23 minute read

Newsmakers 2021 35

Profit takes a look back at the most significant names that were in the headlines for the year past, what note they ended their year on, and what the year ahead might have in store for them

By Abdullah Niazi

Advertisement

Shaukat Tarin

In the space of less than an entire year, Shaukat Tarin has managed to become finance minister, be de-jure demoted to Adviser to the Prime Minister on Finance, win a senate election so he is able to present the upcoming budget to parliament and once again appointed as federal finance minister. Just one of those things would be an event of a lifetime for most people. With the amount of effort the PTI is putting in to keep Tarin in the economic driving seat, it is hard to imagine that there was a two-week period in April where the government was strongly denying rumours that Tarin was slated to come in and up-end Hammad Azhar’s then nascent run at the wheel of the ship. However, eight months down the line Tarin has proven to be a level-headed and consistent guide at the very least. He came in without any big punches, and stayed on course in terms of not interfering in the value of the rupee - much as he did between 2008-10 when he was finance minister in the Gilani cabinet. With a disagreement over why the country is facing inflation still brewing between the Tarin-led finance ministry and the Reza Baqir led State Bank, it is very likely that he will be a mainstay in the headlines in the year to come.

Reza Baqir

State Bank Governor Reza Baqir has made an impression. The job of SBP Governor is often a bit overstated in terms of workload if not importance. At the end of the day, any governor of the state bank has a few levers on their desk that can be pulled to change policy rates and adjust monetary policy. Because of this, most SBP Governors often go through their tenures quietly doing their jobs without much fuss. Reza Baqir has been different in that sense. He was for quite some time known among finance circles as “Agent 007” - both because he maintained the interest rates at 7% time and again, and as sly allusion to ridiculous claims that he is some sort of ‘agent’ because he worked for the IMF before getting the top job at the central bank. Governor Baqir spent 2020 being begrudgingly admired even by his detractors or the bank’s decisions to slash interest rates and boost jobs as much as possible in a crisis. This year has proven to be the one in which he has come into his own, and made tough calls when he has had to. We can only watch with anticipation what the Governor

will do next year.

Zia Chishti

The Pakistani origins American CEO of The Resource Group (TRG) and up and coming tech company Afiniti saw a disgraceful downfall after the testimony of a former employee at Afiniti saw him implicated in sexual assault allegations. The harrowing allegations also saw an effect on TRG stock in Pakistan, but it took a while for Chishti to be officially removed as CEO of TRG Pakistan. While his absence has already sent shockwaves through Afiniti, TRG Pakistan stock has managed to stabilise and it is yet to be seen how far reaching the effects of his downfall will be.

Pakistan Cricket Board

The Pakistan Cricket Board closed 2020 on a high. After years of being in stagnant loss, the board declared an after tax profit of Rs 3.8 billion, with reserves of Rs.17.08 billion compared to PKR 13.28 billion in the 2018-19 financial year. Other than the net profit, the board has also seen an increase in income of 108pc, bringing in Rs 10.696 billion through different sources this year compared to the year before. Fast forward to the middle of 2021 and everything was in shambles. New Zealand and England pulled out of tours they had promised causing millions of rupees in losses to the board, star CEO Wasim Khan resigned, and the board was suddenly being headed by Ramiz Raja, a former cricketer with no experience in finance. Things seemed bad. But almost as if they were galvanised by the team stepping up and having a stellar performance in the 2021 T20

World Cup, the board has in the last few months of the year had some big wins. New Zealand has promised to tour Pakistan twice in 2022 to make up for the losses incurred when they cancelled their tour to Pakistan, and both England and Australia have also promised to tour the country. The appointment of Faisal Hasnain as new CEO has also been followed by the board signing lucrative broadcasting deals with PTV Sports and A-Sports which should bode well for the future.

Azfar Ahsan

Azfar Ahsan was featured on Profit’s cover this year back in

October in an in-depth story on corporate lobbying in Pakistan. And that was even before his lobbying firm hired former Chief of Air Staff Air Chief

Marshal Sohail Aman or before he was appointed Chairman of the Board of

Investment (BoI) with the status of a minister of state. Before this year,

Azfar had largely been unknown and out of the public eye. He was more of a backstage character, especially as the organiser of conferences and founder of the ‘Corporate Group Pakistan.’ With his behind-the-scenes role converted to a more public one, the coming year will be an interesting one for Azfar.

Hammad Azhar

Hammad Azhar’s 2021 saw him get the unfortunate distinction of being the shortest lived finance minister the country has ever seen. When he was brought into the office, it seemed it was an attempt by the PTI to return to its core values and present a new poster-boy to the nation. But after less than three-weeks in office, he was shifted to the energy ministry, where he has presided over a badly managed gas crisis, a strike at petrol pumps, and a host of unfortunate television appearances on the Shahzeb Khanzada show. To his credit, he has tried to be open and available to the public, and has followed in the well-liked footsteps of his father Mian Azhar, who was a very popular governor of Punjab in his day. At barely 40 years old, Hammad Azhar has a long political career ahead of him. While this year may have been one of hits and misses, he will be one to watch out for in the future.

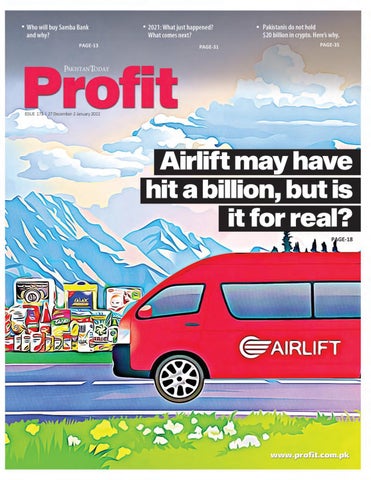

Airlift

Airlift has reportedly successfully raised another investment, another eye popping figure this time but an unusually large one - $350 million.

The raise is undoubtedly massive, and together with the previous $85 million announcement this year, will take

Airlift’s funding alone to more than half of what has been raised in total by Pakistan’s startups this year. What is also big news is that they seem to have managed to get a valuation of $1 billion. There will be a lot of speculation surrounding this, but could this be Pakistan’s first even unicorn? Or will this dizzying high be followed by a resounding crash to a dismal low? The year ahead will be on to watch out for.

KIA Lucky Motors

Between August 2019 to August 2021, KIA Lucky Motors managed to sell 25,000 models of its crossover SUV, the KIA Sportage. That translates to roughly more than 1000 cars per month. And to roughly translate those numbers into words - that’s a pretty big deal. KIA entered Pakistan’s automobile industry as an underdog, especially given the very strong triopoly that exists between Japanese automobile companies Toyota, Honda, and Suzuki. The South Korean KIA has managed to circumvent the norms of the auto industry in

Pakistan, and set the trend for the introduction of cheap crossover SUVs - a category of cars previously unavailable in Pakistan. Their success has also emboldened other entrants on the market like the MG and Hyundai. KIA has almost single handedly managed to bring life to Pakistan’s car market and have made the ‘Big Three’ sweat. That in itself is a huge achievement. While they have faced issues in the second half of the year with their smaller unit the ‘Picanto’ being short in supply because of the global semiconductor chip shortage, it seems KIA will go on to have a strong 2022 as well.

What just happened? What comes next?

A year that started off very strong is ending on a starkly different note. Where will the next year take us?

By Khurram Husain

Rarely have we seen such a sharp and rapid reversal in a government’s fortunes as we saw in 2021. The year opened with growth powering ahead, the fiscal and current account deficits narrowed, the government basking in the applause of the business community. The economy had turned the corner, we were told. Growth had returned, foreign exchange reserves were high, the twin deficits had been conquered and the curse of repeated boom bust cycles finally broken. The State Bank Governor took to the air around March to declare that this particular bout of growth was different from all preceding ones because it was sustainable whereas the earlier ones were not. Inflation was still high, but it was due to one off factors, we were told, which would be sorted once the temporary disruptions, such as a poor wheat harvest the previous year, were taken care off by the end of the wheat harvesting season in June. But by year’s end it had all vanished. The current account deficit is now powering ahead faster than anything else, and if present trends continue till the end of the fiscal year, it could come in as high as $17 billion, too close to comfort to the $18 billion “record high deficit” that this government never ceased to remind us all it inherited from its predecessors. The State Bank projects this figure to be closer to $13 billion by June, largely in the expectation that import pressure will subside in the coming months due to falling commodity prices and lower demand at home. Even at $13 billion, it will be a challenge to manage. Inflation has spiked to touch 11.5 percent with no signs of abating any time soon. The exchange rate has depreciated by more than 18 percent since the start of the year and remains under pressure. Interest rates have spiked by 275 basis points in three months as the “forward guidance” issued by the State Bank at the start of the year promising all further rates will be “gradual and measured” was abandoned dramatically due to “unforeseen circumstances”.

Meanwhile the applause from the business community at the start of the year gave way to an acrimonious exchange of serious allegations between government ministers and industry leaders by the year, driven on by gas shortages and rising interest rates. The country’s apex chamber, the FPCCI, called the gas crisis a “conspiracy” against the government, and implied that its own ministers were involved in it.

The one thing that remained constant from the beginning of the year till the end was the government’s desire to resume the IMF program, which was suspended in April 2020 following the imposition of the lockdowns. Two key demands – to pass an amendment to the State Bank Act giving the central bank sweeping autonomy to make decisions free from governmental interference, and a finance bill to withdraw a vast array of tax exemptions along with sharp curbs on development spending – are proving to be serious sticking points. The year began with the government promising to get back onto an IMF program within weeks. It ended with this promise being repeated with no end in sight.

Along the way we saw two trajectories diverge. One was the government’s triumphant rhetoric about restoring growth. “We have moved from stabilisation to growth” declared Shaukat Tarin in June during his budget speech. “After considerable effort, the government has finally succeeded in stabilising the economy and putting it on the path of growth.” A few months earlier the government was celebrating an unusually high GDP growth rate figure of 4 percent that took most analysts by surprise. They revelled in the attendant growth in revenues, 18 percent, which they argued was “the highest in five years”, the growth in exports, 14 percent, which they said was “remarkable” and owed itself to government support. “A variety of concessions were offered to revive the export industry” Tarin declared in his budget speech, “which included rebates, duty drawbacks and subsidies on utilities”.

But below the surface and triumphalism, trouble was brewing. Key indicators of economic health were cratering while key metrics of growth were hitting a plateau. Food inflation nearly doubled between January and April before coming off its peak, giving the State Bank the opportunity to declare that this trend was “largely supply driven and transient”. The index of Large Scale Manufacturing, one of the key metrics they used to argue for their industrial revival, had already peaked in January, and by the summer had fallen back to the same levels it was at a year earlier at the start of the whole growth story.

More worryingly, the dreaded current account deficit made its return at the same time as this triumphalism was rising towards its peak. From January to March it crossed $600 million while the government swatted away concerns about it by saying it is driven by one off events like unusually large wheat imports due to a bad harvest. From April to June it crossed $2.5 billion. By year end it was still contained at below $2 billion (for the full year) giving the government room in which to

argue that it remains “manageable”.

None of these trends subsided. Inflation proved to not be transient and by year end the State Bank was forced to raise its fiscal year inflation target to 11 percent from 9 percent. The current account deficit powered on, crossing $3.4 billion by September and $7 billion by November. The large scale manufacturing index flattened out around 140, oscillating slightly around this level from July to October, below its level from the same period in the previous year. The rupee approached 180 to a dollar in the interbank market and scarcities began to be reported in the open market in many cities around the country, forcing the State Bank to announce more and more measures to restrict its sale.

All this was coming. Anybody who read the agreement that Hafeez Shaikh had signed with the IMF back in April knew the growth boom they were touting was built on a massive stimulus and that stimulus had to be unwound. It could not continue. Shaikh had effectively agreed to roll back all the industry support that Tarin listed as his government’s successes, grant autonomy to the State Bank so it could never again become a source of lending to the government or runaway printing of money through refinance schemes. A raft of new taxes had to be imposed, expenditure cuts implemented and interest rates hiked.

Days later Shaikh was unceremoniously dismissed and replaced with Tarin who backpedalled on all these commitments and promised he would renegotiate the conditions with the IMF. In June Tarin announced an expansionary budget with higher expenditures targets and an ambitious tax target that banked heavily on the potential revenue windfall from expanding the use of tax registered point of sale machines in retail outlets. All summer he argued that he would produce the revenues the IMF wanted to see without burdening industry and consumers with heavy taxes on essential items or fuels. In short, he agreed to power ahead with the stimulus through high government spending and low interest rates, thinking that somehow he would be able to manage the resultant fallout.

The State Bank played along. In March the Governor gave televised interviews touting the revival of growth, pointing to the rising foreign exchange reserves, and argued that “this time the growth is sustainable, unlike previous episodes”. But instability was already knocking at the door. In May the exchange rate was hit by a strong bout of volatility and began a slide that took the rupee from 150 to a dollar to 175 by October, with no end in sight. Foreign exchange reserves were being built through heavy recourse to borrowing, with two bond flotations in March and July that raised $3.5 billion between them.

By September the consequences of powering on became too large to manage. Reports emerged of massive State Bank interventions in the foreign exchange markets to try and dampen the volatility that had battered the exchange rate all summer. The current account deficit continued rising, and despite a fresh injection of $2.8 billion by the IMF as part of a global initiative to support foreign exchange reserves around the world to mitigate the effects of the Covid lockdowns, Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves (held by the State Bank) fell from a peak of $20.1 billion in August to $18.1 billion by the middle of December. Had an additional $3 billion in borrowed support from Saudi Arabia not arrived in late November, this figure would have been closer to $15.1 billion. The level of the reserves by now had fallen to below 2.8 months of import cover, far below their level in August of 3.3 months.

In September the realisation began to sink in among top levels of government decision making that serious course correction is needed. Tarin spoke for the first time of “overheating” in the economy, a situation where growth is accompanied by rising inflation and destabilising deficits, particularly the current account deficit, which puts pressure on the exchange rate. The State Bank shifted gears and raised interest rates for the first time since the massive rate cuts from the summer of 2020, announcing that it would now be “gradually tapering the significant monetary stimulus provided over the last 18 months.”

But the acknowledgement was still muffled and muted. In the accompanying statement released with the rate hike decision, the State Bank could still say that real interest rates will “remain accommodative in the near term” barring “unforeseen circumstances.” But circumstances did not cooperate with their wishes. The October and November current account deficits remained high, taking the five month figure to $7.1 billion and putting the economy on course to hitting a level it had last hit in 2018.

And then came the jolts. In two surprise moves the State Bank sharply hiked the discount rate by 2.5 percent citing “unforeseen circumstances” and announced a new calendar that would see more frequent monetary policy decisions. The financial markets smelled blood and started demanding sharply higher yields in government debt auctions and the flight to the dollar picked up pace. The finance minister lashed out at the banks, accusing them of engaging in speculative trades in foreign exchange, and threatened them with punitive action in a televised interview. The State Bank Governor dialled down some of these remarks in a subsequent interview given to Profit magazine, saying he would not call the banks’ behaviour speculation, preferring the term “self fulfilling expectations of buyers and sellers” instead.

Tapering the stimulus was going to be tricky business, it seemed. And to top it off a fresh bout of winter gas shortages hit the economy, borne in large measure from mishandled LNG purchases made earlier in the year, when winter supplies have to be arranged. Reports emerged of surplus furnace oil stocks imported against faulty demand projections made by the power division, while refinery stocks filled up to the brim with furnace oil that the power sector was not lifting, forcing cuts in throughput or outright shutdowns. Everything was starting to fall apart. The business community, particularly the textile exporters who had been the darlings of government largesse during the growth boom, took to the airwaves to accuse the government of severe mismanagement while government ministers shot back accusing them of being rent seekers addicted to subsidies. The entire narrative of triumphalism around the growth figures was now inverted, with the love affair between government and big business turning looking more and more like a messy divorce.

The year 2021 began with industry booming, exports rising and the government touting its growth miracle. It ended with industry closures, rising debt, inflation, deficits and pressures on the exchange rate. It began with the government saying it had revived the economy. It ended with the same government acknowledging that the economy could not afford to grow in the way that it was.

If 2021 felt a bit like the high an addict gets from a fresh injection, 2022 will be the hangover. A government fractured from within, with its relationships with key power brokers in the country frayed severely, and battered at the ballot box will have to undertake a tough adjustment to reality. It will have to impose hefty taxes on an inflation-burdened citizenry, further raise interest rates on a business community already at loggerheads and find a way to work with the opposition to get critical legislation passed through parliament. Their hopes are pinned, for the moment, on the projection that global commodity prices would have peaked by March. But if “unforeseen circumstances” should once again intervene to dash those hopes, they could find themselves chasing the financial markets in an effort to find the right yields at which government debt becomes palatable for its creditors. Already their forays into global markets for a fresh Sukkuk floatation have not attracted as much interest as their earlier forays did in 2021. Without fresh financing coming in from abroad and bereft of political capital at home, the government is likely to be left clutching at straws for a lifeline as it heads into an election year. n

The year that was: The highs and lows of the stock market

Continued waves of Covid-19 marred what was supposed to be a strong recovery year

By Ariba Shahid

While the stock market might not be (debatable, I think it isn’t) an accurate indicator of the economy, it is an important metric to look at when talking about the financial world and its performance. Off to a good start, the PSX opened on January 1, 2021 at 44,434.80 points and gained due to the reopening of global economies and a slowdown in COVID infection ratios for the country.

However, with recurring Covid-19 waves, pressure on the external account, rising inflation, and downgrading in the MSCI list, the market witnessed a downward turn. With another round of monetary tightening underway, the PSX witnessed some withdrawals into fixed return assets amidst this higher interest rate environment.

The index, however, closed on 43,901 points generating a 0.3% return. As per Arif Habib Limited’s Pakistan Investment Strategy 2022, this is equivalent to a -9.99% return in USD basis. As per the report, the Research team anticipates the index to close at 55,036 points by December 2022. “Our December 2022 target for the KSE 100 Index is set at 55,036 points, portraying an upside of 25.4% from index closing of 17 Dec 2021.”

This year, tech was a sector gainer up 904 points, followed by commercial banks with a positive 870 points. Systems limited was a winner this year with a positive contribution of 810 points making 90% of the contribution in the Tech sector. Cement, Oil & Gas Marketing Companies, and Refineries didn’t perform that well on the PSX, negatively contributing with 505 points, 362 points, and 353 points respectively.

Volume leaders

In terms of volumes, worldcall led the market by more than double of Byco, the second most traded share in terms of volumes. Approximately 55 million shares of worldcall were traded, whereas 25 million for Byco, 19 million for HUMNL and Telecard.

Just a reminder for all those that have forgotten, On the 26th of May, the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) saw an all-time high daily trading volume. As usual, government ministers were quick to jump on the news to try and portray the big day at the stock exchange as an indicator for the economy. Federal Minister for Planning and Development, Asad Umar, attributed the development to the market reacting to signs of sustained economic recovery. Other government ministers and spokespersons joined in on the fanfare.

The traded volume clocked in at 1,560 million shares in today’s session, which is the highest ever in the history of the PSX, exceeding the previous record by a massive 39%. Carrying the lion’s share of gains for the investors was Worldcall Telecom Limited (WTL), which added volumes of 707 million shares to the overall trading activity — almost half of the total intraday volume, while achieving a steep gain of 41.23pc in its share price. This was all backed on an acquisition attempt which ultimately ended up turning into an alleged pump and dump. This is just an example of how volumes and indices can be misleading.

Summary of Capital Raised

Throughout the year, 8 equity IPO transactions were witnessed. The very fact that the PSX managed to raise capital during a pandemic is something to celebrate especially considering the depth in the market and the investor base.

An IPO is the first time a company is able to sell securities to the public. IPOs are called Primary Markets. Their purpose is to bridge companies that need funds with investors. Now, there are different things that you can sell through an IPO. What we have been talking about up until now is selling equity in the company in the form of shares. However, you can also sell quasi equity as well as debt using an IPO.

If we dive deep, out of the 8 transactions, 6 new listings were on the main board while the remaining 2 were on the newly introduced GEM board. The six listings are Panther Tyres, Service Global Footwear, Citi Pharma Limited, Pakistan Aluminum Beverage Cans Limited, Airlink, and Octopus Digital Limited. The two Gem board listings include Universal Network Systems Limited and Pak Ago Packaging Limited. Combined, all six managed to raise equity worth Rs 19.92 billion during the calander year.

The GEM Board is reserved for “growth companies” carrying higher investment and liquidity risks than mature companies listed on the main board of the exchange.

Moreover, 16 companies issued right shares during the year which resulted in Rs 12.1 billion in capital being raised. Businesses weren’t too keen on raising capital considering cheaper credit and finance that was available in the form of TERF by the SBP.

Potential in the market?

While we’ve talked about this in detail on how oversubscription is a result of too much regulation, it is also a proxy that one can use to determine how excited the market is about a company that they believe in. Let’s take the case of Octopus. the IPO was oversubscribed 27 times by the end of the two day process. The company received offers of over 745.6 million shares against its offer of 27.35 million at the initial price of Rs 29 per share. To put this in perspective, the IPO was fully subscribed within the first half hour on the first day. This shows how hungry the market is for successful tech companies.

That being said, 2022 might not be a massive year for capital raising considering the estimated equity that will be raised is Rs 14-15 billion as per AHL Research. They expect this to be raised through 8-10 new IPOs in the automobile assemblers, pharma, chemicals, textiles, and construction and materials sectors.