27 minute read

Around the Coasts & Markets Reports

Atlantic

Maine lobstermen seek survival under whale plan

NMFS biological opinion could require ‘complete reinvention’ of the shery

ith NMFS moving toward W new northern right whale protections to meet a May 31 court deadline, Maine’s lobster shing community and state o cials contended the measure will fall hardest on a region that poses less danger to the endangered species.

In a Feb. 19 letter to NMFS’ Northeast regional administrator Michael Pentony, Maine Gov. Janet Mills said

Maine lobstermen haul traps in Stonington, the state’s lobster capital.

the agency’s recent biological opinion and its call for a 98 percent risk reduction over the coming decade will “require the complete reinvention of the Maine lobster shery as we know it.”

“After two decades and numerous regulations, the Conservation Framework now tells them that for all of their e ort, they will face additional hardship and additional regulatory actions, because we can’t adequately account

MARKET REPORT: Squid Recovery slow, but Rhode Island harvesters welcome restaurants

ore than half of all squid landings

Min the Northeast come from Rhode Island. But last year, as a result of the pandemic, some Rhode Island eets saw earnings dip by 30 percent.

Coming off a troubling year has taken great effort. Kat Smith, director of marketing and communications at Town Dock, a large processor distributor based in Narragansett, R.I., says “at this point, things are still not back to normal — although we’re glad that the light at the end of the tunnel gets closer every day. There continues to be a global shipping container shortage, covid-related disruptions, and now, the Suez Canal issue, all of which have supply chain impacts for seafood and many other industries.”

Two Town Dock products, says Smith, Rhode Island calamari (long n inshore squid) and premium domestic calamari (northern short n squid), which are both caught in Rhode Island and are Marine Stewardship Council certi ed sustainable, are always popular.

“When we look at our foodservice offerings, we are certainly better than this time last year — restaurants are ramping up with states’ reopening plans, and more people are vaccinated and excited to go out to eat. Calamari — and seafood, in general — has also enjoyed year-over-year growth in retail and grocery stores. The demand is very good; once the supply chain has sorted itself out, we are excited for the opportunities ahead.”

Much of the squid catch is exported, says Diane Lynch, chairwoman of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council. But “consumer demand for local food has risen steadily," she adds, "driven by many different factors but most notably by the consumer preferences of millennials. As part of this, consumer demand for locally caught, locally processed, locally consumed sh has been steadily growing in Rhode Island and around the U.S.” — Caroline Losneck

for, or frankly in uence, the measures being taken by the Canadian government,” wrote Mills. “Maine, and other U.S. sheries, should not have to pay an ever-increasing price for the risk facing right whales as they travel into Canadian waters.”

Ship strikes and crab gear entanglement have killed right whales there, and the Canadian government is trying to get better control. The Maine Lobstermen’s Association, while building a war chest for legal defense of the industry, gave NMFS a list of responses on behalf of a dozen New England shing groups pointing to legal and scienti c aws they see in the agency plan.

“How can our government hold Maine lobstermen accountable for right whale deaths that we know are happening somewhere else? It’s just not right, and it will not save the whales,” MLA president Kristan Porter said in a March 22 statement. The group says the last con rmed whale death entangled in U.S. lobster gear was in 2002, while 12 right whales died in Canada in 2017 and another 10 in 2019.

One dead right whale recovered o South Carolina in February had been dragging a rope “far larger than that shed in the Maine lobster shery,” as

— Kristan Porter,

MAINE LOBSTERMEN’S ASSOCIATION

was another live right whale sighted in Cape Cod Bay in January, the MLA says.

Vessel strikes o the U.S. Southeast states are another danger to right whales on their calving grounds. The species had a very good 2020-21 season with 17 young reported, according to NOAA — but that’s only in a population last estimated at 366 animals along the East Coast.

“For MLA, step one is to make sure both rules are implemented on time so that we have a shery, but with enough exibility so that lobstermen can sh safely and stay in business,” said Patrice McCarron, the group’s executive director. “Step two is to x the sub-standard science and modeling that misdirect regulatory e orts away from activities that are actually killing right whales.”

“We are looking down the barrel of a loaded gun aimed at our lobster shery. The MLA has expanded its whale team to make sure that we leave no stone unturned,” said McCarron. “We urge anyone who cares about the Maine lobster shery to support the Legal Defense Fund. Quite literally, the future of the lobster industry is at stake.” — Kirk Moore

Looking for more news?

National Fisherman is the only publication that covers the entire U.S. commercial shing industry. For daily updates, visit nationalfi sherman.com/news

Boat of the Month

Lilly Rose

Point Pleasant Beach, N.J. / Northeast multispecies trawl

Justin Hallam

ack in 2006, it was among

Ba trickle of Gulf of Mexico shrimp boats that headed up the East Coast. Today the Lilly Rose is on its second generation operating in the Mid-Atlantic trawl sheries.

“My father basically built this boat in 2006,” said Gus Lovgren, whose father, Dennis, brought what was then a decade-old Texas shrimper north to the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative at Manasquan Inlet. “At the time, everyone was switching their vessels over.”

The gulf shrimp eet was on hard times, beset by imported shrimp ooding the markets, low prices and rising fuel costs. But New Jersey shermen had gotten into the day boat scallop shery, and good prices nanced replacing aged wooden draggers.

“It made the wooden vessel eet obsolete,” said Lovgren. The northward migration of steel shrimpers has continued (see “Former La. shrimper reimagined as NJ’s Swaggy B,” NF September 2017).

The Lilly Rose shes primarily in the Northeast multispecies trawl shery, where summer ounder, black sea bass, scup and whiting are landed in their seasons. Along with New Jersey’s seasons, Lovgren holds state permits for landing in North Carolina and Virginia.

With its Caterpillar 3412 engine, the Lilly Rose is fairly matched in horsepower with the rest of the co-op eet, “but put me up against any other boat and I can get way ahead of the eet,” he said. With continuing price instability from the covid pandemic, landing that sh rst can bring an extra $1 or $2 per pound: “You’ve got ve or 10 boats that can come in on the same day and ood the market.” — Kirk Moore

Boat Specifi cations

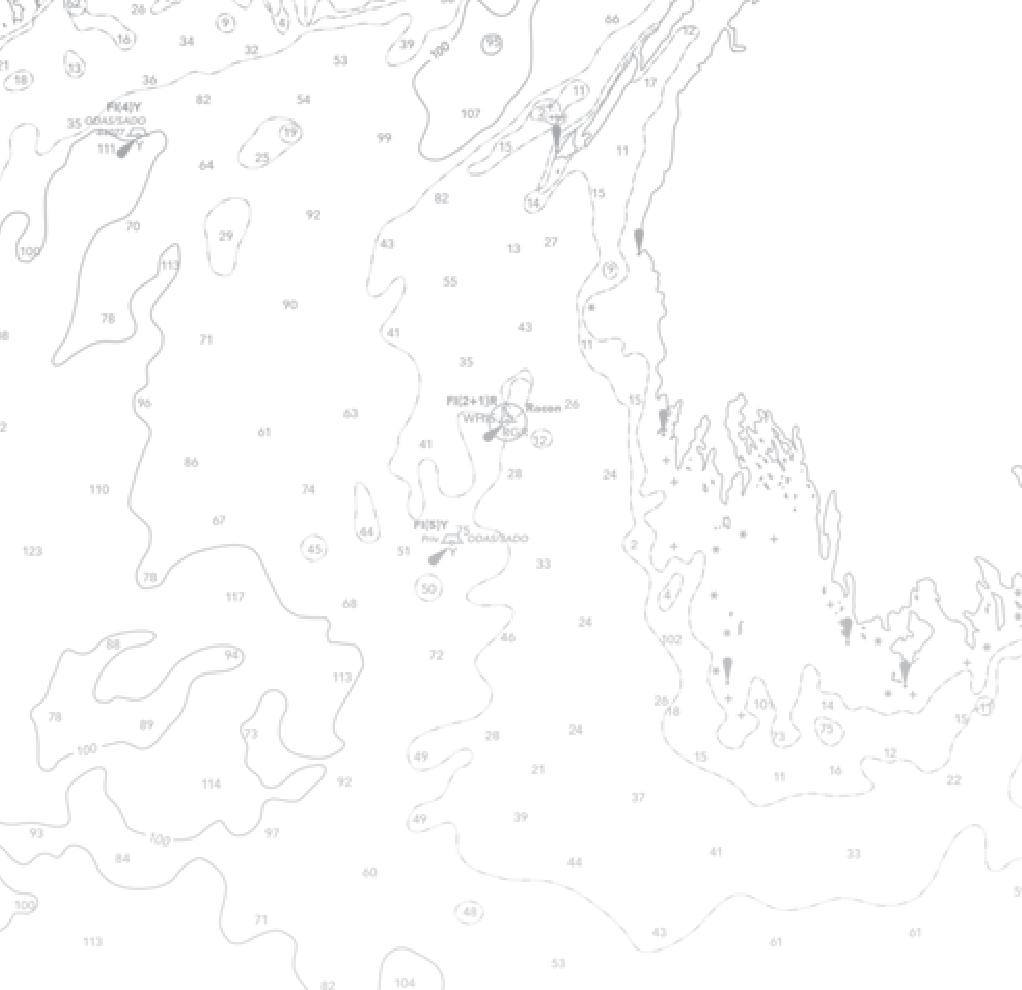

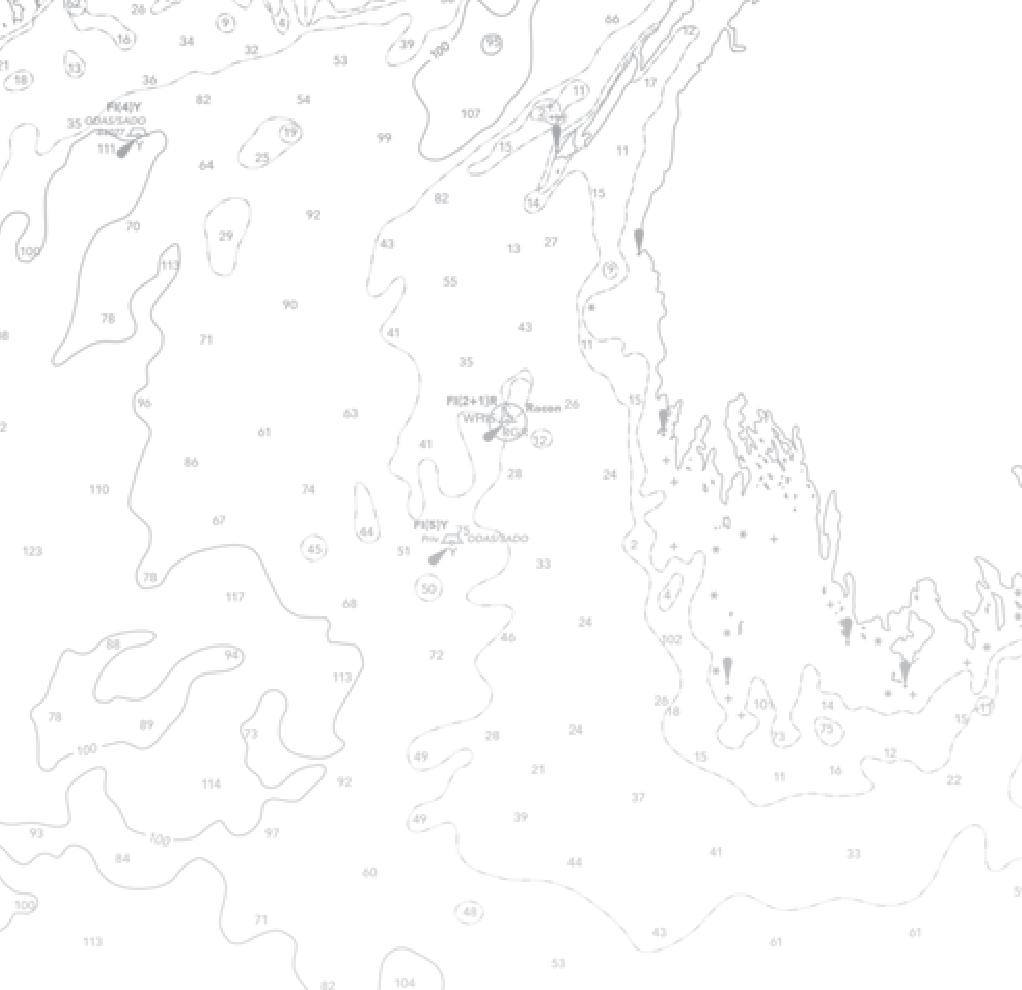

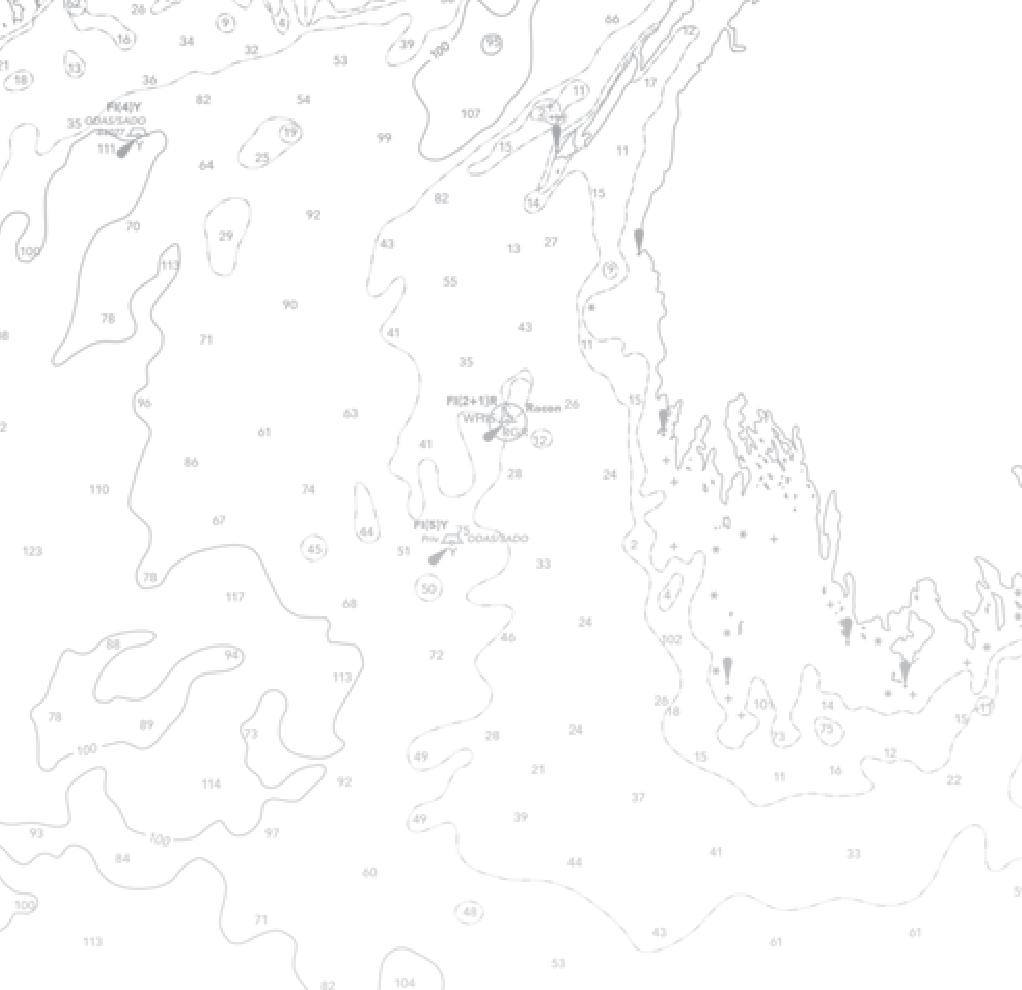

HOME PORT: Point Pleasant Beach, N.J. OWNER: Gus Lovgren BUILDER: Williams Boat Works, Coden, Ala. YEAR BUILT: 1996 FISHERIES: Summer ounder, black sea bass, scup, whiting HULL MATERIAL: Steel LENGTH: 76 feet BEAM: 22 feet DRAFT: 11 feet TONNAGE: 96 gross/58 net PROPULSION: Caterpillar 3412, 530 hp GEARING: Twin Disc 518 6:1 PROPELLER: 59-inch bronze in 60-inch Kort nozzle SHAFT: 4-inch stainless steel GENERATOR: Kubota 4 kW SPEED: 9 knots FUEL CAPACITY: 10,000 gallons FRESHWATER CAPACITY: 3,500 gallons FISH HOLD CAPACITY: 50,000 pounds CREW: 3 ELECTRONICS: Furuno suite with radar, color sounder, GPS, plotter; Icom VHF radios; two Dell PC computers; Shipmate chart plotter.

West Coast/Pacifi c

California crabbers, activists tangle on ropeless gear

Fishing advocates say technology is unreliable, would lead to more lost gear

Handling ropeless gear adds time to a day’s work. If a fi sherman spends 5 or 10 minutes more per trawl, that can add up to hours in the course of a day.

coalition of California shing A and seafood groups is grappling with environmental and animal welfare activists over state legislation to mandate ropeless gear in commercial and recreational sheries to protect whales.

The struggle is closely watched on the East Coast, where Massachusetts state sheries o cials are embarking on a one-year experiment with ropeless or “pop-up” gear aiming to reduce risks of interactions with right whales.

One tack taken by California Dungeness crabbers is to portray ropeless gear as unreliable — and potentially increasing the danger that lost gear poses to marine mammals.

“We have a pretty strong argument on our side,” said Ben Platt, president of the California Coast Crab Association. “I think the thing that resonates most is that anyone on the shing industry side who has worked with pop-up gear thinks it is unworkable.”

“There’s at least a 20 percent failure rate,” said Platt. If used widely that could lead to “tangles of lost gear… not only a huge marine pollution issue,” he said.

The bill, AB 534, was delayed in legislative committee hearings after original sponsor Assembly Member Rob Bonta (D-Oakland) was nominated by Gov. Gavin Newsom for state attorney general. Supporters and opponents of the legislation are waging campaigns by telephone and social media.

“Whales and other marine life have long been exploited by humans, nearing the point of extinction,” said Judie Mancuso, CEO and founder of Social Compassion in Legislation, a political animal advocacy group, in a statement with Bonta when the legislation was introduced in February. “It’s time we prioritize and protect our most magni cent ocean creatures and put whale entanglements in the past.”

The bill’s backers asserted ropeless gear “is the only way to eliminate entanglement risk while permitting crabbing to continue.”

“That’s why I’ve authored this vital bill, which rea rms California’s commitment to ocean conservation and sustainable crabbing operations, while also making the state a leader in crabbing technology

MARKET REPORT: Swordfi sh After big 2020 drop, fl eet looks to restaurants and Asian markets

estaurant openings and Asian mar-

Rket conditions will determine the health of the West Coast sword sh industry in 2021. Last year, supply chains in the early season were disrupted with the onset of covid-19, but as the calendar turned toward July, some markets reopened.

Though the drift gillnet shery off California operates in the nearshore waters with time and area closures, the commercial shing season for deep-set buoy gear doesn’t have hard start and stop dates.

“As for the new deep-set shery, there are currently no seasonal restrictions,” says Chugey Sepulveda, a sherman and research scientists at the P eger Institute of Environmental Research, in Oceanside, Calif. “Because sword sh are highly migratory, and the bulk of sh reside off the West Coast from about July-January, this is when we see most of the shing activity.”

According to data from PacFIN, the sword sh eet wound up at 320 metric tons for the year, down substantially from the 432 metric tons landed in 2019. As of April 2021, landings stood at 72 metric tons, and ex-vessel offerings averaged $3.06 per pound.

Meanwhile, ex-vessel prices averaged $3.89 for 2020. As a generality ex-vessel prices start out higher, in the $8 per pound range when fresh sword sh start hitting markets in July; then prices decline as volume increases throughout the remainder of the year.

The quality of sh caught with deep-set buoy gear have been fetching premium prices, but some distributors wanting to move larger volumes at lower prices on the retail end turn to gillnet-caught sh or imports, which means cheaper prices on the ex-vessel end.

“It’s shown to be highly selective for sword sh,” says Chris Fanning, a NMFS analyst in Long Beach. Catches from the deep water sets have been running up to 96 percent sword sh. — Charlie Ess

— Ben Platt, CALIFORNIA COASTAL

CRABBERS ASSOCIATION

that can be exported and used around the world,” said Bonta.

From the crabbers’ perspective, California should be exporting its success in managing whales and shing.

“This should be a model of how a robust commercial shery coexists with a recovering endangered species,” said Platt.

When the Center for Biological Diversity led a lawsuit against the state Department of Fish and Wildlife over whale interactions, the humpback whale population was estimated at 2,200 animals, said Platt. Now it’s revised to more than 7,200 with a population growth rate of 8 to 10 percent, he said.

The last con rmed interaction was in the 2020 season when a whale was released unharmed, said Platt.

In an April 1 statement, his association broke down the nancial impact of ropeless gear at “between $720 and $2,500 per device. This means that a permit owner with a 500-trap tier allotment must spend between $360,000 and $1.25 million to switch from the existing gear to ‘pop-up’ gear. By comparison, a 500-trap allotment today, including all traps, lines, buoys, and bait jars, will cost between $80,000 and $125,000.”

The association has brought seafood dealers, retailers and even recreational and charter shing operators into its e ort.

With requirements that already surpass federal protections, California’s state policy is zero interactions.

“We are onboard with the idea of trying to get there,” with the crabbers’ ideas like longlining pots and recovery by grapple, said Platt. “But they have to let us do it. — Kirk Moore

Snapshot Who we are

David Toriumi / Santa Cruz & Moss Landing, Calif.

he commercial shing

Tindustry can be hard to break into, especially if you’re not from a shing family. Doing so requires a high tolerance for risk, a willingness to endure razor thin margins for a few years, and a whole lot of hustle. But for David Toriumi, 38, getting to be his own boss and sh for a living make the dif culties worthwhile.

“It’s been a struggle even to this day,” he says. “It used to be the harder I worked the more I got paid. Now I can’t get enough time on the water to put in the work needed to make money.”

Not to be deterred, Toriumi has slowly built his shing business from the ground up.

Toriumi owns the 33-foot F/V Grinder on which he shes king salmon and Dungeness crab. He also has a 25foot Boston Whaler, F/V Salt N Season, which he uses to target California halibut, sea bass, lingcod and rock sh. The Grinder was an upgrade from a 22-foot Aqua Sport he rst bought in 2014. But to cut costs for day trips for nearshore ground sh, Toriumi added the Salt N Season last year.

He has also been a member of the California Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group working to share best practices on how to mitigate whale entanglement.

In recent years, he has also brought his catch straight to the public to increase his margins with regular dock sales in Moss Landing on weekends. He also sells for Real Good Fish, a community supported shery based in Moss Landing.

“I want to know my sh goes directly to the community. I don’t want it sitting on a shelf in a grocery store,” he says. But he also notes he doesn’t always catch the volume needed to make it worthwhile at the price many wholesale buyers offer.

Toriumi grew up working in his family’s car shop, Toriumi Auto Repair, in Watsonville, and followed in his father’s trade, becoming an auto mechanic. He’d been an enthusiastic sport sherman his whole life, spending lots of time on the nearby Monterey Bay with a rod and reel. In 2007, he was given an opportunity that would change the course of his life, a deck job picking sockeye salmon on Alaska’s Bristol Bay. Toriumi would gillnet for salmon in Bristol Bay for seven years, while still working as a mechanic. But he had the bug. He wanted to be on the water instead of in a garage, sacri cing security for the variability of the sea.

“I saw a lot of opportunity in doing something I love,” he says. “I often question that decision, but I’m hoping I can hang on.”

Toriumi lives in Prunedale, Calif., with his wife and two young sons; River, 7, and Ronan, 3. He takes them down to the boat and shows them his craft when he’s tied up. Sometimes River will join him for day trips, and in a few years Ronan will join, too.

“I love looking back at land and hearing the traf c and sirens fade away. You can’t even buy that,” he says. “The freedom and the hard work are what I love, watching the weather and following water conditions, guring out where the sh will be.” — Nick Rahaim

Gulf/South Atlantic

NMFS delays excluder rule for skimmer trawls

Agency could again consider excluders for vessels under 40 feet working in shallows

A sea turtle escapes through an excluder.

Anal rule requiring the use of turtle excluder devices in the Southeast shrimp skimmer trawl sheries that was to take e ect April is pushed back to Aug. 1 — a delay forced by pandemic restrictions, according to NMFS.

The rule will require TEDs designed to exclude small sea turtles on skimmer trawl vessels 40 feet and longer and amend the de nition of trawl time.

However, safety and travel restrictions “have limited our Gear Monitoring Team’s ability to complete the in-person workshops and training sessions on the nal rule that we had anticipated and communicated to the public,” according to a statement from the agency.

“The delay in the e ective date is to allow NOAA Fisheries additional time for training shermen, ensuring TEDs are built and installed properly,

— Ryan Bradley,

MISSISSIPPI COMMERCIAL

FISHERIES UNITED

and for responding to installation and maintenance problems when the regulations go in e ect.”

That additional time is key to the roll-out, say stakeholders.

“The rule is quite cumbersome and costly for businesses to implement, thus the extension was warranted,” said Ryan Bradley, executive director of the Mississippi Commercial Fisheries United industry group. “There is some

MARKET REPORT: Yellowfi n Producers foresee a good season ahead as sushi buyers return

series of strong storms roiling the

AGulf of Mexico this winter and early spring coupled with a slow reopening from covid-19-related restrictions has dampened yellow n tuna production in the Southeast, with boat prices hovering at about the same levels as this time last year.

David Maginnis, who runs Jensen Tuna in Houma, La. — the gulf’s largest yellow n producer — says boat prices for the premium quality No. 1 tuna average $6.50 per pound while the No. 2 sh are about $3.50. According to the latest landings data provided by NMFS, shermen have harvested 30.7 metric tons (67,584 pounds) between Jan. 1 and Feb. 28 — way down from the same period in 2020 when 76.7 metric tons (169,137 pounds) were harvested.

“Lately, in the Gulf of Mexico, it’s been rough, rough, rough,” Maginnis said. “We’ve been ghting a lot of bad weather. Does that equate to higher boat prices? No.”

Maginnis, whose sh house runs 18 tuna boats and supplies customers all over the United States, said the restaurant industry is the main driver of his higher-grade product — especially the white-tablecloth and sushi establishments.

“The No. 1 (grade tuna) is very affected because you don’t have the sushi bars opening up,” he said.

Another covid-related wrinkle is the increased cost of shipping and handling — air freight, trucking, fuel, packaging — that contribute to lower boat prices,” Maginnis said.

“This sh is worth only what the market says,” he added.

But Maginnis believes production will pick up this spring when, hopefully, the weather calms down and more restaurants reopen to full capacity.

“When the weather is good, it’s good. We’re going to have a good production year. It might be one of our better years coming up.” — Sue Cocking

very speci c criteria that these turtle excluder devices must meet and they have to be installed a certain way to be deemed legal.”

TEDs cost on average $1,000 or more for a pair — not including installation, net modi cations and backup gear, said Bradley. His group estimates per-vessel costs at $5,000, plus less money coming in when catch e ciency declines an estimated 2 to 10 percent.

“In Mississippi and Louisiana, gear reimbursement programs utilizing BP restoration funds have been established to help vessels cover some of the costs of compliance,” Bradley added. However, shermen contend it is not enough. A $700 maximum in Mississippi and will cover only some of the installation costs.

“It is not that easy to just throw this TED gear in these types of skimmer trawls,” he said. “You’re talking about having to cut two $10,000 nets in half, add an additional section of webbing, and sew in the new TEDs to NOAA’s exact speci cations.”

Other measures to protect sea turtles in skimmer trawl sheries may lie ahead. NMFS is again considering expanding the TED requirements to skimmer trawl vessels less than 40 feet in length, and whether additional rulemaking is warranted.

The rule dates back to a 2015 lawsuit by the environmental group Oceana that alleged NOAA and its sheries agency were violating the Endangered Species Act by not doing more to protect turtles from accidental capture in shrimp nets.

The nal rule excluded skimmer boats under 40 feet, pusher-head trawls and wing net or butter y trawls from the new requirements — which at the time NMFS said would reduce economic impact of the new rule by 73 percent. But in announcing the e ective date delay, NMFS also indicated that decision could be revisited.

Bradley thinks that’s likely, with ongoing pressure from environmental groups dissatis ed with the under-40-foot vessel exemption.

“Regardless of how the industry feels about the rule, shermen will have no choice but to comply,” he said. “MSCFU has and will continue to o er guidance and consultation to help Mississippi’s shermen comply with the rule should and when it reaches nal implementation if it survives potential legal challenges.” — Kirk Moore

— NMFS

Alaska / National

Senators seek changes to Coast Guard mask mandate

State’s push re ects national industry sentiment that CDC rule is unreasonable

P.O. 1st Class Nicolas Santos operates the cutter John McCormick’s small boat alongside the F/V Tenisha Rose in Alaska’s Sitka Sound during a fi shing vessel safety inspection.

Alaska’s U.S. senators are working to revise the masking requirement for all persons aboard commercial shing vessels.

A Coast Guard Marine Safety Information Bulletin issued on March 22 stated its o cers can restrict vessel access to ports and operations if they fail to follow the rules as de ned by the Centers for Disease Control.

“Vessels that have not implemented the mask requirement may be issued a Captain of the Port order directing the vessel’s movement and operations; repeated failure to impose the mask mandate could result in civil and/or criminal enforcement action,” the bulletin says.

The CDC mask requirement has been interpreted by the Coast Guard to apply to “all forms of commercial maritime vessels” including cargo ships, shing vessels, research vessels and self-propelled barges.” It requires “all travelers” to wear a mask, including those who have been vaccinated.

“Senator [Lisa] Murkowski and I have been pressing this relentlessly on a call with the Coast Guard commandant, a call with the White House guy who’s supposedly in charge of all the CDC issues. We had a meeting with the head of the CDC. We are trying to explain to them how, no o ense, but just how stupid this is and how uninformed it is,” Sen. Dan Sullivan said at a ComFish virtual forum.

“And it could be a safety issue, not with regard to covid, but with having to wear masks when you’re out on the deck of a ship in 30-foot waves trying to bring in gear or pots. So, we’re going to continue to work on that one.”

“The CDC has planted their heels on this one as I understand it,” echoed Doug Vincent-Lang, commissioner of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “Certainly, from a realistic standpoint, it makes no sense. So we’re on the front side of that conversation.”

Vincent-Lang added that he is

MARKET REPORT: Salmon With pandemic experience, fl eet gears up for 2021 harvest

laska’s salmon industry stood A poised to ll hungry markets as the season began. On tap for Bristol Bay, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game has projected a harvest of 37.4 million sockeyes. If that pans out, the bay harvest will account for 80 percent of the statewide projection of 46.6 million sockeyes.

At a potential harvest of 124.2 million sh, the pink salmon season should be no slouch either. That’s double last year’s 60.7 million pinks and could push this year’s harvest of all species to more than 190 million sh.

Last year’s canned salmon markets were already starving for product in the preamble of the pandemic, and demand for canned salmon surged even higher as the world went into shutdown and stock-up mode. With limited canning capacity among processors and skeleton crews prepping salmon for llets to be distributed fresh or frozen, the bulk of the harvest went into freezers in its H&G form. Some shermen were forced to stop shing until their respective processors caught up with huge volumes that had been delivered.

“There were shutdowns with some processors,” says Harry Moore, longtime commercial gillnetter in Bristol Bay. “Some folks missed several tides.”

Though shermen worried that the higher volume of H&G product and the lower volume of value-added sockeyes would hurt end pricing and ripple its way back to ex-vessel pricing, many processors paid retroactive settlements far beyond the base price of 70 cents per pound.

Many shermen received icing, refrigeration or delivery incentives that put them up to around 90 cents per pound. Loyalty in delivering to particular companies yielded settlements of around 20 cents per pound for shermen delivering 100,000 pounds and up to 40 cents for shermen giving processors 300,000 pounds or more. — Charlie Ess

— Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska

speaking with members of other coastal states and hopes to garner support to overturn the mask requirement.

“I think to the extent that we can form some kind of a uni ed position on this issue across more states, we stand a better chance of changing it. Because this is a CDC guidance which can be changed depending upon how they get policy direction from the White House. And if they hear from other coastal states in addition to Alaska, they’ll probably be more inclined to do it,” he said.

Feedback on the masking rule can be given at wearamask@uscg.mil.

The CDC masking requirement, issued to protect operators and passengers on public and commercial modes of transportation, has been interpreted broadly by the Coast Guard to apply to “all forms of commercial maritime vessels,” even those that do not legally fall under the category of transportation — “including but not limited to cargo ships, shing vessels, research vessels, self-propelled barges.”

The original CDC order requires “all travelers” to wear a mask, including those who have been vaccinated. With the Coast Guard interpreting commercial shing crew to be included in this mandate, it would follow that vaccinated crew members would still be required to mask up. The only broad exemptions are: • When “eating, drinking or taking medication for brief periods” (but not for use of tobacco). • When the crew member is a solitary worker in the work area (for example, when standing watch). • While communicating with a person who is hearing impaired when

Oregon Sea Grant

Critics of the Coast Guard’s mask mandate say it can be a dangerous impediment to fi shermen’s ability to communicate while at work.

the ability to see the mouth is essential for communication. • When necessary to temporarily remove the mask to verify one’s identity. • If unconscious (for reasons other than sleeping), incapacitated, unable to be awakened, or otherwise unable to remove the mask without assistance, experiencing di culty breathing or shortness of breath or feeling winded may temporarily remove the mask. — Laine Welch and Jessica Hathaway

Kodiak, Alaska

Tony Pirak is neck deep in Paci c gray cod on the F/V Anthem out of Kodiak, Alaska.

This is your life. Submit your Crew Shot www.national sherman.com/submit-your-crew-shots