12 minute read

After three years in the wilderness can Summit Bank be resurrected?

After being frozen in time for three years, the bank is making quick moves to get back in the race

For the past three years, it has almost been as if Summit Bank was pretending it did not exist. In that time multiple finance ministers came and went, the coronavirus pandemic began, peaked, ebbed after vaccines were rolled out, and peaked a few more times for good measure. But in all that time Summit Bank remained stuck in time. In 2018, following a highly publicised and politically entangled money laundering scandal, the bank failed to release its financials prompting raised eyebrows. In 2019, the bank once again failed to release its financials and as a result of this non-compliance shifted to the defaulters segment of the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). Following the demotion at the stock exchange, the bank made a feeble attempt to correct course by releasing their 2018 financials in 2020, but for a third consecutive year failed to call an Annual General Meeting (AGM). And a full-blown money laundering investigation initiated by the FIA and NAB following a scandal involving political bigwigs such as Asif Ali Zardari and his sister Faryal Talpur was not the extent of their troubles. The bank was also facing constantly rising pressure from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) over its inability to fulfil regulatory requirements due to a deteriorating financial condition. In response, it very much appeared that Summit Bank had wilfully buried their head in the sand and were trying to ride the tide of the scandal out.

Advertisement

That is, until now. Over the past three months the bank has publicly released their financial statements for 2019, 2020, and 2021 (up until 2021). Following all of these mandatory disclosures, the PSX has also moved them up from the defaulters segment to its “normal counter” - meaning the bank’s stocks are up for trading once again. That will not be the end of it, as Summit Bank looks to recover and get back into the race after three years in the wilderness.

Profit spoke to Summit Bank CFO Salman Zafar Siddiqui, and the bank’s Head of Marketing, Corporate Communications & Service Quality Naiyar Saifi to get an understanding of what happened at Summit, how it got to the point that it did, and what measures it is now taking to climb out of the financial, legal and regulatory quicksand it has been stuck in for so long.

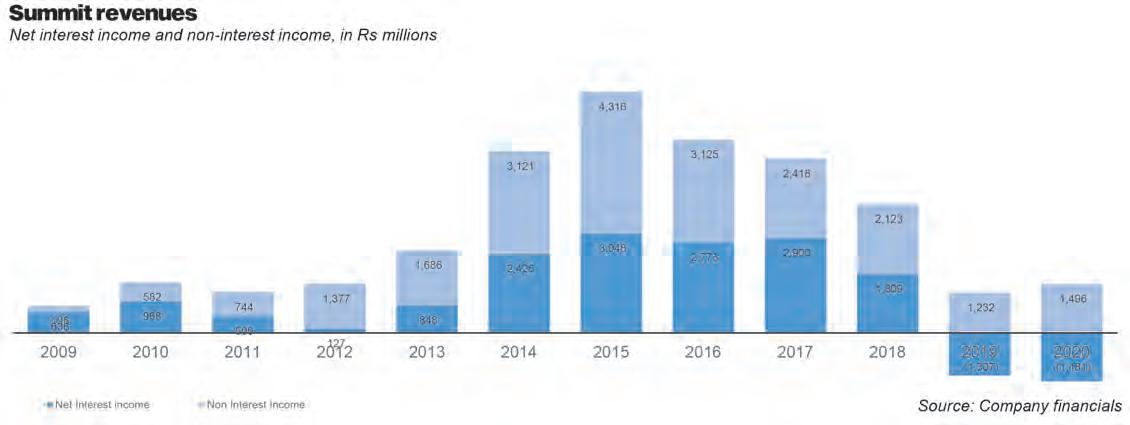

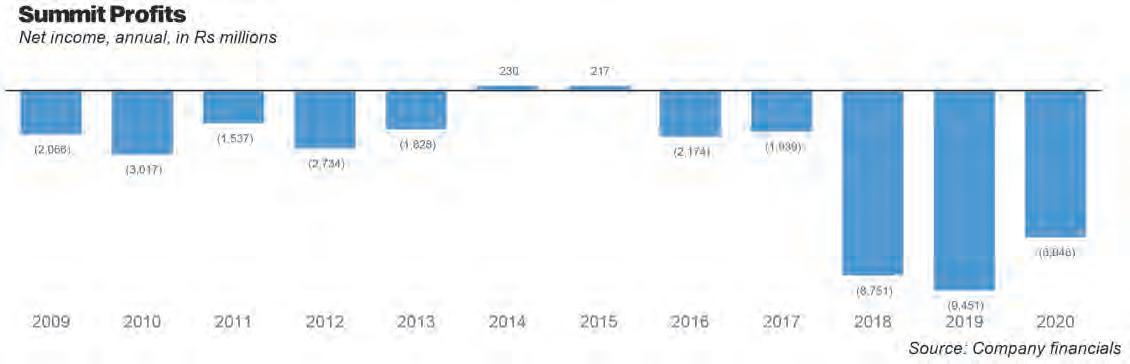

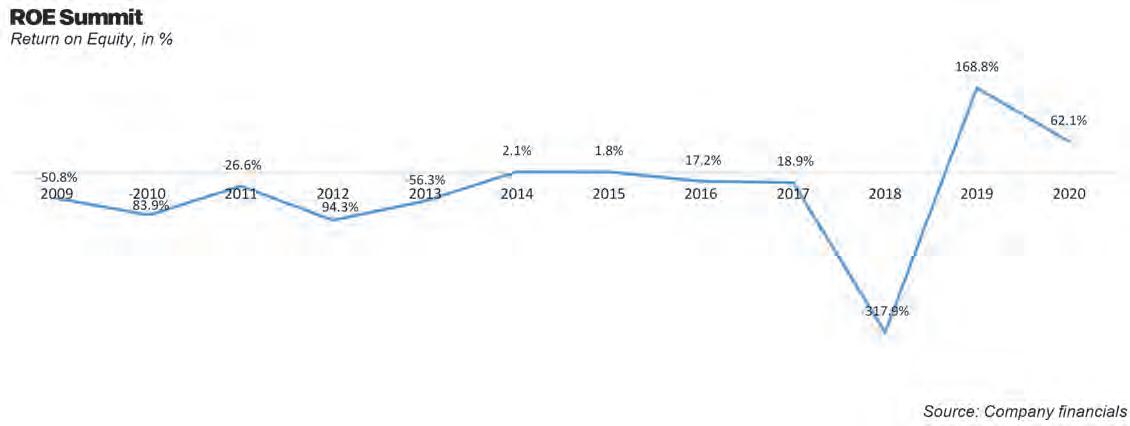

Bad results

Summit is not a very profitable bank. In fact, it has posted a net profit after taxation only twice, in 2014 and 2015, in the past 10 years, that too a small one, Rs217 and Rs230 million respectively. On the other hand, its losses in the other eight years under consideration have been in the billions; a net loss of Rs 9.45 billion in 2019 is no small number. While the bank’s losses must be a source of legitimate concern for its shareholders, it is Summit’s net asset and capital adequacy position that was the source of its run-in with the central bank. “We had some problems with the regulator which is why financial statements were withheld. CAR was a major concern,” Siddiqui tells Profit. The year 2018 was the beginning of three very tough years for Summit. SBP started having legitimate concerns about the bank’s solvency and depositors’ security. Deposits fell by 42%, net assets dropped by 73% and Capital Adequacy Ratio went negative to -8.02%. The following year, the bank had negative equity of Rs 5.59 billion which meant it was no longer solvent while CAR fell further to -25.03%. As per its latest financials, up until September 2021, negative equity has ballooned to Rs 13 billion while CAR is a whopping -53.66%. This wasn’t the least of Summit’s financial woes; non-performing loans skyrocketed as the number more than doubled, from Rs 17 billion in 2017 to Rs 36 billion in 2018. The bank’s NPL ratio stood at 64.54% while the industry ratio was 8%.

Fake accounts case

The fake accounts case involves alleged money laundering worth billions of rupees through 32 bank accounts, which were opened in five banks. Of those accounts, 15 were opened in Summit Bank. The FIA’s investigation report revealed a pattern of flouting the law against money laundering on the part of Summit Bank employees, who appeared to be operating under direct orders from the founding CEO Husain Lawai. Lawai and Zardari are old friends, and Lawai spent a considerable portion of the 1990s and 2000s in exile, fighting charges of money laundering on behalf of Zardari. He was exonerated of those charges in the UAE in 2002 and the charges against him in Pakistan were dropped in 2008. The FIA alleged not only that Summit Bank failed to catch the money laundering going on through its accounts, but actively facilitated it through a procedure put in place by the bank’s CEO himself and one in which a large part of the bank’s staff was also involved. The FIA also alleged that bank’s majority shareholder, Abdulla Hussain Lootah, a member of one of the oldest and wealthiest families in Dubai, may have been a beneficiary of the money laundering himself. As if this was not enough, the National Accountability Bureau went ahead and arrested Husain Lawai. For his part, Lawai maintained his innocence throughout.

“We took a big hit that year. It was a very difficult time for the bank. Our assets were depleted and there were a lot of defaults,” says the CFO.

Short on capital, the bank was forced to liquidate much of its government securities/ fixed income portfolio that includes Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIB), T-Bills and Ijarah Sukuks, to build its assets back up. Its collective carrying value of government securities in 2017 was Rs 89.8bn which came down to Rs 16.3 billion the following year, an 81.8% drop. The bank could not sell any more due to SBP’s Statutory Liquidity Requirements (SLR) that requires banks to maintain a minimum level of eligible securities on its books.

These numbers only became available in 2020 when the 2018 financials were published, representative of a bank on the brink of collapse. More importantly, the numbers showed a bank shrouded in secrecy and wanting to keep things secret. The question was, why would they do that when the results were not different from what anyone expected?

Fresh capital injection

Summit’s change of category at the PSX had no effect on the financial condition of the bank, in fact, according to Siddiqui, the bank was not even aware that PSX had moved it to the normal counter. It therefore, on the face of it, should make no difference to how the SBP looks at Summit either; it is still a sick bank that isn’t solvent. According to Siddiqui, the intent shown by Summit’s majority shareholder Abdullah Hussein Lootah to secure a controlling interest in the bank through a fresh equity injection amounting to Rs 15 billion, has satisfied the SBP. “SBP has formally approved the Lootah transaction. We have done everything from our end and are just waiting for a tender offer from the investor. After that, it is just a procedural matter which shouldn’t take more than 60 days”, Siddiqui added. Lootah had sent an offer letter in October of 2021. In the letter he had asked for 51% voting shares, and new ordinary shares through fresh equity injection. The board agreed to handing over 5,976,000,000 ordinary shares without right to Lootah, and also increased the authorised capital from Rs28 billion to Rs90 billion. At the time of filing this story, that tender offer necessary to take the transaction forward had not come in. According to Summit’s head of marketing Mr Naiyar Saifi it is “expected any day”.

If the name Lootah sounds familiar, that is because he was named as one of the main suspects by the FIA in the money laundering case against Summit. NAB was pursuing the case as well and it was only after he became approver against Asif Ali Zardari - the main accused in the case along with his sister Faryal Talpour - that his arrest warrants were cancelled.

Lootah putting money back into Summit to ‘revamp’ it after serious financial troubles brought on in some part due to the money laundering scandal is quite ironical, because the FIA, during the course of its investigation revealed that a sum of Rs2.49 billion had actually been paid out to Lootah by the bank, details of which

are at best murky.

Subjective regulation

One thing that becomes clear is that one way or the other Summit Bank continues to linger on. This begs the question of where the SBP draws the line when it comes to similar operations that on paper do not seem viable anymore and are at risk of failing? For any commercial bank operating in Pakistan, perhaps its biggest asset is the commercial banking licence that it holds. This is simply because it acts as the primary barrier to entry for new players in the industry as the State Bank of Pakistan no longer hands new ones out and doesn’t allow just anyone to secure an existing one by buying a bank. It is therefore a privilege that not only has to be earned but maintained by working within the stipulated regulatory framework as laid down by the central bank. That these regulations are fluid in nature forces banks to update their systems and adapt. However, this regulation can sometimes be quite subjective. What happened at KASB can perhaps lend some context here.

KASB was sold for Rs 1000 as a token price to Bank Islami that also took over its liability of Rs53 billion in deposits. The former ownership and management of KASB maintains that this transaction was conceived and forcefully executed by the SBP in an unjustified manner without giving them a fair chance at restructuring the bank, shooting down proposals the bank had repeatedly shared with the central bank.

That forced sale became the subject of some controversy. In April 2018 the Public Accounts Committee of the National Assembly asked the Supreme Court to take suo moto notice of the merger and termed it a “scandal”. Then in December 2020 the National Accountability Bureau opened an investigation into the decision, with talk of arrest warrants being issued for Ishaq Dar and Ashraf Mahmood Wathra, then SBP Governor along with a number of other State Bank officials.

The State Bank shot back at this move, saying the move will demotivate SBP employees and defended its decision saying “the bank and its sponsors were found engaged in fraudulent practices and siphoning off more than Rs3bn from the bank” and argued that KASB was “the only bank which had a negative CAR.”

“All the actions taken were permissible under the law and were duly approved by the Ministry of Finance and SBP’s Board of Directors” its statement concluded. It was at least partially due to this investigation that present Governor of the SBP has pushed for putting the State Bank beyond the reach of NAB under the SBP autonomy bill making its way through the Senate.

KASB management alleges that it was targetted by the SBP for unfair reasons, and go on to allege malfeasance as one of the motives, especially on the part of former Governor Wathra and finance minister Dar.

In comparison, Summit has been more or less in the same regulatory soup as KASB for some years but has been treated very differently. It was allowed to not print its financials for three years while its restructuring and recapitalisation plans were accepted.

It would seem therefore that a business plan in tandem with an offer of investment

should be enough to satisfy the SBP. Apparently not. A senior former central banker explained that there are a lot of considerations in such situations other than just the bank’s balance sheet and capacity to recapitalise. “When push comes to shove, political connections, ones that Summit is known to have plenty of, go a long way”, they added.

“The money Lootah has promised is yet to come in and his tender offer remains pending so it’s all up in the air at this point. What is surprising is the leeway SBP is giving to Summit merely on the basis of a transaction involving a controversial investor that may or may not be executed”, commented a senior banker on condition of anonymity.

The Islamic shift, new management and rebranding

Even if the fresh equity is injected into the bank, it does little to address the CAR and solvency problem. This much was admitted by Siddiqui. “However, the investment is just one part of a larger strategic plan to completely overhaul the bank”, Siddiqui added. Summit plans to convert into a fully Islamic bank over the next few years. But this is easier said than done.

“One of the conditions for the investment by Mr Lootah is the commitment towards transforming Summit into a purely Islamic banking concern. This will of course take time because the asset conversion process is very complex and will take some time to complete”, commented Siddiqui on the new direction the bank is taking.

“In addition to being lower cost, this strategy also aligns with SBP’s goal of having more Islamic banks in the country”, he added. Summit has more or less done away with its previous management, starting with the CEO who has extensive Islamic banking experience in Pakistan, downwards to group heads of revenue-generating arms of the bank.

This was a necessary step towards building a team distinguishable from the one whose poor decision making led the bank to where it is today. Additionally, according to Saifi, there are plans to create a completely new corporate identity and do away with the Summit bank name. “We are going to completely rebrand as the Summit name is tainted, basically a stalemate. No foreign banks want to work with us”, he added.

Yet, it is important to understand why Summit is not an easy bank to turn around. An amalgamation of three smaller banks, namely Arif Habib Bank (2009), Atlas Bank (2010), and Mybank (2011), Summit had an uphill task of ever becoming profitable despite its founding CEO Hussain Lawai’s best efforts.

None of the three banks combined to create Summit were ever viable entities. Apart from a nearly non-existent retail banking portfolio, a solid consumer banking base was also lacking. Although Lawai tried his best to address these issues (Profit has covered this extensively in a previous story on Summit), it was never enough. Summit therefore carries a lot of financial baggage and cosmetic changes alone such as ‘going all Islamic, 'complete management changes’ and ‘rebranding’ may not be enough to shed it. n