38 minute read

Imagining Florestan: An Attempt to Recover the Lost Aria of 1805 by Will Crutchfield

Beethoven’s involvement with his only opera produced three distinct scores on three occasions in Vienna:

• The 1805 premiere as Fidelio, the work revived in the present production • The 1806 revival as Leonore, with revisions and abbreviations • The 1814 revival as Fidelio, extensively re-composed, that has remained in repertory.

As though this were not enough, the composer left us four distinct overtures; the “extra” one, published as Op. 138 and now confusingly known as “Leonore No. 1,” was most likely written for a projected but unrealized Prague production in 1807 or 1808. It is a lot of music, yet every bit is of interest.

One important bit unfortunately went missing: the principal tenor aria of Beethoven’s 1805 opera was literally destroyed when the scores of it were cut up so that some pages could be recycled in the version of 1806. The pages lost on the cutting-room floor included a significant passage – a solo in F Major with obbligato flute as the imprisoned Florestan recalls happier days with Leonore at his side – of which no trace remained in the other versions. Also lost was the first version of the aria’s slow movement, “In des Lebens Frühlingstagen,” which was different, likely quite different, from the ones we know.

The paper trail of the dismembered scores tells us beyond doubt that these movements were present in the 1805 Fidelio, but the only evidence we have for their musical content comes from the composer’s sketchbooks, where he recorded multiple drafts of their melodic lines. For the current Beethoven anniversary year, Opera Lafayette invited me to edit these drafts and try my hand at devising an orchestral score to accompany them. The idea is to let audiences hear for the first time Beethoven’s original conception of the aria, even if we cannot hear the way he himself orchestrated it. Doing this meant also picking up the thread of a long-running musical detective story that scholars have been investigating for more than a century: just what happened, and when and why, to this problem aria? What follows is an account of that mystery and the process of developing the score heard at these performances.

I - The shape of the scene

Florestan’s soliloquy in the dungeon is laid out on a plan that remained intact in all three versions of the opera, though the content was significantly different in each. Its components: an instrumental prelude, an expansive recitative, and a grand aria in two parts – a slow “cantabile” movement followed by a faster one.

This scheme had been standard for the principal solo of a star singer since roughly the youth of Mozart. The prelude was an optional component; long ones were typical if the character was alone on stage, while if others were present, the prelude might be short or even absent. The key element was the two-tempo aria, which from the middle-18th century had gradually displaced the venerable aria “da capo.” Familiar examples by Mozart are Donna Anna’s “Non mi dir” (Don Giovanni), the entrance aria of the Queen of the Night (Die Zauberflöte), and – especially important for Beethoven – Fiordiligi’s “Per pietà, ben mio, perdona” (Così fan tutte). This form served opera for over a century: under Rossini’s hands the final allegro mutated into what we call a “cabaletta,” and was still being used by Verdi and his compatriots up to the early 1860s.

Leonore/Fidelio holds two such arias, those of the principal couple. Leonore’s was revised, but always by refining and concentrating the musical ideas present from the start. Florestan’s had a more complex history, which we can trace from Beethoven’s multiple sketches through to the 1814 Fidelio.

For grasping that history, the best starting point is Sonnleithner’s 1805 text for the aria (based closely on Bouilly’s libretto for Léonore, ou L’Amour conjugal, discussed in the main program note about the opera).

In des Lebens Frühlingstagen Ist das Glück von mir geflohn! Wahrheit wagt’ ich kühn zu sagen, Und die Ketten sind mein Lohn. In the springtime days of life Joy has fled from me. I dared boldly to tell the truth, And chains are my reward.

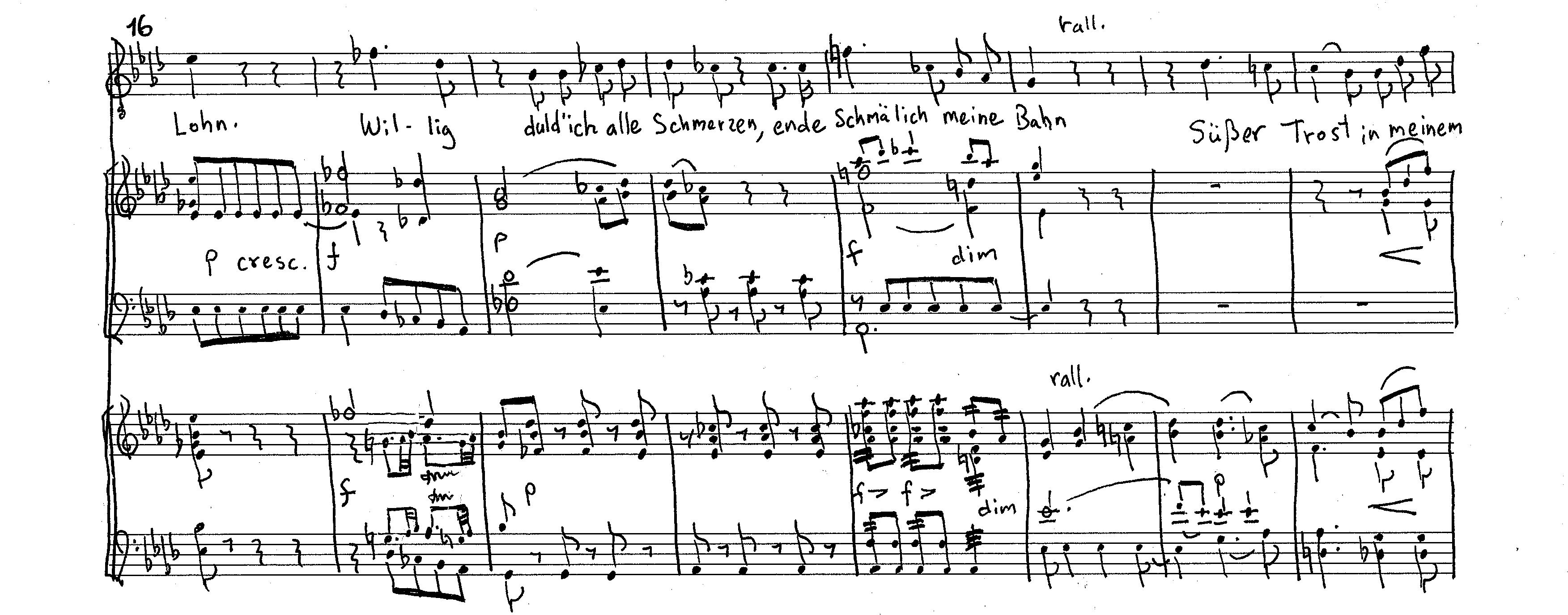

Willig duld’ ich alle Schmerzen, Ende schmählich meine Bahn. Süßer Trost in meinem Herzen: Meine Pflicht hab ich getan! Willingly I bear all sorrows, And take my path to a dismal end. Sweet consolation in my heart: I have done my duty.

[er zieht ein Bildnis aus dem Busen] [he draws a portrait from his breast]

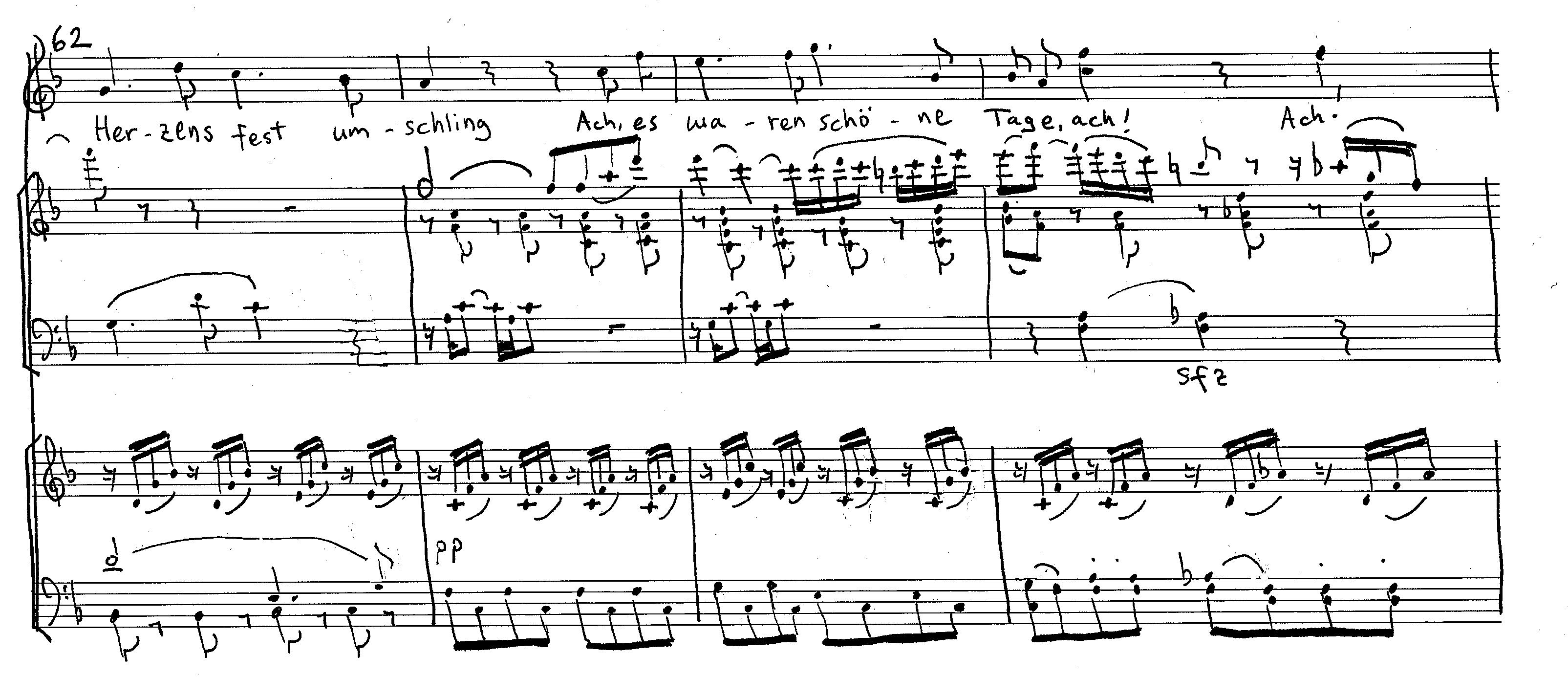

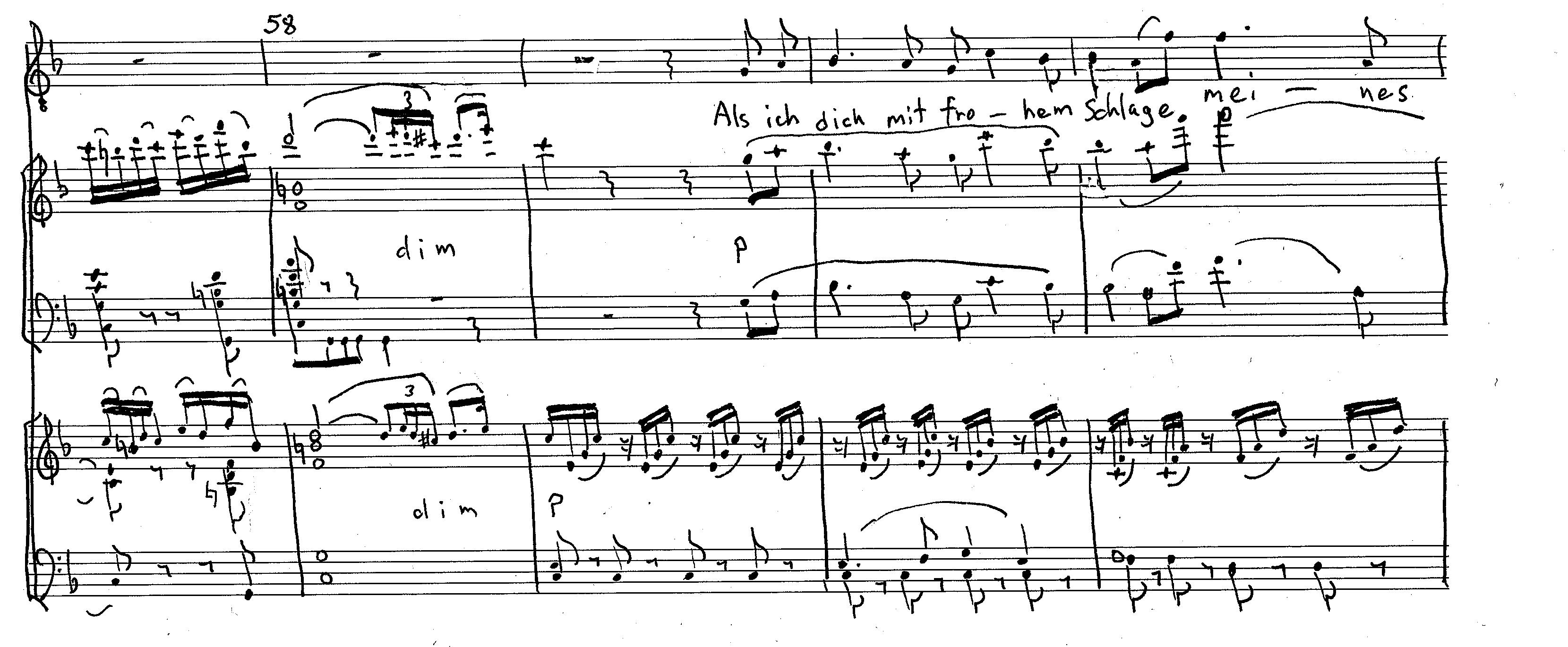

9 10 11 12 Ach, es waren schöne Tage, Als mein Blick an deinem hing, Als ich dich mit frohem Schlage Meines Herzens fest umfing. Ah, those days were fair When my glance hung upon yours, When, with heart beating for joy, I held you fast.

13 14 15 16

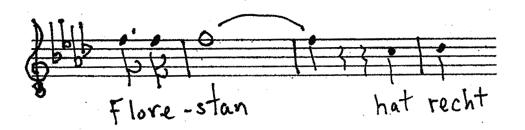

Mildre, Liebe, deine Klage, wandle ruhig deine Bahn, sage deinem Herzen, sage: Florestan hat recht getan.

Soften, love, your lament, Go your way in peace, And say, say to your heart: Florestan has done right.

Of these four balanced quatrains, the first two are familiar to opera-goers who know the 1814 Fidelio, but the last two are not. They were replaced, in the end, with a new text by Georg Friedrich Treitschke, in which Leonore appears not as a memory but as a guardian angel leading Florestan to freedom in the afterlife. In the first two versions of the opera, the quatrains had been symmetrically disposed: two for the slow movement and two for the fast. And in 1805 – but not in 1806 – the last pair was also evenly divided: one quatrain for the lost F Major passage with flute (the “Flötenarie,” as Beethoven sleuths have been calling it for more than a century), and one more for a concluding section in f minor, the key of the prelude with which the scene had begun.

When the “Flötenarie” was cut out in 1806, its poetic text did not vanish; instead, the whole third quatrain was grafted into the f minor conclusion. It was laid over the music originally destined for lines 13, 15, and 16 (14 seems to have been skipped the first time around), which were thus left to be heard only at what would have been their repetitions (where line 14 finally takes its place).

The chart below summarizes the contents of the scene in the three versions of the opera (there was also an intervening stage between the 1805 and 1806 versions, discussed later).

1805 [Fidelio] 1806 [Leonore] Prelude: Grave 4/4, f minor Prelude (revised) Recitative Recitative (revised) Aria, first part: Adagio 3/4, A-flat major (lines 1-8 of aria text, music lost except first two bars) Aria, first part: Adagio (revised; lines 1-8 of text). Aria, second part: Tempo indication unknown, 4/4, beginning F Major (“Flötenarie,” lines 9-12 of text, music lost), finishing f minor (lines 13-16 of text, partly retained in 1806) Aria, second part: Andante un poco agitato, 4/4 f minor (final portion of the 1805 movement, revised; lines 9-16 of text)

1814 [Fidelio] Prelude (again revised) Recitative (largely rewritten) Aria, first part: Adagio (again revised; lines 1-8 of text) Aria, second part: Poco allegro, 4/4 F Major (text and music entirely new)

Ferdinand Ries

The first question here is “what allegro?” Most have assumed that Röckel meant the familiar “Poco allegro” of the 1814 Fidelio - which may be correct, since in correspondence with later biographers he ascribed that passage to the wish of Giulio Radichi, the 1814 Florestan “to be applauded” at the end of his scene. Tusa, knowing that Röckel had performed the F minor “Andante un poco agitato” in 1806, hypothesizes that this movement was meant - but “major” for “minor” is an odd mistake for a musician to make at random. A third possibility is that Röckel meant the very passage we are discussing, the “Flötenarie.”

II - The backstory

The best studies of the lost aria are contained in a series of papers published by Michael C. Tusa and Helga Lühning in the 1990s, of which the most comprehensive are:

Michael C. Tusa: The Unknown Florestan: The 1805 Version of “In des Lebens Frühlingstagen.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Summer, 1993)

Helga Lühning: Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Arie des Florestan. In: Festschrift Christoph-Hellmut Mahling zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. Axel Beer. Tutzing, 1997

These lay out the information at our disposal in full detail (including fresh discoveries), along with transcriptions of many of the relevant passages from Beethoven’s sketches. I recommend them to everyone with an appetite for musical archeology and thank both authors for making the task far easier for anyone following in their footsteps.

Published discussion of the mysterious aria, however, began more than 150 years earlier, when Beethoven’s sometime pupil Ferdinand Ries (1784-1838) interviewed Joseph August Röckel (1783-1870), the tenor who sang Florestan in the 1806 revival. Röckel was the only new member of the cast, having been recruited to replace Carl Demmer (1766-1824), who had sung – and apparently been a bit of a problem – in 1805. The Röckel/Ries account was published in 1838; here is its musical portion in full (author’s translation):

tenor who otherwise did not want to perform. In the first version, Florestan had to hold at the end a high F for four whole bars adagio, while the instruments slowly faded away. This the tenor could not do, and so, probably in the revision, the portion of the Adagio that returns to the tonic F Major or f minor was left out, since it now moves from A-flat major, 3/4 adagio, directly into an allegro, 3/4 [sic] in F Major. Herr Röckel narrated the matter thus to me; he also assured me that he still possesses the vocal part in Beethoven’s own handwriting.

This is a clear and straightforward narrative; the only trouble is that almost everything in it is demonstrably wrong. But why? Lühning speaks for many when she says that the tenor, three decades after the premiere, “obviously scarcely knew any longer what he was talking about” (“offenbar wusste [...] kaum noch, wovon er sprach”). Most scholars have agreed that the account is too unreliable to be of much use for tracing the history of the piece. In the course of working through the aria, though, I came to a different conclusion: that Röckel most likely knew exactly what he was talking about, but was misunderstood by Ries on a crucial point from which almost all the other errors flow – and that those surface errors may conceal some important clues to the sequence of events in question.

Three things must be borne in mind. First, we are reading Ries’s paraphrases and interpretations of what Röckel said about a score that Röckel had seen but Ries had not. Second, when we ask “what was the aria in 1805?” we are really asking two questions: what did Beethoven put into production (having scores copied and orchestral parts made), and what was actually performed. It is possible that these were not the same. Third, we must recall the intermediate stage of revision between the 1805 performances and Röckel’s appearance on the scene, mentioned above but not yet discussed. Beethoven drew up a sketch/memorandum for re-casting the scene in various ways, including the reduction of the aria to just a single movement. The pared-down 1806 version of the Adagio may have been written while this plan was in Beethoven’s mind.

Details are given below where they are relevant to the mystery, and we will return to Röckel and Ries point-by-point, after first reviewing what we know from the manuscripts and sketches.

III - What is known and what must be guessed

Our knowledge of the lost 1805 aria comes from two types of evidence. The first is the surviving shreds from a couple of dismembered copies of the original score. One of these (known as “Autograph 5” in a collection of Beethoven material found today in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin) was used by the composer in the revision process. He marked the 1806 adjustments to the prelude and recitative directly over the 1805 readings, which is why we still have both versions of those passages today (though they have to be disentangled from still further revisions made for the 1814 prelude!). Then a new copy takes over for the aria proper - but the very first page of the old one was left in, because the end of the recitative was written on the other side of the same sheet. This isolated page tells us two important things: first, that the aria had an instrumental prelude in 1805 (this was deleted in 1806); second, that there was a part for solo flute.

Even though all we see of it is two empty bars, it proves that some version of the “Flötenarie” had been present, because the flute has nothing to play elsewhere in the aria. (Its line vanishes from the score pages written afresh for the revised version.)

Then there is a score possibly prepared for the unrealized Prague production, and in any case located there today. Once again part of an 1805 copy was left in place - this time, pages from the final f minor section, including some in which the music, but not the text, was the same for 1805 and 1806. A second hand adjusted the words, but the first layer proves that the f minor section originally contained only the fourth quatrain of verse. That proves in turn that this manuscript as well once contained the “Flötenarie,” and confirms that it was – in 1805 as in the sketches – the home of the third quatrain. (The

Prague copy also allows us to see some smaller revisions towards the end of the f minor section, including two bars that were left out in 1806.)

That is not much to go on, but it does at least leave us certain that the “Flötenarie” and some different version of the Adagio were actually present in the score prepared for 1805, not just in the sketches. And what do the sketches tell us?

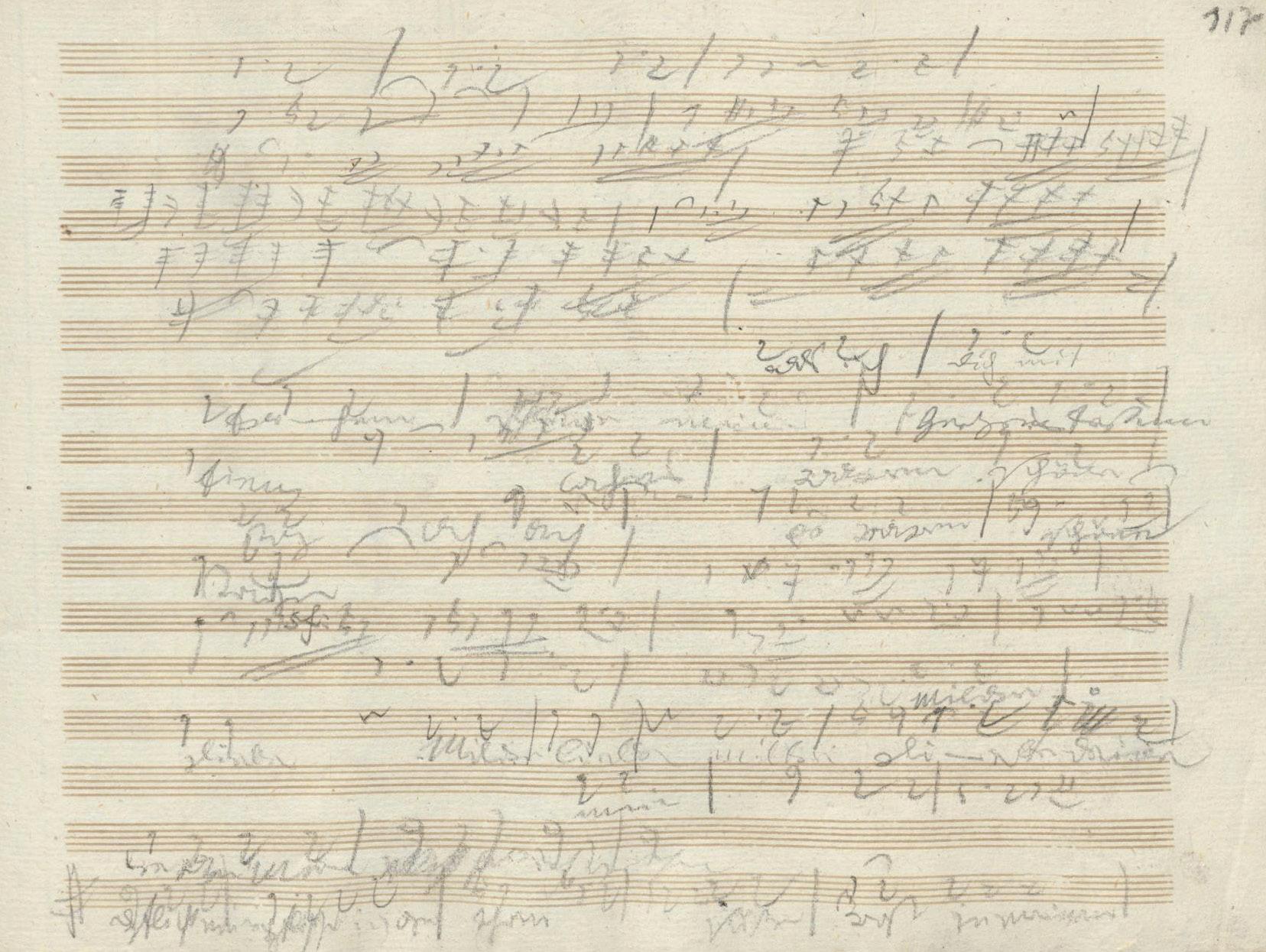

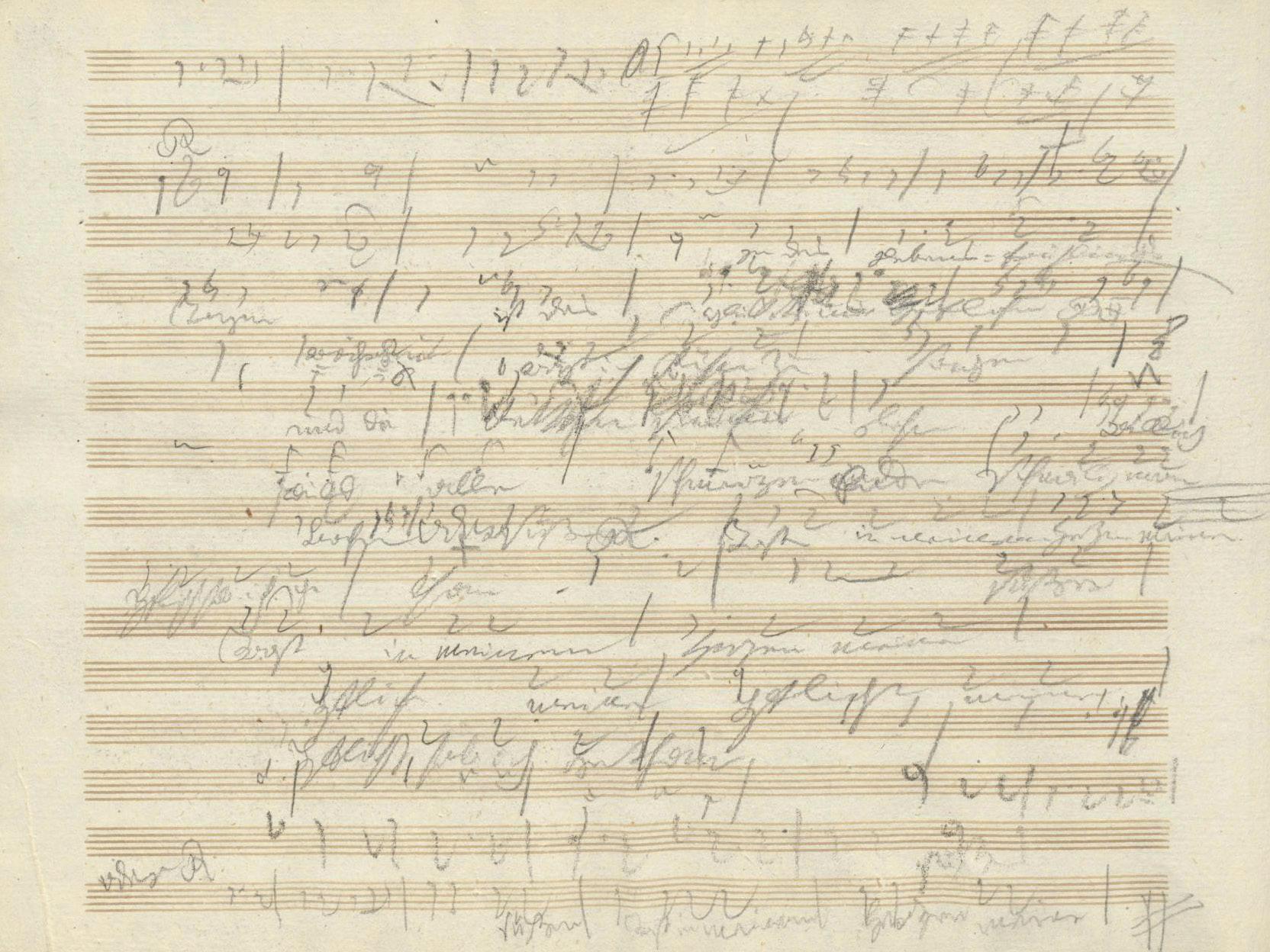

The main source for the early versions of the opera is the so-called Leonore Skizzenbuch, 346 densely filled pages now bound together and housed in the same Berlin library. This contains multiple passes over the Florestan material and many isolated fragments, documenting many ideas that were incorporated into the eventual scores alongside many others that were not. Amidst many uncertainties, this much can be said:

• Throughout the sketchbook, up until a few pages appended at the end reflecting Beethoven’s work after the 1805 performances, there is a clear and unvarying plan for the scene: Prelude; recitative; Adagio aria (almost all sketches in 3/4 time and A-flat Major); second movement in 4/4 time beginning in F Major (“Flötenarie”) and finishing in f minor.

• The Adagio is sketched bewilderingly many times, but several important phrases found in its newly-written 1806 score do not appear at all in the sketchbook, while on the other hand certain events present in nearly all the sketches fail to reappear in that score.

• The drafts for the “Flötenarie,” though they are often duplicative and sometimes contradictory, contain at least twenty-eight continuous bars of vocal and instrumental melody, plus a further passage that describes, in various alternative ways, the transition to the f minor section and its beginning. (A bit past that beginning, as we know from the Prague copy, the 1805 and 1806 versions tally up, with only slight revisions, so we no longer need to rely on the sketchbook.)

Already we are face to face with a glaring contradiction of the Ries/Röckel narrative: they say the original version ended at the Adagio, and every bit of concrete evidence tells us otherwise.

IV - What happened?

Both Ries and Röckel were close to Beethoven over a span of many years, and both were expert musicians. That is self-evident for Ries, who had his own strong career as a composer and virtuoso pianist. It is less to be taken for granted in the case of a tenor, but Röckel was not just a tenor; at various times he also worked as a copyist, chorus-master, and impresario, and he came from a large clan of prominent musicians. All three of his sons became composers; his sister Elisabeth (also a singer) may have been the “Elise” of Beethoven’s most famous short piano piece. Ries, meanwhile, ought to have been our most informative witness on the transformations undergone by the proto-Fidelio, since he had come under Beethoven’s wing as pupil, copyist, and companion early in 1803. But the same French invasion that soured the opera’s 1805 premiere had driven Ries out of Vienna two months earlier, for fear of being conscripted into the army. He did not return until 1807, thus missing the entire interlude between the two scores and the rehearsals and performances of both.

Still, there is no apparent reason either man should have been an unreliable narrator, so it is worth asking line by line why their account could have gotten so much so wrong. It is repeated here in numbered fragments (following Tusa’s example), this time accompanied by Ries’s original German (with modernized spelling). Each is followed by some new speculations on its problems.

[1] Florestan’s aria, No. 11 (at the beginning of the second act), had in the first version concluded with the Adagio in 3/4 time. Die Arie Florestans, Nr. 11 (Anfang des zweiten Aktes), hatte bei der ersten Bearbeitung mit dem Adagio im 3/4 Takt aufgehört.

The numbering was different in 1805 (No. 13, third act), but that is unimportant; Ries was addressing readers who knew the eventual 1814 Fidelio. What he says about it obviously cannot be true if by “first version” we mean the score prepared for 1805, in which the presence of both the “Flötenarie” and the f minor ending are securely confirmed. As Tusa observed, Ries’s assertion could well be true of the first version known to Röckel – if he was shown Beethoven’s above-mentioned interim plan and assumed it to be the original. But as we will see next, Röckel probably knew more, and it is possible that he is telling us something not about the first composed version but about the first performed one.

[2] The Allegro in F Major was added only later by Beethoven for a tenor, who otherwise did not want to perform. Das Allegro in F dur wurde von Beethoven erst später für einen Tenoristen, der sonst nicht auftreten wollte, hinzugefügt.

The first question here is “what allegro?” Most historians have assumed that Röckel, three decades after the events described, was confusedly imagining the familiar “Poco allegro” of the 1814 Fidelio. But if so, how could Ries have thought it had anything to do with the story he was drawing from the veteran tenor? Tusa, knowing that Röckel had in fact performed the f minor “Andante un poco agitato” in 1806, hypothesizes that this movement was meant – but “major” for “minor” is an odd mistake for a musician to make at random. A simpler explanation is that Röckel meant the very passage we are discussing, the “Flötenarie.”

If that has not occurred to everybody, it is probably due to a long history of calling the passage “the Moderato,” as Gustav Nottebohm did in the first extensive study of the “Leonore sketchbook” over 150 years ago. We do not know what tempo marking the aria’s second movement might have had in 1805. The heading “andante un poco agitato” for the f minor part dates from 1806 when it stood alone. As Tusa points out, the sketches for the missing F Major section have only one hint of a tempo indication, the abbreviation “Moder” at the start of one early fragment.

Naturally enough, there evolved a habit of discussing the lost aria as being in three movements (Adagio, Moderato, Andante). But in fact “moderato” was not generally used as a free-standing tempo indication. Beethoven employed it that way on only seven occasions in his entire output, and in almost all of those, there is a previous tempo in the same meter that is being “moderated.” He used it quite often, though, as adjective after another indication – most often “allegro,” which was also the default tempo for the second part of the standard two-part aria.

Allegro and andante were not as far apart in the beginning of the 19th century as they later became; it had only been a couple of generations since composers of the late Baroque era could use the terms to modify one another (“allegro andante”). In the sketches, the f minor material seems to be a straightforward continuation – in the same meter and tonality, with shared melodic components – of the material in F Major. No sketch for the transition indicates a change of pace. An allegro held back by “moderato” and an andante pressed forward by “agitato” could easily be one tempo described in two ways, according to musical and dramatic character.

All this is to explain that the Röckel/Ries mention of “the Allegro in F Major” could easily mean that “the Moderato” was actually designated by something like “allegro moderato” in its finished score, or it could simply mean “the second movement,” identified by the generic designation of “allegro” – but could logically refer to the “Flötenarie” either way.

This speculative explanation still leaves the problem of “the Allegro” supposedly being added at the insistence of a tenor who “did not want to perform” without it. Again, we know from the sketches that this cannot be true. Tusa speculates that Röckel was being coy with his interviewer, and that the demanding tenor was himself – rejecting Beethoven’s proposal for a single-tempo aria and insisting that at least part of the final movement be restored. This is by no means impossible, but a somewhat simpler alternative can be suggested after we consider the remaining points in the account.

[3] In the first version, Florestan had to hold at the end a high F for four whole bars adagio, while the instruments slowly faded away. Bei der ersten Bearbeitung hatte Florestan am Ende vier ganze Takte Adagio das hohe F auszuhalten, wobei die Instrumente sich langsam verloren.

[4] This the tenor could not do, and so, probably in the revision, the portion of the Adagio that returns to the tonic F Major or f minor was left out, since it now moves from Ab major, 3/4 Adagio, directly into an Allegro, 3/4 [sic] in F Major. Dies konnte jener Tenorist nicht und so ist, wahrscheinlich bei der Umarbeitung, der Teil des Adagios, der wieder in den Grundton Fdur oder F moll fällt, weggeblieben, indem es jetzt aus As dur, 3/4 Adagio geradezu in Allegro 3/4 F dur fällt.

“Allegro 3/4” is presumably a mere typographical error; the movement in the score “now” (i.e., ever since 1814) is in 4/4 time, as was the original second movement. The “hohe F” has flummoxed everyone. First of all, no sketch and no known finished version of the aria suggests any such thing, nor indeed any extraordinarily long note whatever for Florestan. Second – and this has not been taken into account before – the description is highly suspect on its own. The word “adagio” is ambiguous – it can be either

an adjective or a noun, and Ries capitalizes it either way – but the narrative clearly places the supposed note in the Adagio, i.e. the A-flat Major aria, and this is nearly out of the question. Even at the very fastest metronome mark ever set down by Beethoven for any adagio movement (and it is a controversially fast one), such a note would last fully twelve seconds. The ability of a tenor to hold an upper F so long, while not unknown, is rightly considered phenomenal, and there is no known example of any composer prescribing such a feat. Moreover and finally, no sketch for this Adagio gives any suggestion that it might “return to the tonic” established in the scene’s instrumental prelude.

Yet the scene did indeed modulate back to its opening key, and there is a clue in the phrase “am Ende [...] wobei die Instrumente sich langsam verloren.” The instruments have no occasion for such an effect in the Adagio movement, but they are given that exact instruction (“sempre perdendosi”) at the very end of the f minor segment:

Still, there is no long note – neither in the sketches for this passage, nor in the Prague copy derived (at this point in the piece) from the 1805 version, nor in the one that served Beethoven for his revisions in “Autograph 5,” nor in the 1806 score as published in 1810. But if we suppose that the story had some basis in fact, we might speculate that Beethoven had an idea not hinted in the sketches, but musically and vocally plausible. The clarinet and bassoon are indeed holding a long F at the moment the instruction appears. Might Florestan have joined them? Did Röckel perhaps say, or mean to say, “Taktschläge” rather than “Takte”? Not four whole bars at the end of “the Adagio” (nearly impossible), but four beats, and slow ones (“adagio”), in a rallentando at the end of the whole aria?

A possible guess is that the composer wrote something like the following, and in light of Demmer’s difficulties, revised it in rehearsals, in time for the less demanding version to be copied into the Prague score:

For a vocally struggling tenor who was (according to the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung) “almost always singing flat,” this could be problematic enough. And if the speculation is correct, it would mean something important for the story: a further indication that Röckel was talking about the aria we know to have been in the 1805 score, and not (as Ries supposed) about an unknown version of the Adagio.

[5] Herr Röckel narrated the matter thus to me; he also assured me that he still possesses the vocal part in Beethoven’s own handwriting. So erzählte mir Herr Röckel die Sache, der auch die Singpartie in Beethovens eigener Handschrift noch zu besitzen versicherte.

Of course, the question we would most like answered is: what became of that manuscript? It is perfectly likely that Röckel had such a thing – if not entirely in Beethoven’s hand, then most probably a role-book on which the composer had marked the changes transforming the 1805 version to that of 1806, perhaps with an Einlage for the new Adagio. Singers in those days learned their roles from a copyist’s short-score, usually just two staves giving the vocal part, instrumental bass, and verbal or musical entrance cues. Theaters kept careful track of these books; if Leonore had not been abandoned from the repertory, the tenor would probably have been compelled to return his, if that is indeed what he had.

Much more music fits on a single page in that format, so it is far less likely that any whole sheets would have been torn out as they were from “Autograph 5” and the Prague score. It is less likely still, given what we know about those and about theater practice generally, that a complete new role-book would have been written out afresh for Röckel: copyist’s hours were a resource to be conserved where possible.

In other words, it is not just plausible but probable that Röckel could have seen, albeit under cancellation marks, the whole of the 1805 aria – and his reported remarks make far better sense if we assume that he had. If, for the sake of argument, we try interpreting the various errors as “probable misinterpretation by Ries of correct information from Röckel,” we may find ourselves knowing more about the aria’s history than was previously thought.

Here are four clues, paraphrased from Röckel/Ries so as to allow “wiggle room” for things that might have been misunderstood in the original interview.

• There was reason for Röckel to think that the aria had a one-movement form (Adagio in a-flat) at some point before his own performances.

• There was some question of a tenor not wanting to perform such a foreshortened scene and insisting on an “Allegro in f major.”

• There were vocal troubles, involving (though probably not limited to) a long-held F “at the end.”

• Something that modulated back to “F Major or (and?) f minor” was “left out” (ist...weggeblieben).

To these we can add a resumé of Beethoven’s further work on the idea of a one-movement aria. We have already seen that he produced a shortened and revised score of the Adagio. Someone, probably Beethoven’s friend Stephan von Breuning, produced eight additional lines of text, printed in the 1806 libretto. They seem calculated to fit the music of the Adagio, and the revisionmemorandum mentioned above contains an otherwise cryptic isolated word, “twice” (zweimal). It looks as though Beethoven was planning to have the Adagio repeated as a two-strophe romance, while slenderizing the piece so that it would bear repetition. The verses were sent to the printer, but no known musical source reflects the plan. Meanwhile, he sketched a new postlude leading directly from the Adagio to the entrance of Rocco and Leonore, thus omitting any second movement – but again there is no evidence that he produced a finished score of such an adaptation. Nor is there any score reflecting the abbreviations and key-changes signaled in the memorandum for the prelude and recitative. Apparently, something persuaded Beethoven to drop the ideas he was working on.

Here is what I think happened – the known facts interwoven with speculation based on the above:

• Beethoven completed the aria according to the plan laid out in the sketches: Adagio in A-flat, second movement beginning in F Major (“Flötenarie”) and continuing in f minor (“un poco agitato”).

• Demmer had trouble with it, particularly “am Ende,” to the degree that a blemish on the opera’s chance of success was foreseen.

• Beethoven – perhaps after first trying to ameliorate some of the difficulties – decided, or at least threatened, to cut his losses by omitting the aria’s second movement.

• The offended Demmer said he “did not want to perform” if his solo scene was to be so insultingly reduced.

• Whether this reduction was imposed before the premiere or only after is impossible to say, but the characterization of “the first version” as ending with the Adagio suggests that Röckel thought it was done before the opera was offered to the public.

• Such was in any case the plan for Demmer if he had remained in the cast; Beethoven set to work on a thoughtful re-conception of the scene, with a single-movement (but perhaps repeated?) Adagio aria, in anticipation of the 1806 revival.

• With Röckel’s arrival to replace Demmer, these efforts became unnecessary; the ideas set out in the memorandum were abandoned un-realized, and the composer felt able to restore the original plan of a two-tempo aria.

• However – consistently with the general imperative to shorten the opera – he did so using only the f minor portion of the second movement, and retaining the abbreviated version of the Adagio that he had already prepared.

• The “Flötenarie” was thus abandoned – but Röckel knew of its existence, whether from the copy he mentioned or from the accounts of his fellow cast-members, who had all been in the 1805 production. He also knew of the single-movement plan, whether because Beethoven described it to him or because Demmer had actually performed without “the Allegro.”

• Röckel spoke to Ries of both versions, but the latter misunderstood a crucial point. Having surmised that “the first version” meant “Beethoven’s original conception” and not “what was performed the first time around,” Ries interpreted everything else the tenor told him about the 1805 aria (the return to the tonic, the problematic vocal F “am Ende,” the decision to make a cut) as though all of that should have happened within some lost version of the Adagio.

• The same error could explain the only remaining puzzle: the supposition that “a tenor” had induced Beethoven to compose the “Allegro” in the first place. My guess: either Röckel had jumped to the situation of 1814 and Ries failed to make this clear, or the latter made another assumption to make sense of what he thought he knew. The “original version” was supposed to be Adagio only, yet “a tenor” was refusing to sing unless he got his “Allegro”...it takes only a small further step to call up the standard image from so many opera tales, the vain singer dictating to the composer according to the prerogatives of his rank.

These are of course hypotheses, not settled facts. A starting point for testing them would be a close re-examination of all accounts of the 1805 performances, to see whether any previously unimportant-seeming comment might be read differently in their light. It is also worth noting that thirteen volumes of Röckel’s handwritten diaries survive in a Düsseldorf museum library; the years covered are too late for Fidelio/Leonore, but as far as I am aware they have not been fully studied to see whether he might have written about his contacts with Ries or other Beethoven biographers. At the least, it seems possible that an important late testimony by two men close to Beethoven deserves a better reputation than it has had so far, and that it may even now shed some new light on a fascinating episode.

In the meantime, if the speculation is correct that poor Demmer lost his allegro before opening night, it would mean that the sketches reanimated here are being heard in public not for the first time since 1805, but for the first time ever.

V - Preparing an arrangement

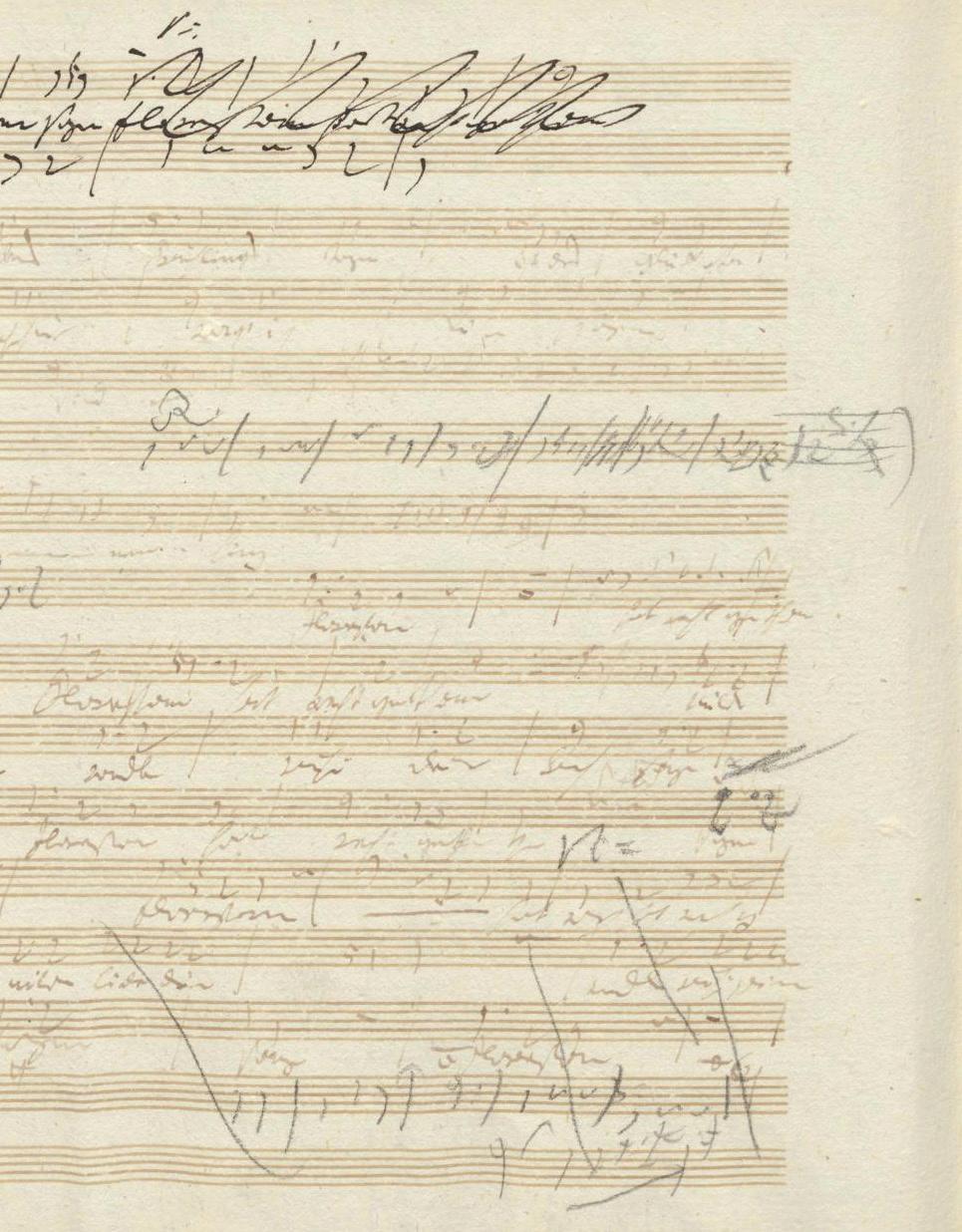

Everyone who has spent time with Beethoven’s sketches knows the impossibility of reading them, in any ordinary sense of the word “reading.” They are fragmentary and disjointed. Verbal cues are few and cryptic. The composer rarely recorded any decisions among multiple alternatives. He was not at all careful about aiming his pencil precisely among the lines and spaces of the musical staff. Clefs are left to be guessed, even if they change in mid-phrase. Clearly, he assumed that he could look back and remember what he had meant, but when someone else looks, there are puzzles in every line. One is forced to seek a mental conception of the thing being sketched before one can decide what notes are meant by the hasty scrawls – which may then, a few bars later, contradict the conception and send the reader back to start over.

Above all: the sketches almost never lead to a “nearly-finished” destination. Notwithstanding the thousands of sketched themes and phrases, the most significant part of Beethoven’s process took place in his mind, with the sketches serving as reminders rather than drafts of a full score. So, when Opera Lafayette invited me to attempt such a score, my answer could only be that I would study the sketches closely, and if they suggested something to my imagination, I would try. Beethoven sketched mostly “upper voice” thematic ideas, while the elements that make his music sound like itself are hardly centered upon the upper voice. There would be little point in mechanically composing a bass and filling in harmonies if one could not sense at least a possible Beethovenian character latent within the melodic lines.

The first task was to get familiar with all the sketches. Not for the purpose of determining which bits Beethoven “probably” used – that does sometimes become clear, but in the end he might have used any, or come up with entirely new ones. The real search is for whatever can help an arranger imagine something: for ideas that suggest other ideas, harmonies, orchestral patterns, dramatic shapes, points of reference.

As it turned out, the melodies do contain enough hints to encourage an attempt. In some of the sketches for the “Flötenarie” there are thematic fragments that recall the Adagio, and others that are “answered” in the surviving f minor passage. These similarities gave starting points for the choice of harmonies, accompanimental textures, and figuration. There is a chromatic moment in the vocal line that resembles one in the instrumental part of the 1814 score and lends itself to being harmonized the same way. There is one burst of vocal coloratura – but just one, which suggests it might have been a stopping point, an internal “cadenza,” with melody and motion resuming afterwards. (Another sketch shows a fermata – though without the vocal elaboration – at this point.) This gave something to go on for the rhythmic structure.

Perhaps best of all, there is a line in the flute part (occurring twice, and sketched many times in slightly different ways) that practically jumped off the page as being a recollection of Tamino’s “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” from Die Zauberflöte:

Mozart was of prime importance for Beethoven, and never far from his mind as he confronted the opera stage for the first time. Leonore’s big aria is a kind of “reply” to Fiordiligi’s – same key, emphasis on the same aspects of vocal virtuosity, and many musical resemblances even down to the concertante horn parts – but where Fiordiligi confesses an unfaithful heart, Leonore affirms fidelity at the risk of life itself. (Beethoven loved the music of Così but found the story distressing.)

There is a similar connection here, linked and contrasted at once. Sonnleithner’s libretto for Beethoven, just as the text of the “Flötenarie” begins, has the stage direction “Er zieht ein Bildnis aus dem Busen” (he draws a portrait from his breast). Tamino’s line in the “Bildnisarie,” just where the musical resemblance occurs, is “O wenn ich sie nur finden könnte” (Oh, if only I could find her!). Both tenors are gazing rapturously at a portrait – Tamino’s of an enchanting maiden he has never seen; Florestan’s of a beloved wife he is sure he will never see again. That poignant association told me immediately where to look (that is, straight to Mozart) for the dynamics and accompaniment. It also suggests a kind of jubilation in Florestan’s memories – not just sadness over his loss – and that in turn influences the way one might compose around the rest of the fragments.

The Adagio is more difficult, partly because the sketches are so numerous, partly because so many details and gestures appear, disappear, and then return in the composer’s long journey through this passage. (As late as the 1814 aria Beethoven went back to some sketched choices that he may have rejected already in 1805). There are hints in the quotations from this aria found in three of the four overtures, and the one played at the premiere (now called “Leonore no. 2”) at least gives concrete proof that certain ideas had been developed by that time even if they are not found in the sketches.

Two more clear facts can serve as anchors in the Adagio. One is that we have the composer’s definitive choices for the first two bars (in the “Autograph 5” mentioned above) and can thus gravitate to the possibilities most consistent with them. The other: in that much-discussed memorandum for revisions between 1805 and 1806, Beethoven wrote “ce moll statt es moll” (c minor instead of e-flat minor) by a sketch for the fourth line of text, “und die Ketten sind mein Lohn.” He did not put that plan into action; the cadence is in E-flat Major in 1806 and C-flat Major in 1814, and the sketches show him experimenting with c minor, f minor, and b-flat minor for a spot that obviously cost him great effort to decide. However, his annotation establishes that e-flat minor had been the choice in 1805, which guides an arranger to prefer the sketches containing such a cadence.

Finally, there is the fact that the 1806 aria required a new full score. It is the shortest of all versions we have (21 bars, as against 30 in 1814 and 36 in the last continuous sketchbook draft). But simple cuts and touch-ups could be written onto existing copies, as we have seen; the presence of the fresh copy suggests substantial rewriting. Indeed the 1806 Adagio contains several phrases entirely absent from all sketches, and these “new” ideas were kept in 1814. Some fifty years ago Willy Hess, editor of “Leonore” for the Beethoven critical edition, adopted the 1806 aria into the 1805 score and rather blithely suggested that its elements were probably in place already then. Both Tusa and Lühning find this unsatisfactory, and I agree: if so, then why the new copy? We can only guess, but my guess is that these themes were not present in 1805, and that our version should more or less ignore 1806 and follow the sketches instead. This choice also has the advantage of acquainting listeners with some striking dramatic gestures and a soaring final melody that Beethoven did not keep in the more restrained (but also very beautiful) 1806 version.

With these choices made, we have a near-complete draft of vocal and instrumental melody that is pure Beethoven. Our score is based mostly on what Tusa identifies as “continuity draft 5” for the Adagio and “continuity draft 3” for the “Flötenarie” – with the help of such fragments as we have of the finished music, and with recourse to other sketches when they offered more detail, or were more consistent with other clues, or simply yielded themselves more readily to my comprehension. What remained was to devise an accompaniment. It must be emphasized that this cannot be called a “reconstruction” of the aria; it is rather an attempt to compose around selected sketches. Though the result cannot possibly be half as good as the lost score, I hope it will serve to let Beethoven’s original conception of the piece, and some beautiful musical thoughts, speak at last after more than two centuries of silence.

VI - The score heard here

On the following pages is a “reading score” of the realization, laid out with one line for Florestan, two for woodwinds, and two for strings. To recapitulate in brief: the first dozen bars are nearly all Beethoven (first two from the actual 1805 copy in “Autograph 5”; next four from the quotation in the 1805 overture; then six more lifted from the overture or the completed versions of the aria, slightly adjusted to fit the chosen version of the vocal line from the sketches). After that, from bar 13, the guesswork starts. Although the entire vocal line comes from one or another of the sketches, the orchestral part is all invented, except for the following hints or fragments from the sketchbook:

• a written-out chord for the downbeat of bar 15 • the middle-register clash of E-flat and F-flat on the downbeat of bar 17 • the upper instrumental voices (including the A-natural) in bar 21 • a figured-bass notation for the chord used here in bar 35, found between early sketches for the Adagio and the “Flötenarie” • the topmost instrumental voice in bars 41-47 (downbeat) and 52-59 (downbeat); a different version of this, in another sketch, confirms that it is intended for flute • the return of the flute theme in bar 63 • the upper instrumental voice in bars 69-74 (once again a different sketch contains the assignment of this passage to clarinet), and the first off-beat in bar 71

Where this score breaks off, the known conclusion takes over (the Prague copy lets us restore the 1805 readings with only the most minimal speculation). As described above, the transcriptions of the sketches are not and cannot be exact. I read some of them differently from Tusa and Lühning, who also read them differently from one another; some guessing is inevitable. Various minor adjustments are necessary to make rhythms add up and barlines come out right. Sometimes – for instance when deciding whether one thinks Beethoven meant a flat or a natural, or whether he was aiming for a line or a space on the staff – there is no solution but to decide the harmony first and then interpret the sketch to fit.