8 minute read

On George Elroy Boyd

Or, Reading plays as social work(s)

BY GEORGE ELLIOTT CLARKE

Advertisement

The premature death of George Elroy Boyd, aged 68—in Montreal, on July 7, 2020—received even less notice than his quiet—almost serene—demeanour tended to arouse during his life. Despite having become the first African-Canadian national news anchor upon the birth of CBC Newsworld in 1989, nearly 21 days passed before Boyd’s obituary was posted, commentaries circulated, and the accolades bruited.

However, though the African-Nova Scotian playwright and journalist loved to see his stories staged and to tell the stories of others through the TV lens (and screen), he was, personally, so affable as to be nearly self-effacing and so modest as to seem mute. Evidently, he was a writer who let his characters voice his quandaries and who let his plots disclose the infernal dilemmas of being Black—and “Bluenose”—in a province sodden with spirits (spectral and liquid) and often dripping salty water, salty tears, or salty blood.

Born in 1952, Boyd grew up a North End Haligonian, in a part of town known for iconic boxers, iconoclastic rogues, and diets heavy on sauerkraut and mackerel, fish-n-chips and ale, and mustard and malt vinegar.

Boyd spent his youth among a macédoine mix of neighbours: Acadian, Black, Brit, Chinese, Mi’kmaq, Newf, plus immigrants from round the globe, as well as peripatetic sailors, anchored in Halifax a spell and then anchors aweigh’d again. Boyd’s North End peers back-in-the-day belonged to the struggling classes—from the jobless to the part-time worker, from the pensioner to the welfare-recipient, and from the poor to the worse-off, that is to say, anyone who appeared in police reports as having “No Fixed Address.” While Boyd may have rubbed shoulders with charismatic toughs, rough-and-tumble athletes, cigar-chomping philosophers, and I-don’t-take-no-guff-from-anyone women, he also would have encountered the proud citizens of Africville as they went to earn livings as maids and day-labourers, and he would also have heard their specific and pictureseque lingo—African Nova Scotian Veracular English—right along with the four-letter-word-only vocabulary of the sailors and the raw, ear-scalding Billingsgate of the addicts, the addled, the bawdy, the crooks, the derelicts, and the drunks. In becoming a playwright, he couldn’t have asked for a better schooling, so to speak, than in the real earthy, concrete, pungent, and analytical palaver of citizens who were often drop-outs or who’d been prevented—by poverty, racism, sexism, classism— from getting much further than Grade 3, let alone Grade 9. They may not have parleyed the then-young Queen E’s English, but they had street smarts, the guttural grammar of workplace and pub, and the outrageous proverbs derived from gossip or tall tales as exciting as any soap-opera (so you laugh until you bust your guts and the tears burst out).

This was the milieu to which writer Boyd learned to cup an ear and to cut his teeth on. But he’d also have nosed through a riot of smells: salt-scent harbour, Oland’s beer brewing, Piercey’s fresh sawdust, Moirs’ chocolates, “Maaaaaaackerel” shilled by Prestonian fish merchants, home-chimney smoke, frequent fog, Ben’s bread stacked for delivery, the Enn-Ess slaughterhouse blood, cigarettes puffed from lips and gum crackled in jaws, and, of course, sometimes, the aroma of the city dump.

Now, a playwright and a social worker may seem worlds apart, but Boyd understood that their skills—if unrecognizable to bankers—are similar: attention to narrative, to life stories, to the wincing that Pain wins, to the repugnance that Oppression merits, and to recognize that every psychology is an extract of blood and guts, and that Sociology itself is the mealy-mouthed sprinkling of euphemisms to gussy up sordid, misshaping, deforming, and unbeautiful class warfare.

I think that’s what Boyd’s plays undertake: to explore underbelly and backwater, to tunnel—deep drill—his pen into History; to reveal a Black Nova Scotia of handouts and fisticuffs, of maternity-ward screams, of the goddamned who struggle against torments and flounder in waste, and of the godawful, two-faced, inexpiable elites of school guidance councillors, welfare potentates, pogey bureaucrats, criminal (adj.) lawyers, and bogeyman cops. His is no mere clinical irritation because Boyd knows that all is still nunc pro tunc, that our “now” is exactly the same as our “then.” His plays are where New York encroaches upon New Scotland—and Harlem relocates to Halifax.

His plays holler back to “You, the Government of Canada, who are always saying that ‘We the North’ is the land of true freedom and equality, but I call you out as a liar and a hypocrite!” His dramas voice rebuke and righteous calumny.

Africville backyard scene, featuring a boy with his bicycle and a full clothesline of laundry.

Photographed by Bob Brooks, 1965. Nova Scotia Archives.

In plays like Gideon’s Blues and Consecrated Ground, Boyd stages boldly, unswervingly, what he views as the peculiar, treasonous weakness of Black—Africadian—men. In the first play named—which is also the first of his to be staged (in 1985), Boyd presents a portrait of Gideon, a university graduate and father and husband, who cannot find a job commensurate with his education. Not in Halifax! So, Satan materializes in the shape of a Newfoundland-based drug kingpin and promises Gideon the moon in exchange for, well, you-know-what. Tired of living with his wife and son in his mama’s house, and weary of feeling that he’s less than a man, Gideon cuts a deal with the Devil and is soon doing boffo biz supplying crack cocaine to the “hood.” Gideon blows up; he becomes a big-time bigwig; but he’s also dissolving the Black community. Once his crack dealing poisons his own family, his mama puts him down like a rabid dog. It’s an extreme act, one that makes Gideon’s Blues a true tragedy.

Consecrated Ground is likely Boyd’s most famous play. It’s a vivisection of the moment when, thanks to Albert Rose’s 1962 recommendation, Halifax city bulldozers began—in 1964—to knock down Africville homes, city garbage trucks began to “relocate” Africville families, while city social workers arrived with promises (few kept) and city lawyers arrived with cash (not too much). By decade’s end, all the 400, mainly Black residents were “relocated” to slums and/or housing projects nigh downtown, thus obliterating a vibrant 150-year-old Black community. Boyd restages the historical event as a contest between the white socio/political class (social workers and municipal government) and the Africville clergy (also backed— in effect—by the Ladies’ Auxiliary). The other central conflict is between husband Willem and his wife Clarisse—or Leasey. They are both Africadian, but Willem desires “integration” with white Halifax, while Leasey values her generations-long homeownership and ancestry in Africville. The debate between the couple remains philosophical until a rat from the next-door dump bites and kills their infant son. Instead of blaming the city for the death of his son, Willem decides to sign away Leasey’s homestead and move. This decision likely terminates the marriage, but, having lost her son and home, Leasey now fights everyone—Willem, the Africville minister, and city officials for the right to bury her boy in “consecrated ground.” Maybe she wins. By play’s end, the Africville cleric sprinkles Africville earth upon the baby’s casket. But it’s winter, and the ground is wind-swept and iced-over. Moreover, bulldozers prowl still, destroying homes. Even if Leasey succeeds, her son will be buried amid a desolate waste. Too old to conceive again, and betrayed by Willem, Leasey’s future is bleak: childless, homeless, and perhaps penniless, but definitely stateless—I mean, adrift. Of course, the physical community is also lost, including the church, and so even the Africville Christians “lose” in their contest with diabolical, white, municipal authority.

Africville houses on either side of a hillside lane.

Photographed by Bob Brooks, 1965. Nova Scotia Archives.

Consecrated Ground was nominated for a Governor-General’s Award for Drama in 2000. Another play, Wade in the Water, was nominated for a Montreal English Critics Circle Award in 2005. Gideon’s Blues got adapted for TV and broadcast in 2010 as The Gospel According to the Blues. Boyd’s other honours include being a playwright-in-association with Halifax’s Neptune Theatre, a writer-in-residence at the Stratford (ON) Shakespearean Festival, representing Canada at a Pakistani theatre festival, and receiving an honorary diploma from the Nova Scotia Community College, and an Atlantic Journalism Award. Clearly, he rightly represented the polarities of class and gender and race on our shores.

Amid the droning doggerel of fog horns, so to speak, Boyd narrates, in his plays, the hard-won elegance of his women characters and the asinine greed of his black men for status and cash (neither of which they get to keep).

These portraits are poignant, gritty, and as harsh as the display of a dead deer roped to a car hood. Thus, Boyd deserves commemoration, to have his plays mounted again and again, to be celebrated as a fine African-Canadian playwright because of the truth that his characters—scruffy sad sacks and renegade angels—gab like us, gabble like us, blab like us, babble like us, rap like us, bullshit and banter and toss around balderdash and yinkyank like us. Boyd does what Shakespeare does: gives us the vox populi, the way dudes and dames really speak. No longer subsidiary can be our applause….

GEORGE ELLIOTT CLARKE was born in Windsor, Nova Scotia, in 1960. He grew up in North End Halifax, and had (former) social worker and (democratic) socialist Alexa McDonough as his kindergarten teacher. Clarke is now a significant Canadian literary figure, a scholar of AfricanCanadian and Africadian (African-Nova Scotian) literature, and a tenured professor at the University of Toronto. Appointed to the Order of Nova Scotia in 2006 and, in 2008, to the Order of Canada at the rank of Officer, Clarke’s latest poetry work is Portia White: A Portrait in Words (Nimbus, 2019) and his latest CD, with musical group The Afro-Metis Nation, is Constitution (2019). He served as Poet Laureate of Toronto (2012-15) and Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada (2016-17).

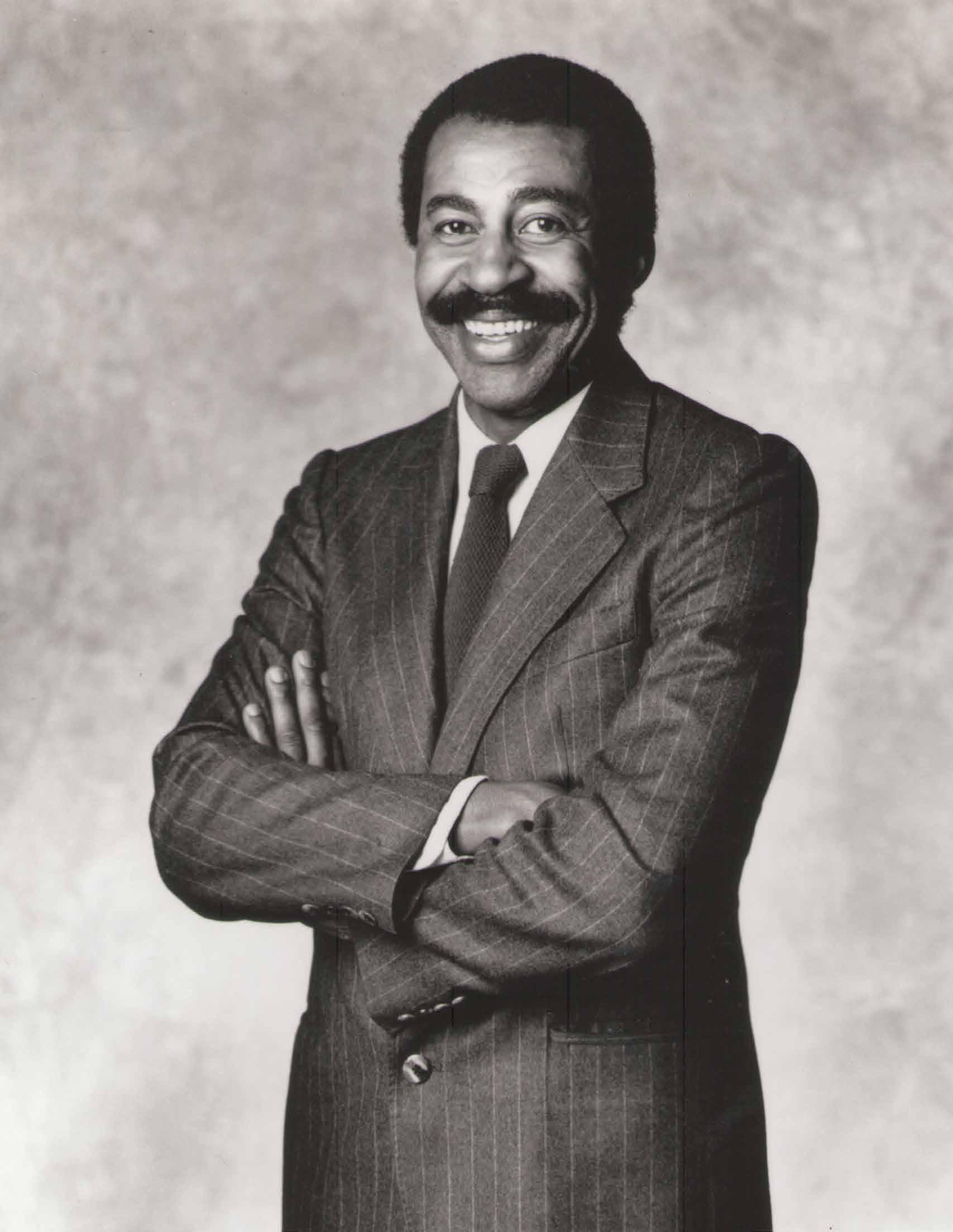

Portrait of George Elroy Boyd, , provided by his family