20 minute read

A review of necrotising herpetic retinopathies: acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis

REVIEW ARTICLE: A review of necrotising herpetic retinopathies: acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis

I Walters MBBCh(Wits), B Optom(RAU/UJ); Registrar in the Division of Ophthalmology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9159-8930

Advertisement

A Makgotloe MBBCh(Wits), MMed(Wits), FCOphth(SA); Academic Head: Division of Ophthalmology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8193-3245

Corresponding author: Dr Ingrid Walters, PO Box 52281, Saxonwold, 2132; tel: +27 82 573 1023; email: ingrid.walters@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

Purpose of review: Necrotising herpetic retinopathies are a group of debilitating retinal disorders of which acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis are important examples. They are uncommon, rapidly progressive, and devastating posterior segment syndromes caused by human herpes viruses. The clinical picture is influenced by the patient’s immunological status and viral factors.

The authors present a review article on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and management of acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis.

Recent findings: Although a clinical diagnosis, polymerase chain reaction has become a diagnostic modality of choice in the management of patients with necrotising herpetic retinopathies. Treatment is high dose induction dual intravitreal and systemic antiviral therapy followed by a prolonged period of maintenance therapy. Prophylactic laser retinopexy and early vitrectomy are no longer advocated, as there is lack of supporting evidence. Despite early diagnosis and best treatment, acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis carry guarded prognoses and patients should be counselled appropriately.

Keywords: progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome, acute retinal necrosis syndrome, necrotising herpetic retinopathy, varicella zoster virus, retinitis, polymerase chain reaction

Funding: All research was funded by the principal author.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Introduction

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) was first described in immunocompetent, healthy adults in Japan by Urayama et al. (1971). They described acute unilateral panuveitis with retinal periarteritis and rapidly progressive diffuse retinal necrosis with subsequent retinal detachment.1 Culbertson et al. (1982) first described histologic evidence of a likely herpetic aetiology.2 It was not until 1994 that the Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society developed and published standardised diagnostic criteria for ARN.3

Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN), the variant of necrotising herpetic retinopathy, found almost exclusively in profoundly immunosuppressed patients, was first described by Forster et al. (1990). The condition is characterised by multifocal areas of retinal opacification originating in the outer retinal layers, little to no ocular inflammation, rapid progression of lesions to confluence and early posterior pole involvement.4 Margolis et al. (1991) presented clinical and laboratory evidence suggesting this was a form of varicella zoster virus (VZV) retinopathy.5

Guex-Crosier et al. (1997) concluded that ARN and PORN, while being distinct clinical entities, fell on opposite ends of the spectrum of necrotising herpetic retinopathies as they share a causative viral aetiology. The degree of host-immune impairment seems to determine the type and severity of the syndrome with various intermediary clinical forms in between.6

Methods

A Pubmed database search was conducted to find recently published, original English articles concerned with the topic of necrotising herpetic retinopathies. Relevant articles including reviews were included. All important publications, mostly retrospective studies and case reports, were reviewed and included. All research included is in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Epidemiology

ARN is rare, comprising approximately 1–2% of endogenous uveitis cases.7 It affects woman and men equally. Typically described as affecting healthy young adults, it can also affect the elderly, as well as children.7-9

Although ARN often occurs acutely in healthy, immunocompetent patients, ARN has been described in patients with HIV infection and in those taking immunosuppressive agents.7,9 Studies suggest possible specifically diminished cellular immunity to VZV in the absence of systemic immunosuppression or a possible diminished local immunity in the eye.6,9 Genetic predispositions may exist.9

Most ARN sufferers have no preceding prodrome and no relevant systemic diseases; however, cases of ARN occurring with past or concurrent herpetic encephalitis or meningitis have been reported.9,10 In 1978, Young and Bird coined the phrase bilateral acute retinal necrosis (BARN), which is now known to occur in up to 70% of untreated patients.10,11

In immunocompromised patients PORN is the second most common infectious retinitis after cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis.12 It generally affects young adults with an equal sex distribution.12,13

PORN has most commonly been described in immunosuppressed individuals secondary to advanced HIV infection, with mean CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of 21 cells/µL (range 0–130 cells/µL).13 In a large South African case series of PORN patients by Gore et al., all patients were found to be HIVpositive with mean CD4 lymphocyte count of 30 cells/µL.14 PORN has also occasionally been described in other settings of immunosuppression such as lymphoma, immunosuppressive medications like corticosteroids or chemotherapy, nephrotic syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and graft-versushost disease.12 Approximately 66% of cases are associated with preceding or concurrent cutaneous herpes zoster infection.13,14 PORN, like ARN, typically manifests unilaterally before affecting the fellow eye in 71% of cases.12,13

Aetiology

ARN results from a reactivated latent herpes viral infection. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) remains the most frequent cause and tends to affect older patient populations as VZV immunity wanes.9 Human herpes virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are usually acquired in childhood. Reactivation of HSV-1 tends to cause retinitis in older patients and HSV-2 tends to affect younger populations.8,9 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are reported, albeit exceedingly rare causes of ARN.7

Evidence proving that VZV is the commonest cause of ARN, followed by HSV-1 and 2 and very rarely CMV and EBV is strong. The viruses have been isolated and identified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based techniques, serum and intraocular fluid antibody testing, viral culture, immunohistochemistry and retinal biopsy.8,9 Histology demonstrates intranuclear viral inclusions within inner layer retinal cells, full thickness retinal necrosis and arteritis.9

PORN is caused almost exclusively by reactivation of latent VZV and, in extremely rare circumstances, by HSV or CMV reactivation.5,12,13

Using electron microscopy and immunohistochemical methods Margolis et al. (1991) first demonstrated VZV in vitreous and retinal specimens of patients with PORN.5 The localisation of isolated viral capsids and VZV antigens in the outer retinal layers of retina in enucleated specimens coincided with the deep retinal necrosis seen in PORN.12 Subsequently, investigators have cultured VZV from chorioretinal biopsies and isolated VZV DNA using PCR from aqueous, vitreous and retinal specimens.12

Clinical presentation

Presenting symptoms of ARN are classically acute, unilateral loss of vision, hyperaemia, photophobia, floaters and pain. Fellow eye involvement will occur in 36% of cases, usually before six weeks from when the initial eye developed symptoms, but involvement can be delayed for an extended period of up to 20 years.7-9 The pain experienced may be worse with eye movements due to optic nerve and extraocular muscle involvement.9

Anterior segment signs include acute and significant inflammation. The inflammation may be fibrinous with keratic precipitates (granulomatous or non-granulomatous) and mild to moderately elevated intraocular pressure in 36.3% cases.7-9 Posterior synechiae may occur but iris atrophy is not typically seen which differentiates it from herpetic iridocyclitis. Diffuse scleritis may be present.9 Dilated fundus examination is crucially important and if not performed, the classically described ARN triad of vitritis, occlusive retinal arteritis and retinal necrosis would be missed.

The American Uveitis Society Diagnostic Criteria for ARN3

1. Clinical characteristics that must be seen: a) One or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders located in the peripheral retina (outside of the major temporal vascular arcades) b) Rapid progression (advancement of lesion border or development of new foci of necrosis) in the absence of antiviral therapy c) Circumferential spread d) Occlusive vasculopathy with arteriolar involvement e) Prominent inflammation of the vitreous and anterior chamber 2. Clinical characteristics that are supportive but not required for the diagnosis: a) Optic neuropathy or atrophy b) Scleritis c) Pain 3. The definition does not depend on the extent of the necrosis 4. The definition does not depend on the immunologic status of the host 5. The diagnosis is not influenced by isolation of any virus from ocular tissues or fluid The American Uveitis Society also recommended, in the event that the above diagnostic criteria are not met, that the terms previously used such as ‘limited or atypical ARN’ be replaced with the term ‘necrotising herpetic retinopathy’.3

The retinitis initially typically begins as numerous yellow white foci in the peripheral retina which then progress towards well-delineated, scalloped-edged plaques. When untreated these lesions coalesce and spread circumferentially within 5–10 days, advancing posteriorly. The posterior pole and macula are spared until late in the disease process.7,9,10 In general, ARN caused by VZV progresses more rapidly than HSV- ARN.9,10 Optic nerve involvement in ARN is quite common and can precede the onset of retinitis. Signs could include a papillitis, dyschromatopsia or relative afferent pupillary defect.9 The vasculitis in the acute stage is mainly arterial and occlusive in nature; however, phlebitis is also frequently observed. Retinal haemorrhages, if present, are not a prominent feature as in CMV retinitis.7-9

The extensive necrosis, which results in peripheral retinal atrophy and retinal breaks, as well as the vitreoretinal tractional bands (that result from the resolved vitritis), predispose to combined tractional-rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. The rate of these in the literature ranges from 50–75%.8,9

Presenting symptoms of PORN include sudden onset, usually unilateral loss of vision, or visual field loss. Importantly, unlike ARN, PORN is usually painless and asymptomatic.12 Patients reported previous cutaneous zoster infection in 67–78% of cases, depending on the study.13,14

Classically, intraocular inflammation is minimal or absent. Anterior chamber inflammation was seen in 38% of eyes and was usually mild.13 Most cases had 1+ cells. Keratic precipitates were only observed in 11% and were fine and nongranulomatous.13,14 Vitreous inflammation was only present in a quarter of patients and tended to be mild.13 Newer case series report even lower rates of inflammation.14

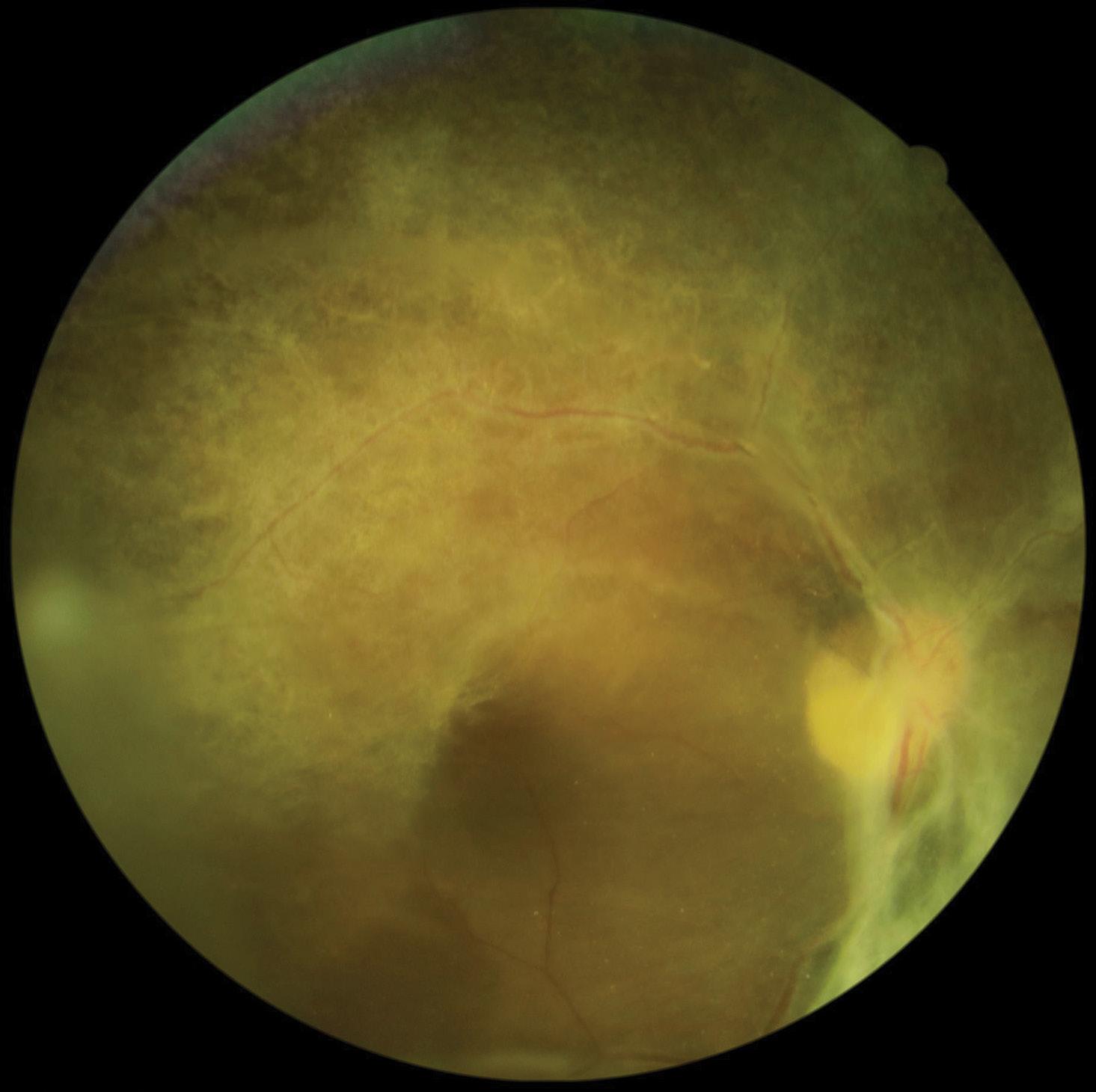

The retinitis is described as starting as multifocal, discrete lesions without granular borders arising in the outer retinal layers of the peripheral retina. These lesions progress and coalesce rapidly to involve the posterior pole early on, unlike ARN.12-14 Approximately a third of patients will have macular involvement at presentation. There is no consistent direction of disease spread13 (Figures 1 and 2).

Retinal vasculitis and haemorrhages are typically absent and this is an important distinguishing feature in PORN.12,13 PORN characteristically has perivascular sparing from retinitis which gives the fundus a ‘cracked mud’ appearance.12,13 Optic nerve involvement including disc swelling, hyperaemia and optic atrophy can occur, although less frequently than in ARN.13

Resolution of the retinitis in PORN results in multiple atrophic posterior retinal holes and breaks that predispose to rhegmatogenous retinal detachments which are reported to occur in 70% of affected eyes.12,13 The median time to retinal detachment is three weeks, usually occurring within the active necrotic phase, although retinal detachment can occur many months later during the inactive phase.13,14

Figure 1. A case of PORN in the right (above) and left (below) eyes before initiation of both systemic and intravitreal antiviral therapy. The widespread retinal necrosis and early posterior pole involvement is evident. A vitreous tap on the right eye which was no light perception on presentation revealed positive PCR for varicella zoster virus.

Investigations and work-up

Both ARN and PORN are clinical diagnoses. If the presentation is typical or if clinical suspicion is sufficiently high, then therapy is to be commenced immediately while waiting for confirmatory laboratory testing, usually PCR, which is the current gold standard.8,9,15

Figure 2. Fundus photographs of the right eye (above and below) of the same case after treatment with intravenous acyclovir and intravitreal ganciclovir treatment demonstrating widespread scarring

1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): PCR has largely supplanted all other historically performed diagnostic procedures. The sensitivity of PCR testing is as high as 79–100%.15

Multiplex PCR, a qualitative PCR test, can accurately detect multiple different types of minute viral nucleic acid fragments in only 90 minutes.15

Real-time PCR, a quantitative PCR test, is now readily available and can accurately quantify viral load allowing clinicians to monitor response to treatment.15 Studies have looked at initial viral loads and postulate that high viral loads may be linked to worse disease severity and poorer final visual outcomes.15,16

A few studies have been performed comparing diagnostic pick-up rates of aqueous sampling versus the gold standard vitreous sampling using PCR testing. Advantages of aqueous sampling via paracentesis is that it is easier, safer and more convenient. Apart from a single outlying study, the consensus is that there is no significant difference between sampling techniques.8,10,16

2. Retinochoroidal biopsy: In rare cases with a negative PCR in the presence of high clinical suspicion for a necrotising herpetic retinopathy, biopsy can be performed.10

3. Goldmann-Witmer coefficient: This is a type of indirect testing tool that compares the amount of intraocular antibody to the amount serum antibodies. It has largely fallen out of popular use.9

4. Fluorescein angiography: In ARN, although the quality may be limited by the overlying vitritis, angiography may demonstrate the occlusive vasculitis. Initial hypofluorescence and late staining may indicate choroidal involvement. Optic nerve involvement may also be demonstrated.10 In PORN, choroidal involvement may also be evident, and characteristic features are that of arteriolar narrowing and widespread retinal staining. The perivenous capillary network remains spared.12

5. B-scan ultrasonography: This is useful in ARN for detecting retinal detachment when view of the fundus is obscured by vitritis.7,8

6. Optical coherence tomography: Although not useful in the acute stage, later it may detect complications such as cystoid macular oedema, macular atrophy and epiretinal membranes.8,9

7. Laboratory and serum testing: Baseline full blood count, liver and kidney function testing are useful prior to initiation of systemic treatment and for dosing considerations. HIV status and CD4 lymphocyte count need to be obtained.10 It is important to exclude differentials such as syphilis, etc.8,10

Medical therapy Antivirals

Prompt initiation of a systemic antiviral agent is needed to treat the affected eye as well as protect the fellow eye. Systemic antivirals have been shown to reduce fellow eye involvement from 70% at two years down to 13%.9,10 High dose induction therapy is given either intravenously or orally for 10–14 days. Clinical stability should be seen approximately 48–72 hours after initiation although it may take up to 6–12 weeks for resolution of the inflammation. Maintenance therapy is given for a minimum of six months and is crucial as antiviral medication cannot eradicate herpetic viruses and recurrences and reactivations are common.7,8,10

ARN is traditionally treated with intravenous acyclovir induction followed by oral maintenance. New evidence suggests oral antiviral therapy, usually valacyclovir, reaches acceptable plasma drug levels and vitreous concentrations and can be used as an effective alternative induction modality.8,10 Oral induction is popular as it avoids hospitalisation and the subsequent costs incurred. No formal direct comparison between oral and intravenous treatment modalities has been done although there are a number of retrospective reviews which suggest that their outcomes are comparable and either may be used.10

Adjunctive intravitreal antivirals (foscarnet and ganciclovir) have been studied as part of the induction regimen to attain immediate therapeutic vitreous drug levels. This may reduce severe vision loss as well as diminish retinal detachment risk from 60% to 35%. Intravitreal antivirals are not to be used as monotherapy as this puts the fellow eye at risk.8,10

Acyclovir, famciclovir and valacyclovir constitute first-line therapy and demonstrate good activity against both VZV and HSV. They are competitive viral DNA polymerase inhibitors and are generally well tolerated in both intravenous and oral forms.8,10 The drugs are excreted renally and dose adjustments are required in geriatric and renal-failure patients. The most common reported side effects of these first-line antivirals are gastrointestinal disturbances, headaches and rash. Intravenous acyclovir can cause nephrotoxity or central nervous system disturbances.7,8,10

Generally accepted doses for induction and maintenance are given in Tables I and II. 10

ARN cases that respond poorly to acyclovir could be due to the HSV, or rarely drug-resistant VZV. Acyclovir resistant HSV is described in the literature in less than 1% of immunocompetent patients but in as high as 14% of immunocompromised cases.10 Acyclovirresistant VZV is uncommon and has rarely been described in the literature. Other reasons for first-line treatment failure are suboptimal dosing or misdiagnosed CMV which responds poorly to acyclovir.8,10

The antivirals ganciclovir, valganciclovir and foscarnet which serve as secondline treatment for CMV retinitis can also be used to treat acyclovir-resistant HSV and to a lesser extent VZV.8,10 Ganciclovir is available in oral, intravenous preparations, and off label as intravitreal therapy. Valganciclovir, an oral prodrug of ganciclovir, is a good alternative to parenteral ganciclovir.8,10 The main side effects of both drugs include bone marrow suppression and neutropaenia. Doses also require adjustment in renal patients.7,10 Foscarnet is only available as an intravenous formulation or as intravitreal therapy. Side effects include nephrotoxicity and hypocalcaemia.10 Additional adverse effects of intravitreal injection include endophthalmitis, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment.10

Initially the same acyclovir induction and maintenance regimen that yielded good outcomes in ARN was applied to treating PORN with appalling effect. Moreover, multiple reports exist of patients developing PORN while on acyclovir prophylaxis or treatment for cutaneous zoster infection.12,14 Various combinations of one or more systemic antiviral agents are usually used and may yield slightly better outcomes but no single agreed-upon treatment regimen exists.12 Bi-weekly adjunctive intravitreal antiviral injections have been shown to be beneficial.12,14 After initial induction therapy which can consist of two systemic antivirals (usually from the second-line group) as well as twice weekly intravitreal injections, long-term maintenance therapy (which may include systemic antivirals and intravitreal injections every two weeks) is required to protect against recurrences which are extremely common.12-14

Newer antivirals such as sorivudine, vadarabine and bromovinyldeoxyuridine (BVDU) have been proposed to possibly treat PORN but evidence is insufficient at this stage.12

Table I: First-line antivirals in the treatment of necrotising herpetic retinitis and recommended doses

Drug Induction Maintenance

Drug: Acyclovir Induction: 10 mg/kg IV 8 hrly 10–14 days Maintenance: 800 mg orally 5×/day

Drug: Valacyclovir Induction: 1 000–2 000 mg orally 3×/day Maintenance: 1 000 mg orally 3×/day

Drug: Famciclovir Induction: 500 mg orally 3×/day Maintenance: 500 mg orally 3×/day

Adjunctive medical therapy

Oral prednisone (0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day) started 1–2 days after the initiation of antiviral therapy has been recommended in the literature.7 The rationale is to treat the severe inflammatory response and optic neuropathy associated with ARN. Intravitreal dexamethasone or triamcinolone has been used and may decrease vitritis as well as improve final visual outcomes, but may worsen the retinal necrosis. Topical corticosteroids are also often utilised.7,10

Aspirin and other anticoagulants such as warfarin have been used as adjuvant in the management of ARN. This treatment is postulated to treat the hypercoagulable state, extensive occlusive vasculitis and ischaemic optic neuropathy. Strong evidence for their use and benefit is lacking and their safety should be carefully considered before use.10

Table II: Second-line antivirals in the treatment of necrotising herpetic retinitis and recommended doses

Drug: Foscarnet Induction: Intravitreal 2.4 mg/0.1 mL repeated 1–2×/week Intravenous 90 mg/kg IV 8 hrly

Drug: Ganciclovir Induction: Intravitreal 2 mg/0.1 mL repeated 1–2×/week Intravenous 5–10 mg/kg/day

Drug: Valganciclovir Induction: 900 mg orally 2×/day for 3 weeks Maintenance: 900 mg orally daily

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is an important adjunct in PORN treatment.12 Studies have reported a correlation in that patients who are already on HAART at time of presentation of PORN are less likely to develop retinal detachments.14 The degree of immune recovery required before discontinuing systemic antiviral maintenance therapy has not been established. Some authors consider a CD4 lymphocyte count of more than 100 cells/µL sufficient based on data from CMV-retinitis studies while others advocate for lifelong antiviral prophylaxis.12,14

Prophylactic laser retinopexy

The use of prophylactic laser in ARN was initially advocated for as several small retrospective comparative series demonstrated the apparent benefit and protection against retinal detachment. However, in these studies, laser was usually performed on eyes with better initial presenting visual acuities, less extensive retinitis and had clearer media to allow for laser retinopexy. The selection bias confounds the results and therefore no strong evidence currently exists to suggest there is any benefit to prophylactic laser retinopexy.8,10

In the few studies evaluating prophylactic laser retinopexy in PORN, laser was deemed non-beneficial in preventing retinal detachments.12,13

Surgical management

Large retrospective reviews have demonstrated no anatomic or visual benefit to early vitrectomy in either ARN or PORN.8,10 Retinal reattachment surgery is done through a standard three-port pars plana vitrectomy and the tamponade of choice is silicone oil. Successful anatomical reattachment in PORN is reported in 70–87% of cases.12,10 The decision to operate on a retinal detachment depends on the extent of retinal necrosis and whether the patient would derive any visual improvement. Other factors to consider are optic nerve involvement, the state of the fellow eye, as well as general patient fitness and life expectancy.12

Outcomes and prognosis

Visual outcomes in ARN are typically poor, although still better than PORN. Fortyeight per cent of affected eyes have a visual acuity worse than 20/200 at six months.10 The most common causes of visual loss are retinal detachment, chronic vitritis, cataract development, epiretinal membranes, macular ischaemia or oedema, and optic neuropathy.10,17

VZV-induced ARN carries a worse prognosis than those ARN cases caused by HSV.16 Only 32% of VZV-ARN and 67% of HSV-ARN eyes had a final visual acuity of greater than 0.5. VZV-ARN has been shown to have a 2.5 times greater risk to retinal detachments than HSV-ARN.8,10

Engstrom et al. (1994) were the first to report the devastating nature of PORN in which 67% of cases progressed to no light perception (NLP) vision within four weeks of onset.13 Newer studies using combination systemic antivirals with adjuvant intravitreal injections report less grim outcomes.12,14 Factors affecting final visual acuity are: extent of retinal necrosis and initial visual acuity at the time of starting therapy; development of a retinal detachment; and underlying immune status.12 Overall mortality rates in patients with PORN is high due to their significant underlying immunocompromise. Gore et al. (2012) reported 31% mortality in a South African population.14

Conclusion

The necrotising herpetic retinopathies are rare, potentially devastating ocular conditions. It is prudent to consider ARN as a possible differential in any patient presenting with an anterior uveitis or scleritis and always perform a dilated fundus exam on the first visit. Similarly, PORN should be on the differential when diagnosing retinitis in an immunocompromised patient.

PCR-based diagnostic tools are extremely useful and should certainly be used when available. Treatment consists of induction of systemic antiviral medication which can be either oral or intravenous with adjunctive intravitreal injections, followed by long-term maintenance. It is imperative to counsel patients regarding the guarded prognosis carried by these conditions.

References

1. Urayama, AY, Sasaki, T, Nishiyama, Y, et al. Unilateral acute uveitis with periarteritis and detachment. Japan J Ophthalmol. 1971;25:607-19.

2. Culbertson WW, Blumenkranz MS, Haines H, et al. The acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Part 2: histopathology and etiology. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1317-25.

3. Holland, GN. Standard diagnostic criteria for the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(5):663-67.

4. Forster DJ, Dugel PU, Frangieh GT, et al. Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(4):341-48.

5. Margolis, TP, Lowder, CY, Holland, GN, et al. Varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(2):119-31.

6. Guex-Crosier, Y, Rochat, C, Herbort, CP. Necrotizing herpetic retinopathies: A spectrum of herpes virus induced diseases determined by the immune state of the host. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1997;5(4):259-66.

7. Bonfioli AA, Eller AW. Acute retinal necrosis. In Seminars in ophthalmology 2005 Jan 1 (Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 155-60). Taylor & Francis.

8. Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ, Thorne JE, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute retinal necrosis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017 Mar 1;124(3):382-92.

9. Usui Y, Goto H. Overview and diagnosis of acute retinal necrosis syndrome. In Seminars in ophthalmology 2008 Jan 1 (Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 275-83). Taylor & Francis.

10. Powell B, Wang D, Llop S, et al. Management strategies of acute retinal necrosis: current perspectives. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2020;14:1931.

11. Young NJ, Bird AC. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62(9):581-90.

12. Austin RB. Progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome: a comprehensive review of its clinical presentation, relationship to immune system status, and management. Clin Eye Vis Care. 2000;12(3-4):119-29.

13. Engstrom RE, Holland GN, Margolis TP, et al. The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. A variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(9):1488-502.

14. Gore DM, Gore SK, Visser L. Progressive outer retinal necrosis: outcomes in the intravitreal era. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2012;6:700-706.

15. Sugita S, Ogawa M, Shimizu N, et al. Use of a comprehensive polymerase chain reaction system for diagnosis of ocular infectious diseases. Ophthalmology. 2013;9:1761-68.

16. Tran, THC. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of aqueous humour samples in necrotising retinitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(1):79-83.

17. Ittner EA, Bhakhri R, Newman T. Necrotising herpetic retinopathies: a review and progressive outer retinal necrosis case report. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2016;1:24-29.