. This is the other side of the coin to the export growth that they tout all the time, and it does not paint an edifying picture, the side they don’t tell us about.

Some realization began to sink in among policy circles that the course of action taken after the budget of June 2021 was not sus-

tainable as far back as September. That was when the State Bank administered the first of its monetary tightening measure, saying “the pace of the economic recovery has exceeded expectations” and led to “a strong pick-up in imports and a rise in the current account deficit.” It announced a small, 25 basis point, hike in the interest rate to “slow the growth in the current account deficit” and shift its focus away from supporting growth towards “tapering the significant monetary stimulus provided over the last 18 months.”

In significant measure their hand had been forced by a strong bout of volatility in the exchange rate all summer, forcing substantial interventions on their part that have now also been acknowledged in the IMF report. This was followed by two extraordinary and hurriedly arranged rate hikes, of another 150bps in November followed weeks later by another 100bps hike in December after which the Governor announced a “pause”.

But now that pause may also need to end, given the challenging external sector requirements shaping up in the remaining six months of the fiscal year. “Staff welcomed the recent policy rate hike” the IMF says in its latest report, “and sees continued monetary tightening critical to support much-needed disinflation.”

This “continued monetary tightening” will have to come about through raises in the interest rate as well as “phasing out various liquidity-enhancing facilities over the medium term”, referring specifically to the raft of refinance facilities the State Bank announced as part of its monetary stimulus in the wake of the pandemic. Gone are the targets for lending to the housing sector, the Ehsaas Emergency Cash assistance program, the refinance facilities and the flush of easy money they brought for industry. Along with this there are upward revisions coming in gas and power prices. Some of the impact of these measures is already programmed into the monetary targets. All the components of broad money show sharp reductions in their growth in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal year – the months running from May to June, pointing towards a rate hike before May.

Keeping exports going in the face of these measures will be a challenge, but any decline in exports earnings will have to be compensated with interest or exchange rate adjustments since borrowing more will no longer be an option to build reserves.

It is for this reason that the budget of fiscal year 2023, to be announced this June, will have to contain further tax measures as well as continued expenditure tightening. FBR revenues are programmed to rise by around Rs1 trillion in the next budget. On the other hand expenditures are projected to rise by Rs613bn, of which Rs500bn is incremental interest expenditure alone. Development spending shows slight declines from current year and defense spending is projected to rise by Rs186bn each year in the next two years, also a very slow pace of increase. The thrust of the program seems to be towards swinging the primary balance from a projected deficit of Rs688bn to a surplus of Rs751bn in one year.

All equations will be extremely tight for the government from this point on, anchored ultimately in exchange rate flexibility, interest rate hikes, strong revenue performance while keeping expenditure firmly under tight limits. The program aims to shore up the country’s debt sustainability by redirecting resources away from growth towards stabilization, as is the norm in any IMF program. But the real scale of the adjustment has become more pronounced since April 2021. The delayed acknowledgement of the reality – that Pakistan was not ready for a growth spurt at that point in time, especially not with fiscal and monetary stimulus – now brings enormous cost in the shape of hardship for the people as well as for industry. Staying on track with this program going into an election year will be extremely challenging for the government. Let’s see if they can muster up the will to walk the path they have embarked upon. n