5 minute read

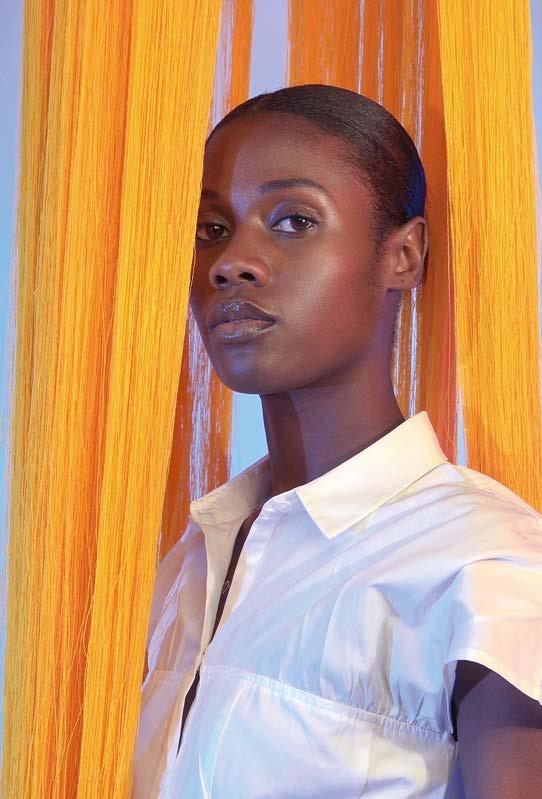

NA CHAINKUA REINDORF Nubuke Foundation curator Bianca Ama Manu in conversation with this emerging artist

Words BIANCA AMA MANU Photography TEKNARI

Nubuke Foundation curator Bianca Ama Manu meets with the emerging Ghanaian artist

Advertisement

NA CHAINKUA REINDORF

Striking and sensual, there’s no denying the allure of Na Chainkua Reindorf’s undulating and multi-dimensional handwoven tapestries, often with freeformed edges, containing thousands of meticulously sewn-in patterns of iridescent beads. Her mixed media works incorporate folds, moulds, weaves and wefts to paint colour fields that enchant you in their process. I can confess so from my own experience: I was introduced to Reindorf through Accra’s Nubuke Foundation and have been an avid supporter ever since, showing her work during ART X Lagos 2018 to great success. Living between Accra and New York State, where she recently completed the MFA programme at Cornell University, I caught up with Reindorf as she was preparing for her solo show this summer at Anthony Brunelli Fine Arts in Binghamton, New York State — the result of three years of conversation between Reindorf and John Brunelli, co-director of the gallery.

BIANCA AMA MANU Your practice often involves an element of constructing and building immersive tapestries or sculptural installations; tell me about your process and how you invite people to engage with your work? NA CHAINKUA REINDORF I focus on creating an experience rather than just making artwork. I often craft work that appears to me in a flash of inspiration — usually in a dream — I wake up excited about making it happen. I’m always thinking about my work and the spaces it will occupy; I like it to play off of architecture and interior spaces to achieve an encompassing experience.

From the very beginning of my practice, I have been obsessed with this idea of making work from scratch. There is something special about weaving the textile yourself, making it to your specifications and then subsequently transforming it. My sweat, blood and tears are literally imbued within the very fibre of the work. Sometimes a piece can take months to complete.

I often return to the same materials, fibres, yarns, threads and more recently, beads, all of which have loaded histories, especially within the context of African culture. I am interested in finding ways through which we can encounter these assembled materials in the form of my artwork, which allows us to focus on their beauty, complexity and intricacies, rather than just their potential for utility. It is an idea of working with materials that have long been relegated to craft, and transforming them into sculptural pieces that are arresting and take up space so that they are noticed, encountered and confronted. It is as much about the work as it is about my hand. BAM How did you form a relationship with the Nubuke Foundation? NCR I was first introduced to Nubuke Foundation back in 2009. I participated in a textile dyeing workshop spearheaded by Kofi Setordji, a renowned Ghanaian artist. I was also the first artist chosen to show in the Nubuke Foundation’s prestigious Young Ghanaian Artist (YGA) programme, which provides a platform for promising artists whose works display a depth of knowledge in their chosen craft. BAM You seem to love texture: from beading, braiding, baskets and weaving, all of which are strong emblems of West African culture. How do you marry references to traditional West African textiles with contemporary art? NCR I am fascinated by the craft, art and design divide, and freely admit that my work plays with all of these elements. I like that my work is difficult to categorise. I fi nd inspiration in traditions that have stood the test of time, but have also evolved with the times in ways that are visually evident. A great example is masquerade costumes in West Africa. If you look closely at some of these costumes, you can see that the materials used to construct them are a hybrid of traditional mixed with more contemporary sources. In one costume, you can find traditional woven cloth, Dutch wax prints, and more contemporary imported textiles such as sequinned fabrics, combined with synthetic yarn, cowrie shells, western dolls, Christmas tinsel, plastic and glass beads. And these outfits are fantastic. They are the epitome of exaggeration, bordering on outrageous and bizarre. BAM You’re a self-professed ‘colourphile’ — as your multiple Instagram moodboards attest. I’d like to hear more about how you relate to colour? Who are some of your influences? NCR Yes! I am obsessed with colour. My heart literally starts beating faster when I see something that plays masterfully with colour. I find a lot of inspiration in geometric forms and colour play in unexpected combinations. A great example is sculptor El Anatsui. His work flirts with simplicity and complexity by assembling countless bottle caps into larger-than-life, tapestry-like pieces.

I also have a wide range of influences outside of art, like the architect Luis Barragán, whose buildings are masterful iterations in terms of geometric form, colour and space, and fashion designer Iris van Herpen, whose clothing designs are more artistic sculpture than they are clothing. BAM Tell me about your new body of work and exhibition with Anthony Brunelli Fine Arts. NCR I’m focusing on the theatrical nature of the masquerade costume; the artifice, the spectacular, the haunting, the memorable. I’m thinking about the sheer mastery of the construction of the costumes, and have reduced them to their most basic elements of colour, texture, space and scale. I read about how the members of the clans that compete in the fancy- dress festival in Winneba, Ghana, can take up to a year to complete their costumes. Considering that my practice does require a lot of work, I was taken with this idea of a labour of love, with emphasis on the word labour. I’m pushing myself creatively by making intricate, time-consuming work, but also paring back to allow the materials to speak for themselves. Also, the majority of the masquerade traditions exclude women, so this show is a tongue-in-cheek way of responding to that, a way of inserting myself, a woman, into the history.