6 minute read

Putting Co-Design into Service Design–the AT Navigation Program

Kathleen Martinez, Occupational Therapist and AT Peer Support Lead AT Chat, Independent Living Assessment (ILA)

Having worked in caring, education, support coordination, and therapy service roles over the past 10 years, I have seen the wealth of knowledge a person with lived experience can bring to the table when it comes to service design. The role of ‘service design’ and ‘co-design’ can be traced back to 1970, and has gained momentum over the past 10 years, with the variety of service design education programs increasing1. Co-design is often viewed as a ladder of participation of how consumers are involved in the design of a service or product.1 Consumer involvement is transforming from being ‘informed’ and ‘consulted’ to more active roles of ‘co-design’, ‘co-production’ and ‘co-delivery’ of the service.

Co-Design and OT Practice

The underpinnings of co-design strongly resonate with occupational therapy teachings. Working from a strengthsbased model focused on building capacity, occupational therapists explore the barriers and facilitators that service users encounter in their daily life–and then work with them to create strategies, interventions, and evaluation reviews that help them progress towards achieving their goals. And then the whole process starts again. Of course, it is not as black and white as that, especially with changes to serviceprovider operations, and government policies and funding. In these cases, practitioners can feel like bystanders, with many factors beyond their control. So what can we do about it? We can implement and advocate for co-design, to improve the experiences of service users and understand the services themselves.

Co-Design with AT Chat

AT Chat, an initiative of ILA, is a peer-led, co-designed online community for assistive- technology (AT) users. AT Chat’s mission is to share the lived experience and knowledge of AT users with the wider AT community through peer support, so individuals can become confident and capable to make AT decisions to ‘Live, Play and Work!’

Thanks to an NDIS Information, Linkages and Capacity Building Grant, and a passionate community of AT users, AT Chat wanted to include AT users, experts, practitioners, and the wider AT community in the design, development, and review of its service offerings to ensure it discovered ‘what good looks like’. To achieve this vision, the Living Labs co-design methodology of exploration, experimentation, and evaluation was applied to get the best possible outcome for the user.1 Living Labs with the AT Community

The early exploration work began with user surveys, focus groups, and think tanks. It explored the current state of AT service delivery, which focuses on the AT user as the ’end’ user–then proposed a future state, in which peer support would be valued as ‘part’ of the AT servicedelivery process. This innovation received overwhelming support from all stakeholders.

The next phase in the exploration identified and described the work roles of AT users, practitioners, service providers, and suppliers within traditional AT service delivery steps2. A key part of this process was translating traditional AT service delivery steps into terminology that reflected the voices of AT users and their roles as peer supporters.

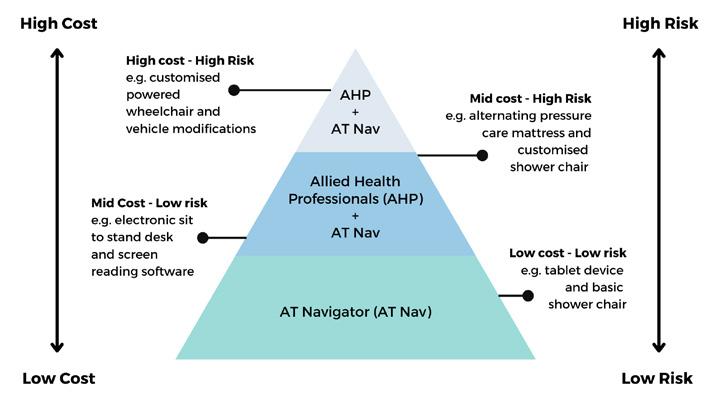

It was acknowledged early in the phase that AT was becoming more accessible, with online shopping and big box stores offering mainstream and off-the-shelf AT products. The AT community strongly identified the need to consider the safety and risks that AT may pose to AT users, and the instrumental role of allied health professionals in AT service delivery.

The experimentation stage of the Living Labs began with User Driven Prototyping

Figure: AT risk and roles

(UDP) sessions to identify how the AT community would like to connect. The sessions confirmed an online service and portal as the preferred method of service delivery. This online approach allowed the peer support solution to be launched and tested remotely as a pilot program in 2020, during the challenging conditions of COVID-19.

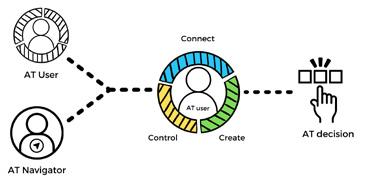

The Connect Create Control Model of Peer Support was co-designed using data from the exploration stage, and contributions and evaluations from pilot participants, the university research partner, and accessibility consultant. Pre-pilot evaluations were conducted with participants, and weekly supervision sessions conducted with AT Navigators.

The dynamic process of the experimentation stage led to the next iteration of the AT Navigation Program. The word ‘navigate’ means to travel on a desired course after planning a route. The word ‘facilitate’ means to make things less difficult. The AT Navigator works alongside the AT user to facilitate the process of finding an AT solution through planning. The partnership aimed to empower the AT user to take control of the knowledge they gained, build their capability and confidence to act upon the AT information and apply it to their individual circumstances3 . These actions may include seeking further support or assessment from an alliedhealth professional, completing further research before buying their AT, and discussing training options or funding applications with service providers and funders.

From Best Practice to Next Practice

Evaluation is the final stage of the Living Labs to measure the potential impact and added value created by the innovation. The pilot provided positive indicative evidence about the value of peer support from the perspective of AT Navigators, AT users, and the knock-on benefits for service systems. It also highlighted the need for an increased emphasis on workready skills for AT Navigators, such as time management, and embedding a community of practice with alliedhealth supervision.

Based on an independent implementation evaluation, four key implications were identified for next practice4 . 1. Active co-design of AT services meets human rights and good practice benchmarks required by contemporary services 2. Foregrounding AT users within program design and delivery brings a range of positive outcomes and possibilities for the way services are delivered 3. AT users have substantial untapped potential which brings tangible outcomes for other AT users, health professionals, service providers, and for society 4. Development of paid roles and pathways to recognise the skills of AT users and AT communities has potential to improve AT user self-efficacy and contribute to the AT workforce

Although the key implications focus on AT service delivery, each point can be applied to all servicedelivery settings. The AT Navigation program centres on the AT user, and is built on foundations of co-design, bestpractice approaches, and creating valued roles for people with disabilities to share their experience and knowledge, building increased leadership and influencing opportunities. About the Author Kate has broad experience working in the disability sector in the community, schools, homes, and workplaces. Kate has a passion for working with people and communities to incorporate their lived experience and expertise into service design through co-design.

AT Navigation Peer Support Journey

References 1. Evans, P., Schuurman. D., Ståhlbröst, A., and Vervoort, K. (2017). Living lab methodology handbook: User engagement for large scale pilots in the internet of things. 2. Walker, L., Astbrink, G., Summers, M., and Layton, N. (2012). Assistive technology and the NDIS: The ARATA ‘making a difference with AT’ papers. 3. Harris, J., Springett, J., Croot, L., Booth, A., Campbell, F., Thompson, J., et al. Can community-based peer support promote health literacy and reduce inequalities? A realist review. Public Health Res 2015; 3(3). 4. Proctor et al. 2011. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and policy in mental health, 38, 65-76.