24 minute read

The Musical Revolutions of Marie Antoinette

The Musical Revolutions of Marie Antoinette Julia Doe

Few repertories of Western art music have been more persistently identified with absolutist politics than the serious operas (tragédies lyriques) and courtly ballets of Louis XIV’s Versailles. The soundscape of the French Baroque was consolidated under the auspices of monarchy and functioned as an embodiment of governmental propaganda and prestige. Music historians have often traced a narrative of decline from this apex of French royal patronage. Over the course of an “enlightened” eighteenth century, the story goes, the Bourbon rulers became increasingly disinvested in the musical arts; composers instead catered to the demands of a Parisian public sphere (reflected, for example, in entrepreneurial new concert series divorced from Crown sponsorship). It is true that the kings that succeeded the Roi Soleil possessed neither his passion for music nor his savvy at exploiting its political potential. Louis XV was personally fond of opera, but far less active as a patron than either his wife, Marie Leszczyńska, or his maîtresse en tître, Madame de Pompadour. Louis XVI was rather more apathetic toward the art form—so much so, apparently, that it made the news when he managed to stay awake through an evening at the theater.

When Marie Antoinette arrived in France in 1770, government administrators feared that she might share her new husband’s aversion to music. As M. Elizabeth C. Bartlet has discussed, she reacted with seeming indifference to the spectacles presented for her wedding festivities—lavish revivals of “canonical” court tragedies by Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau. The Mémoires secrets expressed concern that the musical offerings had “bored her to tears” (18 May 1770). It quickly grew apparent, however, that these official anxieties were somewhat misguided: if the Habsburg archduchess was openly skeptical of la musique ancienne, the aging ceremonial repertory of the Bourbon kings, this was not because she did not like music. Rather, it was because her tastes were more modern, sophisticated, and cosmopolitan than those that then prevailed amongst the French royal family. In the years that followed, Marie Antoinette would emerge as a performer and patron of expansive politico-cultural vision. Indeed, her influence would revolutionize aesthetics and programming at Versailles—with repercussions that reverberated in Paris, in Francophile courts throughout Europe, and in the distant reaches of the French colonial empire. Opera Lafayette’s festival, “The Era of Marie Antoinette, rediscovered,” thus offers a corrective to several ingrained assumptions about music in the French Enlightenment—situating this repertory within a global context, and reframing gendered narratives centered on kingly patronage (Doe [1]; Bartlet [2]; Powers [3]).

Marie Antoinette as Performer and Patron

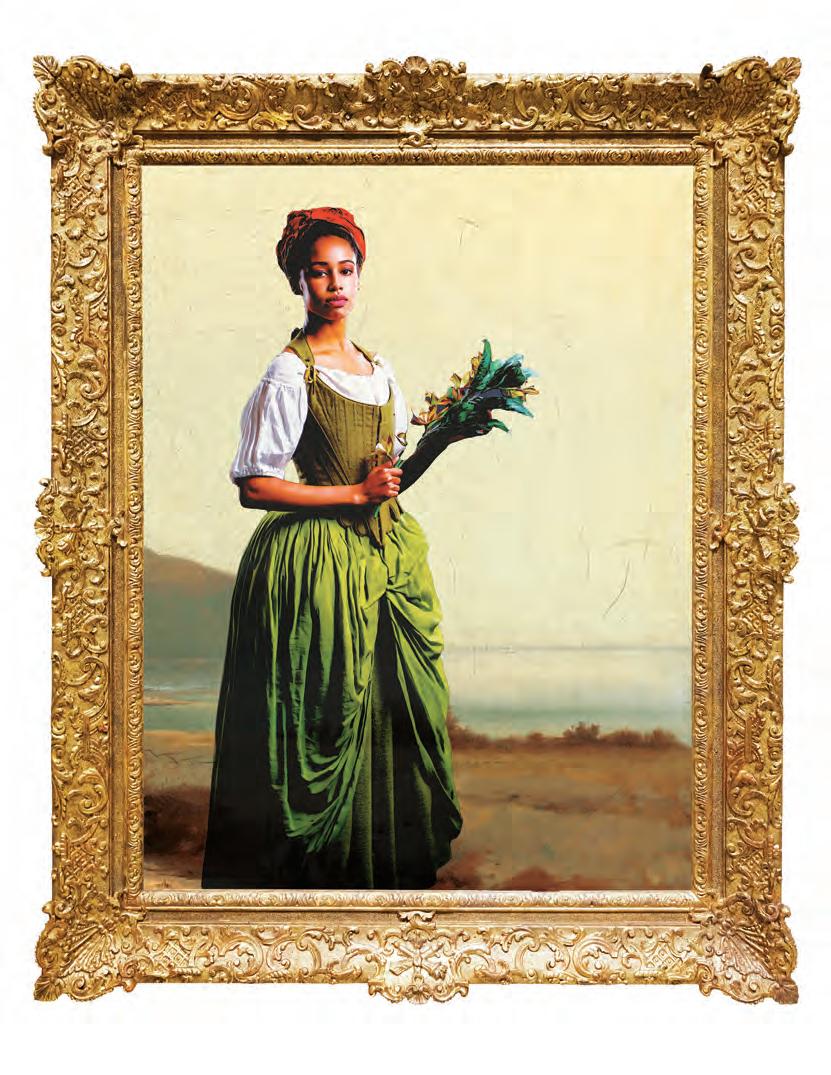

Marie Antoinette’s artistic predilections were shaped during her childhood in Habsburg Austria. In the 1750s and 1760s, under the aegis of the Empress Maria Theresa, Vienna was “Europe’s most fertile ground for innovation in music drama both sung and danced” as stated by Bruce Alan Brown. The programming of the Austrian court theaters showcased a number of important, cosmopolitan currents: serious and comic works Fig. 1. Franz Xaver Wagenschön, “Archduchess Maria Antonia at the Spinet,” 1770: A portrait of Marie Antoinette, dating from her teenage years. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. in Italian (opera seria and opera buffa), “reform” operas by Christoph Willibald Gluck (including the well-known Orfeo ed Euridice), and forward-looking, naturalist ballets (ballets d’actions) from the choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre. It is ironic that Marie Antoinette’s preferences were initially perceived as hostile to the aesthetic of Versailles, for her father, the Emperor Francis I, was born in Lorraine, and had enthusiastically supported French artists, architects, writers, and dramatists in the Austrian capital in the years around mid-century. French was the language of choice of the Viennese aristocracy, and a company of French comédiens was in regular residence at the royal palaces at Laxenburg and

Schönbrunn. The archduchess was trained in declamation and deportment by a pair of actors from Paris and took in several imported French dialogue operas (opéras comiques) and ballets. Her first documented musical performance—at the age of four—was not of an Italian aria or Viennese keyboard divertimento but of a French popular song (vaudeville), which she sang for the familial celebrations marking the name day of her father in October of 1759 (Brown [4]; Doe [5]).

Musical performance would be a lifelong Fig. 2. Collection of airs for voice and harp, 1783: This set of works was composed by Philippe-Joseph Hinner (Marie Antoinette’s harp tutor) and pleasure for Marie published by Naderman (her preferred harp manufacturer). Bibliothèque Antoinette, and a nationale de France, department of music, A-34381 (3). critical component of her politicized selffashioning. She was schooled in several instruments in her youth, favoring the keyboard and the harp (Fig.1). Alongside her siblings, she was also given instruction in figured bass and rudimentary composition, studying with the Habsburg courtaffiliated Gluck, Johann Adolph Hasse, and Georg Christoph Wagenseil. Marie Antoinette continued this musical education after her arrival in Versailles. Her letters suggest that she devoted an hour or more every afternoon to lessons and practice —a routine she would keep up, on and off, for the duration of her reign. (At one point, she even requested that her harp tutor, Philippe-Joseph Hinner, undertake his own course of advanced training in Italy, so that he would be able to teach her more effectively; (Fig.2.) Music-making was not simply a solitary activity, but a vital form of diversion amongst the members of Marie Antoinette’s elite social circle. As queen, she would sponsor small-scale concerts in her private apartments several times each week (or upward of one hundred times every year). The archives of the royal

Fig. 3. Atelier Ziesenis, Scene 9 from Les deux chasseurs et la laitière, watercolor and ink: This image depicts characters from an opéra comique by Duni, performed by the troupe des seigneurs at the Château du Petit Trianon. Marie Antoinette would have played the milkmaid, Perrette (pictured right). Bibliothèque nationale de France, Album Ziesenis, Fol-O-ICO-003.

household—which contain extensive documentation of Marie Antoinette’s music purchases—provide a clear window into her personal tastes. Notably, the queen favored genres then marked as “progressive” in style (particularly in comparison to the antiquated and eminently “French” repertory of la musique ancienne). Her library skewed largely toward arias and arrangements from the latest opera buffa and opéra comique. She ordered full scores of recent French lyric comedies on a quarterly basis, along with dozens of extracted numbers from this same corpus. She was also a regular subscriber to the Journal d’ariettes italiennes, a bi-monthly compendium of modern Italian composition, and would often request to have copies bound and given as gifts to her relatives and close friends (Heartz [6]; Arneth & Geffroy [7]).

Contrary to her reputation for frivolity in other domains, the evidence suggests that Marie Antoinette approached her musical endeavors with considerable earnestness. After the births of each of her children, for instance, she requested a stage be built in her apartments, so that operatic performances might continue unabated as she convalesced. The all-encompassing nature of this engagement is perhaps best demonstrated in the rehearsal and scheduling of the infamous troupe des seigneurs, the amateur (or “society”) company Marie Antoinette formed in the 1780s to mount

spoken and lyric comedies in her private theater at the Château du Petit Trianon. Among other roles, the queen portrayed the shepherdess, Jenny, in Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny’s Le roi et le fermier and the milkmaid, Perrette, in Egidio Duni’s Les deux chasseurs et la laitière (Fig.3). The society troupe prepared its performances extensively, with coaching from composers and actors of the royally affiliated stages, and up to five days of rehearsal before the presentation of each. The Count of MercyArgenteau (Marie Antoinette’s Austrian “minder,” who reported on her activities to Maria Theresa in Vienna) seems not to have been exaggerating when he remarked that musical theater had become the “single and unique” obsession of the monarch (Arneth & Geffroy [7]).

Opera Lafayette’s concert, “The Musical Salon of Marie Antoinette,” curated by the harpist Sandrine Chatron, provides a rare window into this soundscape of aristocratic leisure. The program foregrounds genres in vogue with eighteenth-century musical amateurs: small-scale instrumental sonatas, elegant popular songs (romances), and chamber arrangements of operatic arias. In addition, it casts a spotlight on artists with personal connections to the queen, including Hinner and Gluck, who served as her music tutors; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whom she met as a child in Vienna; and Jan Ladislav Dussek and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, instrumental virtuosos who accompanied her private soirées. Taken together, the body of composers and works on this program underscores the “internationalization” of the French court repertory in the late ancien régime. During Marie Antoinette’s reign, Versailles drew artistic talent from across Europe and the French Atlantic world. At the same time, the repertory favored at this courtly center circulated extensively in print, aided by new technologies of engraving and a concomitant expansion in the commerce of music for domestic use (Barbier [8]).

Ceremonial Music at Marie Antoinette’s Versailles

Marie Antoinette’s fondness for music was thus established during her childhood and reinforced through her extensive activities as an amateur performer. But from her very first months in France, these private preferences also influenced the public theatrical calendar at court—the ceremonial performances offered by France’s three Crown-supported companies (the Opéra, Comédie-Française, and Comédie-Italienne) at the palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau. After the disastrous reception of the royal wedding festivities in 1770, the balance of Bourbon entertainments was quickly altered; Louis XV was convinced to add more light comedies to the upcoming schedule for the sole reason that “it was suggested . . . that this would be agreeable to Madame la dauphine” (Arneth & Geffroy [6]).

After the accession of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette took an even more active role in shaping the operatic productions of the court. Given the lack of interest in such

matters from her husband, it was she who began to submit suggestions for repertory or to request that a planned program be adjusted to suit her current inclinations. The diaries of Denis-PierreJean Papillon de la Ferté, the intendant of court spectacles, are filled with complaints of the hardships he endured to ensure that these interests were fulfilled. (During one stretch of performances, for example, he was forced to rush to the capital and work overnight preparing costumes for a ballet abruptly added to the next day’s program at Versailles.) A few years into her reign, Marie Antoinette was firmly in charge of these entertainments. As Fig. 4. Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, “Christoph Willibald Gluck,” 1775: The famed operatic composer served as childhood music tutor to Marie Antoinette. Her support would assure his the intendant wrote matter-of- subsequent success on Parisian stages. Kunsthistorisches Museum, factly before the opening of the Vienna. autumn Fontainebleau season in 1777: “The trip to Fontainebleau will take place. The queen chose the spectacles as she desired” (Papillon de la Ferté [9]). An analysis of the operas staged at the court theaters during this period reveals a broad evolution in this repertory—and a striking tendency towards contemporary composition. As we have noted, theatrical programming at Versailles prior to Marie Antoinette’s tenure was dominated by the venerable tragédies lyriques of Lully, long associated with the golden age of Louis XIV. The musicologist Richard Taruskin describes these works, accordingly, as the “courtiest court operas” ever written. The 1770 wedding revival of Lully’s Persée seems to have made a strong impression on Marie Antoinette, though precisely the opposite impression that officials had intended: she would witness only one further court production of the composer’s output in the two decades that followed. Rameau fared little better, with a single fullscale performance after 1770: a presentation of Castor et Pollux to mark a visit from the queen’s brother, Emperor Joseph II, in 1777. Such time-honored examples of la musique ancienne were replaced with updated tragedies by the younger generation of foreign composers favored by the queen. Gluck followed his former pupil to France

in 1773 (Fig.4). Several of the composer’s French-language operas were given at court, and he would remain closely linked to Marie Antoinette throughout these residencies abroad. As the Mémoires secrets reported, the queen had granted the Austrian musician the right of entry “chez elle at any hour” (14 January 1774). Marie Antoinette’s well-publicized support for Gluck would not prevent her patronizing a number of Italian composers set against him as rivals in the periodical press. Niccolò Piccinni was brought under her protection by 1776 and enjoyed several prominent court premieres (Phaon and Pénélope); Antonio Salieri and Antonio Sacchini would enjoy similar privileges in the 1780s (Taruskin [10]).

Even more dramatic than these changes in the courtly repertory of lyric tragedy was a shift in the overall distribution of musical genres in favor at the royal residences. Indeed, for all the legitimate scholarly attention surrounding Marie Antoinette’s impact on serious opera, Gluck does not even make the list of the top-ten most frequently staged composers during her time in Versailles. The most successful court artists of the 1770s and 1780s were instead established stars of opéra comique, led by the queen’s personal director of music, André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry, and followed by Monsigny, Duni and François-André-Danican Philidor. Opéra comique had enjoyed a rapid rise in status in the years since mid-century, so its inclusion within these theatrical seasons was not entirely unprecedented. But it should be emphasized that critics considered the genre to be subsidiary to tragédie lyrique (and therefore unusual within the court context) for several reasons. Although opéra comique was now performed by the Crown-sponsored Comédie-Italienne, the genre had popular roots, originating at the fairground theaters of the French capital. What is more, dialogue operas frequently featured lower-class characters and an accessible musical language that contrasted sharply with the mythological settings and elevated idiom of the conventionally “absolutist” musique ancienne. Given these distinct historical and musico-dramatic characteristics of the comic genre, its predominance within the court repertory (and the extreme rapidity at which it attained this predominance) should be read as a significant disruption to the theatrical status quo.

The centerpiece of Opera Lafayette’s festival, a fully staged production of Grétry’s Silvain, embodies the forward-looking operatic aesthetic of Marie Antoinette’s Versailles. The work is a parable of “enlightened” thought, its plot pairing a lesson in domestic reconciliation with an attack on aristocratic privilege. (The title character has been estranged from his noble relatives and living in the countryside after his “unsuitable” marriage; his benevolent father ultimately intervenes, having been convinced by the peasants’ example that “simple virtue held more weight than birth.”) While this progressive message might seem out of place at the very center of French absolutism, it was meant to project (whether ingenuously or not) the modernizing outlook of the regime, as well as the queen’s openness to the fashionable ideals of the

philosophes. And, indeed, Grétry’s opéra comique would prove immensely successful at the Bourbon court theaters, presented more than a dozen times at Versailles and Fontainebleau between its 1770 premiere and the onset of the Revolution. Notably, the work—and the genre of opéra comique, more generally—would also come to define the sound of French music outside of metropolitan France. Silvain was disseminated widely, with documented productions throughout Europe (Amsterdam, Brussels, Frankfurt, Vienna, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, and Copenhagen, to name just a few) and the French Atlantic (including Cap Français, Port-au-Prince, and New Orleans). Comic operas like Silvain were readily “exportable”—modest in scale and economically efficient to reproduce. Because they were structured with spoken dialogue rather than recitative, their texts were also relatively straightforward to translate; before the end of the century, Silvain would be reworked into Danish, Dutch, German, Russian, and Swedish. The theatrical repertory associated with Marie Antoinette would thus promulgate her “enlightened” values on a vast European stage. It would simultaneously, however, expose the hypocrisies of these values in the profoundly inegalitarian context of the French colonial empire, as Laurent Dubois and Kaiama L. Glover so eloquently describe in their accompanying essay in this booklet, Theater and the Worlds of Saint-Domingue (Loewenberg [11]; Clay [12]).

Marie Antoinette and the Parisian Marketplace

The Crown-affiliated dramatic institutions of the ancien régime held a dual identity. While the royal actors were responsible for the entertainments of the Bourbon court, they were primarily based in the capital, and granted a relative degree of autonomy for the internal governance and repertory decisions of their Parisian theaters. Much more than her Bourbon predecessors, however, Marie Antoinette expressed an interest in these companies’ inner workings and a willingness to intervene in their public offerings. Government officials often discussed placing theatrical regulations “before the eyes of the queen” prior to approval; these ministers also received performance schedules from the Crown-subsidized troupes in advance, so that Marie Antoinette could plan her trips to the capital around these events. As Patrick Barbier has noted, visits by members of the royal family to the Parisian theaters were rare in the years before 1770—largely reserved for “official” political and ceremonial occasions. Marie Antoinette, by contrast, was a frequent and prominent presence at these spectacles. She maintained annual box subscriptions to each of the Opéra, Comédie-Française, and Comédie-Italienne, and made at least 120 appearances at their Parisian productions between 1773 and 1787. As queen, it is worth underscoring, she held the power to shape these performances to her liking. There are memoranda in the archives of the royal household for couriers sent from Versailles to Paris to alter, on short notice, the advertised schedules of the royal troupes to accommodate the monarch’s wishes. On one evening in 1777, for example, Marie

Fig. 5. Payment record from the French royal household (menus plaisirs): Memorandum detailing payment for porters alerting the Parisian Comédie-Italienne that “the queen has requested Silvain in place of La servante maîtresse.” Archives Nationales (Paris), O1 3050.126 (1777).

Antoinette instructed the Comédie-Italienne to substitute her preferred Silvain for the planned program of La servante maîtresse, a French translation of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s La serva padrona (Fig.5). The queen might even exert agency over casting: while “B” casts (doubles) tended to perform on Sundays, the star players would be asked to rush from home to the theater (essentially donning their costumes en route) if Marie Antoinette sent word of her intended attendance (Barbier [8]).

The queen’s support for individual composers and musical works might assure their success on Parisian stages. Her enthusiastic response was said to have sparked the favorable reception of Gluck’s first tragédie lyrique for the Paris Opéra, Iphigénie en Aulide, in 1774—paving the way for a “revolution” in the repertory of this institution in the years that followed. The Gluckian reform at the Opéra was both pragmatic (heightening the performance standards of the company’s singers and dancers) and aesthetic (imbuing the tragic genre with a renewed psychological complexity, harmonic sobriety, and sense of integrated dramatic planning). By the end of the ancien régime, Gluck’s oeuvre was essential to the output of this lyric theater. As various internal memoranda related, audience taste at this institution was now “entirely determined by the works of M. Gluck”—to the extent that the revival of an older tragedy virtually guaranteed “the complete loss of expenditures” as recorded in the menus plaisirs. Marie Antoinette’s attentions similarly raised the profile of artists in her favored domain of opéra comique. One critic reported that, “because the light and agreeable music” of this genre greatly pleased the queen, “its authors increasingly triumphed over their rivals, and gained an increasingly prominent reputation amongst the elite society” of the French capital (Mémoires secrets, 15 July 1770) (menus plaisirs, Archives Nationales [13]).

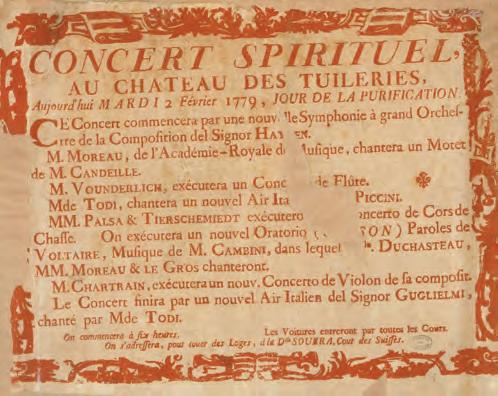

If Paris was a major European center of operatic composition in the eighteenth century, it was also a locus of innovation in sacred and in instrumental music—as programmed, notably, in new concert series like the Concerts de la Loge Olympique (the venue that commissioned the famous “Paris” symphonies of Franz Joseph

Haydn, as well as many dazzling violin showpieces of Saint-Georges) and the Concert Spirituel (the most prestigious concert organization of the age, running between 1725 and 1790; (Fig.6). As its moniker implies, the programming of the latter institution was originally focused on spiritual repertory, but Fig. 6. Poster for the Concert Spirituel at the Tuileries Palace, 2 February subsequently evolved 1779: Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra, Affiches-Réserve 29 (1779, 02–02). to include a rich variety of genres: symphonies, concertos, and operatic extracts, alongside sacred works. These Parisian concerts have often been taken to demonstrate the “democratization” of musical patronage and consumption in the late ancien régime—run by individual entrepreneurs (rather than royal sponsors), relatively affordably priced, and with dynamic and eclectic programming meant to appeal to broad audiences. As Peter Schleuning has argued, the public concert functioned as a site of “bourgeois musical struggle” in which the rising middle classes “tore down the barriers and fences which had reserved cultural goods for the feudal elite”. But here, again, Marie Antoinette retained an influence: appearing with some regularity at performances, sponsoring notable virtuosos, and developing enduring associations with certain works (such as Haydn’s Symphony No. 85 in B-flat major, nicknamed “La Reine” after the queen’s preference for it) (Blanning [14]). Opera Lafayette’s program, Concert Spirituel aux Caraïbes highlights the wideranging impact of these new forms of concert culture—as well as their encapsulation both of the hopeful possibilities and the stark limitations of the “enlightened” eighteenth century, in musical terms. The commercial model of the Concert Spirituel sparked numerous imitators throughout Europe, expanding public access to art and music in Leipzig, Stockholm, Berlin, Saint-Petersburg, Bordeaux, and Vienna, among other cities. The series proved so portable, indeed, that it was also replicated throughout the French colonial Caribbean. The transatlantic movement of French musicians and impresarios underscores the entanglements, financial and artistic, between colonies and metropole in the late ancien régime. The expanding markets for new music were interpreted within France as an embodiment of a progressive,

non-hierarchical public sphere. And yet, as Pedro Memelsdorff and Andrei Pesic have recently argued, they both reflected and were facilitated by a broader economic system based upon imperial exploitation (Pesic [15]).

The politicized reception of Marie Antoinette’s artistic projects was—and continues to be—fraught with paradoxes, with ramifications for both the personal reputation of the queen and contemporary understandings of the French musical Enlightenment. On one level, somewhat counterintuitively, there was a stark disjuncture in eighteenth-century criticism between appraisals of forward-looking musical developments, writ large, and appraisals of the queen’s role in sponsoring them. The multifaceted strands of musical “revolution” taking hold in the 1770s and 1780s—the pan-European reforms of Gluck and Piccinni, the rising profile of lyric comedy, the “democratization” of instrumental concert music – were largely embraced by French audiences and commentators. The queen’s patronage of these developments, however, was not uncontroversial, emerging as a prominent strand of censure in the press. Marie Antoinette’s private performances of opéra comique, for example, were held up as evidence of her impropriety and ignorance of royal decorum, resented by courtiers accustomed to deriving social capital through open access to the monarch. Her support for elaborate programs of ceremonial spectacle at Versailles and Fontainebleau fared little better—eliciting scrutiny for their frivolous expense. As Papillon de la Ferté grumbled in 1778: “Since the 12th of October, there have been fourteen days of performances, at Marly, at Versailles, and in the queen’s quarters—comedies, operas, buffa works, ballets. This does nothing to reduce our expenses, either in the productions themselves or in the little theaters that had to be erected for the occasion … None of this pleases the minister of Finance, and it amuses me even less, for the public likes nothing more than to enormously exaggerate this sort of expenditure” (Papillon de la Ferté [9]).

Finally, the queen’s association with composers born outside of France intersected with broader concerns about her foreign allegiances – the lingering suspicion that, despite her marriage, she remained more Habsburg than Bourbon. Marie Antoinette was accused of acting in both the political and musical interests of her mother and brother; the queen’s support for the Austrian Gluck (as well as the Italians Piccinni, Salieri, and Sacchini) over the established representatives of la musique ancienne provided fodder to those skeptics who deemed her insufficiently French. These pressures reached their peak at the final Fontainebleau season of Marie Antoinette’s reign, in 1786; an opera championed by the queen—Sacchini’s Oedipe à Colone— was hastily replaced by the work of a French composer (Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne’s Phèdre), in response to criticisms in the Gazette musicale de Paris, that she accorded “too much favor to foreigners”. In the politically charged atmosphere of the late

ancien régime, artistic choices had far-reaching consequences—ones that would be detrimental for Marie Antoinette’s reputation even as they proved “revolutionary” for French musical culture as a whole (Doe [1]; Geoffroy-Schwinden [16]).

More broadly, the works sponsored by the queen—and their contested reception history—prompt us to reconsider the mechanisms through which this repertory generated political meaning. Put another way, the music featured in Opera Lafayette’s festival informs us about ancien-régime politics by demonstrating (and powerfully so) that meaning was not simply present “within” the works themselves, but produced through the complex interaction of authorial intent, audience composition, and venue of performance. The body of pastoral opéras comiques patronized by Marie Antoinette offers a case in point here. As we have noted, French lyric comedy of the late eighteenth century has often been associated with the progressive worldview of the philosophes, for the manner it foregrounded the musical idioms and social concerns of the third estate. Presented in a Parisian or ceremonial courtly context, an opera like Silvain might be used to broadcast the “open-mindedness” of the regime, or the monarchy’s ostensible concern for its rural dependents. Produced at the queen’s faux-rustic retreat at the Petit Trianon, pastoral opera had starkly different implications. Marie Antoinette’s staged recreations of country life were interpreted less as a sign of engagement than of detachment, a troubling displacement of realworld responsibilities into the illusory realm of the theater. This chasm grew more acute in France’s Caribbean colonies, as Callum Blackmore details in his program note for Silvain; here, the pastoral utopianism of Silvain could be used to justify the perpetuation of a plantation economy based upon enslavement. The opera acquired yet further layers of meaning in Louisiana at the turn of the nineteenth century, its critiques of land rights now set against a backdrop of American territorial expansion. Opera Lafayette’s festival encourages us to be attuned to this historical nuance: to the circuitous global paths that artists traveled, and to the manner their performances re-sounded distinctively as they did so.

Bibliography

1. Doe, Julia. The Comedians of the King: Opéra Comique and the Bourbon Monarchy on the Eve of Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

2. Bartlet, M. Elizabeth C. “Grétry, Marie-Antoinette and La rosière de Salency.” Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 111 (1984–1985): 92–120.

3. Powers, David M. From Plantation to Paradise?: Cultural Politics and Musical Theatre in French Slave Colonies, 1764-1789. Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2014.

4. Brown, Bruce Alan. Gluck and the French Theatre in Vienna. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

5. Doe, Julia. “Marie-Antoinette, la musique et la danse.” In Histoire de l’opéra français du roi soleil à la Révolution, edited by Hervé Lacombe, pp. 577–585. Paris: Éditions Fayard, 2021.

6. Heartz, Daniel. “A Keyboard Concerto by Marie Antoinette?” In Essays in Musicology: A Tribute to Alvin Johnson, edited by Lewis Lockwood and Edward Roesner, 201–212. Philadelphia: American Musicological Society, 1990.

7. Arneth, Alfred von and M. A. Geffroy, eds. Correspondance secrète entre Marie Thérèse et le Cte de Mercy-Argenteau. 3 vols. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Cie, 1874.

8. Barbier, Patrick. Marie-Antoinette et la musique. Paris: Grasset, 2022.

9. Papillon de la Ferté, Denis-Pierre Jean. Journal de Papillon de la Ferté, intendant et contrôleur de l’argenterie, menus-plaisirs, et affaires de la chambre du roi (1756–1780). Edited by Ernest Boysse. Paris: Ollendorf, 1887.

10. Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Vol. 2 of The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

continued

11. Loewenberg, Alfred. Annals of Opera, 1597–1940. 3rd ed. London: John Calder, 1978.

12. Clay, Lauren. Stagestruck: The Business of Theater in Eighteenth-Century France and its Colonies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013.

13. Records of the menus plaisirs, Archives Nationales (F-Pan), Série O1 616–618, 842, 848–853, 2809–2810, 3026–3086.

14. Blanning, T. C. W. The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

15. Pesic, Andrei. “The Flighty Coquette Sings on Easter Sunday: Music and Religion in Saint-Domingue, 1765–1789.” French Historical Studies 42 (2019): 563–593.

16. Geoffroy-Schwinden, Rebecca Dowd. “A Lady-in-Waiting’s Account of Marie Antoinette’s Musical Politics: Women, Music, and the French Revolution.” Women & Music 21 (2017): 72–100.