3 minute read

Protect

Saving Heritage at the Heart of Newcastle

BY DAVID BURDON, CONSERVATION DIRECTOR

The original inspired and intimate town plan for Newcastle is coming under increasing threat from development in the name of ‘renewal’, however the adaptive re-use of several important historic buildings offers its heritage a glimmer of hope.

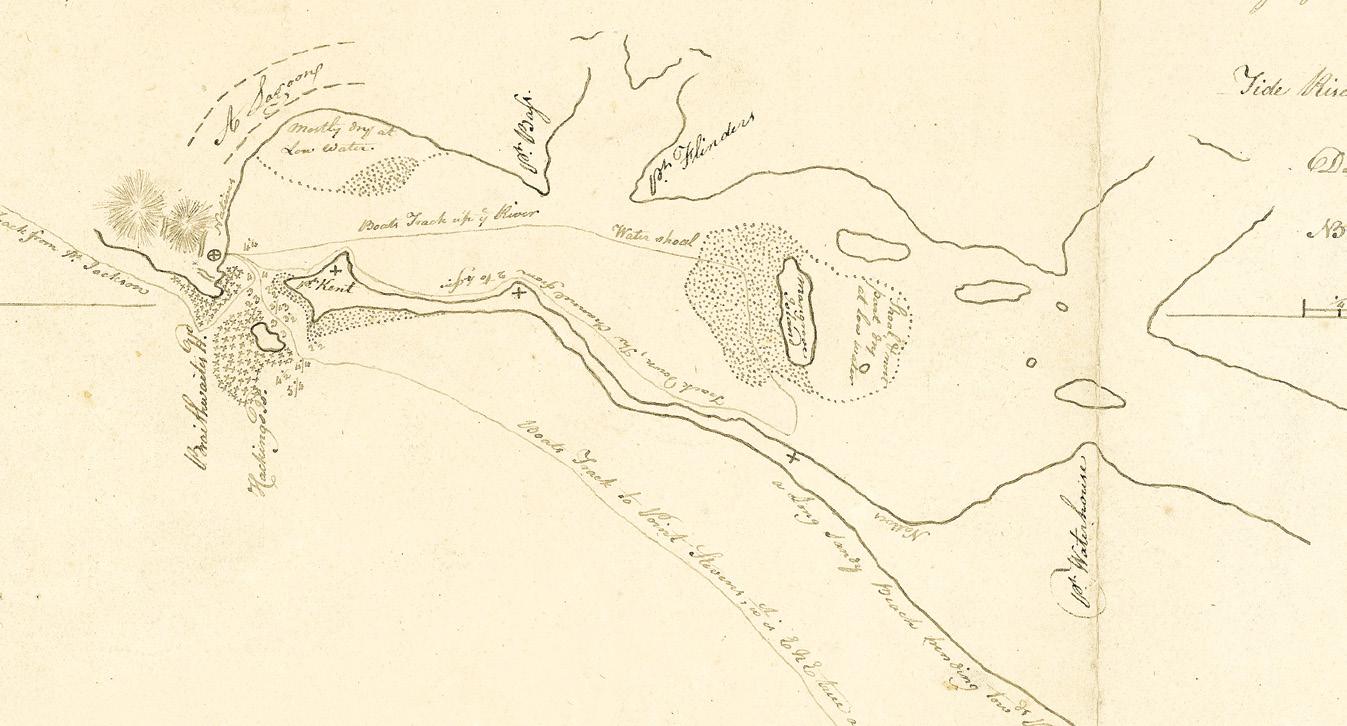

On 10 September 1797, Lieutenant John Shortland was on his way to Port Stephens in the Governor’s whaleboat. He was in pursuit of runaway convicts who had seized the Cumberland, “the largest and best boat, belonging to Government”.

Although it was raining, Shortland decided to pull into the mouth of a river where he made a short stay and prepared a sketch. The simple drawing noted a “very fine coal river”, long beach, steep topography to the south, and occupation of the country by the Awabakal and the Worimi people, who knew the river as Coquon.

Shortland named the river after Governor Hunter, but for a long while it was referred to in despatches by Governor King as the Coal River. In 1799, Australia’s first commodity export left its banks — a shipment of coal bound for Bengal.

In 1804, Governor King ordered Lieutenant Charles Menzies to establish the town of Newcastle, not only to exploit the area’s natural resources, but also as a home for recalcitrant convicts. Menzies took with him a prefabricated timber-framed building that had been assembled earlier in Parramatta, and other modest buildings soon followed.

The city grew, and as Barry Maitland and David Stafford note in their excellent Guide to Newcastle Architecture, there was one development in the 1820s which was to have “a profound effect upon the future character of the city”. Governor Macquarie decided to commission Government Surveyor Henry Dangar to do what had proved impossible in Sydney — stamp an orderly plan on the disorganised street pattern of the free town that had grown inland from the wharf.

Dangar produced a modest grid of three streets running east-west and seven running north-south, with a large central public axis stretching from Christ Church Cathedral down to the water. To the east was the Pacific Ocean, while to the west expansion was limited due to Macquarie’s granting of more than 2,000 acres to the newly-formed Australian Agricultural Company.

It was an inspired plan, on a smaller and more intimate scale than the street grids that followed for Melbourne and Adelaide. With John Horbury Hunt’s later cathedral as the crowning apex, Newcastle offered a mix of unique natural features, considered planning and good architecture. A chance for historic ‘renewal’ The steelworks and indeed even the railways have now come and gone from Newcastle, and yet still the clarity and scale of this unique city remains largely intact. For now.

The human dimension of Newcastle is at great risk as the rallying cry for ‘renewal’ sweeps across the city. The railway was removed in 2016 under the guise of reconnecting city and waterfront. Now the never-to-be-built-upon rail corridor is increasingly disappearing under apartments and office buildings, creating a far greater visual barrier than the railway ever offered physically.

Heritage Conservation Areas within Newcastle will continue to come under increasing pressure from larger developments that will drastically alter the grain of these places. However, recent projects featuring adaptive re-use of historic buildings offer glimmers of hope.

The Signal Box restaurant, Ireland Bond Store apartments, and the conversion of the City Administration Centre into a hotel, show what can be achieved when heritage is meaningfully retained. The planned restoration of the Victoria Theatre, the oldest theatre still standing in New South Wales, is another wonderful opportunity that must be grasped.

Newcastle is one of Australia’s oldest cities, arguably with the best location, and it needs to be treated with care. Newcastle can and must benefit from some well-designed new projects, so that it can indeed become a thriving place to both live and visit.

Nearly two hundred years ago, Henry Dangar came up with a plan for a unique city on a unique scale. A sudden rash of inappropriately scaled and poorly sited developments risk undoing all his good work.

From left The state-heritage listed Newcastle Signal Box, built in 1936, is now a restaurant (image by Alamy); An Eye Sketch of Hunter’s River, by John Shortland, 1797 (image courtesy of Hydrographic Department, Ministry of Defence, U.K).