6 minute read

Who Gave Thee This Authority? -

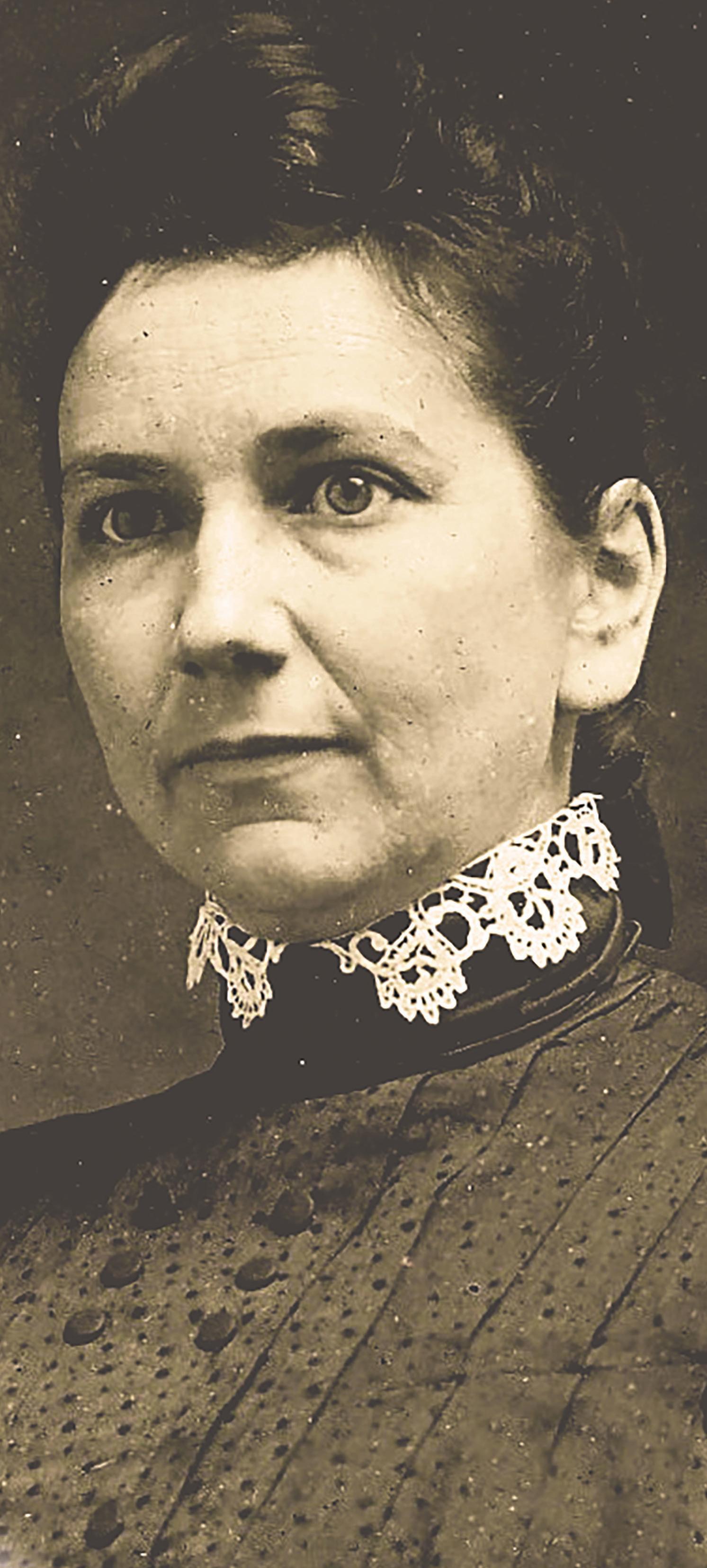

From the moment she embraced the preaching of the Word, Mary Lee Cagle knew she would have to defend her decision to claim the pulpit. In the 1890s, women preachers had to stand against the weight of social and religious tradition.

Holiness movement folklore eventually contained stories of preaching women who endured malicious gossip and slander. Amanda Coulson endured rabid opposition in Batavia, Arkansas, where it was rumored she had murdered her husband and abandoned her children. In truth, she was childless, and her husband, Rev. D. M. Coulson, was very much alive.1

The experience of other preaching women usually reflected simple prejudice. Dr. M. B. Harris, a deacon in the New Testament Church of Christ in Milan, Tennessee, discovered that his wife would not attend church when the scheduled preacher was female.2

Criticism of their roles generated solidarity among preaching women, and that solidarity strengthened the connectional bonds within early Nazarene parent bodies.

Apologies defending her right to preach became an early staple of the female preacher’s repertoire. Apologies took the form of sermons, pamphlets, and books.

Mary Cagle’s earliest apology was a sermon at Bluff Springs, Tennessee, in1896 titled “Women Preaching.” She dealt with critical scriptural texts used to oppose female leadership in the church, particularly those from the Pauline corpus. Cagle viewed these as restricted in their application and contrasted them with scriptures of different import, such as the Hebrew prophet Joel’s statement that “your sons and your daughters shall prophesy”—which the apostle Peter, in the most important sermon of his life, declared came to fruition on Pentecost.

Apologies defending her right to preach became an early staple of the female preacher’s repertoire.

Egalitarian instincts guided her expositions. To the passage in 1 Timothy which states, “I suffer not a woman to teach or usurp authority over a man,” she denied any reference to relationships in the church; rather, she regarded this as referring to relationships in the family. She extrapolated a further principle: a woman should not take authority over other women, either.3

Cagle’s last apologetic writing is contained in her autobiography, which begins with her childhood struggle over her call and concludes in the final chapter with the sermon “Woman’s Right to Preach.” Unlike autobiographies by male contemporaries, her anecdotal material is given a new dimension by the fact that it is told by a female preacher. Her stories of conversions and remarkable incidents in ministry implicitly verify her overarching claim that she, a woman, had been an effective minister called by God.4

The apologetic task fell on others too. The library of Donie and Balie Mitchum, both lay preachers, contained Phoebe Palmer’s Promise of the Father, a careful defense of woman’s right to preach, and Balie engaged in a spirited debate on the subject in the Milan Exchange, his local newspaper in western Tennessee.5

Donie had a sermon on “The Relation Woman Sustains to the New Testament Church.” She preached it in Bells, Tennessee, in May 1900 and relates: “I was lifted from all bad feelings and was lost in my subject and God.” The following year, with great effect, she used the sermon to overcome prejudice when she went to assist Rev. Ira Russell in a revival:

July 21st, 1901, Sunday. Some of the opposers to women preaching were objecting to me holding the service at Cade’s [chapel] last Sunday, quoting the text, “let the women keep silence in the churches etc.” trying to prove that Paul meant women [are] forbidden to preach or hold public services. I told Bro. Russell if he would allow me the privilege I would explain the meaning of that scripture to them & preach on that subject out there. So he made an appointment for me to deliver the talk today at eleven. Quite a number of us went out in a hack. I talked to a large congregation giving them the rights and authority for women preaching, or rather “The relation women sustain to the Church of Jesus Christ.” The Holy Ghost was poured out on us as I talked & gave them God’s word for my arguments. The congregation seemed to melt down & at the close of my discourse quite a number shook my hand (who once opposed the doctrine of women preaching) with tears in their eyes & said “I endorsed your sermon Sr. Mitchum, go on & preach & do all the good you can.”6

In Texas, Annie Fisher’s pamphlet Woman’s Right to Preach was a carefully crafted apology, while Emily Ellyson published Woman’s Sphere in Gospel Service. She was later ordained during the Second General Assembly, along with R. T. Williams.

The apogee came with Fannie McDowell Hunter’s Women Preachers (1905), published in Dallas, Texas. Hunter laid out arguments from scripture in the first fifty pages. The second half consisted of the call and service narratives of nine women, including Hunter, Cagle, and Mitchum. Other writers included Johnny Jernigan (later a co-founder of Bethany, Oklahoma), and Lillian Pool, the first Nazarene missionary in Japan.7

On the book’s paper cover, under the title, appear these words: “Who gave thee authority?”

Given their Wesleyan-holiness faith, these women had to say with the apostle: “Woe is me if I preach not the gospel.”

Dr. Stan Ingersol, Ph.D., is a church historian and former manager of the Nazarene Archives.

1 C. B. Jernigan, Pioneer Days of the Holiness Movement in the Southwest, pp. 33-

2 Donie Mitchum’s Journal, p. 76. Copy in the Nazarene Archives.

3 “Women Preaching,” a MS inscribed: “Sr. Harris preached at Bluff Springs, Oct. 4th, 1896;” in the Donie Adams Mitchum Collection. Mary Lee Cagle was known as Mary Lee Harris at the time she began her ministry.

4 Mary Lee Cagle, Life and Work of Mary Lee Cagle (1928). Her sermon is on pp. 160-176.

5 The Mitchum copy of Phoebe Palmer’s classic work on female ministry is in the Countess Hurd Collection at the library of Trevecca Nazarene University, Nashville, Tennessee. On the newspaper controversy over female ministry, see “As To Women Preachers” in the Milan Exchange (Mar. 27, 1897):5, and “Answers for ‘Sub Rosa’,” ibid.; (Apr. 3, 1897): 5.

6 Donie Mitchum’s Journal, pp. 141, 177-178.

7 Fannie McDowell Hunter, Women Preachers (Dallas: Berachah Press, 1905).