7 minute read

ARTIST

from OTK Issue 03

by One To Know

Democratizing Art

By Jocelyn Tatum

Advertisement

SARAH AYALA walked into the interview wearing a black-and-white houndstooth suit with her long blonde hair draped over her shoulders. She had an antique gold chain with a Jesus charm resting on the sternum of her pale skin. It stood out. Her tattoos along her forearms beckon to her love of Eastern philosophies, her heritage and best friends who share matching tattoos. You may be wondering why any of this is relevant, but it is. These details all tell part of her story as an artist, a teacher, a white-presenting Hispanic, a history-loving philosopher and a descendant of Mexican goldsmiths.

Sarah doesn’t always dress that nice in a museum. If she is meeting people for work, then she may, like the day we met at the Amon Carter by the gift shop. On a regular day she dresses down, making the fine arts sanctuary less untouchable. Sarah’s mission is to bring art outside the ivory walls of museums and into the community — the democratization and decolonization of the fine arts. “I try to strike a balance between doing that, because I feel like if I dress up too much, other people will see the museum as inaccessible,” she says.

Afterall, Sarah was a dancer, and it was this element of the fine arts that pulled her out of a dark period in high school when she thought one bad choice at 17 had ruined her whole life. She would soon attend TCU, join a sorority, and major in education to work with kindergarteners. Then there was a moment in college when Sarah realized her teaching degree at TCU may not be her path. “Maybe I don’t teach it, maybe I do it instead,” she says.

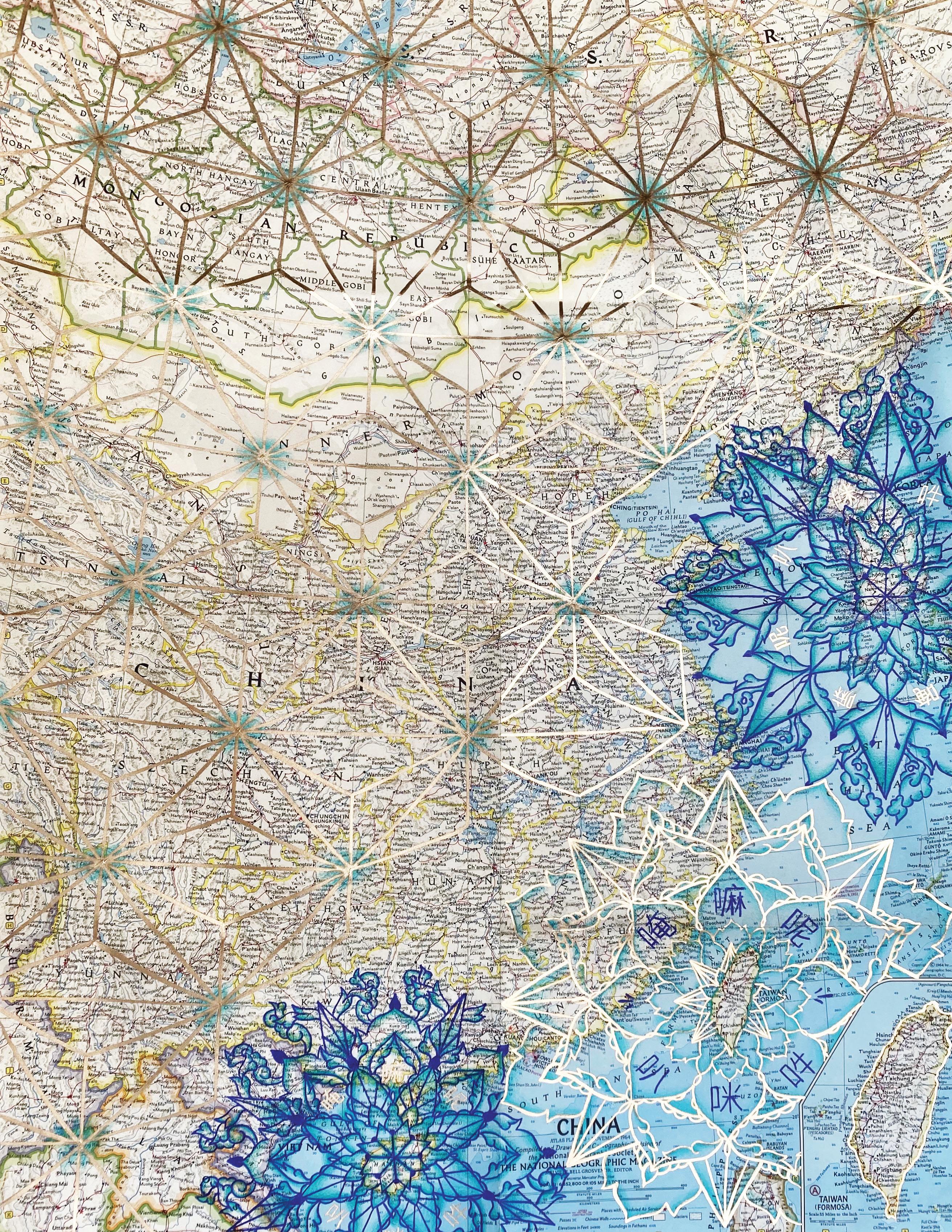

When Sarah started out as an artist, she was creating work live back when Leon Bridges was a local sensation playing Mondays at Lola’s Trailer Park on West Fifth Street. But at some point, she couldn’t see her vocation as an artist much past just making pretty things. Up until then, most of her art had been inspired by Eastern philosophy and mythology where she created pretty meditative patterns like mandalas. This all started when she read The Tao of Pooh on a road trip across the American Southwest in college.

Left: Amon Carter Museum of American Art Carter Community Artist announcement. Photo by Paul Leicht Right: Pencil and gold leaf on 1964 map, 18x26”. Private

collection. Photo Courtesy of Sarah Ayala

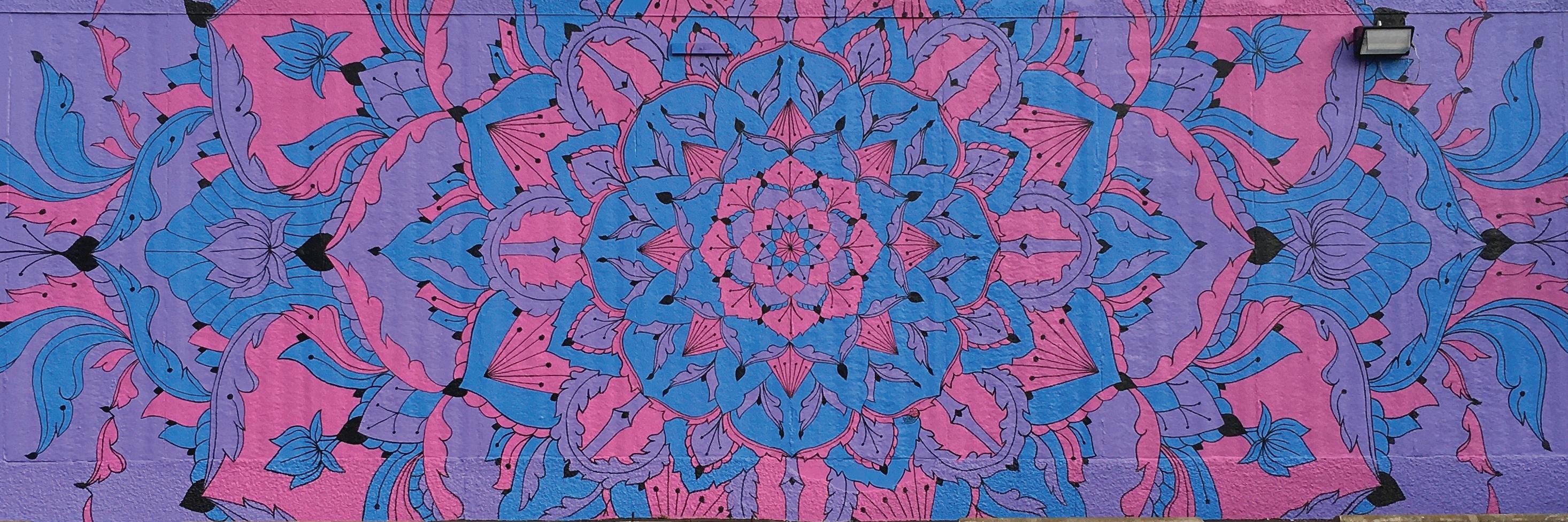

What is Sarah Ayala currently working on? A mural for Sundance Square for January. It’s for a project called T.I.M.E. in collaboration with Artspace111, including a series of murals from several artists. “I have free range on the mural design, which is relatively rare, so I need to figure out what type of message I’d like to send with it,” Sarah says.

She just finished her first installation piece for the Art Tooth’s micro-park in the SoMa District (https://www.arttooth.com/art-tooth-at-soma). That work is based on socio-economic topics from the past two years, including her cake-sculpture pieces that refer to stimulus check amounts and the topic of women’s reproductive health including SB8 and how those two topics intersect to create our current ecosystem and culture here financially for women. This was installed mid-December and will be up for a few weeks.

She has always loved history, too, and would soon get into antique and vintage maps. When Sarah looks at a map, she doesn’t just see geographic locations — a whole world past and present, all of its history and ideologies, and stories of borders, open up to her. She was fascinated by maps and how they reflect our dependence on time. “You can’t map the lines of longitude and latitude without keeping time and the distance between them,” she says. “That’s why really old maps are inaccurate, you know, because they had no grasp of time in relation to distance.”

Also, she sees maps in relationship to ancient civilizations and mythologies, and more recently regarding land ownership, how borders are made. She is fascinated when she looks at maps and sees countries that do not exist anymore or states and cities that aren’t yet formed.

When she started working with the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in its community and education outreach department, her vocation as an art teacher came back to haunt her. She began working with youth at community centers around town. “And it really just came back to me,” she says giggling. “I guess [it’s] a secondhand high, an enjoyment from watching someone who thought that they couldn’t create.”

Before that, she used to give mandala workshops because they are meditative, calming and do not require any prior training in art. Consistent with all of Sarah’s vocational art practices, they are not above anybody while still rooted in history and rich in meaning. Through her mandala workshops, she rediscovered her love of teaching and bringing healing through art to others. “I guess before I started working with the museum, that was my first taste of really savoring watching someone get something out of art,” Sarah says.

The Amon Carter was the best community partner Sarah would say she has ever worked with. “It was a dream come true; it was meaningful, nothing about it was hollow; I worked with different age groups and community centers,” Sarah says.

Above: Amon Carter at CAN Academy mural project.

Photos by Paul Leicht

Left: Detail of private residence mural in Monticello.

Photo Courtesy of Sarah Ayala

She would go to after-school programs in communities with children who are not typically exposed to art museums. “So, we were kind of bringing the collection to them and basing an activity off of the program,” she says.

Sarah also works with the youth to create murals with them using their ideas and helping them create them. “That’s when I loved working with alternative schools because I went to an alternative school in high school so I connected with that daunting feeling of, ‘Oh, I just ruined my entire life at 16, 17.’” She knows now that is not the case, but makes sure the youth she mentors knows that too.

She also works with a nonprofit called Big Thought, working with adjudicated youth in a program called Creative Solutions. At the end of their summer program, she said the kids don’t want to leave. She has seen young men cry at the end of those programs, witnessing the direct impact it has. She loves the work and continues to do it. “Since I started working with the Amon Carter, I feel like I can’t stop doing it. Anytime I stop, I get burnt out with other stuff. Working with youth is an escape for me now because it is fun and so much more meaningful,” she says.

SARAH AYALA’S TATTOOS: “I have tattoos of patterns and mandalas, but I associate that with my interest in Eastern studies. I have my last name tattooed on the back of my head, and I think that’s my favorite. As women, that’s the first thing that is on the chopping block if we marry, and I wanted to keep it with me forever. I have several matching tattoos with my best friend that are also my favorites.”

Above Top: Enamel on plate. Referencing the gender roles within the Latin communities and self sacrifice of women for others. Above Middle: Cake sculpture in response to the economic state during the pandemic.

The 29-year-old also collaborated with Artes De La Rosa for a fundraising event for her 30th birthday in December, which supports the advancement of Latin culture through the arts while also making the arts accessible.

The dots of her life all started to connect — her teaching, her art, her conflicts as a youth — it all coalesced into her purpose, her quest as a community artist.

A gold chain hangs around her neck. The charm is a gold Jesus with a crown. It was her grandfather’s, who wore it most of his life. She thinks it could be nearly 100 years old and heard that members of her family were goldsmiths in Mexico long ago. “I am kind of superstitious about this necklace; if I am not going to wear this necklace, then I may not have a good day,” she says.

The necklace helps her to be brave when she enters the public sphere to serve the community in all the ways she does. It helps her erase the proverbial borders between her, her art and the children she lifts through that art, like the lack of sense of time did for ancient civilizations on early maps she studies. And if matches her outfit.