47 minute read

Introduction: _Rolling Hills of Mendip no longer roll

// Introduction

// Figure 06: Author’s image, Whatley Quarry. The view looking west, taken with a drone. December 2018.

Advertisement

_Rolling Hills of the Mendips no longer roll_

A short history of extraction in the Mendip Hills.

“A small hill at Vobster has disappeared. Larger hills at Sandford, Milton and Dulcote, featuring prominently in the setting of the Winscombe Valley and the city of Wells, have lost up to two-thirds of their substance. [...] Torr Quarry near Frome is totally remodelling half a square mile of countryside; the vast hole is surrounded by towering ‘environmental banks’ that hide it from the view”.1

This extract is taken from a record of proceedings of a seminar held on October 23, 1993, to examine the issue of limestone extraction facing the Mendip Hills. The seminar was organised by The Royal Bath & West of England Society and The Royal Geographical Society and was titled, ‘The Mendip Quarries, A Conflict of Interests.’2 The seminar took place 27 years ago with local residents expressing their concerns for the environment, due to the levels of extraction unfolding in the Mendip Hills.

I was first struck by the overwhelming scale of the extraction of resources on a walk near my family home a decade ago. I remember asking my mother how Whatley Limestone Quarry in Somerset had been formed, assuming it was a ‘natural’ phenomenon. She turned and told me humans had made it. It struck me that humans were capable of overwhelming changes to a landscape—Whatley Quarry can be seen from the moon—making it appear ‘wild’, while concealing, and continuing, the harmful effects of mass industrial activity. Elon Musk, the SpaceX entrepreneur, has publicly declared that humanity needs to have a backup Earth, suggesting it should be located on Mars. To do this would require the terraforming of Mars—even if terra means Earth. We are, however, already terraforming our planet, shaping it through direct and indirect responses to the demands of financial markets: every year, between 60 to 100 billion tonnes of material is extracted from the Earth.3 In the documentary Banking Nature, Pablo Solon explains that while human beings have occupied Earth for hundreds of thousands of years, it is only in the last 150 years that we have

1

2 Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993).p.31. Ibid.

National Limestone Reserves in the UK

The Mendip Hills

// Figure 07: Author’s diagram. National limestone reserves in the UK with the Mendip Hills limestone highlighted. Due to its location it is an important building resource for the south of the UK.

seen the Earth show distressing signs of change. Solon argues that “it isn’t human beings that are destroying nature, but rather the economic system.”4 Carboniferous limestone of the Mendip Hills was fundamental to the building of cities in the UK such as Bristol, Bath and London. It is now being extracted on a colossal scale to reach national requirements, for limestone is an indispensable mineral for the production of cement, a fundamental material for the construction industry. Cement production is also one of the largest producers of greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide.

The scale of extraction at the Mendip Hills accounts for 21% of total national extraction.5 There are 22 quarries within the Hills today, 11 of which are active and the rest either disused or “mothballed” (i.e. inactive).6 The value of this area for its mineral resources comes from the lower Carboniferous limestone.7

It was formed 359 to 327 million years ago when the “arid terrestrial environment of the Devonian gave way to shallow marine conditions” forming four distinct types of limestone—and giving the Mendip Hills their unique features and proving an ideal location for mineral extraction.8 In addition to the created environmental banks, the gently rolling hills provide a perfect shield to hide the quarries from public view. The stone itself is used in a variety of ways. The majority of the raw material in the form of crushed rock aggregate is used for road building and the assembly of cement and concrete. It is also used for building decorative stone walls, paving and dwellings, as well as chemically for sugar refining, and in the creation of steel and glass.9

The quarrying industry in the Mendip Hills only began to take off in the 1890s due to increased market access with the building of railway networks.10 However, there is even evidence to suggest the Romans occupied the Mendip Hills because of its limestone outcrop being an invaluable building resource.11 During the interwar period, the demand for the stone increased substantially, sending aggregate to significant

4

Denis Delestrac and Sandrine Feydel, Banking Nature (France: Via Découvertes, 2015). 5 British Geological Survey, Mineral Resource Information In Support Of National, Regional And Local Planning (Frome: Office Of The Deputy Prime Minister, 2005), pp. 5,6. 6 Andrew Farrant, “Lower Carboniferous Rocks (359 To 327 Million Years Ago) | The Rocks Of Mendip | The Geology Of The Mendip Hills | Foundations Of The Mendips”, Bgs.Ac.Uk, 2017 <https://www.bgs.ac.uk/mendips/rocks/lowerC_rocks.htm> [Accessed 3 May 2019].

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Andrew Farrant, “History Of The East Mendip Quarries | Detailed Site Information | Geology And Biodiversity | Foundations Of The Mendips”, Bgs.Ac.Uk, 2017 <https://www.bgs.ac.uk/mendips/more_info/east_mendip_quarries_history.htm> [Accessed 21 June 2019]. 11

// Figure 08: Quarries and Caves in the Mendip Hills as of 1966. Taken from the article: The Impact of Limestone Quarrying on the Mendip Hills by William Stanton. Annotated on the drawing are the locations of quarries mentioned in this dissertation.

Moons Hill Quarry Somerset Earth Science Centre Conversation with an ecologist and geologist Gurney Slade Quarry Conversation with the Quarry owner

Halecombe Quarry Examination of planning submission and restoration plan Whatley Quarry Site research and photographs

Fairy Cave Disused Quarry Site research and photographs Torr Works Quarry National scale of extraction

// Figure 09: Combe Down Quarry. A painting illustrating the extraction of limestone before industrial machinery. Free Stone Quarries. View near Bath. Somerset, 1798.

settlements for the rebuilding of wartime Britain.12 In 1943, the government created Interim Development Orders for mineral extraction,13 a policy that meant quarry owners were instructed to stop extraction on a local scale and to start on a national scale to answer the nation’s needs.14 By 1947, 1.2 million tonnes of limestone was extracted from the Mendip Hills, rising to 3 million tonnes by 1965.15 The first major national environmental legislation in the UK was The Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, but this had little power over quarrying and no way to mitigate the vast amounts of damage already inflicted.

In 2003, 15 million tonnes of limestone was extracted from the Mendip Hills. The two major limestone quarries in the area are Torr Works and Whatley Quarry (Figure 08). Connected by rail, 70% of their 10 million tonnes of annual extraction are transported to London.16

The extraction industry is a sensitive subject for many reasons, the least of which is the removal of a landscape that has formed over millions of years. Open-air extraction is even more damaging due to the loss of surface area flora and fauna, the anthropogenic mark left on a rural environment, in addition to the substantial contribution to carbon dioxide emissions from the transportation and creation of cement. Due to this sensitivity, since the early 1990s, when submitting a planning application for mineral extraction to an existing or new site, quarry owners have been required to submit a restoration strategy in preparation for the afterlife of the site.17 The mineral planning policy in the Somerset Mineral Plan has guidelines which developers are required to abide by. This investigation of this dissertation focuses on a proposal for the restoration by rewilding of Halecombe Quarry under ‘Policy DM7: Restoration and Aftercare’. This kind of proposal usually takes the form of a biodiversity action plan, environmental impact assessments and a restoration draft scheme that expresses the ‘no net loss’ of ecology and the overall benefits of a ‘terraformed’ landscape that was once a quarry (figure 10 shows the current edition of the policy for Somerset County Council).

12 Department for Communities and Local Government, Minerals Planning Guidance 8: Planning And Compensation Act 1991 - Interim Development Order Permissions (IDOS): Statutory Provisions And Procedures(London: GOV.UK, 1991). 13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Department for Communities and Local Government, Minerals Planning Guidance 8: Planning And Compensation Act 1991 - Interim Development Order Permissions (IDOS): Statutory Provisions And Procedures(London: GOV.UK, 1991). 16 British Geological Survey, Mineral Resource Information In Support Of National, Regional And Local Planning (Frome: Office Of The Deputy Prime Minister, 2005), pp. 5,6. 17 J. Gunn and D. Bailey, “Limestone Quarrying And Quarry Reclamation In Britain”, Environmental Geology, 21.3 (1993), 167-172 <https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00775301>.

// Figure 10: Page taken from Somerset Mineral Plan (Development Plan Document up to 2030). Highlighted is the Policy DM7: Restoration and aftercare. The necessity of providing a plan for restoration after extraction has finished.

There has recently emerged a public recognition and convention around the process of ‘greenwashing’ by large corporations, the commonly accepted definition of which is whereby some form of harm to a landscape and its inhabitants is attenuated or disguised behind seemingly well-intentioned environmental activities. However, this dissertation purposely avoids the use of this term as it is often an oversimplification of the mechanics of our economic system. Instead, this dissertation combines fields of knowledge production that have the ability to reveal mechanisms of extractivism. The quarrying companies aim to increase the biodiversity of a post-mineral extraction site, is in itself is a positive ambition. The issue arises when the agendas themselves are interrogated, for restoration plans use a positive means, rewilding, to a negative end: an industry that perpetuates the highly polluting construction industry.

Paradoxically, increasing the abundance of ecologies in disused quarries can have the effect of prolonging limestone extraction—with the associated polluting and environmentally damaging results described above. First, I explore the existing conditions of environmental laws under which the restoration plans are formed, asking whether they bestow rights to nature, or grant the right for nature to be financialised and as a result, damaged. Second, I investigate the limestone quarries’ value to biodiversity through their role as a place for ecological succession, and their propensity to create rare habitats for endangered species to gain an understanding of what ‘wild’ means in this context and to judge the restoration plan to ‘re-wild’ in relation to this. I focus, in particular, on the intricate and often delicate edge conditions of the quarries, known as the ‘ecotone’. Third, I conduct a critical analysis of the restoration plan of the Halecombe quarry as a form of constructed ‘re-wilding’ in relation to the potential for the quarry to return to the ‘wild’ if left alone. Last, using Halecombe Quarry as a case study, I explore the rewilding plans focus on totum species such as the endangered Horseshoe bat. A methodology may increase the numbers of a specific species, but it does so at the potential expense of ecological systems as a whole. This highlights the abstracted nature of biodiversity surveys and action plans which quantify the spread of habitats, and in so doing, oversimplify ecologies. I argue that, despite underlying narratives of environmentalism and a purported desire to mitigate the destruction of the landscape, restoration by rewilding in the Mendip Hills serves as a vehicle for further extraction through the financialisation of landscape and the construction of a damaging and flawed notion of a state of ‘wildness’ to be built through human intervention.

// Figure 11: Author’s image, Fairy Cave Disused Quarry. Aerial photograph taken with a drone highlighting the edge condition between quarry and farmland with increased ecological activity through the process of spontaneous succession. Two climbers are about to scale the quarry wall. April 2019.

_Tensions of terminology_

Conservation, Rewilding, Biodiversity Offsetting, Restoration.

The terminology used in this research has, over time, become loaded and layered with multiple meanings. Here I define the key terms, italicised above, and situate them in relation to existing core texts and theories.

Conservation The Oxford Dictionary defines the term conservation as the “preservation, protection, or restoration of the natural environment and of wildlife.”18 The term, with its positive, prolonged and proactive connotations, has been argued as detrimental to biodiversity.19 In particular, the use of the word ‘preservation’ is contentious as it aims to bubble -wrap ecological systems, with humanity often acting as a self-appointed steward.

Life is in constant flux, morphing at extraordinary rates due to increasing human intervention. Two of the main arguments that question the role of nature conservation are first, the argument for nostalgia; and, second, the argument of human benefit. Both of these begin from the feeling of losing what one had, and therefore what one feels one deserves.20 Conservation requires funding, which in turn is driven by what is publicly thought to be worth saving, which, as Fiedler and Jain argue is “based largely on the appeal to our cultivated biological interests.”21 Given these framings of the politically loaded nature of conservation, I approach the term with a critical understanding of the entanglement between flora and fauna and political motives.

Rewilding Central to my analysis is George Monbiot’s book ‘Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life’, an exploration into the meaning and the practice of the term ‘rewilding.’22 In his book, Monbiot examines whether there is room for traditional nature conservation methods in a world of rewilding.

18

19

20

21 Angus Stevenson, Oxford Dictionary Of English (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2010). Rosaleen Duffy, Nature Crime: How We’re Getting Conservation Wrong (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). Fiedler, Peggy Lee, and Subodh K Jain, Conservation Biology, 1st edn (London: Chapman and Hall, 1992). Ibid.

// Figure 12: Page taken from Somerset Mineral Plan (Development Plan Document up to 2030). Highlighted within the Policy DM7: Restoration and aftercare, Table 7 Reclamation checklist; is the information given about biodiversity offsetting as an ecological mitigation strategy.

To ‘rewild’ is: “to restore an area of land or whole landscape to its natural uncultivated state, often with reference to the reintroduction of species of wild plant or animal that have been lost or exterminated due to human action.”23 Monbiot stresses the importance of wilding, letting an environment return to equilibrium. He writes “[r]ewilding [...] is about resisting the urge to control nature and allowing it to find its own way,” that humans may have to set this in motion at times but should not contain the ecology as if it were in a vivarium.24 There are tremendous benefits in the process of rewilding, and, if done extensively, it has the ability to slow climate breakdown.25 The return of woodlands, grasslands and peat are just some of the ways to absorb massive quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.26

Biodiversity Offsetting In contrast is the concept of biodiversity offsetting. The UK government set in motion a pilot scheme in 2013, which aims to ensure there is ‘no net loss’ when deciding whether a development should happen.27

In other words, biodiversity benefits will compensate for losses to habitats. If a development is going to damage natural habitats and there is no way it can be at first ‘avoided’ or ‘mitigated’ it will be ‘compensated’ in an altogether different location.28 While they appear to be opposing processes, I argue that the case study of the Mendip Hills reveals that the boundary between biodiversity offsetting and rewilding is being blurred in practice.

Restoration The term ‘restoration’ appears in both the definition of conservation and rewilding. Restoration is a word used in the Somerset Minerals Plan policy for the afterlife of quarries. The plan defines it as: “operations associated with the mining and working of minerals and which are designed to return the area to an acceptable environmental condition, whether for the resumption of former land use or a new use.”29 The word ‘acceptable’ is noteworthy in this policy definition, giving developers flexibility when restoring the used quarry. It also gives the extraction company power to decide how the restoration is completed, which includes the choice of habitats implemented and thus, the types of species, and therefore the ability to be targeted.

23 24

Chris Sandom, “Rewilding – Implications For Nature Conservation”, Ecos: A Review Of Conservation, 37(2) (2016), 24-28. Fiedler, Peggy Lee, and Subodh K Jain, Conservation Biology, 1st edn (London: Chapman and Hall, 1992). 25 Rebecca Wrigley, “Rewilding Vs Climate Breakdown”, Rewilding Britain, 2019 <https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/our-work/ rewilding-vs-climate-breakdown> [Accessed 21 June 2019]. 26 Ibid.

27

28 Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs, Biodiversity Offsetting In England(London: GOV.UK, 2013). Ibid. P.4.

// Figure 11 // Figure 10

// Figure 12

// Figure 13: North Somerset and Mendip Bat Special Area of Conservation Guidance on Development. Council providing supplementary guidance for development for the protection of rare bats.

// Figure 14: Somerset News article: Halecombe quarry risk of closure and the impacts on local jobs.

// Figure 15: Somerset News article: Halecombe quarry extension risks affecting the Hot Roman baths of Bath.

Rights What if the limestone, aquifers or the natural springs had a say in the matter, arguing not for the benefit of the economy, but for environmental equilibrium, which in the case of limestone quarries, has several indirect effects on surrounding ecologies and landscapes? Christopher D. Stone’s paper “Should Trees Have Standing? - Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects” was published in the Southern California Law Review in 1972 and expresses the importance of a change in our collective social consciousness,30 from one in which a non-human entity can be freely exploited to one where it is given protective rights.

Stone examines the law of whom—or what—might classify as a holder of legal rights. He proposes three criteria to which a ‘natural object’ must adhere to count judicially in a court of law. First, “that the thing can institute legal actions at its behest,”31 in other words, that their interests can be relayed on their behalf by a person or body, in the same way, the rights of an infant are or even that of a corporation or university. Second, “in determining the granting of legal relief, the court must take injury to it into account,” i.e. the damages that have occurred or might occur to the natural object. Third, “that relief must run to the benefit of it,” i.e. actions that could potentially take place to service a justice to the object. Stone uses the example of a polluted river, with the source of the pollution stopping as a result of this process.

Unlike traditional environmental conservation as defined earlier, the language of rights allows for degrees of flexibility that the structured lists of conservation policies fail to encompass. It also ensures that the interests of the ‘natural object’ maintain the centre point, avoiding political implications and agendas. The open-ended nature of the rights structure also allows for socio-psychological changes to occur, with the hope for a move away from individualistic capitalist motives towards non-anthropocentric holistic care.

30 Christopher D Stone, Should Trees Have Standing?, 3rd edn (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010). Ibid. P.4.

// Figure 16: Whatley Quarry, 2001 condition. Satellite image taken from Google Earth.

// Figure 17: Whatley Quarry, 2018 condition. Satellite image taken from Google Earth. It takes up the entire width of the carboniferous limestone belt. The restoration strategy has not changed since it was drawn up 30 years ago, an is now out of date. The owners are under no obligation to make any amendments to the scheme.

// C1

// Figure 18: Author’s image, Whatley Quarry, concrete and asphalt plant positions within the large void of the quarry. Water body on the left of the image comes from aquifers and is constantly being pumped out and fed back into the water systems. Diggers at the bottom of the image stockpile the crushed rock aggregate. December 2018.

_Entanglements of economy, sociality and ecology in the Mendip Hills community_

Areas of mineral extraction have historically always led to conflicts of interest between local communities, human and non-human residents and corporations with human influenced erosion. Erosion as a result of human activity is now 600 times greater than natural rates .32 Mining in the Mendip Hills is the most important industry for the local economy, providing jobs in the quarrying and countless subsidiary industries .33 This economic and social entanglement results in a need for continued environmental degradation to support livelihoods, forcing local communities to be complicit in the destruction of their own environments despite some local residents protesting the noise, dust, visual pollution and the vibrations caused by extraction explosives .34 The national (and international) nature of the industry further binds locals to global scale networks of extraction, further alienating them from being able to influence change in the Mendip Hills.

In the case of the Mendip Hills limestone extraction, there are several conflicts which this dissertation will analyse in the following three chapters. Firstly, the economic system: the case for the Quarry owner and the need to make as large a profit as possible, combined with the provision of employment for many people in the area. Moreover, there is the case for development, the need to build, improve and maintain roads and other forms of infrastructure and the construction industry’s requirement to house the growing population .35 Secondly, on the opposing side of the argument, there are the rights for a landscape to remain untarnished and protected from environmental decay from industrial pollutants as well that from heavy vehicles transporting extracted minerals through sensitive countryside. There are additional implications for hydrological systems when extracting from karst terrains or below the water table due to its geological composition which has lasting effects on humans and other-than-humans .36 Thirdly - and the main focus of this dissertation - is the argument for the ecological gain brought by the post-quarry landscape in the Mendip Hills. Once extraction is over, these areas are ‘rewilded’ through biodiversity action plans and

32

Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993).P.31. 33 Andrew Farrant, “Introduction | Quarrying And The Environment | Quarrying | Foundations Of The Mendips”, Bgs.Ac.Uk, 2020 <https://www.bgs.ac.uk/mendips/aggregates/introduction.htm> [Accessed 24 July 2020]. 34 Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993). P.17

35 36 Ibid. P.3.

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Active Limestone Quarries

Government Safeguarded Limestone Deposits

// Figure 19: Somerset Mineral Plan policies map. Author overlay, Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty designation and active quarry locations. High density of quarries in East Mendip and low density of quarries in West Mendip

fenced zones, separating public footpaths from the quarry and allowing flora and fauna to return including a number of endangered species. Is the removal of a monoculture ecology like farmland for a diverse and scarce habitat like the rock face of the quarry reason enough for continued extraction to take place?

Limestone terrains usually comprise diverse landscapes due to the minerals and land formations and are aesthetically appealing. The Mendip Hills are no exception and were given the conservation status of AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) in October 1989 .37 Interestingly, the AONB was assigned to half of the limestone terrain of the Mendip Hills as opposed to all (figure 19) .38 Where the AONB status overlaps with limestone terrain, there are no active quarries, only several small older disused quarries. However, the AONB status does not include areas where there is a high-density of large and small working and disused quarries .39 The partial designation of the Mendip Hills as an AONB poses the question of how those with power define the value of the landscape. Should it be based on the human desire for an appealing view or its ecological significance, or more worryingly, the possibility for wealth from mineral extraction as appears to have been the case? There is a debate as to whether the presence of quarries in east Mendip, where Whatley Quarry and Torr Works lie, resulted in the area not being protected under an AONA. As it is not classed as an area of outstanding natural beauty it has been stripped of much of its karst terrain.

This dispute was brought to my attention by chance conversation in 2015 with a wind turbine owner. The person (whose name I never knew) stated that part of the reason AONB did not cover the entirety of the Mendip Hills was the significance of economic gain of limestone extraction was too great, as the AONA status would fiercely regulate the quantity of extracted minerals . This is another example where instead of protecting an environment policy can be viewed as the legitimation of damages. As architects, our understanding of context is at times limited to direct relationships in geographic terms. This example reveals the importance of the indirect relationships, geographic and legislative, as a way to understand disputed territories.

37 Naturalengland-Defra.Opendata.Arcgis.Com, 2019 <http://naturalengland-defra.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/areas-of-outstanding-natural-beauty-england?geometry=-4.214%2C51.025%2C-0.122%2C51.626> [Accessed 2 May 2019]. 38 Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993). 39 William Stanton, The Impact Of Limestone Quarrying On The Mendip Hills, 1st edn (Bristol: University of Bristol Speleological Society Proceedings, 1966), pp. 54-62.

// Figure 20: Graph of global population growth and cement production from 1950 to 2015. Taken from Journal of Cleaner Production 167 (2017) 365e375

_Situating extraction in the Mendip Hills in relation to wider ecological degradation through construction_

“Human activities have caused the planet’s average surface temperature to rise about 1.1°C since the late 19th century. Most of the warming occurred in the past 35 year”.40

The quarrying industry in the Mendip Hills has caused debate for many decades. Opinions have changed with policy implementations appearing slowly, sometimes several years after they are requested. Views on environmental degradation have begun to reach the mainstream media, most recently with the protest of activist group ‘Extinction Rebellion’ in April 2019 who succeeded in reaching out to the masses in the UK demanding urgent action on climate breakdown.

The limestone extracted from the Mendip Hills quarries has several uses within the construction industry, including through the creation of cement. The cement industry is accountable for 5% of global carbon dioxide-emissions .41 The emissions fill our atmosphere and are partly responsible for the alarming speed the Earth has begun and will continue to warm. This pollution comes from both the highly energy-intensive process of cement production and as a by-product of the calcination process. There are three main steps to the cement process: the preparation of the limestone, the clinker-making and the cement making. The preparation of the raw material uses large amounts of electricity through the grinding down of the stone. Then, calcination occurs when fine limestone is heated to very high temperatures to create a clinker product and from this, the cement is made. During the calcination, the limestone is put under 1450°C heat which is responsible for 70-80% of the total energy used .42

Cement is used prolifically in the construction industry due to its hydraulic binding properties. When cement is mixed with water it creates a paste which hardens and retains its strength due to the formation of

40 “Extinction Rebellion - The Emergency”, Extinction Rebellion, 2019 <https://rebellion.earth/the-truth/the-emergency/> [Accessed 21 June 2019]. 41 C.A. Hendriks and others, “Emission Reduction Of Greenhouse Gases From The Cement Industry”, Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies 4, 1999, 939-944 <https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043018-8/50150-8>. 42 Ernst Worrell and others, “CARBON DIOXIDE EMISSIONS FROM THE GLOBAL CEMENT INDUSTRY”, Annual Review Of Energy And The Environment, 26.1 (2001), 303-329 <https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.26.1.303>.

// Figure 21: Diagram showing the effects of sub-water table quarrying on groundwater levels in a limestone aquifer. Taken from Mendip Limestone Quarrying, A Conflict of Interests, 1994.

hydrates in the material. It is an inorganic and nonmetallic material that due to its chemical composition is energy intensive to breakdown and recycle, thus a very unsustainable building resource .43 When speaking to a local geologist, we discussed the industry ambition for increased use of recycled building materials, however, these materials have not passed the sufficient binding tests for it to replace the extraction of new materials .44 Furthermore, it is in the quarries’ interest for this to remain the case.

“Quarrying has already shrunk or polluted seven East Mendip springs that once were large and clear” .45

The limestone quarries of the Mendip Hills are particularly susceptible to changing the hydrological system in the area. Limestone differs from other stone as the rock is at risk to dissolution due to waters circulating within the geology. This type of terrain is known as karst. There are several features which can be identified in this landscape which make it distinct, such as, sinking streams, dry valleys and caves and a lack of surface water flow .46 The subcutaneous zone is the area near the surface where dissolution is more frequent due to carbon dioxide produced by decomposing organic matter. It is important that water filters through this section to reach vertical fissures and overtime form shafts that travel through the unsaturated zone to reach a network of caves. The Mendip Hills are made up of hundreds of these systems which form the basis of aquifers .47 These aquifers are essential for ecological systems as well as human and other-than-human used springs. There have been several cases where quarrying in the Mendip Hills intersects these networks, altering the hydrology thus having unknown indirect effects. Fairy Cave Quarry in East Mendip, which intersected a 4.5km cave network serving a spring,48 is a prime example of mineral exploitation lacking regard for its environmental context. Fairy Cave Quarry was subsequently abandoned due to the damage done to the hydrological system exposure .49

43 44 Ibid.

Meeting with an ecologist and a geologist at the Somerset Earth Science Centre (Somerset, June 13th, 2019).

45 46

47 Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993).P.31. Ibid. P.17-23.

Ibid. P.17-23. 48 Andrew Farrant, “Water And Caves | Quarrying And The Environment | Quarrying | Foundations Of The Mendips”, Bgs.Ac.Uk, 2017 <https://www.bgs.ac.uk/mendips/aggregates/environment/water.html> [Accessed 2 May 2019]. 49

// Figure 22: Shatter Cave at Fairy Cave Quarry. Photograph taken by Steve Sharp, July 2013.

Caves are particularly significant in karst terrain and a distinctive feature of hard carboniferous limestone. They are used as a vital resource for understanding geological compositions and also accumulate sediment once the streams that formed them have been depleted. These deposits which arrive from the surface are preserved from subaerial erosion .50 They can be accurately dated and provide valuable information on the condition of the Earth’s flora and fauna. Quarrying has been the cause of many of these caves in the Mendip Hills being destroyed, even if for a short period of time they are allowed to be examined. Other geomorphic impacts of limestone are the removal of ‘relicts’ which are geological forms which appear on the surface but are formed during a very different geological period .51

There is blood in the stone, with the removal of minerals, geological records, which alters hydrological systems, comes the destruction of flora and fauna. One of the main issues with quarrying is it is difficult to gauge the extent of damage before it is done. Thus the proposal of restoration through biodiversity action plans distracts from the damage as it provides an easily understood offset to the destruction.

50

Frank Raymond, Mendip Limestone Quarrying (Tiverton: Somerset Books, 1993).p.17-23. 51 U.S. Geological Survey, Potential Environmental Impacts Of Quarrying Stone In Karst- A Literature Review, Version 1.0 2002 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2001) <http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/ofrs/OFR-01-0484/> [Accessed 2 May 2019].

// Figure 23: Image taken by Christina White of Halecombe Quarry showing the impact of blasting on limestone quarrying.

_The rights of limestone_

Using C. Stone’s logic of rights and applying it to the limestone extraction industry,52 I would argue that limestone has a right to maintain in its bedrock location, where it has existed for over 300 million years. The challenge here is to avoid anthropomorphising limestone. One can easily relate to the struggles of an endangered species because it has desires to which humans can comprehend. The argument is to maintain the geology for the sake of maintaining the geology, because it belongs in the ground where it was formed, and because it is finite, once removed it will never return - not because it provides a source of clean water for humans and other-than-humans. The further we travel into the 21st Century the more humanity has come to realise we cannot consume our way to transcendence.

The process of industrialisation has exacerbated the consumption of the natural world. In order to induce a change in our collective consciousness, it is important to understand the process humanity has undergone to arrive at where we are today, teetering on the edge of collapse.

“Globally species are going extinct at rates up to 1,000 times the background rates typical of Earth’s past. The direct causes of biodiversity loss being habitat change, overexploitation, the introduction of invasive alien species, nutrient loading and climate change.”53

C. Stone argues that the ‘domination of Man’ as the foremost power within nature began (in western cultures) from religious traditions. He argues that our current consciousness is one of Humanist values placing prime importance on the human, derived, he argues, from Christianity and earlier Judaism .54 Both Christianity and Judaism place ‘Man’ as being exclusively divine, with non-humans being insignificant by comparison. The natural world’s jurisdiction was given to humans to do with as they wished from an early stage in our cultural development. Moreover, our popular consciousness was defined further by the Darwinian theory of evolution. The idea that the development of humans came about by chance happenings leads to the

52

Christopher D Stone, Should Trees Have Standing?, 3rd edn (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010). 53 Ahmed Djoghlaf, “UNEP Report – Global Biodiversity Outlook 2”, Management Of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 21.6 (2010),p. 6 <https://doi.org/10.1108/meq.2010.08321faf.001>. 54

// Figure 24: The Tree that Owned Itself in the city of Eufaula, Alabama. It was deeded to itself in 1936. When it died the deed was handed down to another oak tree whose seed came from the original tree. Unknown photographer.

belief that this would continue without regard for the environmental context .55 The theory unintentionally results in the reduction of our awareness of the importance of nature for our own existence as well as for that of millions of other species. Currently, it is undervalued within our economic system, the opportunity for wealth taking precedence over environmental care .56

Since Stone’s paper, environmental laws and policies have been implemented all around the world, but counter to his rights-based laws, it is legislation that allows for the destruction of the planet. The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) is a US-based company that provides legal advice, legislation and support for local communities for the rights of nature. It is a development from the work of Stone against the current environmental legislation that conforms to corporations commodifying a landscape. Mari Margil, an associate director at CELDF, articulates the entanglements between policy and planetary degradation thus, ‘[current] environmental law is primarily to authorise and legalise environmental harm [...] known environmental harm that is inherently unsustainable’ .57

I argue that the ‘Somerset Minerals Plan: Development Plan Document up to 2030’ is an example of this form of governance .58 The Somerset Minerals Plan takes into consideration the affected parties of mineral extraction but does so to ensure that extraction can continue into the future. I will articulate the ways in which this is done below in Chapter 2 and 3.

The ‘Policy DM7: Restoration and aftercare’ in the Somerset Minerals Plan loosely considers the environmental implications of the development through a ‘Reclamation Checklist’ (figure 12),59 its criteria is broad and vague, ensuring the proposal satisfies the requirements of environmental groups and the law.

55 56 Ibid. P.26.

Denis Delestrac and Sandrine Feydel, Banking Nature (France: Via Découvertes, 2015).

57

58

Mari Margil, “Offsetted: On The Rights Of Trees”, 2019. Somerset County Council, Somerset Minerals Plan (Taunton: Somerset County Council, 2015). 59 Somerset County Council, Somerset Minerals Plan (Taunton: Somerset County Council, 2015),p. 93. “18.7 Site-specific detail will vary and so the planning policy framework offers a degree of flexibility, with the checklist highlighting, in particular, the cases where certain criteria are of greater importance.”

// C2

// Figure 25: Author’s image, disused smaller quarry adjacent to Halecombe quarry. Extraction finished 30 years ago. Spontaneous ecological succession has taken place and it now contains a plethora of habitats. Local ecologist recounts seeing ravens and peregrine falcons nesting here, both of which are extremely rare. April 2019.

_ From the rubble: restoration by rewilding_

The limestone quarrying industry has entered into a new sphere of stakeholder relations to ensure that their ‘social license’ of continued extraction is maintained.60 As well as this proactive focus of reaching out to environmental groups, the industry is required to quantify their impact and benefit to habitats. I conducted an interview with the owner of a mid sized quarry in the Mendip Hills, much of the discussion revolved around how opinion on limestone quarrying reclamation is in constant flux. He said “a good reclamation plan 20 years ago to return the land back to agriculture is now thought of as completely wrong”, he went on to say “the planning process tries not to be too prescriptive so the reclamation plan can adapt to current thinking” .61

While it appears to be responsive to contemporary thinking and developments, this is a destructive situation. It means that quarry restoration can reach out to the general consensus of environmentalists by putting whatever is of current interest into their biodiversity action plans, thereby convincing both the planners and environmental groups of the benefits of their proposals. In other words, it is relatively straightforward to convince the environmental stakeholder that usually would be opposing a site of mineral extraction, that it contains ecological benefits. Deeper interrogations of the Mendip Hills quarries reveals them as a significant contributor to national carbon emissions. Companies that make monetary gains directly from the destruction of a local landscape but also from significant contributions to global warming should not be able to veneer their damages with specific, small scale rewilding. They aim to be fully transparent in the restoration process, ensuring they work with environmental groups from the beginning.

In addition, that there is usually a minimum of a 40 year buffer period between an application for extraction and the creation of the promised habitats by which time the damage would already be done to subsequent ecological stakeholders and, as the quarry owner said, the original plan for restoration would be very out of date, moreover, millions of metric tonnes of limestone would have been extracted, contributing to carbon emission in our atmosphere.

60 Adisa Azapagic, “Developing A Framework For Sustainable Development Indicators For The Mining And Minerals Industry”, Journal Of Cleaner Production, 12.6 (2004), 639-662 <https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-6526(03)00075-1>. 61

// Figure 26: Author’s image, Fairy Cave Disused Quarry. Aerial photograph taken with a drone highlighting the edge condition between quarry ledge and the wilderness margin area that attracts endangered species. April 2019.

However, adding to the complexity of this political ecology of limestone extraction is that of the actual ecological benefits to habitats and biodiversity of the post-extraction quarry. The current landscapes that surround the Mendip Quarries are predominantly made up of intensively farmed land. This land is largely a monoculture environment - only the field divisions that take the form of hedgerows remain highly important for flora and fauna and provide habitat corridors.62 The forms of post-extraction quarry ledges, provides heterogeneous surfaces, a clean ‘slate’ for pioneer species to colonize. It is this edge condition that we lack in our farmland. The edge condition is also known as ecotone where two landscapes meet. It is this edge where increased ecological activity takes place, the jagged jock faces creating various microclimates for a variety of species to colonise.63

The quarry ledge provides a locality that is rare within human crafted landscapes of forestry, farming and settlements.64 Several studies have been undertaken that stress the importance of the ecosystems that these habitats form in creating resilient ecologies of flora and fauna .65 It is concerning, however, that this benefit emerges from the commodification of a raw material. I would argue that the limestone extraction industry now relies on these ecological benefits for the continuation of their industry. There forms an unusual juxtaposition of rare pioneer plant species and endangered animals within the scaleless destructive blasting of limestone extraction, the former endorsing the latter.

There are two schools of thought about the post extraction site of a karst terrain limestone quarry. The first, and the one practiced by all current restoration plans, is that of a ‘technical restoration’ which involves planting trees and shrubs and sowing seeds in a layer of topsoil which has been brought to the site. The second is that of ‘spontaneous succession’ which involves no planting or seeding of flora. This was what happened to quarries before planned restoration requirements were instigated over 25 years ago. The postextraction landscape was left to the ‘wild’, the process of ecological succession which took place organically. The movement towards a culture of sustainable development in the 1990’s encouraged quarries to use the ecological significance of this process to their own advantage through the implementation of planned restoration schemes.66 The Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD) project which is part of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) is the body which has assured a

62 Robert Tropek and others, “Spontaneous Succession In Limestone Quarries As An Effective Restoration Tool For Endangered Arthropods And Plants”, Journal Of Applied Ecology, 47.1 (2010), 139-147 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01746.x>. 63 Meeting with an ecologist and a geologist at the Somerset Earth Science Centre (Somerset, June 13th, 2019).

64

65 Ibid.

Ibid.

66 “Mining, Minerals And Sustainable Development (MMSD)”, International Institute For Environment And Development, 2019 <https://www.iied.org/mining-minerals-sustainable-development-mmsd> [Accessed 13 June 2019].

// Figure 27: Image taken from the book Mendip Limestone Quarrying, A Conflict of Interests, 1994 illustrating the damaging technical restorations that took place when the restoration policy first arrived in the 90’s.

smooth transition .67 However, a comprehensive comparative study into both methods of restoration in limestone quarries challenges the need for a planned restoration .68 The results proved that there is no benefit to ecology when using the ‘technical restoration’ method but, there were benefits when opting for ‘spontaneous succession’ .69

One of the differences between the two methods is the technical restoration’s implementation of the soil and seed mixture. This seed mixture favours the fast growing ruderal vegetation that are competitive plant species, and the more sensitive, rarer, pioneering flora being unable to grow alongside them in these habitat .70 The results of the technical restoration are more ground covered flora, giving the appearance of a proactive, productive scheme to an outsider looking in. The process also works faster than spontaneous succession as plant species are carefully selected then translocated from other sites in the local area .71

However, I would argue that human bias plays a role in the way we care for the natural world. Restoration with a productive goal is firstly, a “utilitarian view of landscape” and secondly an “ingrained equilibrium view of natural communities”.72 Both are based in capitalist ‘net gain’ theories and have been dismissed by ecologists. Disturbances are common amongst natural processes and make room for a coexistence of species which cannot be imitated by humans during technical restoration.

On the other side of the argument, the process of ensuring a restoration of a quarry gives the post-industrial landscape a very new meaning. It transforms ‘unproductive’ wasteland to a productive wilding ecological site. Moreover, the land is most probably removed permanently from the sphere of development, given back to nature after centuries of human influence. The amount of benefit this could create is substantial with “mining areas representing almost 1% of the world’s land”. If effective restoration were to take place on this amount of land it would contribute significantly to the slowing down of the climate breakdown .73

The issue comes back to the speed in which this process takes place. The fact that years of extraction are locked into our timeline through a promise of wilding in the future is not an adequate response to mineral

67 Ibid.

68 Robert Tropek and others, “Spontaneous Succession In Limestone Quarries As An Effective Restoration Tool For Endangered Arthropods And Plants”, Journal Of Applied Ecology, 47.1 (2010), 139-147 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01746.x>. 69 Ibid.

70

71 Ibid.

Meeting with an ecologist and a geologist at the Somerset Earth Science Centre (Somerset, June 13th, 2019). 72 Robert Tropek and others, “Spontaneous Succession In Limestone Quarries As An Effective Restoration Tool For Endangered Arthropods And Plants”, Journal Of Applied Ecology, 47.1 (2010), 146 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01746.x>. 73 Rebecca Wrigley, “Rewilding Vs Climate Breakdown”, Rewilding Britain, 2019 <https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/our-work/ rewilding-vs-climate-breakdown> [Accessed 21 June 2019].

// C3

// Figure 24

// Figure 25

// Figure 28: Habitat type bands, taken from Biodiversity Offsetting Pilots, Technical Paper: the metric for the biodiversity offsetting pilot in England, March 2012

// Figure 29: Table of habitat types in the UK (page 1 of 12) from the Appendix 1 - Distinctiveness Bands for the Biodiversity Offsetting Pilot.

_An investigation into Halecombe Quarry Restoration Strategy_

extraction.

A balance must be found for a restoration strategy. The current methods are too prescriptive based on national requirements that choose specific kinds of habitats to protect, in some cases based on a human centric desire rather than ecological. I have used a case study to investigate the effects of the quarry restoration process using the most recent planning submission of a limestone quarry development in the Mendip Hills. Halecombe Quarry, situated in North-East Somerset near Frome was approved for planning in 2017. The quarry was threatened with closure by the end of 2019 due to its limited reserves of limestone at its current level. Tarmac, the UK’s largest supplier of construction materials operates Halecombe and submitted an extension to excavate a further 60 metres deeper in April 2017 that was approved in May 2017.74

This made available 16.5 million tonnes of limestone that would ensure production until the mid 2040’s. This would be followed by a two year reclamation plan .75 The quote below is taken from the Halecombe quarry website evidencing the scale of production from the quarry:

“The quarry produces around 80 cubic meters of concrete, 1,200 tonnes of asphalt 2,500 tonnes of aggregate per day. Annual production of all stone products is typically between 500,000 to 700,000 tonnes per year with an annual maximum limit of 900,000 tonnes.” 76

This level of production has significant impacts on the environment in terms of the carbon emissions released in all areas of the extraction process and particularly the production of concrete. However the offsetting plans are based solely in hectares squared rather than carbon emissions.

In 2012, a technical paper was published by the UK government from the Department of Environment,

74 “About Halecombe Quarry | Frome, Somerset”, Tarmac.Com, 2019 <https://www.tarmac.com/halecombe-quarry/about/> [Accessed 12 June 2019]. 75 Daniel Mumby, “140 Jobs At Quarry Near Frome Saved At Eleventh Hour After Being Threatened With Closure”, Somerset News, 2018 <https://www.somersetlive.co.uk/news/somerset-news/frome-quarry-saved-140-jobs-2214151> [Accessed 21 June 2019]. 76 “About Halecombe Quarry | Frome, Somerset”, Tarmac.Com, 2019 <https://www.tarmac.com/halecombe-quarry/about/> [Accessed 12 June 2019].

// Figure 30: Halecombe Quarry, 2001 condition. Satellite image taken from Google Earth

// Figure 30: Halecombe Quarry, 2018 condition. Satellite image taken from Google Earth

// Figure 32: Halecombe Quarry, 2017 Planning submission Existing condition.

// Figure 33: Halecombe Quarry, 2017 Planning submission Final stage of extraction, 2045.

// Figure 34: Halecombe Quarry, 2017 Planning submission restoration plan for 2047.

Food and Rural Affairs. The paper titled; ‘Biodiversity Offsetting Pilots, Technical Paper: the metric for the biodiversity offsetting pilot in England’ puts forward a system in which particular habitats get favourable recognition when offsetting the damage done by industry.77 There are three habitat type bands which the metric puts forward, with habitats are assigned to the different bands based on their ‘distinctiveness’.

“Distinctiveness includes parameters such as species richness, diversity, rarity (at local, regional, national and international scales) and the degree to which a habitat supports species rarely found in other habitats”

78

Within the top tier of habitats there is a wide range in ‘distinctiveness’ as defined by the paper. There are 258 habitats given the title of ‘High’ priority, compared with 41 given ‘Medium’ priority and 38 habitats given ‘Low’ priority .79 This means there is a high degree of flexibility in the top tier which makes an offsetting scenario favourable for developers. ‘Priority Habitats’ with limited similarities are traded in order to achieve a ‘no net loss’ with the decision making responsibility in the hands of the quarries.

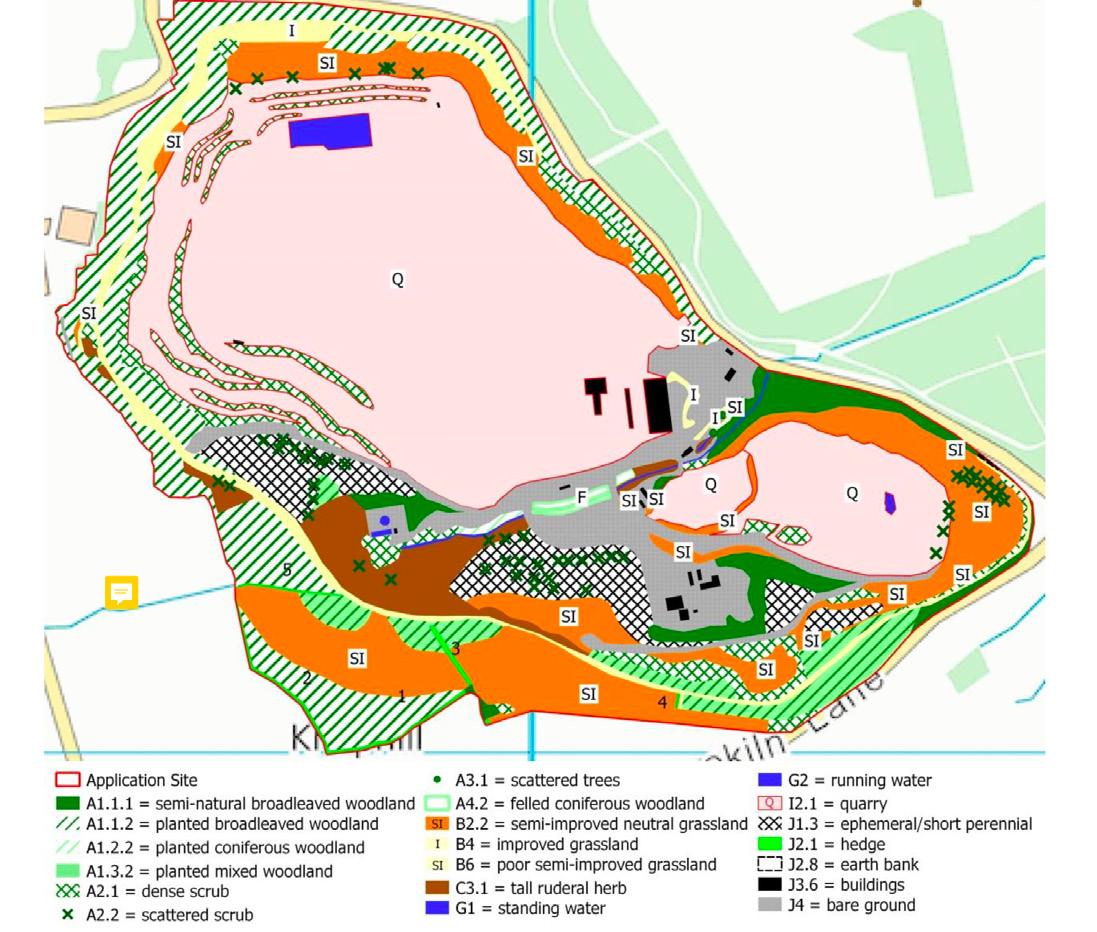

The Halecombe quarry reclamation plan revolves around creating a ‘net gain’ to these top tier ‘Priority Habitats’. An ecological survey was commissioned in 2015 into the area in and around the quarry with 21 habitats types recorded, 11 of which are classified within the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) Priority Habitats, Somerset Local BAP Priority Habitats and Mendip Local BAP Priority Habitats .80 To quantify the damages and compensation required for the site ‘Valued Ecological Receptors’ (VER) are classified for the area of analysis. These include the ‘priority habitats’ classification as well as two ‘important’ hedgerows, two plant species, 65 invertebrates, one reptile species, 28 bird species, one mammal species (excluding bats) and 14 bat species .81 The impact assessment is formed by a desk study followed by surveys if necessary. From this the ecologist makes assumptions on projected net gains and net losses for each VER.

77 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Biodiversity Offsetting Pilots. Technical Paper: The Metric For The Biodiversity Offsetting Pilot In England (London: GOV.UK, 2012). 78 Ibid.

79 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Appendix 1 - Distinctiveness Bands For The Biodiversity Offsetting Pilot (London: GOV.UK, 2019). 80 Andrews Ecology, ECOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF LAND AT HALECOMBE QUARRY, LEIGH-ON-MENDIP, FROME, SOMERSET, BA11 3RD, Deepening Of Halecombe Quarry By Extraction Of Limestone (Bridgewater: Mendip District Council, 2017) <https:// publicaccess.mendip.gov.uk/online-applications/files/BC1685F60AD3F27C9F6BF68B35643B4B/pdf/2017_1022_CNT-ECOLOGICAL_IMPACT-232324.pdf> [Accessed 16 June 2019]. 81

// Figure 35: Halecombe Quarry, Habitat Type classifications marked on the Site

// Figure 36: Halecombe Quarry, 2017 Planning submission restoration plan for 2047. The water body increases in size substantially and the geodiversity and exposed rock faces decrease.

// Figure 37: Net gains and net losses shown in a table in the Ecological Impacts Assessment carried out by Andrews Ecology in 2017. The quantification of habitats make some compensable.

There are numerous issues with an ecological survey funded by the company that owns the quarry. The areas of habitat loss and gain are calculated and put into a table and classified as negative impact of high and low magnitude and positive impact of high and low magnitude. It is based on surface area of habitats measured in hectares which enforces a radically simplified view of landscape. This is problematic for the species that are most rare and most beneficial for landscape biodiversity. For example, according to the ‘Ecological Impacts Assessment’ the ‘Ephemeral/short perennial (J1.3)’ is a phase 1 priority habitat that emerges from post-industrial sites, living short lives and being particularly useful for ecological succession .82

It has a net loss of 2.97 hectares (29700 meter squared) compared with a net gain of 15.27 hectares (152700 meter squared) of standing water, which is equally a phase 1 priority habitat .83 In other words, a comparison is being made between the removal of rare pioneering plant species, very valuable for biodiversity, and flooding the extraction crater to create the ‘standing water’ habitat. The ephemeral plants would attract many species of invertebrates which in turn benefit the bird and bat populations, whereas the crater is 500 meters by 250meters. (Today it is 88 meters deep, but it will be 148 meters deep by 2045 ).84 To flood the crater all they are required to do is to stop pumping the water out of it. It will naturally fill from the aquifers as it will be 80 meters below the water table .85 It is troublesome that these two very different environmental conditions are being valued in the same way in terms of surface area and their ‘Priority Habitat’ recognition. When extraction stops there will always be a net loss of industrial land and a net gain of habitat types, therefore, the situation will always flatter the proposed restoration plans, making the planning submission process straightforward and convincing.

82 49. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions (Peterborough: GOV.UK, 2011), p.

83 Andrews Ecology, ECOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF LAND AT HALECOMBE QUARRY, LEIGH-ON-MENDIP, FROME, SOMERSET, BA11 3RD, Deepening Of Halecombe Quarry By Extraction Of Limestone (Bridgewater: Mendip District Council, 2017) <https:// publicaccess.mendip.gov.uk/online-applications/files/BC1685F60AD3F27C9F6BF68B35643B4B/pdf/2017_1022_CNT-ECOLOGICAL_IMPACT-232324.pdf> [Accessed 16 June 2019]. 84 Ibid.

// Figure 38: Mineral Products Association. mpa: essential materials sustainable solutions. Leaflet stating the dangers of quarry water bodies.

In addition, all of the nine working quarries in the Mendip Hills have proposed very large, very deep bodies of water in their restoration plans, with limited ecotone edge conditions that actually benefit biodiversity. The biodiversity offsetting plan places an emphasis on maintaining the character of the environment that has been lost, “habitats that are of high distinctiveness would generally be expected to be offset with “like for like i.e. the compensation should involve the same habitat as was lost” .86 In none of the cases did a large body of water exist before extraction, once more, the post extraction quarry becomes paradoxical in a realm of policy and legislation and development plans. Moreover, the quarries have a responsibility to local communities in their restoration plans as well as to the environment. These large bodies of water are lethal environments for its human inhabitants. There has been several cases of young people dying when jumping into Mendip Hills disused quarry water .87

86 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Biodiversity Offsetting Pilots. Technical Paper: The Metric For The Biodiversity Offsetting Pilot In England (London: GOV.UK, 2012) P.4. 87