8 minute read

The Latest on (ugh) Jumping Worms

Small but formidable garden pests, these escape artists continue to elude researchers.

STORY AND PHOTOS GAIL HUDSON

One of the newest pests to haunt northern gardeners, jumping worms (Amynthas agrestis) wiggle and slither like tiny snakes in the top 2 or 3 inches of soil. They like it cool, moist and shady, ideally in mulched beds and any other “places where the soil never goes above 85 degrees Fahrenheit,” says Lee Frelich, director of the Center for Forest Ecology at the University of Minnesota. “And that’s not very hot.”

Why you might find more worms in one place than another is just the beginning of what researchers like Frelich have learned as they studied the behavior and biology of these invasive species over the past 18 years. Armed with field research conducted during the summer of 2024 and years past, Minnesota’s experts hope to jumpstart the search for answers to the big question worrying gardeners and green industry professionals: How can we deal with jumping worms once they appear?

For now, prevention (not bringing jumping worms into your garden in the first place) remains the only viable solution for gardeners. Thanks to a handful of studies by U of M researchers, new management tools may be on the horizon.

The invasion and impact

“A single [jumping] worm, and potentially a single cocoon or egg, is all it takes to start a new infestation,” writes James Calkins, regulatory affairs manager for the Minnesota Nursery and Landscape Association (MNLA). What’s even scarier is the impact these small pests can have. Jumping worms have been reported and confirmed in Minnesota counties from St. Cloud to Rochester, as well as Madison, Milwaukee and Green Bay, Wisconsin, and central and eastern Iowa.

Jumping worms can damage the roots and even kill plants; they make soils easier to erode, inhibit the establishment of seedlings and regeneration of native plants; they damage critical connections between soil fungi and plants, and experts believe the worms may stop soil from absorbing and holding water.

From home gardens to nurseries to forests, officials at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) warn this invasive species may cause recreational, economic and ecological damage. In July 2024, the agency declared jumping worms (Amynthas and Metaphire species) a prohibited invasive species in the state. That means it is unlawful (a misdemeanor) to possess, transport, purchase or introduce jumping worms without a permit. (For people who unintentionally have the pesky creatures on their property, no permit is necessary.)

What can a gardener do?

That’s exactly what Integrated Pest Management Specialist Erin Buchholz and Frelich have been attempting to figure out at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum. For three years, researchers conducted field trials in a wooded area, testing seven different treatments to eradicate the worms.

The study concluded in the fall, and Buchholz says she expects the numerical data to show no cure-all for jumping worms. At first glance, Buchholz says none of the treatments were 100 percent effective. “I tried to use more horticulturally accepted practices like sulfur or diatomaceous earth or fertilizer—stuff that you are going to be using in your garden anyway,” she says. “Each treatment had at least one worm [remaining] in one replicated plot.”

Some preliminary observations? Buchholz found fewer jumping worms and/or European nightcrawlers (Lumbricus sp.) after treatment with tea seed meal fertilizer which is high in saponins, a soap that injures their skin, and where researchers had removed leaves on the ground (a preferred food source for worms). The fertilizer is currently used to destroy earthworms on golf course greens. Buchholz says dusting a plot area with diatomaceous earth or the native, beneficial fungus in BotaniGard ES insecticide had moderate or noticeable effect.

A closer look at containers

What about jumping worms found in the soil of a pot? “Horticulture, unfortunately, is one of the main vectors for their spread,” says Brandon Miller, an assistant horticulture professor at the U. For example, whenever a landscaper unknowingly moves a plant from infested soil or a nursery unintentionally brings shipments of plants with jumping worms into Minnesota, he says they help the worms invade more gardens and even wilderness areas.

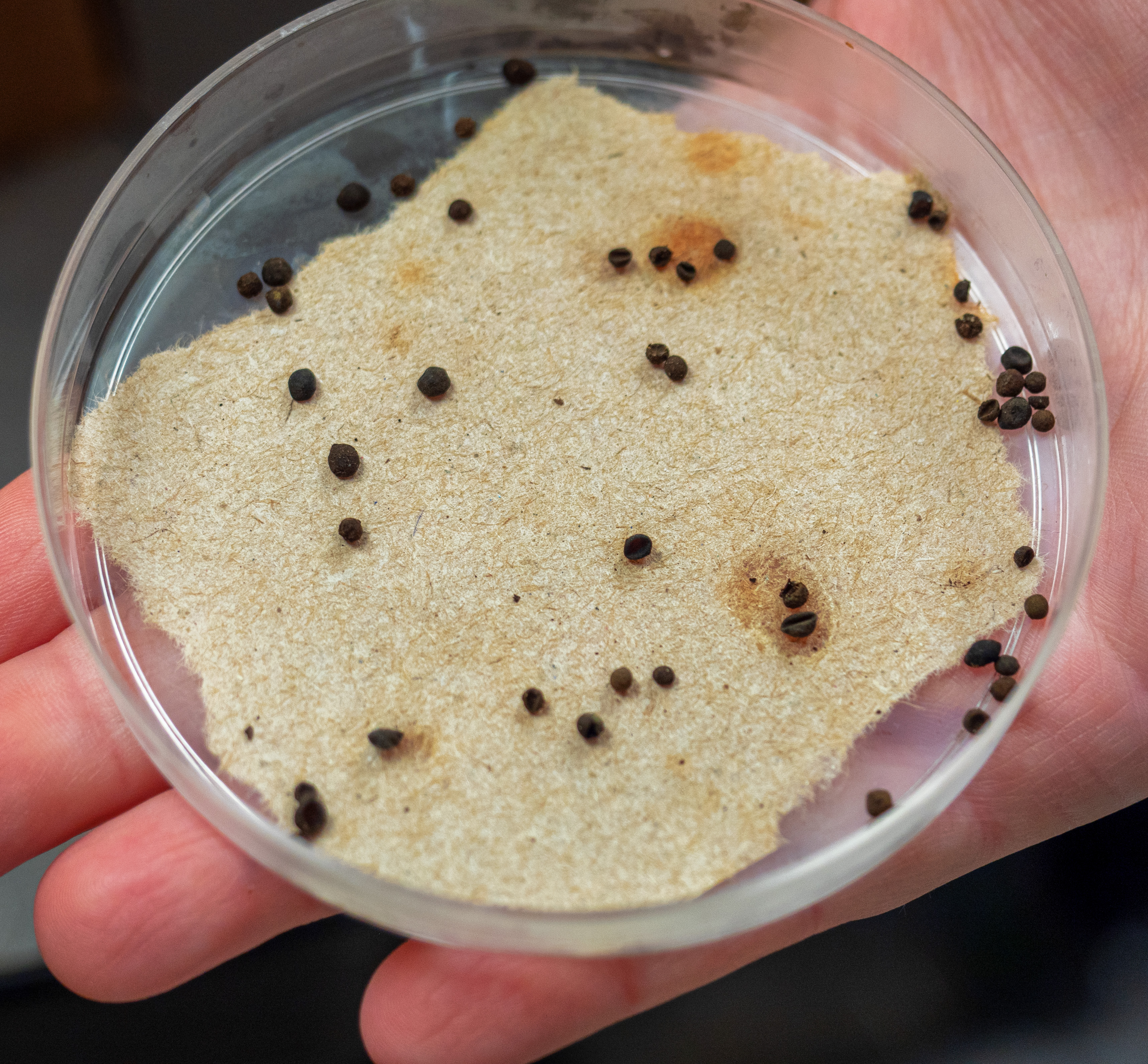

But Miller says a new study, initiated by graduate researcher Jenna Simon, is already showing surprising results. Eight different chemicals were applied to a soil media mix in 90 pots containing sugar maple saplings and six jumping worms each. The treatments included several insecticides, a fungicide, a fertilizer and a slug repellent. Currently, unless the product label provides clear approval, using these chemicals to kill jumping worms is illegal as it could have ecological impacts. The containers were zipped tight in mesh laundry bags to prevent the worms, which Miller calls “escape artists,” from getting away.

After four weeks, students sifted through the soil to count how many worms were left. “Two of them are effective and we’ll have more certainty by next spring,” says Miller. But he reminds gardeners that the results will be only applicable for plants in containers, not plants in the ground.

Examining erosion

As jumping worms munch their way through mulch, compost and leaves, they excrete poop that resembles loose coffee grounds, causing a change in the soil structure. Researchers want to measure what happens because they believe the worms’ impact could be devastating to forests, affecting their long-term sustainability.

“The first time that we thought about erosion was when we were walking on a steep slope of a jumping worm-infested forest,” says Kyungsoo Yoo, a soil scientist at the U. “We found the ground was so unstable… everything was sliding down when you stepped on it.”

Yoo and his students are working at the Arboretum, too, taking measurements with erosion pins and sediment collectors to see how much erosion occurs, particularly after strong storms. Another erosion study is happening in southeastern Minnesota with the help of volunteers. Both results won’t be ready until 2025.

A race for more research

Since jumping worms are extremely attracted to mulch, Miller’s students are also testing whether infested bagged mulch can be solarized or heated up to kill the worms and their eggs. Another study by entomologist Vera Krischik is designed to develop the safest and most effective integrated pest management strategies to control jumping worms without impacting beneficial insects.

Making peace with the worms

Until we have answers, can we live with these pests? Frelich tends a jumping-worm infested woodland garden next to his downtown Minneapolis condo. He was the first to discover the worms in Minnesota in nearby Loring Park. Since then, he’s decided to accept them. “If you have a flat site and you don’t have a lot of foot traffic, you can get along with jumping worms,” he says.

Best Practices

The Minnesota Nursery and Landscape Association reports jumping worms have been found in compost, organic landscape mulches, container-grown nursery plants, yard waste and landscape soils. To minimize spread:

Be careful when sharing and moving plants. Know where they came from and look for jumping worms.

Do not store mulch on the ground or purchase mulch in bags with holes. Look for a supplier that heat treats compost to 131 degrees F for at least three days.

Don’t buy or use jumping worms for composting or bait.

Dispose of worms in the trash, not in your compost or yard waste site.

Water less in established garden beds. Jumping worm populations at Arboretum test sites plummeted during the drought in 2022 and 2023 but did not decline in irrigated areas.

If your beds are heavily infested, do not add mulch (a food source). This includes wood chips, cocoa bean hulls, shredded coconut, leaves, compost and pine needles.

Clean all garden tools and footwear when moving from one area to another.

Remember, it’s illegal to use a product for a pest that’s not included on its label.

Do You Have Jumping Worms?

Not having jumping worms in the first place is the best way to prevent them. Learn how to identify them at northerngardener.org/jumping-worm-id

Funding for this research was provided by the Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pests Center at the University of Minnesota, which is supported by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources.