3 minute read

WINGS TO FLY An Interview with Isha & Salonee Sarnaik

Amy Chapple

Advertisement

HO4C produces high quality, safe and locally sourced and manufactured hats to meet all PPE requirements. Amy believes PPE should not only be about personal safety, but also respecting our People, Place of work and the Environment:

⋅Place specific, contextual, respectful of Traditional owner lands, customs and heritage ⋅ People informed, aware and notified to “inspect, replace and recycle” (within 3 years) ⋅ Environment preservation, landfill reduction and HO4C recycling program HO4C is committed to reducing landfill and believe product stewardship, corporate social responsibility and supporting a circular economy. Construction and demolition waste account for 44% of all landfill waste. In 2021, global hard hat sales totalled $6.1b (AUD)*, with $35 the average price per helmet with a company logo. Market predictions have this set to increase to $11.3b AUD 2030 (Grandview Research 2021).

With a maximum safety lifespan of three years that’s a lot of helmets going to landfill. Amy is hoping HO4C can address these safety and environmental issues.

“Buy Local” and “Close the Gap” policies ensure HO4C source Australian made products and supports AIPP committed suppliers and artists. This is not about taking, it’s about giving back, to communities, to educating future generations, to the environment.

HO4C is exploring other avenues to raise awareness of safety, promoting charities, emerging Australian artists from non-indigenous backgrounds, a “Lids 4 Kids” school program providing the opportunity to “paint their own Lid”. The ultimate goal is to develop the technology to make a new HO4C hat from recycled HO4C hats.

HO4C hats not only stand out for safety, they are the voice to stand up for Change; reinterpreting traditional PPE acknowledging the importance of People, our Place of work and the Environment.

Let’s collectively “take our hats off” for our people, our planet and for change.

For further information about Hats Off 4 Change, contact Amy Chapple E: amy@hatsoff4change.com M: 0450 587 252

MENTAL HEALTH & PREVENTION OF SUICIDE IDEATION

Among Female Workers Should Be an Industry Priority

The culture of the construction industry is dominated by traditionally held masculine ideologies such as stigma against seeking help for the risk of suicide and mental health problems. Construction workers are known to be at a greater risk of suicide than other occupational groups in Australia. The inability to balance work and personal needs can negatively influence wellbeing. Professor Sarah Payne working with other researchers highlights that the effects of working and living conditions on suicide may vary depending on gender. Research notes that female workers are more likely than male workers to report elevated rates of work-related stress and psychological injury arising from the unique challenges they face in the construction industry. As reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), rates of suicide attempt and self-injury are higher for females than males. In 2019–2020, females accounted for almost two-thirds (63%) of intentional selfharm hospitalisations in Australia. According to AIHW, this may be partly due to differences between the methods used by males and females—with males tending to use more lethal methods than females.

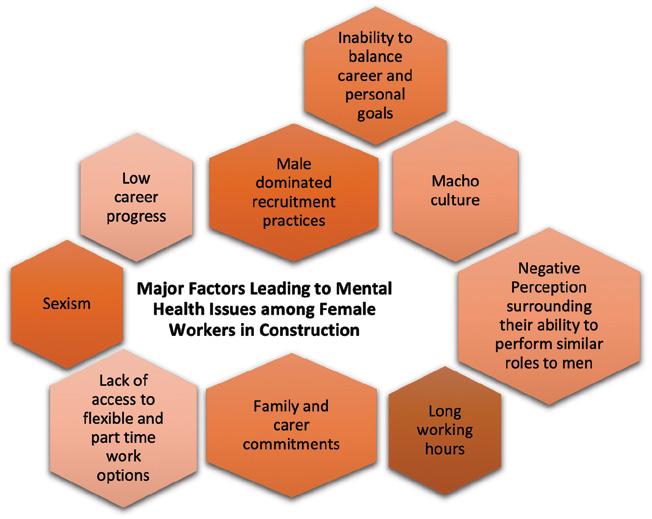

Women Building Australia reports that in 2020, female workers accounted for 14% of the workforce in the building and construction industry in Australia: an increase from 11% in 2019. Although considerable effort has been made to attract women to the construction industry, they face many unfavourable conditions. Dr Adedeji Afolabi and a group researchers indicate that the major issues faced by female workers in construction industry include long working hours, family and carer commitments, lack of access to flexible and part-time work options, male dominated recruitment practices and the negative perception surrounding their ability to perform similar roles to men. In addition, antifeminine characteristics in the construction workplace persist, including a macho culture, sexism, difficult conditions for balancing career and personal goals, intolerable working conditions, low career progress and expectations of mimicking male aggressive behaviour. In addition, the demanding work environment in construction has considerable potential to have a negative effect on every workers’ non-work lives. The Women in Construction Strategy of the Victorian Government also notes many of these factors as negatively affecting the physical and mental health of women in construction.

Dr Jacqueline H Watts indicates that high levels of depression, anxiety, stress and burnout among construction workers are driven by construction workplace characteristics such as the conflict-ridden, ‘dog-eat-dog’ work environment and the culture of blame. The effects of these