5 minute read

Helen LaFrance MemoryPainter

★ by SUSIE FENWICK

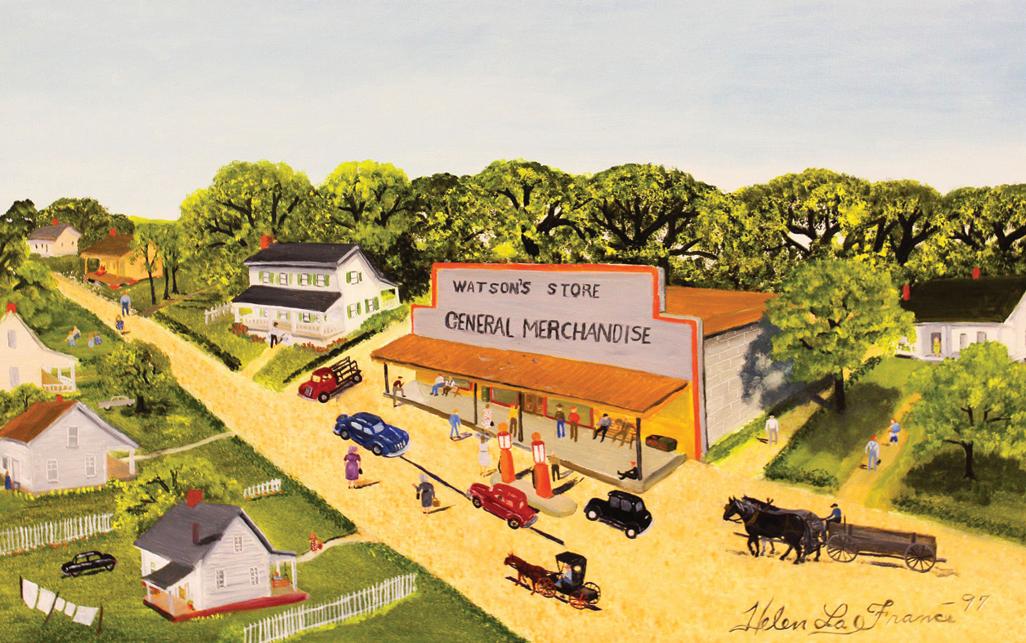

A CELEBRATED CENTENARIAN LEAVES A LEGACY OF SOUTHERN ART CRAFTED FROM BERRIES AND TWIGS

A CENTURY AGO IN RURAL GRAVES COUNTY, A LAND SHE STILL CLAIMS AS HOME, Helen LaFrance was born to James Franklin Orr and his wife, Lillie May. She was named Helen by her father to offset what he considered the highfalutin name, LaFrance, chosen by his wife to commemorate the liberation of France at the end of WWI. Just one generation removed from slavery, the baby girl had skin colored the deep, rich shade of dark, fertile, bottom soil. Her hair coiled like a twist of Kentucky tobacco pulled from an old timer’s bib overall pocket. The little child had soft brown eyes just waiting to blink scenes into memory and tuck them in her psyche for safekeeping. Someday her little fingers would grow into dexterous digits channeling precious scenes overflowing from mind to canvas through paintbrushes. Helen LaFrance would make a name for herself artfully documenting scenes of a rural Kentucky countryside lost in the name of progress and a way of life remembered by few.

I met her in a nursing home in Mayfield where she has been living for a number of years. A shadow of the woman she once was, resting in bed, and staring at the wall; Helen LaFrance was a little fidgety. She didn’t know what to do with now idle hands that had occupied the better part of her life by farming, working in hospitals, tobacco warehouses, ceramic factories painting whiskey bottles, and marrying five times to three different men, as well as minding the children of others.

Recognizing me only as a stranger in her room, she homed in with an artist’s eye to a feature catching her fancy; my teeth. She liked them.

Asked how she remembered scenes vividly enough to make them come alive on canvas years later, Ms. LaFrance said, “I canned my memories like other folks canned beans and peas.”

Always a noticer, the beloved southern painter recollected scenes from girlhood; looking around and committing to memory all she hoped to preserve through painting. Helen seemed to have a premonition that someday, in the cold dark days of old age, she would savor those memories like others would relish the taste of a harvest’s bounty in the long barren stretches of winter.

With no formal training and existing outside the cultural mainstream, she was considered an outsider in the art world but was acknowledged as a memory painter. The folk artist followed her mother’s advice, “paint what you know.” Showing an interest in art at an early age, LaFrance’s mother schooled Helen in painting by guiding her tiny hands as she sketched familiar scenes on the back of old wallpaper or any other scrap of paper. Her art supplies consisted of paint her mother made from laundry blueing and berry juices and twigs for paintbrushes.

It wasn’t until she was in her 40’s that life afforded her the quiet time and resources needed to focus on painting seriously. She took up residence in an old abandoned school bus for her studio. The peak of her artistic career was in her late 80’s. Not limited to two-dimensional media, LaFrance was an exceptional quilt maker, wood carver, and doll maker who dressed her articulated creations in handmade textiles.

Besides painting folk art, the self-taught artist painted a series of biblical interpretations, which were described by Dave Perkins, Associate Director of Religion in the Arts and Contemporary Culture at Vanderbilt Divinity School.

“These works have a life force, the effect of which is that they are not mere renderings of biblical events or memories of personal visions or revelations, but something alive. The works are the visions. The paintings are a mode of doing theology,” he wrote.

Still her memory paintings conjure the strongest feelings of a shared common experience.

Her art is included in over 100 private collections, and she has shared her western Kentucky countryside through art with celebrities Oprah Winfrey, Gayle King, Bryant Gumbel, and contemporary artist Red Grooms who all include her paintings in their collections. Hundreds of her paintings have been sold around the world spreading her memories of a bygone rural Kentucky globally. Her art has been exhibited widely across Kentucky and the rest of the United States and also in European Galleries. Exhibited in the Van Nelle Collection of tobacco art in Amsterdam and purchased on a visit to the tobacco barn where Helen LaFrance worked is her depiction of workers rolling cut tobacco.

Helen LaFrance is lovingly documented in the musical play by Marilyn Jaye Lewis, “Tell My Bones: The Helen LaFrance Story,” and also in a Kentucky Educational Television documentary. Accolades include the prestigious Folk Heritage Award for 2011, the Kentucky Arts Council’s Governor’s Award in Arts, and inclusion by the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights in the Gallery of Great Black Kentuckians for her art despite growing up under oppressive Jim Crow laws with basically no formal education.

Helen LaFrance's 100th birthday was celebrated in November 2019 and was covered by the New York Times, Washington Post, Miami Herald, and the Philadelphia Inquirer among other publications.

Helen LaFrance didn’t produce art to become famous but she did become famous. She painted most of her life out of a desire for other people to see things the way she saw them. She painted to share a world where things were neat and lines true and people well groomed. She captured a vanishing world of church picnics, river baptisms, general stores, farmers in plowed fields, and country homes with quilts on clotheslines waving in the breeze.

LaFrance has been quoted modestly saying, “I just do what I do. I thought if I kept doing it, one day I’d do something worthwhile.” And that she did.

Helen LaFrance