2 minute read

Chapter Seven The Advertising Perspective

by One Question

The Advertising Perspective

Sarah Parsonage One Question

Advertisement

Paula Bloodworth Uncommon Steven Keogh former Detective Inspector at the Met Police

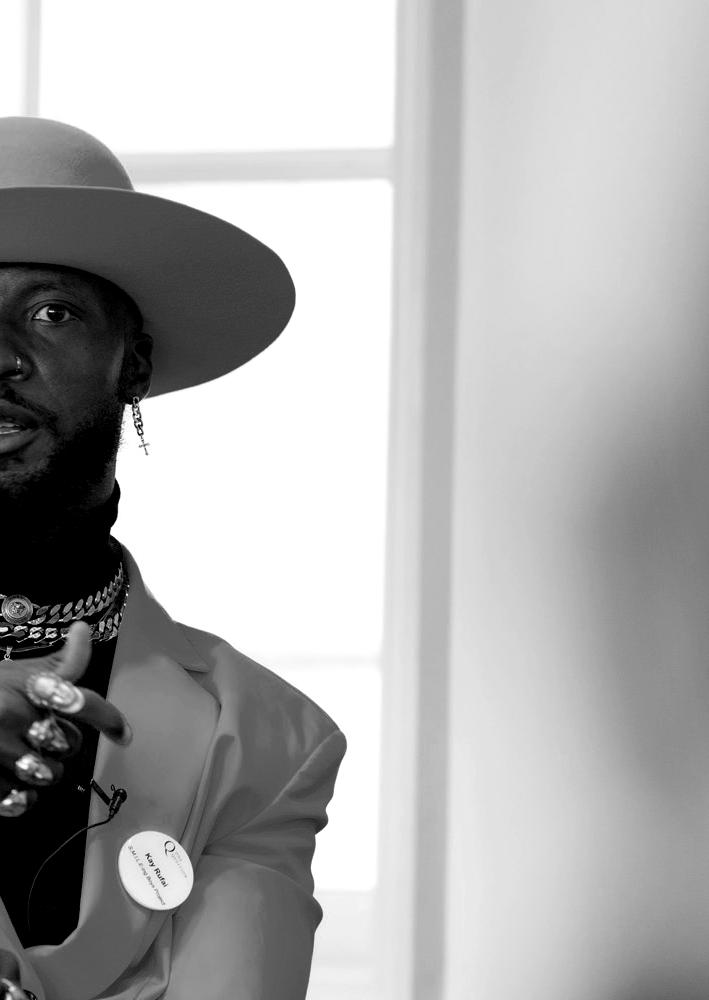

Kay Rufai Artist and founder of S.M.I.L.E-ing Boys Project

Posed as a thought experiment rather than a reductive quick-fix, One Question asked this session’s participants to apply their expertise to the Metropolitan Police.

“I don’t know how advertising can reverse the decline [in public opinion] right now. I think there needs to be action, there needs to be a change […] It feels like an internal problem. […] If there’s a few good people [in the Met Police], maybe we need to build them up and make them feel like they’re part of something. Then advertising within might be able to have a role.” Paula Bloodworth

In the light of numerous recent scandals, could the power of advertising be leveraged to rehabilitate one of society’s most foundational – and most controversial – institutions?

Defining advertising as using creativity to engender positive associations, Uncommon’s Paula Bloodworth felt that the Met’s core issues went deeper than a traditional campaign could reach. Suggesting in-house education as a first port of call, Bloodworth explained how defining the audience of a message can shape the message itself.

As we have seen, external solutions to internal problems are rarely sufficient; so, as the West Midlands Police’s first ever artist in residence, Kay Rufai was uniquely placed to make an impact from the inside out. Matching officers to local residents impacted by their investigations and using excerpts of dialogue to contextualise images, Rufai managed to position himself as an intermediary between the police and the communities they interact with.

As an institution, policing necessarily reflects shortcomings as well as strengths that extend far beyond its headquarters. Bakedin prejudices are just as likely to appear in officers as in the general public, and might even be magnified beneath policing’s lens of power. In this conversation most of all, the fiction of society’s institutions as separate from its fallibilities and fictions was starkly apparent. As such, education-assalve was more acutely important – its scope, far wider – than ever. “When I was doing this residency, [the officer pictured] was the commander. [...] The story that I’ve married him to is [from] a young girl, she’s 15, from a [very deprived] area of Coventry.. [...] Her story was incredibly heart wrenching, because she had an exam that morning – but at 4:30am, she awoke to the sound of the police chainsawing her door. [...] They were looking for firearms [...] but they didn’t find any, and that was it. She never heard from the police, the door was never fixed. And there’s the public fallout because she lives in a council estate, and [the neighbours] think, well, [the police] found something no matter what you tell us. [...] You can imagine how somebody under such stress would perform in an exam where she couldn’t even [explain] why she was late, and that had a significant impact on her life.” Kay Rufai