31 minute read

Reflections: On Strike MoMA, Caribe Fractal and Decolonial Feminisms as Political Arts Practice

Reflections: On Strike MoMA, Caribe Fractal and Decolonial Feminisms as Political Arts Practice

Stephany Bravo and Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vásquez

This piece is an assemblage of two voices meditating on the Strike MoMA protests, the work of digital humanities/material project [Taller] Electric Marronage, and the ways that decolonial feminisms allows for a complex understanding of our roles and commitments to practices that span across and beyond western institutions (including museums and universities). By tracing these events and experiences through a decolonial feminist politic, we aim to render transparent the tangle of insurgency and complicity that we negotiate as Black/Latina scholars and organizers within dominating institutions. The essay further considers the content and context of the art exhibit “Caribe Fractal/Fractal Caribbean” by José Arturo Ballester Panelli and how fractality, ecology, and the sacred are linked to human living beyond capitalism and fragmentation. In the wake of the pandemic fractality, ecology, and the Sacred are tools for practicing intersubjectivity and relationality.

Keywords: Decolonial Feminisms / Fractality / Intersubjectivity / Pandemic / Relationality / Strike MoMA / [Taller] Electric Marronage / Visual art

Fractal 1: Introduction

On Friday June 4, 2021, members of [Taller] Electric Marronage were invited to share our work with the StrikeMOMA Working Group. Strike MoMA, a twophase, stakeholder-led decolonization process for MoMA without the authority of MoMA, consisted of orientations, training sessions, writing projects, public arts, campaigns, and protests.1 Additionally, Zoom sessions optimized reach for those unable to physically convene. On the ground and online, those who

©2023 Feminist Formations, Vol. 35 No. 1 (Spring) pp. 30 –46

joined the efforts of Strike MoMA learned about the museum’s board members and their “ties to war, racist prison and border enforcement systems, vulture fund exploitation, gentri cation and displacement of the poor, extractivism and environmental degradation, and patriarchal forms of violence” (StrikeMOMA Working Group, n.d.-b). Participation by those in attendance premised a larger understanding that both museums and universities are essential aspects in the civilizing discourses of colonial modernity and active participants in (re)producing the material structures of colonialism, that in turn, makes those of us who work within their walls complicit (StrikeMOMA Working Group, n.d.-a). Our work as scholars and as curators of Electric Marronage (a dual-university funded project) is contingent on nding ways to both escape from and work within institutions marred by histories of colonialism, exploitation, racism, and dispossession in order to subvert the historied co-optation and chicanery of higher learning institutions. What follows is a decolonial feminist re ection on the complicity of museums and universities in settler colonial and extractivist logics and actions, the work of Electric Marronage within these sites of violence and power, and an examination of the physical gallery exhibition and digital gallery exhibit we curated in 2020, “Caribe Fractal/Fractal Caribbean” and “En Tiempos de Pandemia/In Pandemic Times” by Afro-Puerto Rican photographer José Arturo Ballester Panelli.

Fractal 2: Electric Marronage

[Taller] Electric Marronge presents itself as a group of Black, brown, queer, writers, artists, and organizers. Its members, the electricians, have strategically taken it upon themselves to plot points across the escape matrix through petit marronage –stealing away on the electric platform in order to connect, abscond, and reveal.2

Established in 2018 and made public in 2020, the work produced through Electric Marronage occurs with the understanding that we are products of histories and infrastructures engulfed in violence from enslavement to genocide, those affected, speci cally Black and Indigenous peoples have not received their due reparations.3 Electric Marronage turns to the digital realm, brings together those at the underside of colonial modernity to engage in dialogue through workshops, conversations, and exhibitions which take seriously our collective lived realities in the making of liberatory futures. We are not without contradiction, as Electric Marronage opens a juncture in the digital realm, our host institutions continue to occupy Indigenous territory and dispossess Piscataway, Susquehannock, Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples (Miner). As Nelson Maldonado-Torres remarked during the StrikeMOMA Working Group meeting, “some of us supporting the strike are curators or educators—scholars who work

in museums or universities—and I don’t think that we can so easily disentangle ourselves from extractivism and what it means” (StrikeMOMA Working Group, n.d.-a). We cannot fail to acknowledge or critique our institutions enduring and multifaceted ties to modernity’s agenda in the attack on Black and Indigenous life and this complicity is particularly profound in those individuals who fail to imagine or provide venues to live beyond modernity’s hold.

Pivotal to Electric Marronage’s decolonial turn is the powerful force of the imagination as we maneuver within sites of power, that is, we believe that decolonial reparations consists of responding to the insurgent calls for land back, the demands to repatriate stolen artifacts and remains, and the call to end the crisis of gender and sexual violence that disproportionately affects Indigenous women and girls. These actions are part of a material reparation and are essential to fueling a reparation of the imagination which entails “an ethical demand for decolonial love re/produced through technologies of relations across difference, and the labor of imagining other ways of being human in the modern/colonial and settler colonial world” (Figueroa-Vásquez 2020, 197). Electric Marronage comes to fruition through a reparation of the imagination fermented by electricians, descendants of those previously denied, arguably still denied existence in a profuse amount of systemic ways.4 Electricians carry their ancestral legacies of resistance and hash out strategies grounded in the labor of love across relations within and outside of the modern/colonial and settler colonial world. Electric Marronage is bound by four rules of fugitivity: escaping, stealing, feeling, and whatever. Marronage— ight from slavery and conscription for either brief or permanent periods of time—serves as our point of departure. Together, these rules and strategies guide us and help us conceptualize how to conjure and build upon the experiences of ancestors who resisted in an array of ways that have led to our ultimate existence.5

Guided by these rules and strategies leads us to the understanding that institutional access cannot be the endpoint if it leads solely to the perpetuation of colonial logics and practices. There are a few things that we have learned from our trajectories within institutions of power as we pay close attention to the path already paved by practitioners of decolonial thought. For one, Audre Lorde’s words illuminate the complexity of our roles as historically excluded individuals making our way into the master’s house, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change” (Lorde 1984, 112). The work produced within Electric Marronage is sustained by a group of Black (Caribbean and United States) and Latina women, with contributions from Asian, Arab, Paci c Islander, and Indigenous scholars, writers, and organizers. In short, Electric Marronage requires more than the tools and practices that the university offers to remain sustainable and have an impact. That which is required can be found in Laura E. Pérez’s (2010) decolonizing politic where those at the underside of colonial modernity bring forth categories

of “knowledge and existence” that were “previously unseen marginalized and stigmatized” –epistemologies pertinent in the survival of our lineage and kin. The taller is cognizant (as the name suggests) that organizing and having an impact must be premised on logics of resistance including theft and fugitivity.6 Across the digital humanities, Electric Marronage seeks to practice the interest of life beyond survival by accounting for old, hybrid, and emerging strategies inside and outside of academia. Electric Marronage recognizes that the tools that women of color need and rely on are not luxuries—we leave no stone unturned when it comes to imagining and building futures.

Fractal 3: “Caribe Fractal/Fractal Caribbean”

The question explicit in Strike MoMA remains: what does a postMoMA future look like? The answer is not universal and cannot be if we consider the histories and stakes that each individual has to bear. Nevertheless, it is our belief that even when hyper visible, the work spearheaded by women of color is not given enough credit. This is particularly true in academic settings where there is often a push for sheer novelty, systemic devaluation of women of color feminist thought, and a rush to jargon not of our own making that cannot begin to grasp possibilities of abundance and strategy that women of color bring to their works (Christian 1987; Dotson 2016). If we center decolonial feminist thought and praxis, then we would come to understand that the postMoMa future does not begin after a distant colonial temporal order, but rather can and does exist right alongside us. We are here because someone before us chose to believe beyond colonial con nement.

Through a reparation of the imagination, Electric Marronage has conceived of numerous projects that plot points across relations inherent in lived experiences and realities. One of those projects was the curation of “Caribe Fractal/ Fractal Caribbean” by José Arturo Ballester Panelli during the spring of 2020.7

“Caribe Fractal” is an ongoing project by Ballester Panelli, an Afro-Caribbean artist based in Puerto Rico.8 Ballester Panelli’s work explores the ties between Afro-Caribbean aesthetics, histories, ecological systems and its diasporas through a multimedia approach integrating installation, photography, digital design, video, and sound. Caribe Fractal, as theorized by author Mayra SantosFebres and Ballester Panelli is a way to think beyond colonial cartographies that imagine colonial subjects and geographies as fragmented.9

In her 2019 Womxn of Color Initiatives keynote at Michigan State University (MSU), Santos-Febres used some of Ballester Panneli’s images to discuss how Caribbean fractality is both a way to think and talk about ecology and Afro-syncretic spirituality. It is likewise a Caribbean philosophy and Afrodescendant philosophy that traverses ideas of contradiction as the only vehicle for movement or transformation. Instead, Caribbean fractality re ects “nature, social organization, and artistic expression” that is multiple, varied, and related

(Santos-Febre 2019). For Santos- Febres, the fractal Caribbean is part of a whole, a cosmology rooted in the most microscopic aspects of the land and its organisms as well as a way of seeing, being, and enacting a worldview that is insurgent and deeply embedded within Afro-Caribbean syncretic and Sacred cosmologies including Santería and Lucumí. Caribbean fractality can be understood as part of a decolonial feminist imperative to see communities, political practices, artistic endeavors, and other acts as complex, interrelated, and necessary parts of transformation at structural, personal, spiritual, or community levels.

Initially, “Caribe Fractal” at Michigan State University was to consist of an exhibition at the MSU Museum and a four-week residency by Ballester Panelli which would have resulted in arts seminars and classroom visits to various Ethnic Studies and Art, Art History, and Design courses on campus. Additionally, Ballester Panelli was scheduled to conduct talleres on photography and fractality with students and community members which would culminate in a pop-up exhibition of student and community works at the MSU Broad Art Lab during the closing reception. As originally conceived, “Caribe Fractal” at MSU would immediately follow groundwork in Puerto Rico where Ballester Panelli alongside professors Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez and Estrella Torrez led the immersive experience of #ProyectoPalabrasPR (#PPPR).10 Working with Yagrumo Taller Experimental de Imágenes, #PPPR brought undergraduate and graduate students from MSU as well as third and fourth year students from Lansing’s Everett High School to Adjuntas and Santurce, Puerto Rico, for a communitybased study-away program during March 1– 8, 2020. The program’s goal was to foster an immersive program that attended to the learning of Puerto Rico’s culture, history, and politics through direct engagement with artists, organizers, and community activists. The second goal of #PPPR was to create an exchange, within two weeks of the students’ return to Michigan, we would host one or more of our artists, organizers, or activists to travel to MSU. This exchange would consist of a collaboratively designed paid residency that would act as a sustaining and reciprocal method of hosting, resource, and knowledge sharing.

Ballester Panelli was to be 2020 #PPPR exchange residency. However, on the last day of the #PPPR and Yagrumo Taller Experimental de Imágenes study-away program, MSU began procedures to return all its study-abroad and study-away students back to campus. Followed by an immediate lockdown, the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning to unfold in the United States. The rst case had arrived in Puerto Rico via a cruise ship on March 8th, the very same day that the students were boarding their ights to Michigan. On March 9th, as the university and the state began their unprecedented lockdown, FigueroaVásquez carried two large packages of 18"×18"×18" acrylic panels on her ight back to Michigan from Puerto Rico. The task was undertaken in efforts to ensure secure transportation of the delicate panels and to alleviate costs that would thereon be utilized for other community projects. During our separate returns to Michigan, we wouldn’t have fathomed the university’s refusal to provide an

alternative option for programming, the devastation on the horizon, or how the pandemic would impact our families and the communities to which we belonged. The precarity of Electric Marronage’s work through the university and warnings provided by Lorde, manifested themselves.

The Exhibit

In the face of the unprecedented effects of the pandemic, Electric Marronage reassessed the goals set in place and reimaged how this work could be shared amid a global pandemic. The transported 18"×18"×18" acrylic panels were safely tucked into a closet awaiting an installation date that would not come for months. On the surface, the transfer of the panels from the Caribbean to the Midwest documents the unrecorded labor undertaken by women of color who believe in the power of narratives as a transformative means towards survival across relations. This is particularly true when institutions begin to make cuts in programming that can be seen as vestibular to the epistemologies and priorities upheld by universities. However, the invisibilized efforts made by women of color demonstrates a breach, a crack in the order of things, and a refusal to

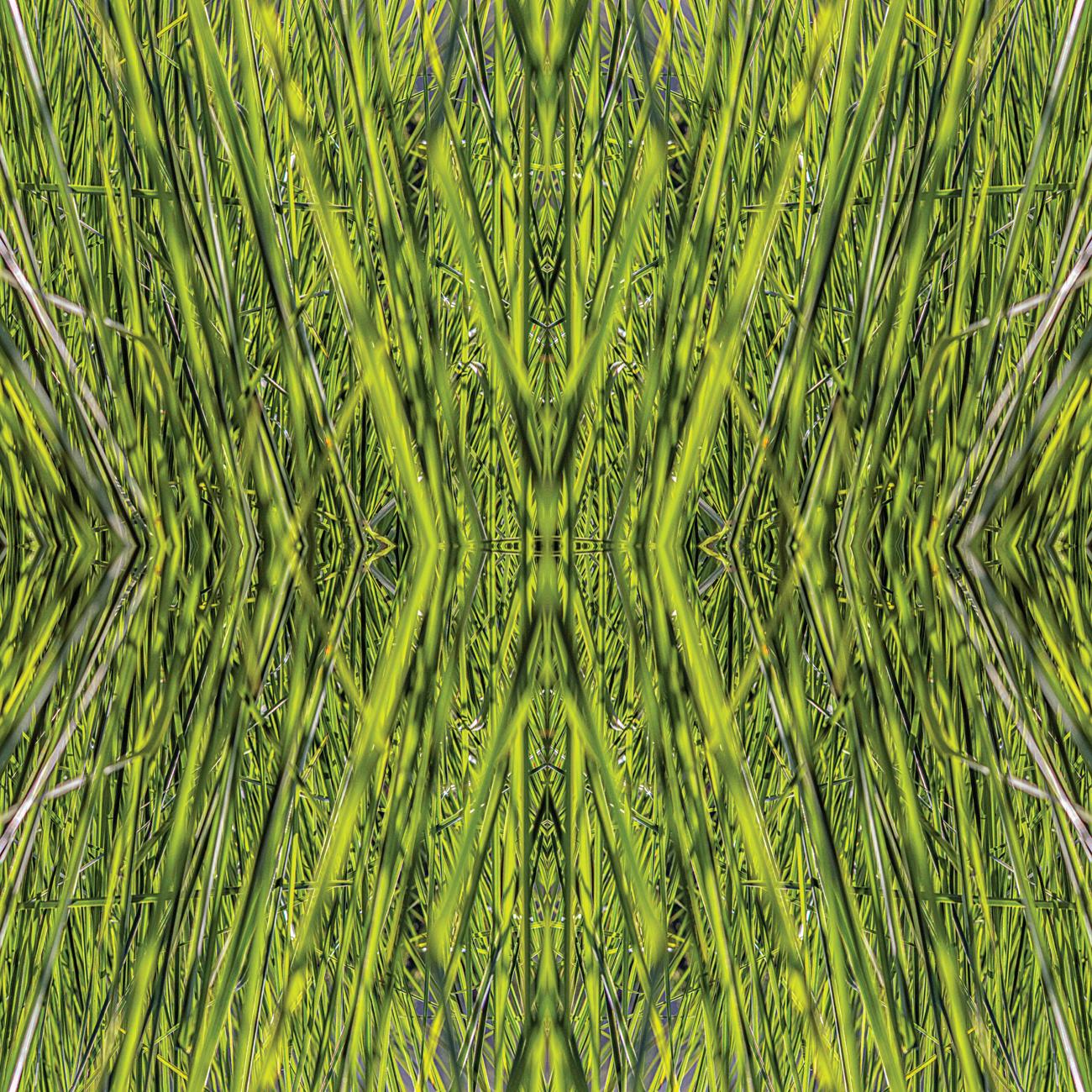

Figure I. José Arturo Ballester Panelli, From left to right: “Agua,” “Mercado,” and “Tierra,” Caribe Fractal, 2019.

acquiesce. The movement of bodies across waters detail forms of solidarities that are imbued by trust amongst kin. Fractality as a decolonial feminist imperative demonstrates practices of seeing and being, which generate grounding the selves in relations across difference. Forms of labor that occur outside of academic and cultural institutions underscore a commitment to artists’ practices, an appreciation of their material works summoned by devastation, and the epistemological shifts that their works cultivate and exchange through breaching and crossing.

The labor of love invigorated through Electric Marronage became especially crucial, in this case, during a pandemic that caused havoc on those historically excluded, marginalized, and ignored. These unrecorded acts culminate into the necessary ampli cation of powerful accounts of resistance that artists such as Ballester Panelli bring forth through their art. Furthermore, these acts allow audiences to have conversations about the status quo and tactics towards survival during a time when institutions delve into statistically understanding the unfolding pandemic through a static and limiting periphery interested in a “return to normal.” The inability of the ivory tower to promptly intervene during the pandemic ampli es how women of color have consistently returned to the work conducted on the ground—made paths across space and time to center on those who prove invaluable under the reckoning of catastrophe. Months later, when invited to participate in the conversations around the Strike MoMA, we considered the inextricable link between universities and museums as institutions that perpetuate settler colonial orders of knowledge and extraction. We re ected on our work in the gallery space at MSU in relation to a behemoth art institution like the MoMA. We thought about the ethics and practices that undergirded our work with Electric Marronage which were shaped by community, student, and fractal networks, and that of the MoMA as an extractivist and exclusionist institution. What could the MoMA become if it were to radically shift its modus operandi and attend to the histories, needs, and ethical demands of its community and those made most vulnerable by capitalist extraction and ongoing forms of dispossession and racism?

“Caribe Fractal” artworks exploring nature as a force of destruction, dispersal, and renewal in the Caribbean’s ongoing dialogue with climate change and ties to diaspora alongside Santos-Febres’ understanding of Caribbean fractality as a decolonial feminist imperative that sees transformative interconnectedness across structural, personal, spiritual or community levels demanded a radical turn. Electric Marronage served as a mediator to a world outside of the MoMA where we are unbound by the imperial nostalgia that demands capture and display.11

Electric Marronage, as digital current, traverses the physicality of the museum. The fractals are in conversation with Ballester Panelli’s extensive training, beginning from his childhood experiences at the age of eight where he playfully emulated his father’s photographic techniques in el campo to selftraining practices garnered through local artists and galleries (Ballester Panelli

2020). One practice in his self-training has remained a constant throughout the years and it’s centering quotidian items, paying close attention to the details and components that culminate in the essence of an item, always gauging the inner workings that are often taken for granted, but that ultimately inform ways of being. In “Caribe Fractal,” Ballester Panelli emphasizes the need to remain attentive to the smaller details found within the everyday (Ballester Panelli 2020). Looking for the patterns within the fractals that comprise “Caribe Fractal” forces audiences to explore larger signi cations and implications found within daily realities. When installed, the twelve acrylic panels, “Tierra” (18"×18"×18") and “Mercado” (36"×36"×36"), create a multilayered fractal work (See Figure 1 “Agua,” “Mercado,” and “Tierra”). “Tierra” and “Mercado” gesture to this practice of engaging with the quotidian, each of the twelve panels present a different photographic image which has been digitally enhanced and altered.

“Tierra,” for example, consists of six close-up images of vegetation native to Puerto Rico. These images are then recon gured as geometric patterns where the audience is forced to pay particular attention to the same image through a range of vantage points. Panels centering on the vegetation demand that those who are not natives to the area bear witness to an integral part of Puerto Rico’s ecosystems and expound on conversation dealing with disasters such as Hurricane María. Both “Tierra” and “Mercado” utilize the layering of panels, when positioned against light, the panels become translucent to the point that the six panels don’t solely have individual meaning but must be read in unison. Fractality here becomes porous with meaning, demanding that the audience make do with narratives of presumed fragmentation and ensuing un/cohesiveness. “Mercado” adds to the interpretation by foregrounding a scale as its front panel which poses questions on a deliberate tactic of balance, weight, surveillance, and mobility.

Additional fractals such as “Mariwo,” a 6'×6' photo on polyester (See Figure 2 “Mariwo”), demonstrates a mix of geometric patterns in various shades of green. Mariwo or mariô refers to the stalk of a dry palm leaf, its spiritual uses serve in the protection of spaces from negative energy and separator between worlds.12 Upon closer inspection, one can note that it is not a singular image, but that similarly to “Tierra” and “Mercado,” the original photograph has been digitally cropped and posed through various angles that mirror each other. The geometric patterns that surface demand that audiences remain attentive to a singular structure of the image through various angles, all while being aware that what is captured within the frame of the polyester does not depict the full scope of the mariwo –one must explore beyond the frame. Audiences are forced to simultaneously grapple with and maneuver between the visual and material implications of “Mariwo.” In the wake of disasters, we must contend with the survival of the Mariwo and the survival of the Puerto Rican diaspora in connection to the Caribbean and the world at large. “Tierra” exempli es fractality as a unison of forces meant to be categorized as opposite of each other, but that

complement each other and craft relations. “Mercado” adds to the conversation on fractality by gesturing towards practice, that is, the ability or inability of its audience to balance along the scales. “Mariwo” leaves the message clear, survival is fractal.

Fractal 4: Art in Pandemic Times

In the fall of 2020 Electric Marronage turned towards maroon logics and built on the lessons from the organizers and artists in Puerto Rico that have formulated auto-gestion and grassroots projects to bregar, or problem solve on the ground within colonial imperial contexts. At the university we engaged the digital when support diminished for our project, we utilized telecommunication

Figure 2. José Arturo Ballester Panelli, “Mariwo,” Caribe Fractal, 2019.

systems such as Zoom provided by the university to host a reception and curated a digital exhibition for “Caribe Fractal.” Following Electric Marronage’s rules of fugitivity: escaping, stealing, feeling, and whatever, proved crucial during the pandemic as we posed questions regarding dissemination and accessibility within the digital realm: “The digital—doing digital work—has created and facilitated insurgent and maroon knowledge creation within the ivory tower. It’s imperfect and it’s problematic—and we are all imperfect and problematic. But in that sense, I think the digital humanities, or doing digital work period, has helped people create maroon—free, black, liberatory, radical—spaces in the academy” (Dinsman 2016). Electric Marronage took on the digital, despite the boundaries and limitations. Centering “Caribe Fractal” provided both method and praxis within the digital realm, one that was in direct conversation with histories of dispossession globally. Fractals reminded us that geographies are not fragmented as the cartographies of modernity would like us to believe. Rather, like fractals, spaces and people collide. Through Electric Marronage’s rules of fugitivity, “Caribe Fractal” propelled itself as a counter to the digital which is sustained out of traditional notions grounded on binaries and codes. Fractals within the digital realm embedded the saliency of relations. The digital as a limited technology that has barriers to entry and is imperfect as a democratic platform, became a site of escape sustained through relations (Risam 2018). After the closure of the MSU Museum, Electric Marronage sought support from MSU’s Residential College in the Arts and Humanities (RCAH) LookOut! Gallery which showcases a compelling array of exhibits and programs centered on visiting and local artists, students, and community groups. In collaboration with the LookOut! Gallery, and its then director of exhibition spaces Tessa Paneth Polak and preparator Steven Baibak, we began to execute the material and digital exhibit. Not only were arrangements for the transportation of additional works made through these digital platforms, but without Ballester Panelli on campus to physically curate these items, calls were made to gather information on the signi cance of pieces and their placement. Once the pieces arrived at the gallery and were displayed, we contracted AbleEyes™, a platform for providing “visual, state of the art experiences/teaching tools to children and adults with disabilities.” Through AbleEyes™’ technology the visuals of “Caribe Fractal” were reproduced and uploaded to digital realm making the exhibit accessible for those with disabilities as well as those under stay-at-home orders worldwide.13 The digital exhibitions allowed individuals access to the art, the ability to shared experiences online, and build community. Audiences were able to make their way throughout the gallery while viewing Ballester Panelli’s work from any vantage point, even able to zoom in and receive a close-up of immaculate details. We then prepared a digital exhibit to accompany “Caribe Fractal” on the Electric Marronage website. This included a video interview with Ballester Panelli overlayed with fractal images as well as images that conjured

Figure 3. José Arturo Ballester Panelli, “Caribbean Flaming June,” En tiempos de pandemia, 2020.

the Afro-syncretic practice of Santería through images of plants, land, botanicas, and other sacred ephemera. Together, the digital exhibits from the LookOut! Gallery and the Electric Marronage website sutured two distinct and inextricable aspects of Caribbean fractality: ecology and the sacred.

In the six months that had passed since the pandemic had locked down cities, campuses, and nations, Ballester Panelli added other important elements to the exhibits, a project called “En tiempos de pandemia” (In Pandemic Times) which offered never before seen video footage of a Puerto Rico amid the pandemic. He utilized a camera drone to navigate various streets and shorelines focusing on populations that remained houseless, a critique on both the devastating aftermath of Hurricane María, the inept governmental response to the pandemic, and continual ood of tourism that brought with it a rise of COVID-19 cases.

As part of “En tiempos de pandemia,” Ballester Panelli worked with family and community members to prepare meals for those who were unhoused, what he called “fuera de la burbuja” (outside of the bubble). In doing so, he aimed to shed light on the way that those suffering with substance misuse, mental illness, and poverty were left outside of the relative safety of a home. In addition to preparing daily meals, Ballester Panelli engaged folks in conversation and saw them as valued and valuable community members and subjects for his art. He insisted that this sector of the community deserved faithful witnesses and, in his work, he made those usually the recipients of abject neglect into ethereal gures.14

The image “Caribbean Flaming June,” for example, is a photo of a houseless woman in Santurce, PR sleeping in a vestibule and wrapped in a sheet [See Figure 3 “Caribbean Flaming June”]. Ballester Panelli blurred the image forcing the viewer to look closer, to gaze upon the subject, and to focus on the survival of those living outside the safety of a home during a pandemic. Moreover, we see this “Caribbean Flaming June” image superimposed on a fractal image of the sea and she is surrounded with feathers, denoting ecology, the celestial, the sea, and adornment. This image, when rst exhibited, was printed onto a twin-size mattress, and leaned on the gallery wall, offering the viewer a way to contend with the layered signi cance of the materiality of the mattress and the visuality of attending to those who are most invisibilized, ignored, and devalued. Together “Tierra,” “Mercado,” “Mariwo,” and “Caribbean Flaming June” requires us to make do with histories of fractality, to learn from everyday surroundings and people by making connections that would otherwise be lost.

Fractal 5: Decolonial Feminisms, Reimagining Worlds/Otherwise

Decolonial feminisms, is an anchoring point for our work in organizing, curating, and coordinating transnational, hemispheric, and digital projects that

imagine beyond the limits and con nements of universities and institutions. While there are multiple and complex genealogies to decolonial thought and decolonial feminisms (Indigenous, Black, Caribbean, Chicana, Latin American, etc.), we nd it fruitful to see the linkages in how these political imperatives and intellectual traditions help us navigate and disentangle the matrices of Western and white supremacist understandings of being, knowing, humanity, and ecology, and arts practices. Our drive to create spaces for visual and other arts to thrive, is propelled by decolonial feminist ways of knowing and methods of subverting and expanding the cracks in the ongoing colonial projects that seek to invalidate the practices, arts, language, and knowledge of communities it deems as Anthropos, noncivilized, and fungible (Nishitani 2006). Decolonial feminist practices, ethics, and politics, thus, informs our work within and across community spaces and sustains us as we strike new paths that traverse hostile institutions, norms, and structures.

In the document “Framework and Terms for Struggle” produced by StrikeMOMA Working Group to guide those interested in learning or organizing, they state, “There is no blueprint for dismantling MoMA, but here is the starting point: whatever comes after MoMA, it must preserve and enhance the jobs of museum workers and enact reparative measures for communities harmed by the museum over time, beginning with the legacy of land dispossession. The agenda is open, but any path forward must be premised on the acknowledgement of debts owed: from top to bottom and horizontally too, between and within groups, communities, and movements.” “Caribe Fractal” as one of many points of departure across the digital realm envisioned and practiced by Electric Marronage allows us to contend with Strike MoMA’s call. “Caribe Fractal” as Electric Marronage’s rst exhibition held within the parameters of the land grab institution that is MSU was met with numerous hurdles that at the same time offered us room to imagine worlds/otherwise. Turning to the digital realm, with all its imperfections and barriers, crafted an agenda in conversation with Strike MoMA’s call to acknowledge the “debts owed” as individuals working within and outside of institutions that remain unaccountable.

Electric Marronage is not rid of critique. Electric Marronage is by no means an end. Electric Marronage is not the only way. What Electric Marronage does is pave another road for us to reimagine worlds, to build towards the future, to maintain hope and it works for the time being. Perhaps years from now Electric Marronage may cease to exist, possibly shifting into something anew or sunsetting altogether, but from it there will always be a group of women of color and the digital kinship that they created throughout talks, workshops, blogs, and curations which will remain ever-envisioning the worlds/otherwise we need.

Stephany Bravo is a dual doctoral candidate in English and Chicano/Latino Studies at Michigan State University. Her transdisciplinary research documents how

BI&POC in present-day Compton, California account for their lived realities through poetry, murals, archives and other ephemera. Stephany serves as the Project Manager for the Open Boat Lab which mediates curation, storytelling, and community organizing development in the Diaspora Solidarities Lab.

Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vásquez is an Afro-Puerto Rican writer, teacher, and scholar from Hoboken, NJ. She is Associate Professor of English at Michigan State University and the author of Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (Northwestern, 2020) and the forthcoming The Survival of a People (Duke University Press). Her published work can be found in Hypatia, Decolonization, CENTRO, Small Axe, Frontiers, Hispano lia, Contemporânea, Post 45 Contemporaries, SX Salon, and other scholarly journals and public forums. She is a founder of the MSU Womxn of Color Initiative, #ProyectoPalabrasPR, the Mentoring Underrepresented Students in English recruitment program (MUSE), and the DH project Electric Marronage. Dr. Figueroa is a 2015–2017 Duke University SITPA Fellow, a 2017–2018 Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, a 2021–2022 Cornell University Society for the Humanities Fellow and the PI of the Mellon Diaspora Solidarities Lab (www.dslprojects.org).

Notes

1. Phase one laid the groundwork for phase two where a spokescouncil-based convening determined the shape, steps, and mechanics of a just transition to a postMoMA future that prioritized its workers and communities. See StrikeMOMA Working Group. “Framework and Terms for Struggle.” StrikeMOMA Working Group of the International Imagination of Anti-National Anti-Imperialist Feelings (IIAAF). Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.strikemoma.org/.

2. [Taller] Electric Marronage. “About.” Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www .electricmarronage.com/

3. We do not understand African-descended peoples and Indigenous peoples as mutually exclusive groups. We recognize and af rm Indigenous sovereignty, the rights of Indigenous African peoples, and the lives and legacies of Afro-Indigenous-descended peoples.

4. Electricians refers to the group of individuals behind Electric Marronage, they also refer to themselves as kin.

5. Electric Marronage takes its heed from within the matrix of histories of maroonage and cimarronaje across the Caribbean and the Americas. The word marrón is derived from the “New World” Spanish word “cimarrón” which was rst used to describe livestock that had escaped into the hills, or cimas, in Caribbean colonies. Marronage includes distinct and interrelated histories of Black and Indigenous ight from colonial and settler plantations in both temporary and permanent instantiations (petit and grand marronage). In some cases, permanent secluded communities were created such as Palenques and Quilombos (Brazil and Colombia) and in all cases maroons were disruptive of colonial and imperial projects that sought to make subjects and slaves out

of Africans and Afrlo-Indigenous peoples. While the histories of palenques, quilombos, and marronage is fraught with both internal and external tensions, the acts of marronage are rooted in forms of self-determination, liberation, and providing protection, resources, and sustenance for one’s chosen communities. Attending to practices of marronage likewise allows us to attend to logics of worlds/otherwise, that counter the limited and limiting worldviews of the modern/colonial enterprise and instead attend to alternative practices and desires rooted in decolonizing and liberatory ways of being and knowing that extend through interrelationality and reciprocity.

6. Taller is one Spanish word for workshop. In Puerto Rico and its diaspora, a taller can range from an artist or community space to an auto repair or teaching space. Talleres are inherently collaborative and community oriented and have been used as a way to denote insurgent spaces as well as grassroots efforts. The founders of [Taller] Electric Marronage, both Black Puerto Rican feminists, take up the term taller as a way to open up possibilities of collaboration beyond the academy and in relation to local, hemispheric, and transnational communities to which they are accountable.

7. José Arturo Ballester Panelli is an Afro-Caribbean artist based in Puerto Rico. His work explores the ties between photography, Afro Caribbean aesthetics, history, and the racial, social and ecological systems in the Caribbean and its diasporas.

8. Caribe Fractal is one of many curations, workshops, and dialogues curated through Electric Marronage that attend to insurgent decolonial and Black feminist politics, practices, and ethical imperatives.

9. “Fractals” are a method that are also part of what adrienne maree brown calls “emergent strategy” of organizing along the grain of Black feminist speculative praxis and entails understanding how “complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions.” See: brown, adrienne maree. “Fractals.” Accessed February 21, 2022. http://adriennemareebrown.net/tag/fractal/.

10. #ProyectoPalabrasPR (#PPPR) is a “radical hurricane recovery project” in partnership with Salon Literario Festival de la Palabra. Immediately after Hurricane María, a women of color collective emerged on the island and worked alongside diaspora with the intention to serve as a collaborating partner after disaster, their efforts ranged, but were not limited to the areas of fundraising and documentation through testimonio.

11. Rosaldo, Renato. Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993).

12. Rodriguez, Claudia. “¿Qué es el Mariwo? El que separa los mundos espirituales.” Ashé. https://ashepamicuba.com/mariwo-santeria/. Accessed January 17, 2023

13. AbleEyes provides a user-friendly platform to teach skills and explore environments from several different perspectives. It is designed with disabled users in mind, including wheelchair users, those with autism, ADHD, the elderly, victims of trauma, those with anxiety, the hearing impaired, and those with post-traumatic stress disorder. It is also local to the Greater Lansing area, allowing us to work closely with and be accountable to a community-based organization in our area. See: Able Eyes. “Mission Statement.” Accessed December 10, 2021 https://www.ableeyes.org/

14. Ballester Panelli’s twenty plus years of work as an artist, designer, and teacher is personal and political. Having lost his job and home after Hurricane María in 2017, he went to the neighboring island of St. John and helped with rebuilding efforts. In doing so he recentered himself within his lived experience growing up in the mountains

Stephany Bravo and Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vásquez · 45

of Adjuntas and his positionality as a “jibaro” (i.e.- man of the mountains in Taino language) an act that helped him reconceptualize his art and life as countering colonialisms claim to death and destruction. Ballester Panelli, José Arturo. “Ballesta 9.”

Accessed December 10, 2021. http://www.ballesta9.com/.

References

Able Eyes. “Mission Statement.” Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.ableeyes.org/.

Ballester Panelli, José Arturo. “Ballesta 9.” Accessed December 10, 2021. http://www .ballesta9.com/.

Ballester Panelli, José Arturo. “Caribe Fractal, Fractal Caribbean.” Residential College in the Arts and Humanities (RCAH) at Michigan State University, LookOut! Gallery. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://rcah.msu.edu/uniquely-rcah/lookout /Ballester-2020-Exhibit.html.

Ballester Panelli, José Arturo. 2020. “José Arturo Ballester Panelli Entrevista.” By Maya Santos-Febres, Sept. 28, 2020, video, 12:26, https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=InlPJxmTbQQ.

brown, adrienne maree. “Fractals.” Accessed February 21, 2022. http://adriennemaree brown.net/tag/fractal/

Christian, Barbara. 1987. “The Race for Theory.” Cultural Critique (6): 51– 63. https:// doi.org /10 2307/1354255

Dinsman, Melissa. 2016. “The Digital in the Humanities: An Interview with Jessica Johnson,” Los Angeles Review of Books, July 23, 2016, https://lareviewof books.org /article/digital-humanities-interview-jessica-marie-johnson/

Dotson, Kristie. 2016. “Between Rocks and Hard Places: Introducing Black Feminist Professional Philosophy.” The Black Scholar 46 (2): 46 –56

Figueroa-Vásquez, Yomaira C. 2020 Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of AfroAtlantic Literature. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. New York: Crossing Press. Miner, Dylan. “Home.” American Indian and Indigenous Studies. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://aiis.msu.edu/about/history/.

Nishitani, Osamu. 2006. “Anthropos and Humanitas: Two Western Concepts of ‘Human Being.’ ” Translation, Biopolitics, Colonial Difference, 259 –273.

Pérez, Laura E. 2010. “Enrique Dussel’s Etica de la liberación, U.S. Women of Color Decolonizing Practices, and Coalitionary Politics amidst Difference.” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 18 (2): 121–146.

RCAH LookOut Gallery. “Creativity Lives Here.” Accessed December 10, 2021. https:// rcah.msu.edu/uniquely-rcah/lookout/index%20NOT%20USED.html.

Risam, Roopika. 2018. New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy. Northwestern University Press.

Rosaldo, Renato. 1993. Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press.

Santos Febres, Mayra. 2019. “Contemporary Caribbean Fractality and Racial Ecosystems: A Native Perspective.” Womxn of Color Initiatives Keynote Address. Michigan State University.

StrikeMOMA Working Group. n.d.-a “A Conversation with Kency Cornejo, Saudi

García, Macarena Gómez-Barris, Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Mónica Ramón Rios”

Accessed February 16, 2021, https://youtu.be/a4HNvsf8XEs

StrikeMOMA Working Group. n.d.-b “Framework and Terms for Struggle.” StrikeMOMA Working Group of the International Imagination of Anti-National Anti-Imperialist Feelings (IIAAF). Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.strikemoma.org/. [Taller] Electric Marronage. “Home.” Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.electric marronage.com/