8 minute read

An all-new column highlighting church history heroes

FOOTPRINTS OF FAITH

Matt Proctor

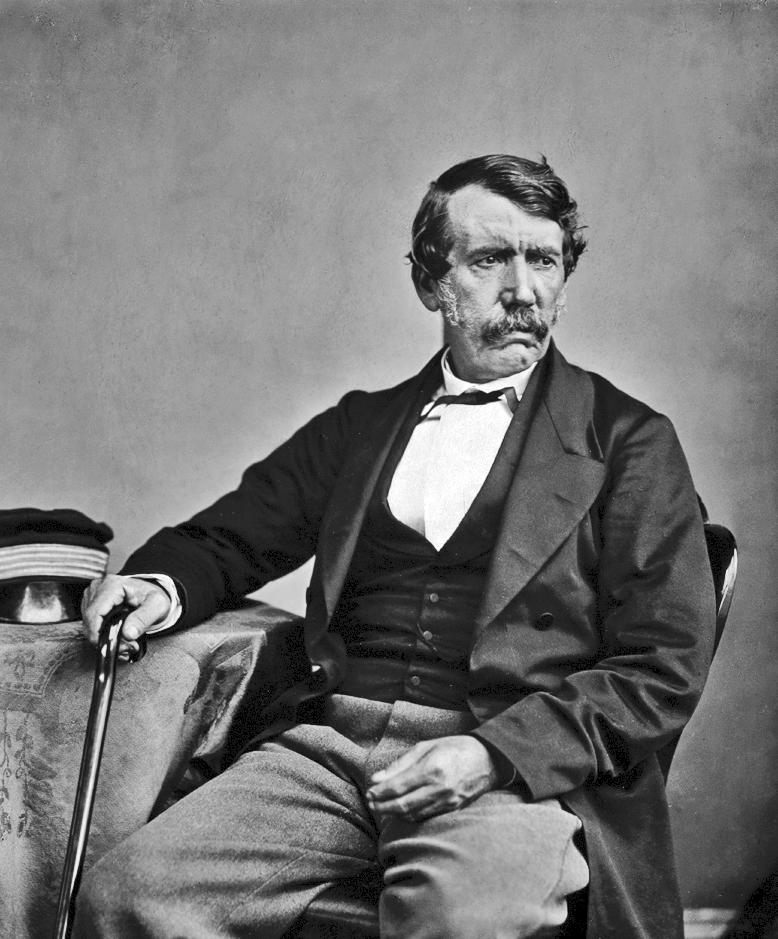

DAVID LIVINGSTONE was the 19th-century Scottish missionary, doctor, and explorer who helped open central Africa to missions.

Editor’s Note: In this new feature, “Footprints of Faith,” each future column will tell the story of a hero from church history, but this first column asks the question, “Why study our Christian ancestors?”

For our 30th anniversary, my wife Katie and I dug our wedding videotape out of the basement, gathered our kids, popped popcorn, and made it a family movie night. They all laughed at how skinny and not-bald I once was.

In the video, you can see I was young—twenty-one years old. I was immature, clueless about women (still am), and had no idea how to love my wife as Christ loved the church. Katie can tell you: our first year of marriage was hard. Though love is blind, marriage is an eye-opener, and Katie and I quickly discovered each other’s flaws. Tension, conflict, discouragement—it was rough going. As I watched, I thought, “How in the world did we ever make it?”

In the video, you can see Katie’s Grandpa and Grandma Bunton. We were married on their 65th wedding anniversary, so we had two cakes at the reception, one for us and one for them. You can see my grandparents, married 63 years. You can see Katie’s parents and my parents, smiling and visiting—both married over 50 years.

That’s how we made it: a heritage of faithfulness. All those couples experienced hard times, but they all rolled up their sleeves and worked through to the other side. So when things got hard for Katie and me, we knew we could do no less. We were now the next chapter in our family’s story, so we rolled up our sleeves.

We had footprints to follow.

The Life-Shaping Power of Heritage

We’ve tried to pass on that heritage. My artist wife painted on our home’s entryway wall a large tree. On the branches hang pictures of our children (and now grandchildren); on the roots hang pictures of grandparents, great-grandparents, and greatgreat grandparents. Over the years, we’ve told our kids the stories of their forebears: • “That’s Great-grandpa Weede. He was a sheep-raising, pickup-truck-driving Iowa farmer. (Yes, a farmer named Weede.) A church elder for forty years, he’d sit in his recliner every night studying his Bible and writing his Sunday School lesson out on notebook paper.” • “There’s your Granny Ruth. Former schoolteacher, strong personality, and the heart of the big Bunton farming clan. (For twenty years, in the ‘occupation’ blank on her tax forms, she wrote ‘matriarch.’) You’ve never met a more servant-hearted lady. She taught the special needs adult Sunday School class until she was 85.” • “That picture is your Mom in high school. Did you know? On the evening she was crowned homecoming queen, she visited a nursing home in her formal dress—just to brighten the widows’ night. When Katie swished in, they ‘oooh’-ed and ‘aaah’-ed, and she stopped to talk with each one.”

Those stories shaped my kids’ souls. So when my daughter Lydia—nominated for homecoming queen like her mama— went Valentine’s Day caroling to the homes of older widows (with a rose for each), I was not surprised. When my daughter Clara became a special needs teacher like her Granny, I was not surprised. And when my sheep-raising, pickup-truck-driving son Carl stood up in church and unfolded a handwritten Bible lesson on notebook paper like his Great-grandpa Weede, I was not surprised.

Our kids knew: they had footprints to follow.

The Bible affirms the life-shaping power of heritage.

When the first-century Jewish believers felt like giving up, the writer of Hebrews painted a big family tree on the wall and then pointed at the pictures—Noah, Abraham, Moses, Rahab—and told stories of resilient faith. His conclusion? “Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses…let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us.”1

Paul wrote, “I serve God as my forefathers did.” Timothy was to “fan [his] flame” by remembering the faith of his mother and grandmother, and when we listen to those who’ve gone before us, we discover Psalm 145:4 is true, “One generation shall praise your works to another.”2

Indeed, down through the ages, believers have found inspiration in the heroes of church history: • George Whitefield’s preaching sparked the 18th-century Great Awakening, but his sermons were sparked by reading 17th-century Puritan Matthew Henry. • In hard times, the great preacher of the 19th century, Charles Spurgeon, leaned on 17th-century John Bunyan, reading his Pilgrim’s Progress over one hundred times. • Where did Elisabeth Elliot, widow of 20th-century martyred missionary Jim Elliot, find strength to stay in the jungle and convert her husband’s murderers? The example of Amy Carmichael, 19th-century missionary who persevered in India 55 years without a furlough.

Those who made history were first made by history. These believers knew: there is wisdom in the “great cloud of witnesses,” and they followed in their footprints.

But why dedicate a column in the Ambassador to these bygone believers?

Expanding Your “Temporal Bandwidth”

We live in a culture afflicted with “presentism”: a constant fixation on the now. Media voices tempt us to focus on the moment—the “hot take,” the breaking headline. We listen to the latest podcast, read this week’s bestseller, binge the newest show, and follow the freshest social media buzz. We forget our historical “family tree,” and today’s Christians often know more fictional television characters than real-life Christian heroes. They can quote Dwight Schrute but not Dwight L. Moody.

But in his book Breaking Bread with the Dead, Alan Jacobs makes a case for reading old, dead mentors: “Personal density is directly proportional to temporal bandwidth.”

What?

He explains: when our culture “traps us in the moment, the more weightless we become. We lack the density to stay put even in the mildest breeze from our news feeds.” To become a person of substance—the solid character and sturdy discernment needed to withstand the moment’s fads and panics—we must be grounded in the wisdom of the past, broadening our “temporal bandwidth.”3 Contemporary voices have something to offer, but those who’ve stood the test of time will help us stand that same test. • By sharing their hard-earned wisdom. Jonathan Edwards’ teaching on God’s sovereignty and Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s on Christian community might deepen your spiritual roots. • By protecting you from error. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” • By stirring your desire to grow. George Muller’s prayer life, Gladys Aylward’s faith, or Martin Luther King’s leadership can challenge you to “up your game.” • By reminding you that God uses broken people. Martin Luther’s harsh tongue, Mother Teresa’s struggles with doubt, and John Wesley’s unhappy marriage graciously remind us: God uses imperfect people. • By inspiring you to persevere in trials. Jonathan Edwards was fired from a ministry, John Bunyan’s wife died young,

Charles Spurgeon suffered crippling depression, and their examples of endurance can shoot adrenaline through your weary soul.

A Snickers Bar and a Book

One of my professors, Dr. J.K. Jones, was a former military policeman, but even tough guys have tough days. He tells of a time early in ministry when he was tempted to give up:

There was a season in the whirlwind of books, seminary, and ministry where I believed I could not go on. Criticism, overwork, and little rest took its toll. One Sunday night, after evening worship and a difficult meeting, I thought I was coming apart. I wondered if this was what it was like when a person had a “breakdown.” I cried and couldn’t stop.

My wife took me and our family over to the home of dear friends...Those precious people reached into their pockets and gave us all the cash they had…and offered these wise words,

“Get out of the area code and let us know where you are.” We loaded the car and drove all night, spending the next couple of weeks in Arkansas with my wife’s parents.

I didn’t think I wanted to go back to that ministry or to that church. My soul was dry, my mind dull, and my heart broken. My mother-in-law knew better than I did what was happening and what was at stake. For several days

I said very little and mostly slept. One morning I heard a knock at the door of the bedroom. I didn’t answer. The door creaked open, and Mom Graham threw me a Snickers candy bar and a book. The only word from her mouth was, “Enjoy.”

I did not open either gift for a while, but slowly I began to eat the candy bar and then turned my appetite to the book.

Mom had found an old copy of The Biography of David

Livingstone.4 I devoured it, reading and rereading words, sentences, and paragraphs. Livingstone’s life of courage, endurance, and character spoke deeply to my soul. It was as if God himself spoke loudly and firmly through that book,

“If Livingstone can persevere, so can you.” After some more days of rest we returned, and our most productive years of ministry in that church followed.5

So in future columns, we’ll explore our Christian family tree. We’ll dig some old videotapes out of the Church’s basement, and as we watch the stories of our ancestors, we’ll remember: we have a heritage to uphold. We are now the next chapter.

We have footprints to follow.

Matt Proctor has served as president of Ozark Christian College since 2006.