8 minute read

LOFTY

When you’re obsessed with sheep, the Yukon’s high country beckons. The tale of one hunter’s quest for a really, really old ram

Advertisement

How do you know he’s old?” I asked.

“It’s easy. Look for a swayback and a pot-belly. Then look at the face. Is he bright-eyed? If he looks kinda out of it, he’s had a good, long life and he’s not getting around very much anymore.”

“He lays around, and thinks about what used to be, but he doesn’t have the zip to do it again.”

“Probably has poor teeth, too. That’s why he might be a loner, and really cranky. Nobody wants to put up with him.”

“Swayback, pot-belly, looks dull in the face—shoot that one.”

I straightened my back, sucked in my stomach, opened my eyes a little wider and smiled brightly. “I can do that.”

“And look for dark horns, broomed and chipped up a bit. That’s a fighter.”

I was remembering those snippets of conversation as spring rolled around back in 2018, gems of wisdom disguised as advice at a Yukon sheep hunters’ gathering. They were terms of endearment, too, for old Dall’s rams, seemingly disparaging remarks, yet directly correlated to admiration.

Soon after, my limited entry sheep permit for zone 7-22 arrived in the mail from the Yukon Department of Environment. That’s the Game Branch, for you other old-timers. I was elated. “This year, we go up there and look for a big old ram. And if we can’t find a really, really big one, we’ll try for a really, really old one,” I said to my then 35-year-old son, Graeme.

In our family, when you say “really” twice, you really, really mean it. Some people add cuss words or swear for emphasis. That’s not the Mennonite way. We just say “really, really,” and add “for sure” if needed.

“Let’s do it,” Graeme replied. “For sure.”

Two weeks later, another letter arrived from the Game Branch: permit rescinded. Oh well, I thought, there are old Dall’s in other places, so I did some research. How old is old for a ram? Surely, Google had an answer for that, too.

I found a study on ram mortality by wildlife biologist Olaus Murie, conducted long ago in Alaska’s Mount McKinley National Park, now called Denali. He collected the horns of 608 rams—all dead, of course—and counted the annuli, or growth rings.

The study included lots and lots of numbers on a chart. They were meaningful. They were all over the page, with no pictures. It was exhausting. Better come back to this some other time, I thought.

Then two weeks later, another letter came. The permit was now “unrescinded.” God works in mysterious ways. And so does the Game Branch, it would appear.

With the hunt back on, I made a strong cup of coffee and revisited Olaus Murie’s ram mortality chart. Aha! There were some words there I hadn’t seen last time. They explained the numbers. The 608 Denali rams had been “extrapolated,” or turned into 1,000 for statistical comparison. So, how many rams per 1,000 lived to be 10? The chart said 439. Another 252 made it to age 11, and 96 lived to be 12. After that, only six lived to be 13, and just three saw the age of 14. Beyond 14? Well, let’s just say this is no country for old men.

In the two weeks allotted for our hunt, we expected to see no more than 100 rams. That was only a tenth of the Denali study’s total, so I simply divided the data by 10 to get a picture of what we might expect to find. Our goal was to get a 13- or 14-year-old. According to my calculations, however, there would only be 0.6 of a 13-year-old and a mere 0.3 of a 14-year-old. That’s not even a complete ram when you combine the two age groups.

Such meagre math didn’t dissuade us, though, so we carried on, turning to social media for hints on finding a worthy ram. I typed in “plenty of rams.” Pictures of a California football team popped up. Clearly this was not the right strategy. We had to do something real—go to where the Dall’s live, and look them over in person.

Early that August, Graeme and I did just that up in zone 7-22, nestled in the Yukon’s Coastal Mountains east of Kusawa Lake. We looked. And we walked. It was hot. The rams were also up high, bands of plentiful bright-eyed youngsters with straight backs, six-packs and light-coloured horns, thin and beautifully tipped out, some above the nose. It was quite a collection of six- and seven-year-olds. But where were the veterans? Had the warm spell in January melted the snow and covered the grass on the winter range with ice, starving them? Was it the late spring? Was it wolves?

After three days, we moved camp to the other side of the zone. We saw lots more of the same until the sixth day. Far in one corner we found them, a group of seven. Very Canadian. One ram, in particular, stood out. It was very special. Not really, really big, but really, really old. He had it all: a swayback, a pot-belly, battered up dark horns, and a face that could sink 1,000 ships. This guy had character. But we let him be.

Why? Commitment issues. It’s generational they say. Leave your options open. Besides, if we took a ram, our hunt would be over. Did we want to go home, sit on the deck for the rest of the season and watch robins hop around on the front lawn? Nope. And so we left the mountains with light packs.

Two weeks later, though, we were back. Rams move around more than you might think, so we were hoping a really, really big and really, really old ram might show up out of somewhere. It’s happened before.

Our second hunt went much like the first one, except that no hunts are ever quite exactly the same. We ran into a grizzly at 50 yards, then encountered another large boar draped over a ripe, half-eaten sheep carcass, its belly distended. Neither of them wanted us, thankfully. Why? Commitment issues. Or perhaps we didn’t smell right.

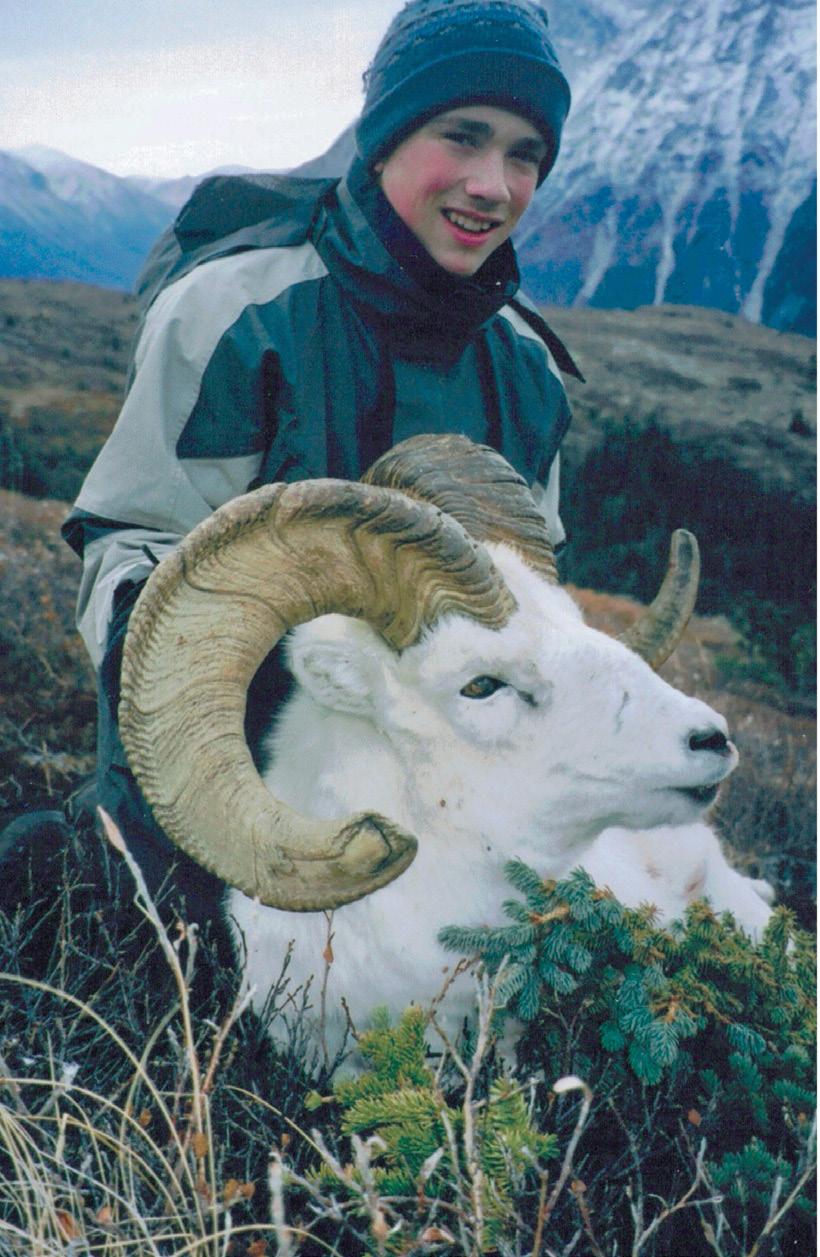

After three days of hunting, we found the group of seven again. Pure white they were against the brown sandstone next to a pale green slope, with dark fir trees below and a turquoise waterway bottoming out the valley. The ram with the dark, broomed-off horns was bedded down on a promontory slightly above the rest. earlier brush leaves he stripped off with his gums. Three front teeth, hollow haunches and little fat were what we found when we dressed him out. What would his last days have been like if my other son, then 16-year-old Jody, had not taken him that October? (See photo above.)

Graeme took a long look through the spotting scope. “Better take him, Dad,” he advised. “That’s a really, really great ram.”

“Let’s do it,” I said. “For sure.”

Graeme planned the stalk: stay above them, out of sight, crawl to the edge of the slope, then take care when you peek over. It took us about an hour, giving me lots of time to think about old rams and memories. I thought of an Ernest Thompson Seton story I’d read as a kid called “Krag, the Kootenay Ram,” about the haunting of a hunter remembering what had been. Then I recalled the ancient 14-year-old ram we watched a number of years earlier, getting by on buck-

Then I contemplated the old ram below us on the rampart, gazing past his cohorts over the vast extended valley framed by forest, cliff and mountain. Was he also in his last summer? I thought of the Dylan Thomas poem “Do not go gentle into that good night,” and wondered how many more years I would walk the alpine trails with my boys, now strapping young men who could carry more and walk just as far as their father.

Of old rams and old men, dignity and endurance, courage and camaraderie, adventure and contemplation, beginnings and endings—all these thoughts pile up and mingle freely in thin air and high places.»

I took off my hat and slithered forward, up and over the large, flat rock just below the rim. “He’s going to be exactly 200 yards below us when we get to that rock,” Graeme said, motioning ahead as he outlined the stalk. Interesting, I mused to myself. Twenty years earlier, I judged the sheep, planned the stalks and called the shots. Now Graeme did. How does that happen?

The wind was behind us, rising with the warm afternoon sun and taking our scent up and over the rams. No hurry here. We both took another look through our binoculars.

“He’s got good weight. Really, really heavy,” Graeme said.

I poked the rifle over the rim, rested my hand under it and waited until Graeme was right beside me with his binos trained on the ram. The crosshairs settled and I gently squeezed.

“Too high, wait.” Graeme’s voice was now my command. “He’s moving to the right. Don’t shoot. Ram in front of him. He’s the one still moving to the right. He’s furthest to the right now, in the clear. Wait, he’s coming up toward us. Wait till he turns. Gotta aim lower, Dad. Okay, now!”

The ram fell, rolled twice and stopped. I scrambled to my feet and was lifted way up into the air and squeezed with a giant bear hug. “I’m so proud of you, Dad! Good shooting—eventually,”

Graeme said, and laughed.

“Just like your old ram in the glaciers,” I said, recall- ing the 14-year-old Dall’s he took in 2001. “Had to shoot over him a couple of times to make him run towards you.” (See photo, previous page.)

We slid down the shale and onto the green slope. “At least 12, probably 13 years old,” I said when we reached the ram. Then I counted the annuli, starting at number three since he was broomed off past the second ring. He was 13, later confirmed by wildlife technicians at the Yukon Department of Environment.

“Twenty-five,” Graeme announced.

“Twenty-five what?” I asked.

“Twenty-five years of us hunting sheep together.”

Suddenly, that very moment, and the hunt, took on all the more significance.

We took a number of days to pack out the ram. Why hurry? The alpine in late August is beautiful, after all, and loved ones appreciate you more if you come home late. Plus, sheep meat is a pleasant burden, and the sight of gnarly old horns on top of a heavy pack never gets old.

The mount of my old ram is now in a place of honour in my home in Whitehorse. Below it is a belt buckle with the engraving “Oldest Ram 2018 taken by a Yukon Fish and Game member,” a plaque commemorating “25 Years of Sheep Hunting, Graeme and Dad,” and a framed picture I took from the treeline of zone 7-22, showing a few scraggly old alpine firs silhouetted against the azure lake far below. “It’s a Group of Seven photograph of where the ram lived,” I tell visitors. The mounts of the two 14-year-old rams taken by my sons are on either side of my Dall’s. Their horns are also dark, battered up and broomed off. One has an old bullet hole near the tip. And in the bleak days of mid-winter, when all is frozen outside and blanketed in snow, my boys and I gather to gaze at the three old rams. We pour a shot of well-aged whisky, sip slowly and cast our minds back to the bright sunshine, high alpine meadows, towering peaks and shimmering lakes far below. Most of all, we consider the old rams, and memories of the hunts. They haunt us still.

They really, really do. OC

YUKONER VERN PETERS HAS BEEN PURSUING SHEEP FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS.

BY RICK BRYNE