10 minute read

Inside: Raise the age of criminal responsibilit y

Image courtesy of Change the Record.

Every day across Australia, children as young as 10 can be arrested by police, taken before a court and locked in detention.

Advertisement

In the space of just one year, approximately 600 children between the ages of 10 and 13 were locked up and held in detention, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, who are disproportionately impacted, make up around 65 percent of these young people in prisons. Experts say that children who are arrested before the age of 14 are three times more likely to commit offences as adults.

A recent national push to raise the age stalled when federal, state and territory attorneys-general agreed that more work needs to be done to find alternatives to deal with young offenders. “Change the Record developed a blueprint for changing the record on the disproportionate imprisonment rates and rates of violence experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people back in 2015, and this included dealing with young people at risk of incarceration,” said Cheryl Axleby, Co-Chair of the Aboriginal body, CEO of the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement and Co-Chair of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services, a group for all legal bodies to come together three times a year, driving change on national justice issues. “We recommended changes for the Government to take on board back then. We need real leadership in this area. Black Lives Matter shone a light on Aboriginal incarceration – it opened people’s eyes that this is happening in Australia. But there have still been, I think, five incarnations since June. If there’s such an overrepresentation why isn’t funding changed to meet that overrepresentation, rather than being based only on our population. And nothing has changed for young people. The brain development of children in understanding the consequences for their actions is just not there at this young age but we still treat them like adults. We have a real punitive, colonial mindset when it comes to crimilisation in this country.” Change the Record’s blueprint for change specifies that punitive approaches to offending youth fail to acknowledge that young people are still developing and that exposure to youth detention substantially increases the likelihood of crime as an adult.

It recommends focusing on solutions that offer positive reinforcement and support instead, and suggests policy changes such as increasing the age of criminal responsibility and ensuring the presumption of legal incapacity continues to apply up to age 14; ensuring legislation mandating detention should be used only as a measure of last resort up until age 17; ensuring that legislation in each jurisdiction that dictates bail considerations and presumptions presumes favour of bail for young people; support for the development of specialist youth courts and ensuring exclusion from school is a last resort to help children focus and succeed in their studies.

Others vocal in this area agree that instead of the first response being to lock up young offenders for the ‘protection’ of both the community and the child, we should focus on early prevention instead, followed closely by preventive interventions built around keeping children in the community, with family. This response recognises that children are going through significant growth and development in their formative pre and early teen years and forcing them though criminal legal proceedings when they should be in school can seriously affect their ongoing health, wellbeing and future. The Raise the Age national campaign states that when a child between 10 and 13 is alleged to have caused harm to another, it’s a sign that something has gone wrong in that child’s life: “Violent actions or behaviour in young children are often directly linked to experiences of trauma, neglect, and harm or unaddressed mental or physical health problems. Rather than criminalise trauma, it is the responsibility of our governments to provide that child with the services needed to address the underlying causes of their behaviour and to set them onto a better path. The worst place for a child to be is in prison.” Specialists in this area include the Hon Dr Robyn Layton AO QC, a former South Australian Supreme Court Judge whose own interest began when she authored the South Australian Child Protection Review in 2003, which has since become known as the “Layton Report”. “I believe the minimum age should be what is recommended by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, which in 2019 said the minimum age should be 14. The statistics show that very young offenders keep on repeating and it becomes cyclical if we keep sending them to detention. Raising the age to 14 fits in with their cognitive capacity and capability; children under that age are really not able to reflect on what they are doing, to understand the nature and quality of their actions and be able to understand consequences,” said Dr Layton. “In Japan, Portugal and Spain the minimum age is 16; in Belgium it’s 18; Scandinavian countries and Iceland, 15; Austria, Germany and other Eastern European countries, 14 and in New Zealand it’s 14, with the exception of murder and manslaughter which is 10. The ACT recently became the first jurisdiction to endorse raising the criminal age to 14 and there’s no reason the other states and territories couldn’t do that.”

Dr Layton has spent the better part of 20 years researching the issue, advocating for better ways of dealing with offenders in this age group and, in particular, researching Aboriginal statistics and involving Aboriginal People in what the responses should be.

“We have tended to dictate as a white community how Aboriginal People ought to deal with the situation, even bearing in mind the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in detention. But the new Closing the Gap agreement indicates that there’s a groundswell by Aboriginal People to make sure their voices are heard.

“One of the new Closing the Gap targets announced at the end of July is the reduction of the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people (aged 10–17 years) in detention by at least 30 percent by 2031.”

Although she’s only seen incarceration rates going up over her years of work in this area, including for youth, Dr Layton believes these new targets, and initiatives at the community level by justice reinvestment programs and Aboriginal involvement being key to drive better outcomes.

A Patron of Junction Australia, Dr Layton supports their work in the area, and is also working with the Tiraapendi Wodli group in Port Adelaide, which is driven by Aboriginal leaders and taking a wholistic approach to try to stop incarceration of children.

“The approach they take is to keep children and young people engaged in their community and staying with family, so they have various programs to engage students to keep up with their schooling; men’s groups to encourage men be more connected with their children; a family connection group for families who are having problems so they can work with mentors and have various services brought in to ensure they are best supported to have their children stay with them, in community.”

Dr Layton urges people to write to their local members, particularly senior figures such as the Premier and the AttorneyGeneral to show that the community agrees with raising the age and thinks that children under 14 should not be held criminally responsible for their acts.

“The sooner we do it, the better it will be. Keeping children out of detention is primary; they’re the most vulnerable members of our community and locking them in detention is not a good way to let them know that what they are doing is wrong.”

The Honourable Dr Robyn Layton AO QC.

From 12-year-old documentar y subject to youth detention activist

Last year was a big year for 12-yearold Dujuan Hoosen, who’s from Alice Springs and Borroloola. First, he was the subject of a new documentary, In My Blood it Runs, about the challenges he faced in school and on the streets of Alice Springs.

Then, he found himself in Northern Territory Parliament, urging the Government to raise the age of criminal responsibility.

This led to him becoming the youngest person ever to address the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland, on behalf of the Human Rights Law Centre, where his message was simple: “I want adults to stop putting 10-year-old kids in jail.”

The young Arrernte and Garrwa boy himself avoided youth detention at the age of 10 when he started skipping school and found himself in trouble with police. An angangkere (healer) who speaks three languages, Hoosen still felt like a failure in the Western school system, where he was getting bad marks. In his speech to the NT Government read aloud by Labor backbencher Chansey Paech, Hoosen told Parliament to remember him “when you are making big laws about us”.

He wrote about how confused and disengaged he felt in school, where “history is for white people”.

“Let us speak our own languages in school and learn about what makes us strong,” he said.

“I think this would have helped me from getting into trouble and getting locked up or taken away from welfare.”

Dujuan appeared before the United Nations Human Rights Council in September 2019 and still, no changes have been made to laws around the age of criminal responsibility in the NT, SA or anywhere else in Australia, except for the ACT whose Legislative Assembly voted in August to raise the age to 14, making it the first Australian jurisdiction agreeing to bring its laws into line with United Nations standards.

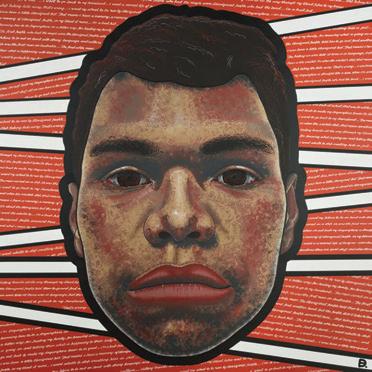

Dujuan Hoosen painted by Blak Douglas, a finalist in this year’s Archibald Prize.

Freeing the Aboriginal flag

When will Aboriginal people be able to freely use the Aboriginal flag again? Originally designed for the land rights movement in 1971, the Aboriginal flag has come to represent Aboriginal People Australia-wide since being adopted as an official ‘Flag of Australia’ in July 1995. But when Harold Thomas, a Luritja artist who designed the flag and holds its copyright, granted non-Indigenous company WAM Clothing the exclusive worldwide licence to use the design on clothing, physical and digital media in November 2018, organisations and companies using the flag on merchandise began being served cease and desist letters. This included both the AFL and NRL ahead of their Indigenous rounds, with both making the decision not to enter into an agreement with WAM Clothing to continue using the flag. WAM Clothing is owned by Ben Wooster, who used to run a now defunct Queensland art gallery called Birubi Art, which was fined $2.3 million in 2018 by a Federal Court for selling fake Aboriginal artwork made in Indonesia. Mr Wooster has since admitted in the September Senate inquiry that WAM Clothing products are also produced and printed in Bali.

Indigenous Australians Minister Ken Wyatt says the Federal Government is in conversation with Mr Thomas, who has held the copyright of the flag since 1997, and is attempting to broker a deal around its use.

A Senate committee chaired by Labor senator Malarndirri McCarthy has been established to investigate the copyright and licensing arrangements and look at options available to allow the design to be freely used by all Australians.

“It is a delicate and sensitive matter, and the Government respects the copyright of Mr Thomas and the interests of all parties,” a spokesperson for the minister told the ABC.

The Free the Flag movement has gained the support of some of Australia’s biggest Indigenous sporting stars such as Nova Peris, Michael Long and Eddie Betts, and every AFL club has now joined many Australians in signing the #FreetheFlag campaign.

The consensus of the Senate inquiry is that the flag should be controlled by an Aboriginal body in the future.

Above left: The Aboriginal flag flies proudly in the background of the recent Black Lives Matter protest. Above right: A protester at the recent Black Lives Matter protest holds a sign with the Aboriginal flag painted on it.

Flinders Ranges Aboriginal Corporation under police investigation

Adnyamathanha Traditional Lands Association (ATLA) has been under special administration since March this year, and SA Police recently confirmed it will remain that way while its governance and financial record-keeping is investigated. ATLA is the peak body for all matters relating to Native Title, land, culture, heritage and language for the Adnyamathanha People of the Flinders Rangers. It has roughly 850 members and receives royalties from mining operations in the area. under special administration in March, which has since been extended twice while the Sydney-based administrators try to work out the related transactions and entitles.

“The special administrators have uncovered an intricate network of related entities and interests within the ATLA corporate structure,” ORIC registrar Selwyn Button told the ABC. “The lack of record keeping has made it difficult for the special administrators to determine why some of these entities were created or even how they came to be. It’s unclear if members even knew of the existence of some entities.