3 minute read

Candid Camera: Using Visual Data as a New Way to Weigh Cattle

By Vanessa Rotondo and Dr. Katie Wood, Department of Animal Biosciences, University of Guelph

There is an old saying in Hollywood: “the camera adds 10 pounds.” Although that may not be literally true, camera systems can in fact be used to predict body weight. A new research project at the University of Guelph has been developing the use of visual spectrum data from camera systems to automatically and accurately estimate body weight and growth in calves.

Having accurate body weights on animals can be an important management tool for producers. Beyond benchmarking animal performance, animal weight can give insight into estimating nutrient requirements, be used as a health indicator, serve as a tool for genetic selection, and more. However, many farms either do not have access to scales and weighing infrastructure or do not have the time nor labour to regularly weigh their cattle. According to the 2016 Ontario Cow-Calf Survey, only 44 per cent of survey respondents owned a scale. This is where the base of this research starts. Is there another way to capture animal weights without the need for weighing infrastructure and labour associated with weighing cattle?

The project brought together Dr. Medhat Moussa and research staff David Weales from the School of Engineering, Dr. Katie Wood and graduate student Vanessa Rotondo from the Department of Animal Biosciences, and OMAFRA industry experts to develop a system that passively collects calf images to see if the images can be used to automatically identify key body points, which could be used to predict body weight.

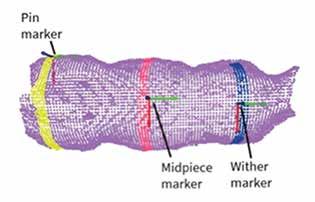

Although heart girth circumference has long been correlated with body weight and is the basis behind animal weigh tapes that many producers still use, there may be other measurements that improve the accuracy of body weight prediction. To investigate the relevance of these other measurements, over 100 calves from the Ontario Beef Research Centre were weighed and 19 different body traits were measured weekly from two to eight weeks of age. Once measurements were collected, algorithms were generated to predict calf body weight. Measurements including heart girth, width over the pin bones, and width across the eyes, combined with other traits, were found to be able to predict calf weight with high accuracy.

Measuring over 19 body dimensions traits on young calves at the Ontario Beef Research Centre Measurements

Calf standing under the prototype camera system used to passively capture visual data which can be used to estimate body weight

Now that we can conclude that the body measurements studied can accurately assess body weight, the question still remains, “how can we weigh calves and collect all this ‘big data’ in a timely manner?” This is where the engineering begins. After the calves were measured, they were led with a halter to a prototype image capture system. The cameras were mounted on either side of a wooden frame and images from both sides of the calf were captured as the calf stood under the frame. From the images, thousands of data points were generated to develop a digital model of the calf. From here, computer algorithms were applied to isolate the calf from the background environment and to automatically identify these key body features important in predicting body weight.

This project uses concepts from the “digital agriculture” revolution, where large amounts of data is collected and analysed in order to provide producers with decision-making tools to improve efficiency and production. Although perhaps more abundant in other agricultural sectors, “big data” can have applications in the beef industry too. Applications like the visualized body weights can passively generate data, which will enable producers to make informed management decisions and allow for early intervention based on actual information gathered. This may allow for early detection of health concerns, prediction of growth curves and more accurate information on individual animals. These camera-based systems have some advantages over traditional scales, as the infrastructure costs are much lower and systems can be installed within the pen. This eliminates the need to move animals, allowing for data to be captured from each individual animal on a daily basis, yet minimizing labour costs for producers.

So what’s next? The research team hopes to adapt this technology to run completely autonomously by installing the system in a creep pen or mounting it over a water bowl or feeder while incorporating a RFID tag reader to automatically identify animals. In the future, the research team also hopes to validate this technology for older cattle of both beef and dairy breeds.

Although the camera may not actually add 10 pounds, using visual data to make better informed animal management decisions may help producers get their cattle to gain those ten pounds faster. OB