9 minute read

I Think I Can— Lois Lenksi’s Pen and Life Illustrated The Little Engine That Could

I Think I Can

LOIS LENKSI’S PEN AND LIFE ILLUSTRATED THE LITTLE ENGINE THAT COULD BY TOM STAFFORD

On Wednesday, June 16, 1915, three members of the Lenski family collected four college degrees.

Lois, the fourth of five children, was conferred a bachelor of science in education and a teaching certificate that morning at The Ohio State University’s castle-like Armory. The middle child, Oscar, received two degrees: a bachelor of architecture from Ohio State and a bachelor of arts from Bexley’s then all-male Capital University. In a way, their father, the Rev. R.C.H. Lenski, did the same. His first degree was a doctorate of divinity conferred by Capital, his second, the degree of pleasure he took from knowing two of his children had secure futures ahead of them.

Or so he thought.

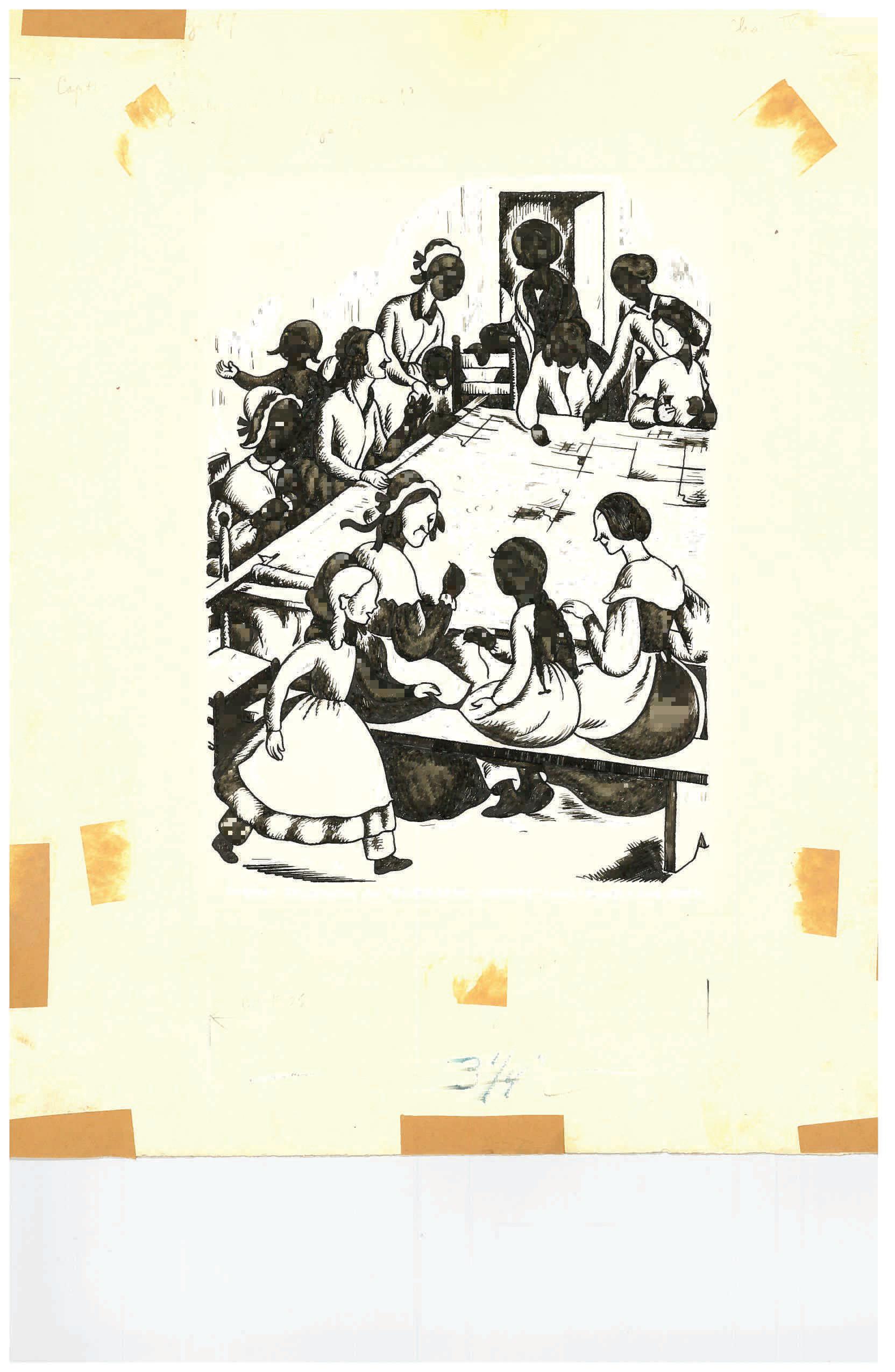

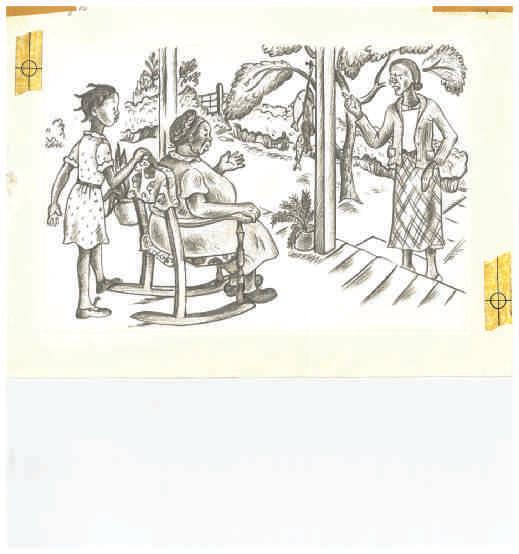

Above: Lois Lenski signing books at Springfield's Warder Public Library in 1953 on the occasion of her 60th birthday. Left: Original illustration from the 1931 book Grandmother Tippytoe, ink drawing with color by Lois Lenski.

Soon, the quiet Lois—who had loved children since her own childhood; who had in college worked part-time on summer playground programs for disadvantaged Columbus children; who had translated French and German folk tales to tell to neighborhood children; and who had read education pioneers Froebel and Montessori in her spare time— announced that she didn’t want to teach.

Her alternative: to study (of all things) art in (of all places) New York City. Few were more surprised than the young woman who would go on to become a Newbery Medalwinning children’s author while writing and illustrating nearly 100 books enjoyed by toddlers and teens from the 1930s through ‘70s. She “instinctively wanted and was looking for” the close contact with children teaching would provide, she writes in her 1972 autobiography, Journey into Childhood (quoted throughout this article). But “always another star loomed over the horizon, beckoning me.” YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN

Her father “vigorously” opposed her art school plans. “He said he could not help me financially, and if I went I would have to be entirely on my own. How I ever summoned up enough courage to make the break from home in the face of his disapproval,” she writes, “I do not know.” But from her father and mother she did inherit a work ethic as strong as The Little Engine That Could, the Watty Piper children’s classic she would illustrate in 1930. Like that engine’s, her struggle would be largely alone and uphill. In her first year at New York’s Arts Students League, Lois lived the life of a cash-strapped graduate student, scrimping, sharing a room and working for pennies apiece illustrating Christmas cards. But all this, she wrote, “made me realize how much creative work meant to me and how important it was to get more training.” In year two, while rooming with cousin Clara Lenski, an aspiring violinist, she took a free illustration class at the School of Industrial Art from Arthur Covey, who had taught at the Chicago and London art institutes and had assisted the two main painters awarded the Bronze Medal for their mural for the 1914–1915 Panama Pacific Exposition. PUTTING IN THE WORK

Lenski then picked up money assisting the widowed father of two at the Christmas toy shop at Lord & Taylor’s department store. The next year, 14-hour days on that project and school landed her in the hospital with influenza, reminders of a health made delicate by two infections that almost claimed her life in childhood: membranous croup, at age 3, and pneumonia five years later. After five years in New York, she spent two at London’s Westminster School of Art, where she earned her first money illustrating books but continued to live a solitary, sometimes lonely, life. The girl her mother admonished for being so shy did stop in on Covey’s late wife’s family there, then married the man 16 years her senior in 1921, two weeks after returning to the United States. She soon felt a shock as great as the one she had given her father. “One day early in our marriage, I complained to my husband that I had no time for my creative work, that the housework was absorbing me completely. To my surprise, he was completely unsympathetic. He replied, ‘Your job is the home and the children. They come first.’” When she asked, “What about my work?” the response was, “That’s up you. You’ll have to find the time,” just as her father had told her she would have to find the money.

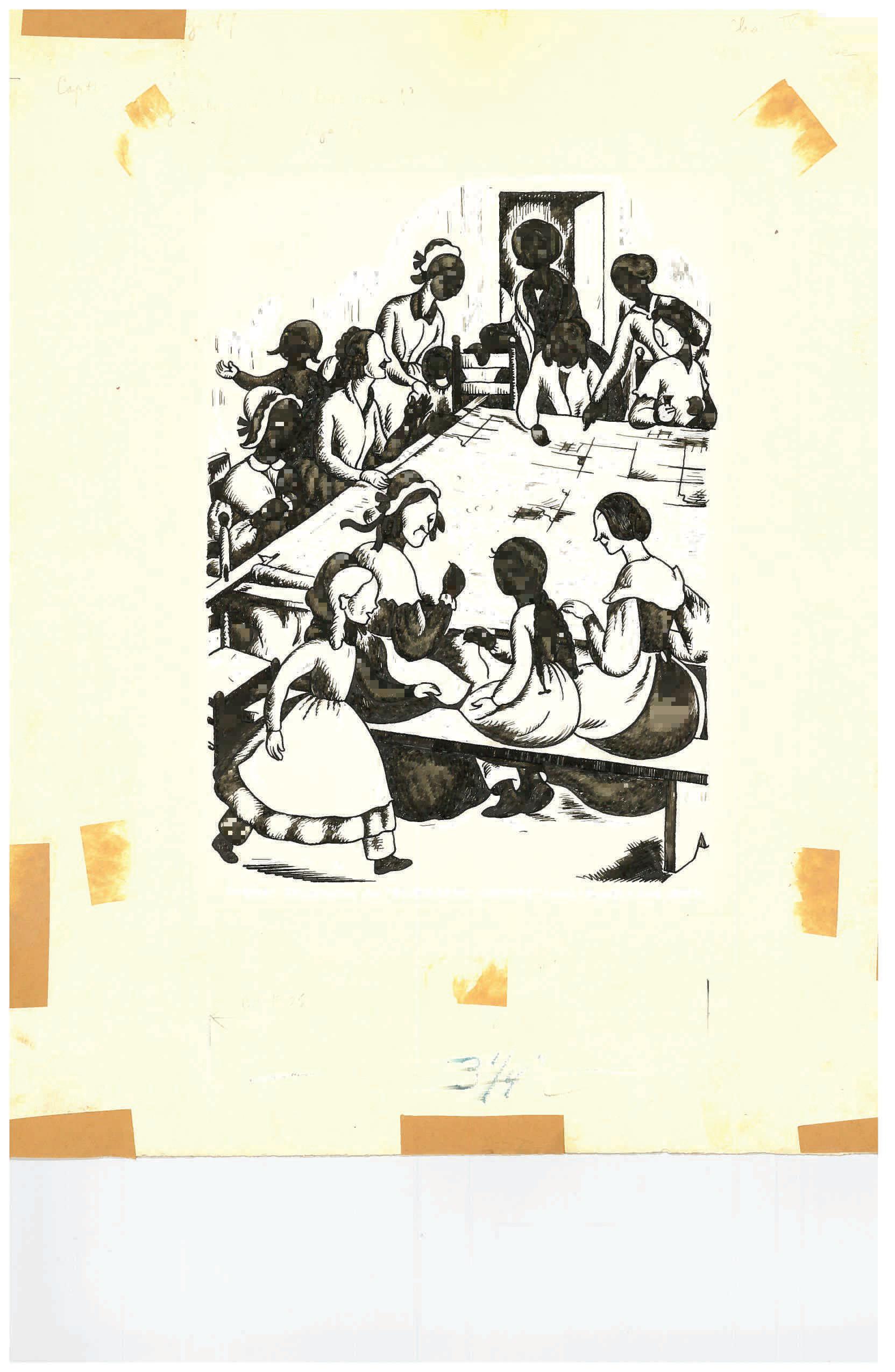

A black-and-white line drawing by Lois Lenski for a 1936 book, Phebe Fairchild: Her Book.

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED

At first angered and tempted to rebel, she ultimately fell just short of thanking her husband. “In offering me no aid in my struggle, he helped me to realize that I was truly possessed by this creative demon and could not and would not give it up.” As the children grew, she squeezed in more art lessons in New York. Then, five years into their marriage, she obtained an Overland car that gave her the freedom to take her easel to the countryside or travel to City Island’s Orchard Beach, where she found “seething masses of humanity” to paint. In 1927 and 1928, two fictionalized accounts of her childhood were published: Skipping Village depicted her years in Anna, Ohio, and A Little Girl of 1900, her years in Springfield, Ohio, where she was born (and where the children’s library is named for her). Lois gave birth to son Stephen Covey on Feb. 8, 1929, four months before the family relocated to a 113acre farm in Harwinton, Connecticut, they called Greenacres. The move was made considerably less idyllic because the home lacked electricity, which she said set housework “back to the dark ages.” MR. SMALL AND DAVY

Still, Lenski produced a dozen picture books and half a dozen early storybooks during the following decade, many in a remodeled and later expanded coffin-making building at the side of a hayfield. Book ideas she once struggled with “came on wings” and “were legion,” she writes: “If only one had health and strength and wisdom enough to put them down on paper.” And she began to see the creative force not as demonic but as “a higher power working through us. In consequence, the use of our gifts becomes not a selfish pleasure (selfishness a trait to be regretted) but the holding of a sacred trust.” During that same decade, she added a dozen books about historical children for preteens, all meticulously researched and two recognized as Newbery Honor Books. Wedged in were 10 books in the Mr. Small series, inspired by Stephen's childhood and loved for decades by children. The same audience would enjoy seven Davy books written from 1941 to 1961, inspired by and named for the step-grandson who summered with her. But in the early 1940s, a series of harsh Connecticut winters had taken its toll on her unsteady health. Finding herself unable even to sit comfortably in front of her easel, she followed her doctor’s advice to winter in the more temperate South. With son Stephen off to prep school, she was freed from the responsibilities of child care at the same time she was emerging from a chill shadow she addresses with unapologetic frankness in her autobiography. The increased importance of writing in her work “took me out from Arthur Covey’s influence. I was no longer his pupil, I was going in a new direction— a direction in which he could not follow, to guide me. So, I had to make my way alone”—again, but at least not with hindrance.

“I had learned in the early days to keep my work outwardly unimportant. … I wanted to avoid contributing to a feeling of jealousy. I could not bear to have a cherished idea of mine thoughtlessly condemned and trampled underfoot.” DOWN SOUTH

Her first winter in Mississippi, children gathered around her as she painted. Soon, the woman who had written first about her own childhood, and then about those of her own son and children of history, was writing Bayou Suzette, the first of 17 regional books that would both inspire her and teach her about the nation’s cultural landscape. “On my trips south, I saw the real America for the first time. I saw and learned what the word region meant as I witnessed firsthand different ways of life unlike my own.”

Above: Photograph of Lois Lenski taken in 1948. Inset: Lois Lenski, age 4.

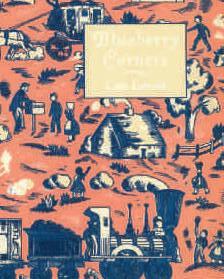

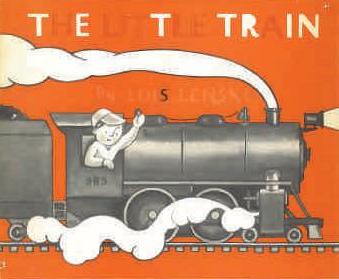

The dust jackets for three of Lenski's most popular books, Spring Is Here, Blueberry Corners and The Little Train.

Strawberry Girl, the second of her regional books, was set among the horse people of Florida and won her a Newbery Medal in 1946. As important, her practice of living among the people she was writing about, much like an embedded reporter, was balm for loneliness.

While working on Cotton in My Sack, she writes, “The cotton people were my people. I was warmed by their kinship and happy in the thought that I belonged there. …To merit the confidence these people spontaneously placed in me has been a rich experience indeed”—one that seemed to comfort her, body and soul. “One of the best cures for pain, illness and physical discomfort is creative thinking,” she writes. “It fills one with a sense of well-being, an indescribable joy which carries one’s thoughts and imagination along, so that one’s body can be forgotten. Creative effort lifts one above the sense of the corporeal body.” REGIONAL BOOKS A HIT

There was one more crucial element about the regional books written from 1943 to 1968 and the dozen that followed for younger children in the Roundabout America Series—a thing that would have pleased her by-then deceased father. In accepting one of her Newbery Medals, she said, “I am trying to say to children that all people are flesh and blood, and have feelings like themselves, no matter where they live or how simply they live or how little they have. I am trying to point out that people of character, people who are guided by spiritual values, come often from simple surroundings and are worthy of our admiration and even our emulation.”

The woman who had resisted classroom teaching was, through her art, trying to teach children to love their neighbors as themselves.

Tom Stafford spent 35 years as a reporter at the Springfield (Ohio) News-Sun, 20 of those writing more than 1,000 local history stories for weekly publication. He continues to write a Sunday column for the paper in retirement and does freelance reporting for WYSO in Yellow Springs.

LEA RN MORELEARN MORE Journey into Childhood: The Autobiography of Lois Lenski was published in 1972 by the J.B. Lippincott Co. two years before the author’s death. Lois Lenski: Storycatcher by Bobbie Malone “follows her development as a writer and as an artist, and it traces the evolution of her passionate belief in the power of empathy conveyed in children’s books. Understanding that youngsters responded instinctively to narratives rich in reality, Lenski turned her extensive study of hardworking families into books that accurately and movingly depicted the lives of the children of sharecroppers, coal miners, and migrant field workers.”