12 minute read

King Magnus VI’s Law of the Land in the Codex Hardenbergianus

Mid 14th century

The landslov, or Law of the Land, promulgated in 1274 by King Magnus VI, is a milestone in European legal history. As only the third nationwide legal code to be introduced in Europe, it remained effective until superseded in 1687 by Christian V’s Laws of Norway. The landslov transformed Norwegian society, established legislation as an instrument of government, granted rights to the weakest in society, and laid the foundations of the Norwegian state.

Of the 39 intact manuscripts and over 50 manuscript fragments that have survived, the Codex Hardenbergianus is the most beautiful. The manuscript, written in Old West Norse in Bergen in the mid 14th century, contains 10 decorated and illustrated letters of the alphabet (known as illuminations) that convey the essence of the text.

The Codex Hardenbergianus is a bound volume containing several legal texts, the biggest and most important of which is the landslov. The volume also contains legal amendments and new laws that were later introduced to supplement or supersede parts of the landslov, and Archbishop Jon Raude’s ecclesiastical laws.

The most significant legacy of the landslov from 1274 is the idea that we should follow a set of accepted laws, rather than allowing power to be the determining factor. Thanks to our legal tradition stretching back to the landslov, Norwegians today associate the word ‘law’ not with repression and abuse of power, but with rights and freedom.

Owner: The Royal Library, Denmark.

The complete Holy Scriptures, translated into Danish 1550

The religious upheavals started by Martin Luther in 1517 had significant knock-on effects for culture. The Reformation brought a strengthening of individual faith and a weakening of the church’s role as a mediator and interpreter. Instead, the word of God – the Bible – became the focus of religious life. This meant that the Bible had to be translated from Latin to the vernacular, the language spoken by the people. Following the invention of the printing press in Europe in the mid 15th century, it was now possible to produce books faster, at lower cost and in larger numbers.

The Bible on display here, known as the ‘Reformation Bible’, is the first complete Bible in Danish. It is printed in 1550 and largely based on Luther’s German translation of the Bible from 1545. The typefaces and illustrations, however, were the very same that were used for printing a Low German Bible edition in 1534. The ‘Reformation Bible’ contains 85 woodcut illustrations in total.

The Reformation spelt the end of Norway’s political independence. The country was placed under the Danish crown, and the king was made head of the church. A portrait of Christian III is one of the first things encountered by readers of this Danish bible. The king’s gaze is directed heavenwards, and in his ungloved hand he is holding a scroll containing the word of God. The coat of arms on the second page symbolises his earthly power.

Printer: Ludowich Dietz, Copenhagen.

A ‘letter from heaven’ was a chain letter, asking the recipient to copy it out and send it on. The letter displayed here is a handwritten copy. According to the letter, the original was written by “the Lord God Himself” and sent via an angel to Constantinople (presentday Istanbul), where it was said to have hung in the air in golden letters. Anyone who copied out the letter and sent it to others would be forgiven all their sins. Those who didn’t believe it and didn’t copy it would die, and their children would “suffer a wicked death”. When Judgement Day came, anyone who had the letter in their home would be spared all torments. The letter earnestly implores the reader to live according to God’s commandments and the words of Jesus, and to attend church on Sundays. It is signed “I, the true Jesus Christ”.

Although few letters of this kind have survived, we know that the ‘letter from heaven’ was a popular genre in post-Reformation Europe, where the church no longer offered confession and forgiveness.

The text of such letters remained remarkably constant throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The letters were copied by hand, but printed versions were also in circulation, often beautifully decorated and coloured. These one-page letters were easily carried around and sold. Printers made good money printing them in large runs, as many people were willing to buy salvation and happiness for a shilling or two.

‘Letter from heaven’, back

Dated 1604

This ‘letter from heaven’ is dated 1604. But the paper it is written on bears a watermark showing the coat of arms of the city of Amsterdam, which proves it could not have been written before 1675. We do not know why the letter was backdated.

The fold lines show that the letter was folded in five, probably so the owner could carry it around as a lucky charm. This may have been a frequent occurrence, as the folds are worn, and holes have formed where they intersect. The parts that faced outwards when the letter was folded up are darker. This suggests that the letter was in use, carried in a pocket or next to the skin, and was read or shown off repeatedly.

Norske IntelligenzSeddeler was Norway’s earliest newspaper. This first issue was published in Christiania in May 1763. The publisher and editor was Samuel Conrad Schwach, a Prussian-born printer educated in Copenhagen.

In Christiania, Schwach had published periodicals of various kinds before launching the newspaper. It was not an easy process. There was heavy censorship, and the authorities only issued licences to publish newspapers in Copenhagen, where they could keep a close eye on them. Schwach got round this in part by limiting the content to advertisements, business news and religious reflections. As was typical in those days, he also benefited from knowing the right people: in this case Nicolai Feddersen, a state councillor and former chief magistrate of Christiania. It was in Feddersen’s interest to have a hold over Schwach, since he owned shares in the paper mill that made good money from supplying the newspaper.

Over time, Norske IntelligenzSeddeler was able to broaden its content, but it was not able to include real political stories until 1814, when press freedom was enshrined in the new Norwegian constitution. The newspaper remained in circulation until 1920, when it was incorporated into Verdens Gang.

This first issue of Norske IntelligenzSeddeler contains little in the way of what we would now call journalism. An introductory verse greets the reader, emphasising that this is a Norwegian publication: “This paper carries Norwegian reporting of one thing and another that might be of value.” In this way, it hints at a distinctly Norwegian perspective, while remaining ultracautious in expressing its patriotism. The rest of the content consists of simple announcements of ship arrivals and departures, items for sale, births, marriages and deaths, and seizures of stolen goods – plus an article on how to store lemons to keep them fresh over the winter in Norway.

Perhaps of most interest to the modern reader is a short, moralistic reflection on how intelligent people may be more inclined to criticise the mistakes and shortcomings of others than to correct their own. We no longer know who this barb was aimed at in 1763, but the sentiments are no less relevant today.

The original newspaper was printed in Fraktur, or Gothic type, which to modern eyes can be hard to decipher. The pocket to the left of the display contains a transcription.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter: Siælens Sang-Offer, hymn book 1685

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, who wrote the words to hymns, was the first professional author in Norway under Danish rule. Her first book, Siælens SangOffer (‘Song Offerings of the Soul’), was published in Christiania in 1678. No first editions have survived, but no fewer than seven editions were published during Engelbretsdatter’s lifetime alone. Thanks to her direct, easily sung language, she became one of the 17th century’s most popular authors.

Several of Engelbretsdatter’s books featured a detailed illustration of the author as a frontispiece on the page facing the title page. The portrait in this edition of Siælens Sang Offer , dating from 1685, shows a middle-aged woman writing. On the desk in front of her are a skull and an hourglass: common baroqueera motifs symbolising the transient nature of life. In this portrait, the motifs also allude to the profound personal experiences of Engelbretsdatter. Seven of her nine children had died in infancy. If life had taught her anything, it was that death awaits us all. This is a recurring theme in several of the book’s hymns.

‘Evening Hymn’, which is still included in the current (2013) hymnal used by the Church of Norway, refers to the hourglass running out.

Published by Christian Geersøn, Copenhagen.

6

The Norwegian constitution of 1814 placed legislative power in the hands of parliament, the Storting, and limited the powers of the monarchy. Representatives were to be chosen by an electorate consisting of male citizens over the age of 25 who owned a certain amount of property. Although this covered only 40–45% of Norwegian men – women’s suffrage was not yet on the agenda – this was a radical measure by the European standards of the time. The constitution was not only liberal in nature, but also guaranteed Norway a high degree of independence in its union with Sweden. It therefore became an important symbol of Norwegian national solidarity.

In the 1820s, printers began producing the constitution in poster form, and these political icons became popular wall art, usually mounted and framed. This 1836 version is especially lavishly decorated. The illustrations depict Eidsvoll manor, where the constitution was drawn up over six weeks in the spring of 1814, and some of the representatives who attended that assembly or the first extraordinary session of the Storting in the autumn of that year, when the union with Sweden was agreed. Although dated 4 November, the constitution contains only minor changes from the version adopted on 17 May. At the bottom are the signatures of the 79 members of the Storting.

Lithograph: J.C. Walter. Publisher: Prahl.

Not everyone felt included in the Norwegian political community. Established by labour activist Marcus Thrane in 1849, ArbeiderForeningernes Blad was the first newspaper in Norway to campaign for workers’ rights. Thrane, a bold and tenacious advocate of social reforms and extending the franchise, led what became known as the ‘Thrane Movement’ – Norway’s first mass political movement. In 1850 he petitioned the king with a series of demands, including universal suffrage. Although the Norwegian constitution was liberal by the standards of the time, there were limits on the freedom of expression, especially when it was used to mobilise the working class – and so Thrane was sentenced to seven years in prison.

On 4 June 1853, Arbeider-Foreningernes Blad devoted its front page to proposed constitutional amendments that had been drawn up by Ludvig Kristensen Daa, a historian and politician. The proposed changes all related to extending the franchise.

8 Draumkvedet as sung by Maren Ramskeid, manuscript c. 1840–1850

The 19th-century collectors of folk tales, songs, tunes, dialects and artefacts were driven by the idea that these were all expressions of a deep-rooted popular culture – the ancient, fundamentally stable culture of a nation. The collectors’ work was therefore also a search for a shared national myth.

In Norway, this attitude to culture was widely embraced. Famous collectors included Asbjørnsen and Moe, Ivar Aasen, Ludvig Mathias Lindeman – and Magnus Brostrup Landstad, a priest and hymn writer. At some point in the 1840s, he wrote down the words of Draumkvedet (‘The Dream Ballad’) while Maren Ramskeid, a servant girl from Telemark, sang the ballad to him. The version by Ramskeid and Landstad is the most complete one known to us, and at the time it was used as a basis for attempts to reconstruct the original.

Draumkvedet describes a vision so comprehensive that it invites comparisons with Dante’s Divine Comedy. Contemporary experts are unsure as to the ballad’s age and whether the many different transcriptions can all be considered parts of the same ballad.

Landstad’s hastily written manuscript is full of corrections and additions – a striking contrast to the illustrated book edition by Gerhard Munthe in the drawer below.

1 Agnes Buen Garnås: Draumkvedet, 1984

Recording published by Kirkelig Kulturverksted | 2:24 (excerpt)

2 Arne Nordheim: Draumkvedet, with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Ingar Bergby (conductor), Grex Vocalis, 2006

Recording published by Simax Classics | 4:27 (excerpt)

8 Moltke Moe (ed.) and Gerhard Munthe (ill.): Draumkvæde. A Medieval Poem

1904

This beautifully produced edition of Draumkvæde (‘Dream Ballad’) features illustrations and artwork by Gerhard Munthe. Even the lettering is hand-drawn. As well as the ballad, this edition includes a few additional details. It mentions briefly that the text was edited by Moltke Moe, “a professor of the Norwegian vernacular committed to promoting the Norwegian folk tradition” – or what we would nowadays call a folklorist. He held Scandinavia’s first professorship in folklore studies, which was indicative of a transition from a romantic to an academic approach to the subject.

Moe was commissioned not only to edit the text, but also to produce a scholarly commentary. This was a complex task, and one that Moe never completed – much to the frustration of Munthe and the publishers, whose first release this was. For a long time they hoped to publish a supplement containing Moe’s commentary, but this never happened. Munthe’s book thus became a one-of-a-kind literary treasure, modern in style but lacking the intended academic dimension.

Published by Forening for Norsk Bogkunst (Norwegian Book Art Association), Kristiania.

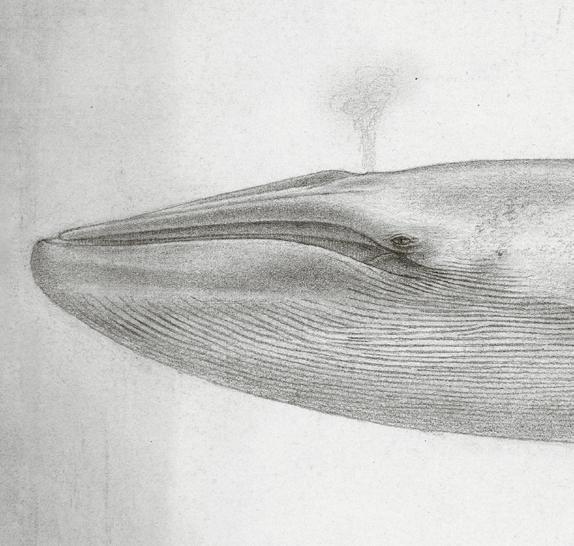

Georg Ossian Sars: Scientific drawings of starfish, cod, crustaceans and blue whale

c. 1860–1890

Georg Ossian Sars was Norway’s leading zoologist in the latter half of the 19th century and is still one of the most frequently cited Norwegian scholars of natural history. As a young man, he spent much of his time at sea, being paid by the government to help develop a scientific basis for Norwegian fisheries and later the whaling industry. Among his discoveries was the fact that cod roe floats on the surface rather than sinking, and in 1865 he succeeded in artificially fertilising the roe. After becoming a professor of zoology in 1874, Sars published many scientific papers, especially on crustaceans. The material on display here shows his exceptional talent as a scientific illustrator.

Sars was one of a small group of people who dominated Norwegian public life on both the scientific and the artistic front. His brother Ernst was the great Norwegian historian of the day. One of his sisters, Mally, was married to the composer and conductor Thorvald Lammers. Another sister, Eva, studied with Lammers and was a celebrated romance singer when she met and married Fridtjof Nansen, who had also started out as a zoologist – and illustrator. Georg Ossian Sars himself, besides being a prominent scientist and illustrator, was also a decent violinist. His works exemplify the cross-pollination that occurred between art and science.

9

Although he could not rival the scientific achievements of Georg Ossian Sars, the folklore collector Peter Christen Asbjørnsen was also a zoologist and was among the first to present Darwin’s theory of evolution to Norwegian audiences. In 1853 he discovered a hitherto unknown species of starfish in the Hardangerfjord at the remarkably great depth of 380 metres. It was not previously known that life existed at such depths. He named it Brisinga endecacnemos, after Brisingamen, the necklace of the Norse goddess Freya.

Sixteen years after Asbjørnsen, Sars discovered another starfish species, Brisinga coronata, at depths of up to 600 metres off the Lofoten islands. Sars described his discovery in an article written in English and published in 1875. He sent a copy to Charles Darwin, who replied with a friendly and appreciative letter in April 1877:

Dear Sir,

Allow me to thank you much for your kindness in having sent me your beautiful memoir on Brisinga. It contains discussions on several subjects about which I feel much interest. I congratulate you on your discovery of the new proofs of Autography which promises to be of much service to those who like yourself are good draughtsmen.

With the most sincere admiration for your varied works in Science, I remain, dear Sir

Yours very faithfully

Charles Darwin

Henrik Ibsen: Peer Gynt. A dramatic poem, first edition, and second edition with handwritten amendments

1867

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt is considered one of the great works of Norwegian literature, on account of both the quality of its language and the complex character study of Peer Gynt – which many people have also described as a study of the quintessential Norwegian character. Ibsen started work on the play in Rome in 1867 and wrote most of it on the island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples. The first performance took place almost a decade later, in 1876, at the Christiania Theater, with a musical score by Edvard Grieg.

Ibsen drew inspiration for the character of Peer Gynt from P.C. Asbjørnsen’s Norske HuldreEventyr og Folkesagn, a collection of legends and folk tales published in 1845, in which Per Gynt is described as “a huntsman in Kvam in the olden days”. He is said to have outwitted mountain trolls and “the Great Boyg of Etnedal” – and he had a reputation for telling tall tales.

Ibsen’s Peer Gynt is likewise someone adept at inventing stories and escaping reality. In the play’s opening line Aase, Peer’s mother, exclaims: “You’re telling lies, Peer!” He is “himself enough”, but like an onion has no innermost core. Wherever he travels, the Boyg is lurking, enticing him to “go round about”.

First edition published by Den Gyldendalske Boghandel (F. Hegel), Copenhagen.

Second edition (1867) with amendments, mainly linguistic modernisation, by Henrik Ibsen and others for the third edition (1874).

10