5 minute read

SCOTUS Decision Significant for WOTUS

NMED seeks surface water permitting program in its place

A recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court is no drop in the bucket for farmers and ranchers who have struggled for more than 50 years to navigate the regulatory landscape created by the Clean Water Act and “water of the United States,” commonly referred to as WOTUS. The Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency decision is a win for farmers and ranchers.

Since its inception, the ambiguity, specifically of the term “waters of the United States,” has plagued stakeholders of the Clean Water Act. The term was included, but not defined, by Congress in 1972 when they expanded the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 into what would be commonly known as the Clean Water Act. Congress passed the Clean Water Act against the backdrop of a broader focus on the environment as the nation saw the Cuyahoga River Fire in Ohio in 1969 and the establishment of the EPA and the first Earth Day in 1970.

While Congress outlined a goal of restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of our nation’s waters by regulating discharges of pollutants from a point source into a navigable water, they failed to provide much direction beyond that.

“It’s been left to the EPA and the [Army] Corps [of Engineers] since then, and the courts to some degree because there’s been a lot of litigation, to figure out where the scope of the Clean Water Act is,” said Courtney Briggs, Senior Director of Government Affairs for the American Farm Bureau Federation. “That’s why it’s been such a long, ongoing fight.”

By defining, in their own way through rulemaking, what qualifies as a WOTUS, each administration has adjusted the scope of the Clean Water Act. Briggs, who at the time was with a different industry segment, remarked on the “Ditch the Rule” campaign farmers launched in response to their displeasure to the Obama administration’s attempt to define WOTUS. The Trump administration provided its own narrowed definition through the Navigable Waters Protection Rule before the Biden administration came in and proposed a much broader definition in the rule finalized in January of 2023. It’s a “lack of clarity” that defines the ongoing issues, because everyone, farmers included, wants clean water, said Briggs.

The process triggered by a WOTUS designation is one reason farmers and ranchers struggle with the varying broad definitions. The need to obtain a Clean Water Act permit can set off an “avalanche” of other federal statutes a landowner has to comply with and result in a “very long and drawn out” permitting process, said Briggs. Under the Biden administration’s 2023 rule, land features that have the ability to hold water after a rainfall, such as a low spot in a farm field, could be regulated as a WOTUS and subject to the resulting federal permitting process.

“It really does come down to a land rights issue,” said Briggs. “Over the last 50 years, there’s been this regulatory creep that has happened where we’re no longer regulating waters that are wet, we’re now regulating dry land. That’s why we are so invested in this issue.”

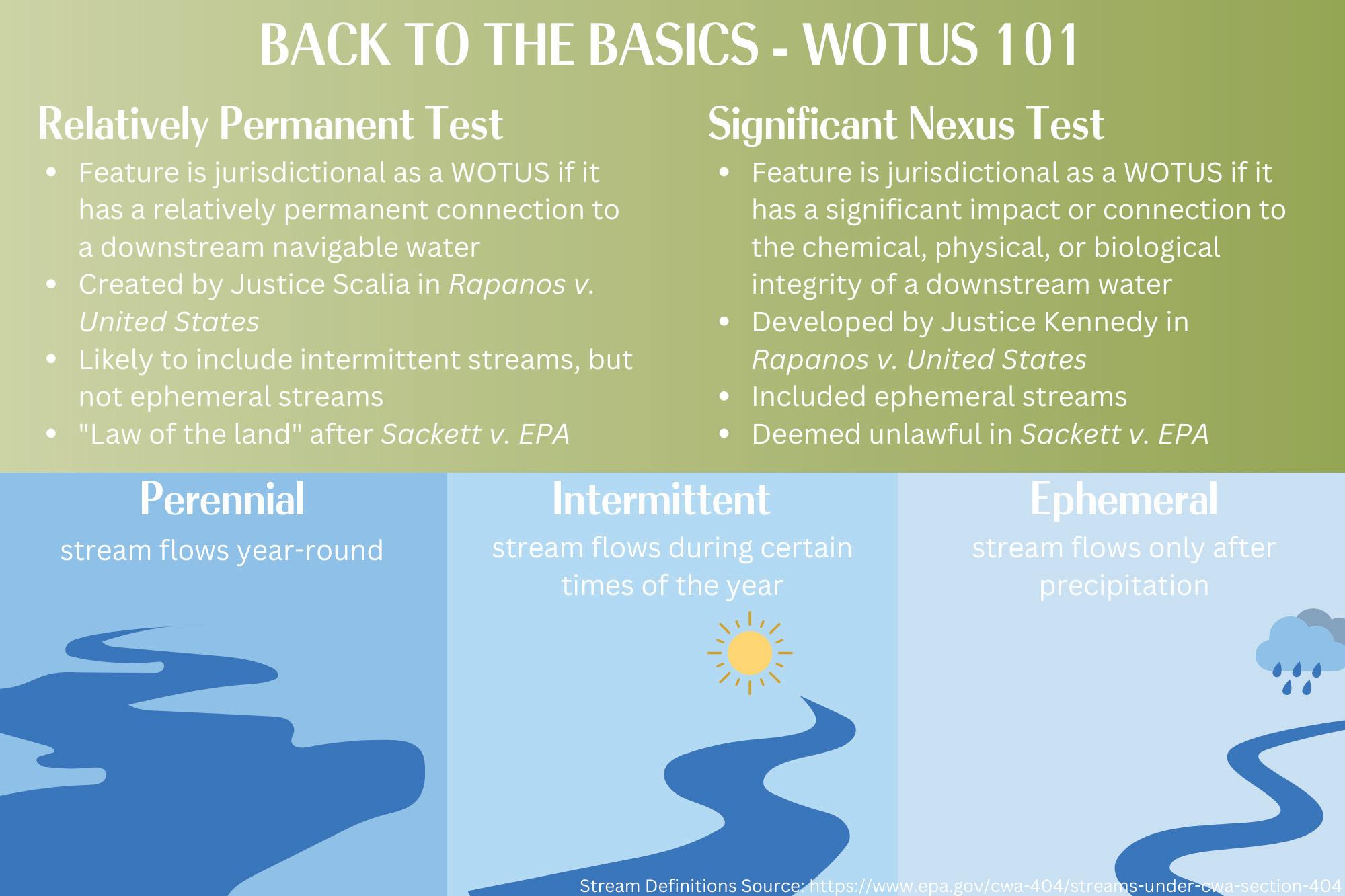

Enter the recent decision by the Supreme Court on Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency. In a 9-0 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the method the EPA had used to determine their jurisdiction over the Sackett’s land was wrong. This method, called the Significant Nexus test, was developed by Justice Kennedy in the Supreme Court’s Rapanos v. United States decision, and states that if a feature on the land has a significant impact or connection to the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of a downstream water, the EPA can regulate it as a WOTUS. The ambiguity of what “significant” means left landowners, especially in the southwest where there are many land features that have the ability to hold water after a rainfall, confused about how to proceed.

“It’s such a subjective test, and you’re beholden to whatever Corps official is assigned to you, whatever their opinion is, is going to be the decision that is made,” said Briggs. “You have little recourse as a landowner to appeal that decision, unless you want to dedicate your life to trying to appeal this and spend all of your resources doing that.”

The elimination of the Significant Nexus test through the Sackett case is ultimately a win for farmers and ranchers across the nation seeking clarity on their working lands, but New Mexico farmers and ranchers aren’t in the clear yet. States can regulate their own waters, and New Mexico regulators are looking to fill the perceived gap left by the Supreme Court’s decision through a surface water permitting system.

“In New Mexico, it is difficult for us because the vast majority of water courses we have are ephemeral,” said Director of the Water Protection Division for the NM Environment Department John Rhoderick during a meeting of the Water and Natural Resources legislative interim committee. “They are not continuous running yet if not protected they have the potential to have significant impact. That’s why we are looking at a surface water permitting system.”

NMED is planning an “incremental” rulemaking that will bring New Mexico’s surface water discharge permitting under the direction of the state with a goal of having a framework to present to the Water Quality Control Commission by 2025 and a functioning permitting program by 2027, said Rhoderick. The process will include public outreach to inform how NMED moves forward, said Rhoderick.

New Mexico currently has 3,955 permittees under the federal National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), which include 121 individual discharges from cities or large facilities like an Airforce base, 23 Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), and more than 3,600 stormwater discharges from municipalities, construction sites, and others, said Rhoderick.

“There won’t be substantial changes to what’s required under their [NPDES] permits at this point, if their compliant,” said Rhoderick. “The biggest impacts are going to be on our ability to protect dry water courses, the ephemeral streams, to deal with some of our dairies and things like that as they move forward.”

New Mexico’s surface water permitting program will have to meet requirements at least equal to those already in place by the federal government, but the state has the ability to make the requirements more stringent. NMED will need an estimated 30 additional staff members and recurring funds of $6 million or more per year to take on the permitting load once fully operational, said Rhoderick. The intent is to have the permitting program partially or fully fund itself through permit fees, said Rhoderick. NMED does offer dairies, for example, the ability to pay current permitting fees over a period of several years, said Rhoderick.

“Our intent is not to create any type of hardship for industry of any type, but it is to ensure that we are protecting not only the surface water, but the ground water, for the citizens of the state of New Mexico,” said Rhoderick.

The WOTUS debate is far from over. With the Significant Nexus test off the table after the Sackett case, the federal agencies will now turn to the Relatively Permanent test established by Justice Scalia in the Rapanos v. United States case. The Biden administration’s 2023 rule is still in effect but challenged in three district courts and stayed in half of the states. The 2023 rule still needs to adjudicated, and AFBF is asking the court vacate the rule following the Sackett case, said Briggs.

“Our objective has always been to find a definition and scope of WOTUS that adheres to congressional intent, that respects Supreme Court precedent, and that respects the role states in protecting our nation’s waters,” said Briggs.