10 minute read

Imiquimod pump takes the hassle out of dosing

Imiquimod pump takes the hassle out of dosing

Actinic keratoses (AK) are common in individuals with light skin – especially those with a history of cumulative sun exposure. AK lesions can disappear, persist or, rarely develop into non-melanoma skin cancer (cutaneous basal cell carcinoma [cBCC] 0.5%, or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma [cSCC] <1%).1,2

Arecent (2023) comprehensive and updated analysis found that the global prevalence of AK is ~14%. In tropical and temperate regions, the AK prevalence rate is ~18% and in subtropical regions it is ~2%. South Africa is divided into subtropical and temperate regions, which implies that the prevalence of AK is between 2% and 18%. Therefore, the potential number of people affected by AK in South Africa could range from ~1.2 million to ~10.8 million.3

Among individuals aged >60-years, the overall prevalence rate is 19%, whereas for those aged <60-years, it was 15%. Notably, in men, the overall prevalence rate is 24% with high heterogeneity, while in women, it is 14%.3

The development of AK is influenced by five key independent risk factors:4

Age

Gender

Phototypes I and II

Previous history of cutaneous neoplasms

Occupational sun exposure.

The history of previous skin neoplasms is particularly significant as it reflects individual genetic factors affecting sensitivity to UV radiation and chronic UV exposure. Assessing the impact of occupational sun exposure reveals a two-to-three times higher risk for AK in outdoor workers, with an increased risk for all cutaneous neoplasms (odd ratio [OR]: 3.45 for AK, 3.67 for cSCC, 3.32 for cBCC, and 1.97 for melanoma).4

Additional risk factors include episodes of painful sunburn before age 20 (OR = 1.21), lack of sunscreen use (OR = 1.81), and a positive family history of cutaneous neoplasms (OR = 1.85). Painful sunburn episodes before 20 years may initiate carcinogenesis, leading to p53 gene mutations and clonal keratinocytic expansion due to acute and chronic UV radiation exposure.4

Patients with chronic use of systemic immunosuppressive pharmacotherapy constitute a specific risk group for developing cutaneous neoplasias and dysplasias due to the carcinogenic effects of UV radiation.4

Clinical signs and symptoms

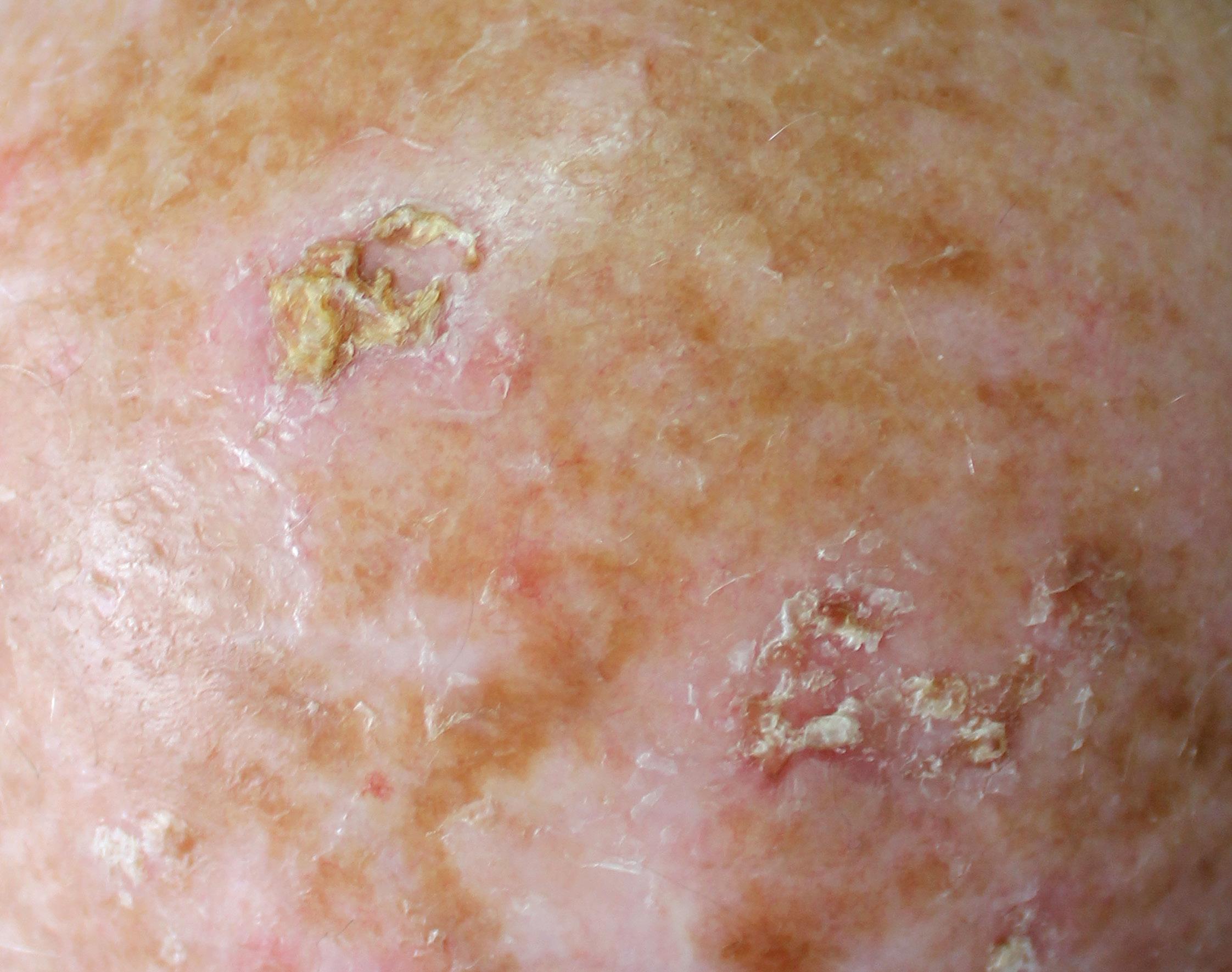

AK manifest as erythematous macules, papules, or plaques, typically exhibiting poorly defined borders and often covered by adherent dry scales. Palpation may prove more effective than visual inspection for accurate identification, and varying degrees of hyperkeratosis are observed.4

The lesions can appear as either singular or multiple entities, showcasing colours ranging from pink to erythematous or assuming a brownish hue, especially in the case of pigmented actinic keratoses. The degree of infiltration varies based on the intensity and extent of lesion dysplasia. While these lesions are largely asymptomatic, some patients may report discomfort, including sensations of burning, pain, bleeding, or pruritus.4

AK may take on various forms, exhibiting clinical variants including hyperkeratotic AK, non-hypertrophic AK, pigmented lichenoid AK, cutaneous horn, and actinic cheilitis. Each variant possesses distinct clinical and morphological characteristics, underscoring the importance of accurate recognition for proper management. This differentiation is crucial, as certain subtypes of actinic keratoses respond more effectively to specific therapeutic modalities.4

No pain, no gain

Treatment options for AK can be broadly categorised into lesion-directed and field-directed therapies. The prevailing notion associated with AK treatment is the ‘no pain, no gain’ approach, suggesting that effective treatment may entail some discomfort or side effects.5

Lesion-directed therapies target individual actinic keratoses, employing methods such as cryotherapy, curettage, or surgical excision. These approaches effectively address specific visible lesions. However, recurrence is more common than other methods.5

Conversely, field-directed therapies offer the advantage of treating multiple, widespread, and subclinical AK within an area of chronic sun damage. Examples include topical medications such as imiquimod, light-based therapies like photodynamic therapy (PDT), or laser resurfacing, aiming to treat the entire affected skin field. These treatments address both visible and subclinical lesions.5

In South Africa, imiquimod is approved for the topical treatment of superficial cBCC, and of external genital/perianal warts and clinically typical, non-hyperkeratotic, nonhypertrophic AK on the face or scalp in adult patients.6

Considerations when selecting a treatment strategy

Treatment strategies must be personalised, considering factors such as lesion characteristics, patient preferences, treatment availability, adherence, adverse effects tolerability, and cost. Urgent intervention is warranted in cases of numerous lesions, bleeding, pain, or rapid lesion growth to prevent potential complications.5

Patient communication about anticipated treatment adverse effects, including blistering, erosion, crusting, burning, discomfort, pain, pruritus, erythema, and oedema, is crucial. Clear instructions on post-treatment skin care and the expected healing process are essential.5

Safety, efficacy, cosmetic outcomes and recurrence

Stokfleth et al conducted a non-controlled interventional clinical study to assess the effectiveness of imiquimod in treating multiple, multiform AK. Patients exhibiting clinically typical and visible AK lesions on the head were subjected to a fourweek regimen of 5% imiquimod cream, administered three times per week, followed by a four-week treatment pause.7

In cases where lesions persisted, a second course of treatment was initiated. The primary outcome measure was the complete clearance rate, indicating the absence of clinically visible AK lesions in the treated area.7

Treatment with imiquimod resulted in an overall complete clearance rate of 40.5% after the first course of treatment and 68.9% after the entire treatment course. Remarkably, 85.4% of the 7 427 baseline lesions exhibited clearance. Patients with hyperkeratotic/hypertrophic lesions demonstrated comparable responses.7

Notably, local skin reactions were the most frequently reported adverse effects, prompting treatment discontinuation in only four patients. The severity of these local skin reactions emerged as a robust predictor of treatment outcomes.7

Adverse effects are dose-dependent and is attributed primarily to the direct immunomodulation effects of imiquimod on the skin. Recovery is achieved after discontinuation or a reduction in use. However, it should be noted that intense local reactions tend to result in better results for treatment.8

The findings of the study by Stokfleth et al suggest that patients with multiple, multiform AK on the head can be effectively and safely treated with topical imiquimod in routine clinical practice. Importantly, patient education on proper drug administration is crucial for ensuring treatment success.7

A study by Kawtchenko et al compared the efficacy and cosmetic outcomes of topically applied 5% imiquimod cream, 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) ointment, and cryosurgery for AK treatment. Patients underwent one or two courses of cryosurgery, topical 5-FU, or one or two courses of topical imiquimod. Results showed that imiquimod not only demonstrated superior initial clinical clearance (85%) compared to cryosurgery (68%) and 5-FU (96%), but sustained clearance at 12 months (73%) over cryosurgery (4%) and 5-FU (33%). Imiquimod also yielding the best cosmetic outcomes. The study suggests imiquimod as a first-line therapy for sustained AK treatment.9

Recurrence is common, and the healing duration varies, necessitating vigilant monitoring. In cases of treatment failure, further investigation is crucial. Reasons may include non-adherence, misdiagnosis, or, rarely, the potential for malignant transformation to cBCC or cSCC. 5

In a study led by Gollnick et al, the team assessed the prolonged (60 months) clinical effectiveness and safety of oncedaily application of imiquimod 5% cream, administered five times per week for six weeks, for treating superficial BCC. Interim results showed an initial clearance rate of 90% was observed 12 weeks posttreatment. At the 12-month follow-up period, ~79.4% of participants remained clinically clear.10

At the end of the study (60 months), Gollnick et al reported that the overall treatment success estimate for all treated patients at the end of follow-up was 77.9% (80.9% considering histology).11

Non-adherence to treatment a huge stumbling block

A recent study by Koch et al showed that 46.9% of patients living with AK are non-adherent and 30.9% were non-persistent. Non-adherence refers to a patient’s failure to follow the recommended treatment plan, including medication schedules or lifestyle changes. It indicates a deviation from the prescribed instructions, such as missing doses or not adhering to dietary recommendations. On the other hand, non-persistence refers to discontinuing the recommended treatment prematurely before completing the prescribed duration.12

Koch et al found that lack of information about the application time (leave-on time) of the medication play a big role in non-adherence. Patients independently adjusted the therapy’s duration and dosing frequency regardless of their physician’s instructions. Interestingly, patients who had a more extended pre-treatment consultation tended to adhere to the correct treatment regimen.12

Additionally, patients with lower clearance rates showed significantly less awareness of application times and treatment duration, suggesting a link between pre-treatment consultation, adherence to application, and treatment success.12

Notably, patients gave low ratings for items such as ‘occurrence of adverse events’ (2.7/10), ‘fear of adverse events’ (2.1/10), and ‘discontinuation of therapy due to adverse events’ (2.1/10), with no discernible differences between adherent and non-adherent patients. This suggests that concerns related to adverse events do not significantly impact treatment adherence.12

How to patients feel about treatment with imiquimod?

A multi-centre, open-label study used the Skin-dex-17 and Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) surveys to evaluate the impact of 5% imiquimod cream treatment on patientreported outcomes and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The study revealed no clinically relevant impact on HRQoL, despite a low baseline impairment in HRQoL observed in both surveys.13

In a non-randomised pilot study, imiquimod 5% and another therapy achieved higher median TSQM scores for effectiveness and global satisfaction than previous treatments. Imiquimod 5% received the highest satisfaction scores for side effects. Unlike some treatments with known resolution of local skin reactions by week three, imiquimod side effects typically peaked in the initial two weeks and resolved by weeks three to four post-therapy.14

In a comparative study with 5% imiquimod cream and PDT with MAL, patients reported comparable tolerance levels, though a higher percentage treated with PDT expressed greater satisfaction a month after treatment cessation. Nevertheless, a significant portion of imiquimod-treated patients (72%) preferred the same retreatment, emphasising patient preference for imiquimod.15

As noted by Caperton and Berman, patients tend to prefer self-administration of imiquimod treatment due to the perceived advantages of ease, convenience, privacy, and autonomy compared to modalities administered by physicians.16

Innovation to improve accuracy and convenience

Imiquimod is now offered in a distinctive storage and dispensing system, employing a pump mechanism, designed to enhance patient satisfaction. The advantages of this innovative pump system include:17

Dispensing a controlled and precise amount of cream with each application.

Offering a simple and convenient usage experience.

Minimising the occurrence of degradation during storage.

Userfriendly for all patients, including the elderly and those with limited agility.

Enhancing adherence to treatment.

Reducing excessive patient contact.

Minimising product waste and loss.

Providing a consistent dose, thereby improving efficacy.

Not interfering with the imiquimod application technique.

Overall, the pump system is a more accurate, effective, and user-friendly method for delivering imiquimod. It effectively addresses several drawbacks associated with traditional packaging, such as imprecise dosing, manual delivery, and product wastage. Additionally, the pump system is more compact and portable, facilitating easier storage and transportation.17

Conclusion

The global prevalence of AK, as highlighted in a recent comprehensive analysis, is ~14%. Understanding the risk factors, clinical manifestations, and effective treatment modalities is crucial for managing AK successfully.

Imiquimod, a topical treatment option, has demonstrated promising results in terms of efficacy, safety, and cosmetic outcomes. Studies have shown its effectiveness in treating multiple AK lesions, and its superior outcomes and cosmetic benefits compared to other therapies.

The introduction of an innovative pump system for imiquimod aims to further enhance patient satisfaction by providing controlled and precise dosing, userfriendliness for diverse patient groups, improved adherence, and minimized product waste. This advancement addresses existing challenges associated with traditional packaging and administration methods.

References are available on request. SF