9 minute read

FEATURES

Photo of Grand Chief Dr. Wilton Littlechild speaking at the 2018 Indigenous Peoples’ Justice Conference

How a national Indigenous justice strategy could implement

Advertisement

Cree best practices

by Patrick Quinn

Photos by Catherine Orr, Provided by the DOJCS

The Canadian government has promised a national justice strategy to address the systemic discrimination and disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous and Black peoples. While it’s still unclear when this strategy will arrive, Justice Minister David Lametti has said the new approaches will advance Indigenous-led solutions with “true partnership”.

Although Indigenous peoples represent about 5% of the Canadian population, 31.5% of federally incarcerated males and 42% of females are from Indigenous communities. They are subject to greater use of force, serve longer sentences, self-harm more frequently and have far higher recidivism rates.

“I’m hoping the government goes bold and recognizes the efforts of various governments have not yielded any significant reduction in the overrepresentation,” said the Correctional Investigator of Canada, Ivan Zinger. “Ultimately, alternatives to incarcerations and shifting corrections to empower Indigenous communities will yield a much better criminal justice system.”

Zinger’s office has made numerous recommendations over the years that he says have been dismissed by the government. But they have been picked up by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and other Indigenous inquiries. These include shifting substantial resources to transfer care, custody and supervision to Indigenous communities.

“The best thing that could happen is to reallocate significant funding from corrections to fund Indigenous communities so they can operate healing lodges and halfway houses,” Zinger told the Nation. “There is at least a great deal of consensus in what needs to be done. It’s not so much a strategy we need but action with deliverables and time frames.”

While Lametti introduced amendments to remove mandatory minimum penalties and expand alternatives to prison sentences in February, Zinger is skeptical they will result in much difference. He similarly believes “Gladue components” – based on the 1999 Supreme Court ruling that decreed sentencing be tailored to Indigenous social history – have not delivered the desired changes.

“Gladue is a bit of a band-aid,” asserted Zinger. “It was supposed to be temporary while the government brought justice in Canadian society. Gladue in perpetuity equates our own failure as a society. More of the same is not required here.”

All of Zinger’s office’s investigations into the justice system reveal disproportionate impacts. His most recent report showed federal prisons were hit twice as hard by the pandemic’s second wave, with Indigenous inmates accounting for 60% of those testing positive.

While the pandemic has had an inordinate impact on Indigenous peoples, its disruption to society has also been a catalyst for positive changes in the justice system. Travel restrictions have resulted in 47% fewer people held in remand custody while waiting for trials, with no related increase in crime.

“During Covid, we stopped incarcerating everyone until their court date,” said Donald Nicholls, the Cree Nation’s director of Justice and Correctional Services. “We said we don’t need people travelling, so why don’t we review who should actually go

into custody and who should remain in the community?”

Transporting Indigenous individuals from their remote communities to preventative custody is particularly traumatic and costly, often involving several transfers between provincial institutions and disconnecting them from family.

Nicholls believes the pandemic has enabled many changes that would not have happened otherwise, creating a more efficient and effective justice system. Trials are regularly held by video conference using a system built over a decade ago that allows them to connect with any courtroom in Quebec.

“With video conferencing, there were less hardships on the family,” Nicholls told the Nation. “We didn’t bring in people who would cause anxiety in the community. We started putting up

- Donald Nicholls (Pictured Right), the director of Justice and Correctional Services

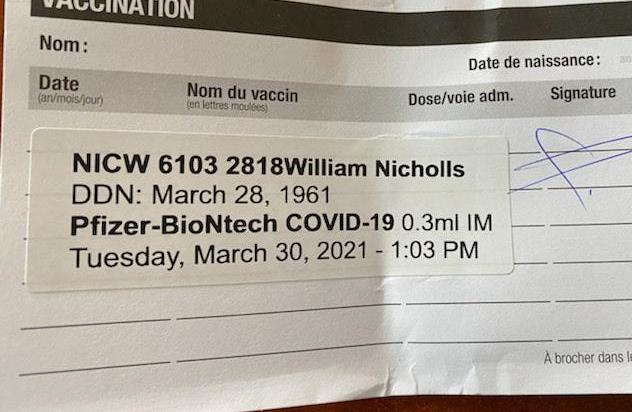

We all want to know more about COVID-19 vaccination

COVID-19 vaccination in Québec began in December 2020 as part of a massive efort to prevent serious complications and deaths related to COVID-19, and stop the virus from spreading. Through vaccination, we hope to protect our healthcare system and allow things to return to normal.

A VACCINATION OVERVIEW

Why get vaccinated at all?

There are many reasons to get vaccinated (all of them good), including protecting ourselves from health complications and the dangers stemming from infectious diseases, as well as making sure they don’t resurface.

How efective is vaccination?

Vaccination is one of medicine’s greatest success stories and the cornerstone of an efcient healthcare system. That said, as with any medication, no vaccine is 100% efective. The efcacy of a vaccine depends on several factors, including:

The age of the person being vaccinated Their physical condition and/or state of health, such as a weakened immune system

THE IMPACT OF VACCINES AT A GLANCE

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that vaccination helps prevent over 2 million deaths every year, worldwide. Since the introduction of vaccination programs in Canada in 1920, polio has been wiped out across the country and several other illnesses (such as diphtheria, tetanus and rubella) have virtually disappeared. Smallpox has been eradicated throughout the world. The main bacteria responsible for bacterial meningitis in children–Haemophilus influenzae type B–has become much rarer. Hepatitis B has for all intents and purposes disappeared in young people, due to their having been vaccinated in childhood.

COVID-19 VACCINES

Are the vaccines safe?

Definitely. COVID-19 vaccines have been tested for quality and efcacy on a large scale and passed all necessary analysis before being approved for public use.

All required steps in the vaccine approval process were stringently followed, some simultaneously, which explains why the process went so fast. Health Canada always conducts an extensive investigation of vaccines before approving and releasing them, paying particular attention to evaluating their safety and efcacy.

Who should be vaccinated against COVID-19?

We aim to vaccinate the entire population against COVID-19. However, stocks are limited for now, which is why people from groups with a higher risk of developing complications if they are infected will be vaccinated first.

Can we stop applying sanitary measures once the vaccine has been administered?

No. Several months will have to go by before a sufcient percentage of the population is vaccinated and protected. The beginning of the vaccination campaign does not signal the end of the need for health measures. Two-metre physical distancing, wearing a mask or face covering, and frequent hand-washing are all important habits to maintain until the public health authorities say otherwise.

On what basis are priority groups determined?

The vaccine will first be given to people who are at higher risk of developing complications or dying from COVID-19, in particular vulnerable individuals and people with a significant loss of autonomy who live in a CHSLD, healthcare providers who work with them, people who live in private seniors’ homes, and people 70 years of age and older.

As vaccine availability increases in Canada, more groups will be added to the list.

Order of priority for COVID-19 vaccination

1 Vulnerable people and people with a significant loss of autonomy who live in residential and long-term care centres (CHSLDs) or in intermediate and family-type resources (RI-RTFs). 2 Workers in the health and social services network who have contact with users. 3 Autonomous or semi-autonomous people who live in private seniors’ homes (RPAs) or in certain closed residential facilities for older adults. 4 Isolated and remote communities. 5 Everyone at least 80 years of age. 6 People aged 70–79. 7 People aged 60–69. 8 Adults under the age of 60 with a chronic disease or health issue that increases the risk of complications from COVID-19. 9 Adults under the age of 60 with no chronic disease or healthcare issues that increase the risk of complications but who provide essential services and have contact with users. 10 Everyone else in the general population at least 16 years of age.

Can I catch COVID-19 even after I get vaccinated?

The vaccines used can’t cause COVID-19 because they don’t contain the SARS-CoV-2 virus that’s responsible for the disease. However, people who come into contact with the virus in the days leading up to their vaccination or in the 14 days following it could still develop COVID-19.

Is COVID-19 vaccination mandatory?

No. Vaccination is not mandatory here in Québec. However, COVID-19 vaccination is highly recommended.

Is vaccination free of charge?

The COVID-19 vaccine is free. It is only administered under the Québec Immunization Program and is not available from private sources.

Do I need to be vaccinated if I already had COVID-19?

YES. Vaccination is indicated for everyone who was diagnosed with COVID-19 in order to ensure their long-term protection.

Québec.ca/COVIDvaccine 1 877 644-4545

plexiglass in the courtroom, bought 20,000 masks, and implemented air purifiers in the front area.”

The Cree Nation’s Justice Department was established in 2008 to respect both the federal and provincial judicial regimes while creating services and programs that honour the Cree culture. With an emphasis on traditional values, restorative treatment and addressing the root causes of crime, it’s a system demonstrated to create safer communities and more harmonious relationships.

“We want the Cree values to be reflected so people know there will be an understanding of who they are,” said Nicholls. “If you send someone from the Cree Nation off to detention, they may or may not get a reduced sentence with Gladue and certainly there’s no programming offered in the Cree language other than what we bring in. That’s why Dr. Zinger would say the best programming is in the community.”

The Justice Department supports Crees in detention facilities by sending Elders and specialists to do traditional counselling and cultural workshops. While there may be access to programs like Pathways in the federal system, an Elder-driven healing initiative based on the teachings of the Medicine Wheel, they send interpreters to ensure the lessons are understood.

At a recent international conference, Nicholls highlighted the importance of translation services in the justice system. His team has been developing a glossary of legal terms that clearly explain in Cree the concepts that are being discussed in courtrooms, corrections and public health.

“We’ve developed this terminology in all the dialects, so people clearly understand what is happening, because the consequences are big,” Nicholls explained. “In court sessions across the country, sometimes the translation doesn’t always reflect what’s being discussed, sometimes it’s paraphrased or there’s a limitation of words.”

A national justice strategy would do well to emulate Cree best practices such as conflict resolution training for all employees, land-based programming and local tribunals. Through agreements with the court, over 100 cases annually are sent back to the communities to determine how the offender can repair the harm that may have been caused.

“Every year we give the local tribunals money to develop community-based initiatives, suicide prevention weeks, healing lodges,” said Nicholls. “They consider wilderness therapy six times as effective as institutional therapy. We take them out and show this is a healthy relationship with yourself and with others.”

Emerging initiatives include supervised living communities, anger and addictions management programming, employability and community connections. A new land-based camp will also be added to Mistissini’s regional youth healing centre this summer.

“A few years ago, the director of healing services asked to do this program reconnecting youth with their families for six weeks,” shared Nicholls. “We made them build their own shelter as a family. Each day there were activities with no distractions out on the land. The results were incredible..”