5 minute read

Protect

Western Sydney’s Last Great Landscape?

BY LISA HARROLD, PRESIDENT OF MULGOA VALLEY LANDCARE GROUP

Sandwiched between rapidly-growing Penrith and the new Aerotropolis lies a small oasis. Mulgoa Valley is a rare landscape in the Sydney basin: rolling green hills, important ecological communities and significant heritage properties. But pressure is mounting to unwind the protections that ensure the valley remains a special place.

Any ‘last of its kind’ is precious. And over the past 200 years, Mulgoa Valley has become the last major landscape on Sydney’s Cumberland Plain that remains relatively free from unsympathetic development. Situated on the western edge of the Plain, the valley has long been recognised as unique. It marks an important boundary between the Darug peoples from the plains and the Gundungurra from the mountains. The Mulgowie Clan of the Darug nation are the traditional custodians of the valley, and it still holds many of their secrets.

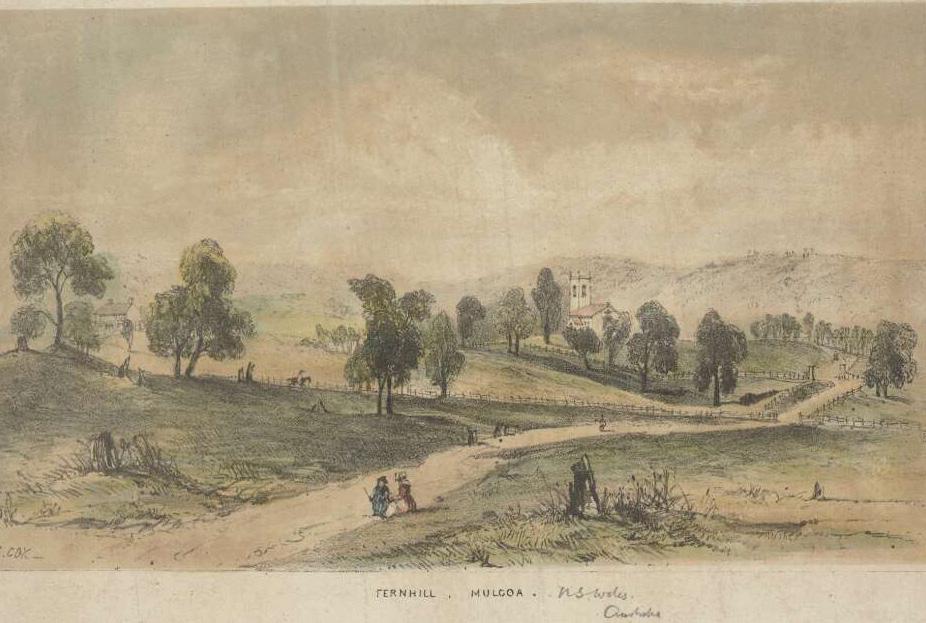

Mulgoa Valley is home to many places of significant natural and heritage value. The Mulgoa Nature Reserve and the Mulgoa section of the Blue Mountains National Park contain important communities of plants, animals and woodland native to the Cumberland Plain. The valley provides habitat critical to scarlet, flame and rose robins during their annual migration from the Blue Mountains to the Cumberland Plain each winter. The endangered regent honeyeater and swift parrot also take refuge there. Ten properties within Mulgoa Valley support wildlife conservation through Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements. There is also a rich tapestry of colonial heritage properties in the valley. Six are listed on the NSW State Heritage Register, including the exquisite Fernhill Estate. The archaeological remains of Regentville, a famous country house built by Sir John Jamison in the early 1800s, lie within Mulgoa Nature Reserve. Roughly one-quarter of Mulgoa Valley is preserved in perpetuity for its heritage and conservation values.

Below Mulgoa landscape (photo by P. Barkley).

Opposite from top Mulgoa landscape (photo by P. Barkley); Scarlet Robin (photo via Alamy); Lithograph of Fernhill by C. Cox, looking towards St Thomas Church (photo via nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an8421802).

But is Mulgoa really protected? Unfortunately, these arrangements do not automatically provide protection from unsympathetic development. Fernhill, for example, has two heritage listings – one for the 1842 Greek Revival house and one for its rural colonial landscape – as well as Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements covering hundreds of hectares. Yet, in recent years, the property has been subject to multiple Development Applications for subdivisions of up to 250 housing blocks. Rookwood Cemeteries Trust wanted to put the largest cemetery in the southern hemisphere there. Thanks to vocal and hard-fought campaigns by the Mulgoa community, these applications failed.

And even though Fernhill is now in public ownership under the Western Sydney Parklands Trust (WSPT), it is still being “investigated for commercial and residential leasing opportunities”, according to the draft Fernhill Plan of

From left Nepean River as seen from the Rock Lookout, Mulgoa (photo by Anne Cutajar); Fernhill, Mulgoa (photo via fernhillestate.cve.io).

Management. The WSPT is also investigating whether the Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements should be ‘undone’ in order to manage public access to the estate.

Weak and weakening planning control The critical problem is the lack of effective planning control. The key policy that initially helped protect the Mulgoa Valley no longer exists. The Sydney Regional Environmental Plan (SREP) No. 13 was a visionary instrument, whose foreword read: “development should not be allowed to significantly change the character of Mulgoa Valley nor threaten its ecological and heritage resources. The valley can play an important role in conservation, tourism and recreation in Western Sydney” (Bob Carr, 1987). SREP 13 played a pivotal role in conserving the scenic and rural landscapes that we enjoy in Mulgoa today.

However, about a decade ago, SREP 13 was dissolved into a generic, state-wide Local Environment Plan (2010), which provides un-enforceable ‘guidelines’ for prospective developers. Ever since, urban sprawl and ‘bold infrastructure’ have devoured the landscapes of the magnificent Cumberland Plain. Local planning regulations offer some protection but only if applied effectively. The draft Penrith Scenic and Cultural Landscapes Study (2019) noted: “…Penrith Development Control Plan contains substantial controls to manage many of the current visual detractors seen across the valley. Better implementation and compliance with these controls is required”. Such controls are urgently needed where industrial developments masquerade as ‘farm sheds’ and suburban ‘trophy houses’ ignore planning guidelines in their siting, materials and landscaping.

Locals – and friends – keep fighting The Mulgoa community will keep fighting to protect its precious valley, despite the ongoing challenges. An application to Heritage NSW to list the Mulgoa Valley as a ‘cultural landscape’ was submitted by Friends of Fernhill and Mulgoa Valley in 2020. But to succeed, there needs to be a change in the political appetite for landscape conservation, especially in a region targeted to absorb one million people over the next 30 years.

The good news is that it’s not only Mulgoa residents who want to protect the Mulgoa Valley. The Australian Garden History Society has recently added Fernhill Estate and Mulgoa Valley to its Landscapes at Risk: Watch and Action List. The Historic Houses Association wrote in its September e-newsletter: “Mulgoa Valley’s exceptionally rich landscape… is unique in the Sydney region. It is under threat from the relentless expansion of Greater Sydney”.

Sadly, exceptional landscapes are becoming increasingly inaccessible for those of us who reside in built-up areas and apartments. And when these places disappear, the sense of space, the natural horizon, and the wellbeing they provide disappear as well. If you care about Mulgoa Valley, then write to your elected representatives and tell them why it should be protected. In a rapidly changing and growing city, we need more than ever to hold on to our few remaining special landscapes.