10 minute read

CROSSING CANADA FROM COAST TO COAST BY CANOE

By Marianne Scott

Three strokes to starboard. Three strokes to port. That’s how Bert TerHart, 63, paddled his canoe, Kai Nani, across Canada’s rivers, lakes and canals, starting from Gilbert Beach in Steveston, BC, to the Big Shippegan Lighthouse in New Brunswick. “You establish a rhythm of 70 to 80 strokes per minute and with those three alternating strokes, I had the least amount of yaw,” said TerHart. “Paddling an average of 17,000 strokes a day, I didn’t want to increase the distance by zigzagging. In flat water and no wind, I could cover six-to-seven kilometres an hour.”

Advertisement

Along with paddling for roughly 6,600 kilometres, he portaged his canoe for about 200 kilometres and towed it on a two-wheeled cart between waterways for at least another 1,000 kilometres, for a total trek of 7,800 kilometres. Billing his voyage as “One Man, One Canoe, One Country,” he left on April 1, 2022, and arrived on October 1, completing the voyage in exactly six months—or 183 days.

In his early planning, TerHart figured he’d be stuck by weather one day in 20, that one day in 10 would be suboptimal, and that he’d take one day off every 30 days in the trip. He soon learned, however, that he had to make progress every day, come what may. “I ended up with no days off,” he said. “To keep going at an average pace of 40 kilometres a day, some days I had to cover 50 kilo -

Tmetres. It’s a lot like sailing. Sometimes you go at a pace of six or six-and-a-half knots, other days four knots is tops. To make up for slower days, you go as fast and far as you can when the conditions are favourable.

“I’d given myself a 50 percent chance of completing the voyage,” TerHart continued. “I was very lucky with the weather. I could’ve been pinned down in the Great Lakes or the St. Lawrence.”

TERHART’S CANADIAN CANOE crossing wasn’t his first adventure. A life-long sailor, he’d ventured north as far as the Bering Sea, then single-handed his 45-foot OCY sloop, Seaburban, around the globe, leaving Victoria in October 2019, and passing the five great southern capes going east. His goal was to emulate solo navigators who travelled half a century or more ago—without electronic charts or GPS, using only a sextant, paper charts, a pencil and log tables (PY, January 2021). He successfully completed the circumnavigation in 265 days, having sailed 28,820 miles.

I met him at his father’s Victoria home. Jan TerHart, a sturdy 95-yearold Dutch immigrant who still lives alone, has bequeathed his strong genes to his son, who looks like one lean, long sinew after his half-year workout.

I asked TerHart the question he’s heard at least 100 times. “What motivated you to travel the width of Canada by canoe?” His answer is by now wellrehearsed: “I’m a proud Canadian and wanted to follow in the footsteps of the Indigenous peoples, the explorers, cartographers and voyageurs who preceded us across this vast country. And to try to replicate their methods of navigation—no electronic aids, no GPS, only a Cassens and Plath Ultra sextant, an artificial horizon and a compass. I wanted to travel like Champlain, Fidler, Turnor, Thompson, MacKenzie, Hearne, Fraser and the others who mapped Canada. I wanted to try to get some understanding of what it was like to endure some of the things they had to endure.”

TerHart emphasizes that Indigenous peoples had honed their expertise of river and lake systems for thousands of years—without that repository of knowledge, those who formally mapped Canada would have had great difficulty succeeding. It’s that crosscultural collaboration that led to successful exploration and cartography.

PREPARATION FOR THE voyage was extensive. TerHart applied his experience as a former Canadian Special Operations Forces Command soldier responsible for “making everything work” to plan his adventure in detail. First, he had to create a route across the continent that would be safe, minimize portage and reduce the personal towing of the canoe on a two- wheeled cart over roads and through rough terrain.

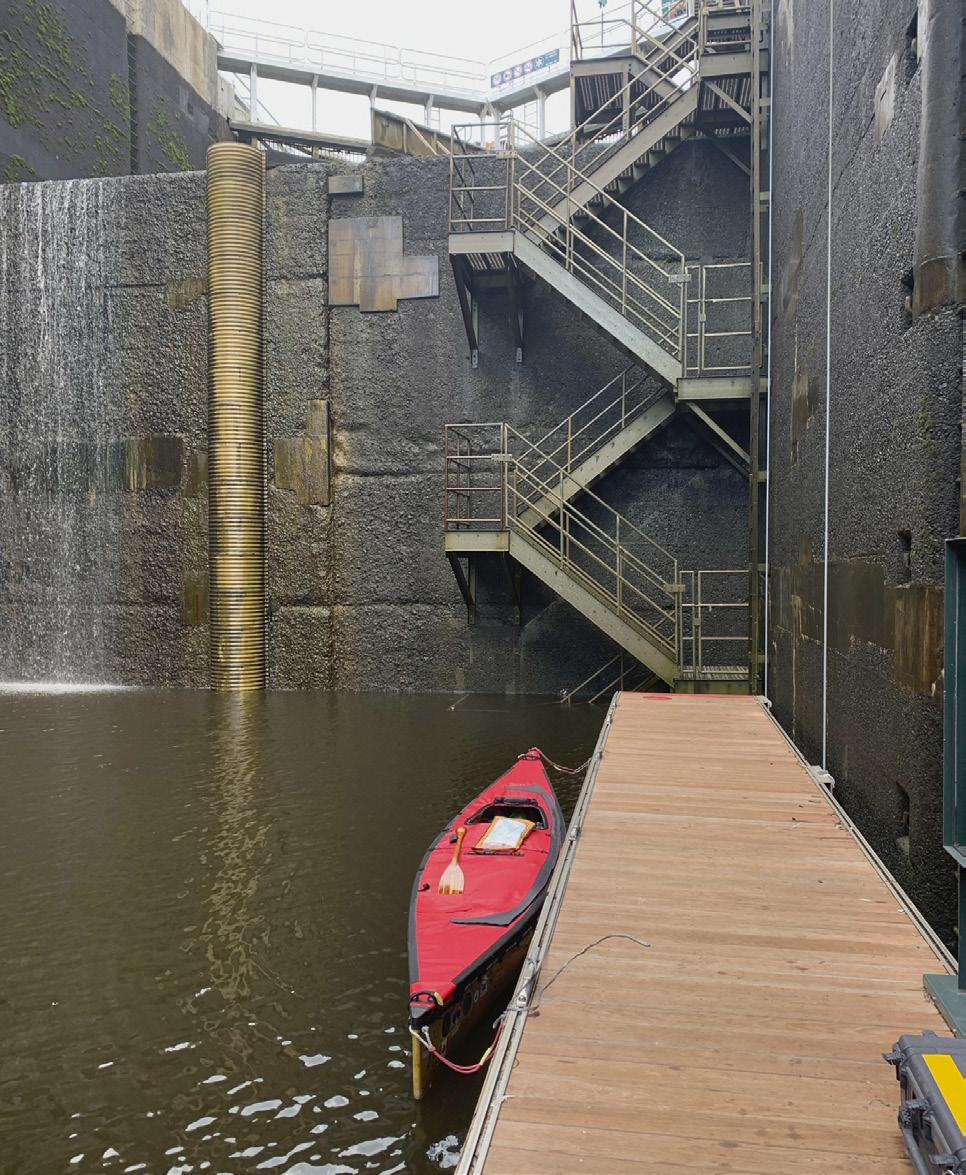

1. In the N. Saskatchewan River. Bert sailed whenever possible which cut seven days off the trip. 2. Bert at the end of his six-month paddle. 3. A PVC riser Bert built keeps water off the deck. A mirror and compass help with navigation.

He perused the maps drawn by the early explorers. “Some of their maps were pure fantasy,” he said. “Peter Pond, for example, never travelled beyond the Athabasca region but he drew fictional maps to the Arctic.” But by the end of the 18th century, explorer and fur trader David Thompson’s maps were very accurate. He, too, used a sextant to find his position.

“I created one strip chart across Canada,” he continued. “And since the maps and charts from Google’s satellite pictures aren’t always accurate and maps of the terrain I covered weren’t uniformly available, I used software to create my own maps from Canadian topographic data.”

I wondered whether his route would roughly follow the Trans-Canada Highway. By comparing the two itineraries, it’s clear that the Trans-Canada is considerably straighter than the waterways TerHart had to follow—his paddling route, especially through the Rocky Mountains, Alberta and Saskatchewan skewed farther north following the rivers coursing through the vast Canadian landscape.

TerHart considered his six-week trip through BC the most physically gruelling. “I paddled a series of connected rivers, of which only two days were downstream,” he said. “I started with the upstream Fraser watershed, then the Similkameen watershed, followed by the Okanagan River and eventually entered the Columbia.” Along the way, he towed the canoe and its contents—about 200 pounds—for roughly 650 kilometres. “Everything seemed ‘uphill’ through British Columbia,” he said.

As it was April, he encountered snow and sleet. It was only when he reached the Saskatchewan River near the Alberta border that things improved. “The Saskatchewan touches a good part of Canada,” he said. “It reaches to Winnipeg, or Lake Winnipeg, a choice made by the weather.”

CHOOSING THE RIGHT canoe was crucial, with durability and weight being the major considerations. TerHart tested several and ended up with a 16-footer he called Kai Nani—a Polynesian term meaning “harmony between wind and water.” The Quetico model is manufactured by Souris River Canoes, in Atikokan, Ontario, a small town that proclaims itself as the “Canoeing Capital of the World.”

The canoe is not completely open to the elements. TerHart selected a spray deck with a single opening at the seat, as well as a zippered cargo hatch. Custom-made by North Water in Vancouver, the 1,000D PVC coated polyester spray deck loops 2.5 inches over the canoe’s gunwales, and adds a pocket for a spare paddle. It certainly keeps waves from sloshing over the bow but doesn’t keep out all rain. “There were times during heavy downpours I had to bail,” said TerHart.

His towing harness is made by Ski Pulk; TerHart significantly modified the harness so that it included six points of adjustment to minimize stress on his body.

The paddles he used for up to 14 hours a day were almost as important as the canoe. He trained with seven custom-made paddles testing for lengths and shapes that would best suit his arms and fitness level.

The straight paddles ranged from 61 to 62.5 inches and were built by wellknown custom paddle maker Bruce Smith in Fergus, Ontario. The bent, spiralled paddles TerHart used most, measuring 52 to 54 inches, were constructed by the XY Company, also located in Atikokan, Ontario.

WHAT TO WEAR for both winter and summer while paddling? The most important thing was to stay dry and warm. “Getting wet in the cold is very difficult and can lead to hypothermia,” TerHart said. “So I spent money on the outdoor clothing made by California-based KUIU. I had to wear the right things while paddling or walking as I never had a place to dry clothes. So even during downpours when I had to bail two or three gallons out of the canoe, I’d still be dry…”

During the summer heat, he always wore a hat and was religious about using sunscreen, especially on his ears.

Always looking for efficiency, TerHart added a sail to his canoe using a completely collapsible rig and sailing whenever possible,. “I used short sections of carbon fibre tubing as mast,” he explained in an email. “I customized the sheeting arrangements including being able to reef the sail from my seat. I could sail from 60 to 180 degrees in winds to 15 knots. Top speeds when surfing down waves were above seven knots while average sailing speeds were easily above five knots. I sailed on anything I could paddle on, including through rapids. Sailing saved me at least seven days.”

His towing cart, which TerHart nicknamed “Karta,” weighed a hefty 36 pounds, but like all his curated equipment, it was essential. TerHart towed the canoe and its contents along roads and through woods where sometimes he had to hack his way through dense underbrush with an axe and bucksaw. The Seattle Sports All Terrain Kayak/ Canoe cart is rated at 300-pound capacity, folds and stores in a bag.

FINDING CAMPSITES WAS one of his greatest challenges. High banks, rocky embankments, muddy shores and private property restrictions could prevent him from finding a safe place to sleep. Many of the earlier Indigenous settlements that might have welcomed him had disappeared over time, but some remained. “I was well received by Indigenous folks and they were pleased that someone was following the explorer routes,” he said. “I was always allowed to camp on reserve land, offered help, food and rides.”

Locations could be deceptive. One day he pulled up at someone’s property and walked to the house to ask permission to put up his tent. “No one was home,” said TerHart. “I decided to pitch the tent anyway. A guy shows up later in an ATV. I introduce myself and my mission. He’s leery, can’t see the canoe and I’m a stranger in weird clothes in the middle of nowhere. If you travel alone, people wonder if you’re a sociopath. He goes inside, returns and has switched from leery to welcoming. His wife has googled me. He comes back with food and offers a shower. I stay the night in my tent. Just one of many great experiences.”

TO FIND THE right tent, TerHart bought five and tried them out at his home on Gabriola Island. He chose the X-Mid Pro two-person tent made by Durston, a company that sells ultralight tents and backpacks—his tent weighed a mere 800 grams (“I have jeans that weigh more,” TerHart joked). He described the tent as his refuge.

In a Facebook post, he wrote: Rain or shine, every day ended the same way. Exhausted and soaked in sweat… as soon as I stopped, I’d begin to cool down. Always the first order of business was shelter. Pitch the tent immediately to retain what warmth was left of the last hours’ efforts, escape the inevitable cloud of mosquitoes and black flies, or beat the rain.

BUGS, INCLUDING MOSQUITOS, black flies and horseflies were constant, attacking relentlessly despite his wearing bug-resistant gear. “Fortunately, I’m immune to them and my body doesn’t react to bites,” he said. He also saw much wildlife. “Cougars, bears, caribou, every kind of deer, coyotes, raccoons, river otters, beavers everywhere. Geese, of course, and swans, ducks, even pelicans.”

Taking in enough food, especially protein, was essential. TerHart estimates he burned about 7,000 calories a day. He’d brought 20 days’ worth of sustenance not knowing where he’d find food along the way. Oatmeal, pasta, dried meat, bread, energy bars and tomato sauce were staples.

Not wanting to add the weight of bottled water, he’d invested in a water filter which kept him hydrated. He used microfibre cloths and no-rinse soap to keep clean. He charged his iPhone with a battery that was charged in turn by a 20-watt solar panel fixed onto the canoe’s stern.

TerHart usually launched his day around 04:00. He says he was shocked at the workload of moving every day and that it was mentally exhausting too. “There’s no relaxing evening with a movie or Netflix, no weekends off. You have to move, no matter what, for 12 to 14 hours and then you still wonder, ‘should I have gone further? Will the weather throw me a curve?’ And you’re on your own, not lonely, but alone. No one to bounce ideas off, no one to help you decide the right course.”

When he reached the mighty St. Lawrence River, he was astonished that as far up-river as l’Île d’Orléans, the tide reached 18 feet. With the ebb and wind at his back, his speed-over-the-ground increased markedly—paddling against the tidal currents was impossible.

On his first day paddling the St. Lawrence, as TerHart recounted on his blog, he’d spied a breakwater about four kilometres ahead. The tide was low and he was separated from the shoreline by wide mudflats. As the tide turned to flood, a wind suddenly rose and TerHart got stuck in a mudbank. “Two hours and nine round trips to the riverbank was an experience I was determined not to repeat,” he blogged. Knowing he had two daily opportunities to move downstream on the ebb, he adapted his schedule, leaving early and paddling as hard as he could between man-made river-side structures like quays and ferry crossings.

EVER CLOSER TO touching the Atlantic Ocean, TerHart’s discipline and persistence carried him to Campbellton, New Brunswick by September

19 and to Bathhurst four days later, where he experienced some of Hurricane Fiona’s left-over power. When he placed his hand on the peeling white paint of the Big Shippegan Light, he was greeted by his brother Jan, and sisters Stella and Leah. No fanfare, no fuss, no press.

Since that marvelous day of arrival, October 1, TerHart has reflected on his intrepid voyage, on the hardships and the kind people he met along the way. On their stories and their gifts, which he says, “brought him to his knees.” He’s wondered whether these six months have changed him—he believes he’s a better Bert, but fundamentally remains Bert nonetheless. On Facebook, he pondered, “How one comes to gamble their life on a couple of litres of epoxy and a few gossamer strips of cloth I know not. I did, and I can’t.”

HE PLANS TO write a book about his Canadian crossing, and another sailing trip is playing in the back of his mind. A group of eight uninhabited volcanic islands, the Islands of Four Mountains, in the Aleutians may need exploration…