5 minute read

Mental health and marginalised communities

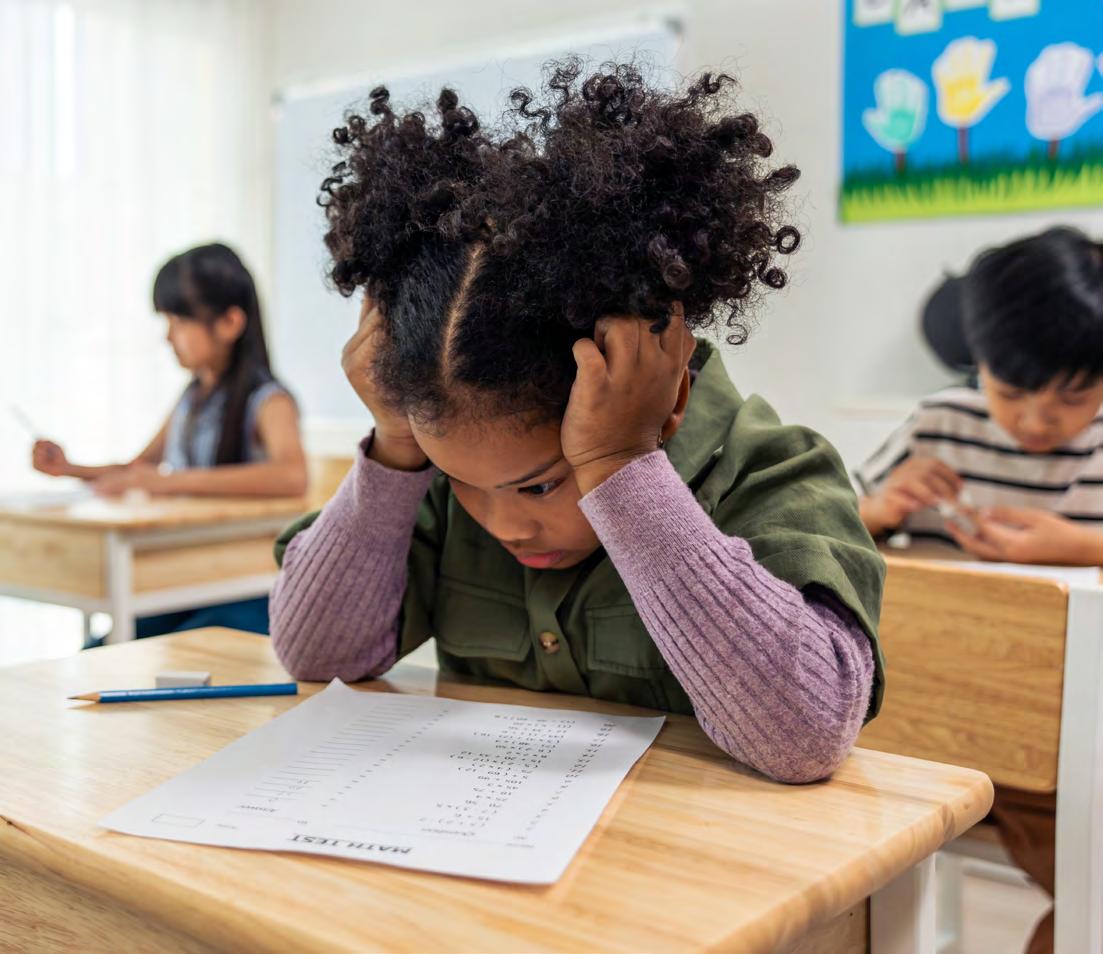

Nathan Rutter outlines some of the challenges facing children of colour with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs in mainstream education.

The identification and support for children with SEMH needs has been a subject I’ve wanted to highlight for a long period of time. As a SENCO of British and Goan heritage in Bristol, I want to help others build an understanding of the challenges facing students of colour with SEMH needs in mainstream settings. To do this, I explored the societal context of mental health within communities of colour; the current state of these communities receiving SEMH provision, and the impact of disadvantage on their mental health.

Policy And Practice

The UK Race Relations Act of 1976 was the first policy that stated the rights of people of colour (POC) to be given access to facilities or services within education if they had a special need. However, subsequent acts have failed to include specific mention of protections to POC. They have also failed to refer to how a lack of understanding of intersectionality can cause professionals to lose sight of all the barriers facing these children. The Equality and Human Rights commission in 2014 provided further guidance to schools on how they should implement the act into their own policies, making sure they remove any policies or practices that were discriminatory to those of different ethnicities. It is important to note that whilst the Department for Education’s (DfE) Code of Practice suggests organisations should consider training staff to better identify additional mental health needs, there is no mention or guidance on students or groups from different communities. The Royal College of Psychiatrists noted this same weakness in their own policies and highlighted the need for policy reform to improve the practices of their staff to eradicate discrimination in the workplace.

The Role Of Camhs

Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) referrals can come from parents through GPs, schools or social care pathways. Data shows that children of colour are ten times more likely to be referred to CAMHS through compulsory channels compared with white British children, with referrals often coming from education or social care pathways. It also identified that referrals from GPs for students of colour were three times more likely to be rejected by CAMHs. When analysing the data, disparities were found within different communities; GPs were referring more white children to CAMHs than would be expected, whereas black and South Asian children were more likely to receive referrals by specialist doctors, and black and mixed heritage children were most likely to be referred by social services. Our academy data reflects the same trend, with more children of colour being referred through social care and educational pathways. When speaking to POC governors, parents and staff members and reviewing research, there is an acute awareness that a lack of cultural understanding plays a role in discriminatory behaviour, which has a trickle-down impact on children’s reflections of race and discrimination in school settings and the barriers to them receiving support.

Academics have pointed to several factors for this: a lack of diversity in the workforce; language and cultural barriers; as well as the evidence of historical discrimination within the sector. In 2018, the Royal College of Psychiatrists stated that a lack of cultural understanding could be impacting the level of care POC receive. Work has been done to improve policy and implementation within the NHS, however, a 2020 report stated that although there was an over-representation of people of colour in the NHS, there was under-representation in senior positions. This filters through to a lack of expertise around different cultures; at the Royal College of Psychiatrists it found that only seven per cent of NHS Trust board members are from an ethnic minority background.

The Impact Of Disadvantage

The Government’s statistics before the pandemic found that one in four children from Asian households and one in five children from black households were growing up in ‘persistent poverty’ compared with one in ten white British households. Recent research points to Socioeconomic Disadvantage (SED) having a detrimental impact on both the physical and mental health of the child, in particular their tendency to seek attention from others. Researchers found links between SED and ‘delayed reward discounting’, a form of impulsive decision making, suggesting that the child’s emotional reactivity was affected on a neurological level, disrupting their decision-making ability. I work in a diverse secondary academy that is made up of many different communities of colour, and even at their young age some of them have already experienced racism in society.

Research released in 2020 points to data around Islamophobia that has shown a weak but significant link between Muslim identity and higher levels of depressive symptoms. When running sessions with many of these students, what often comes up is that staff and people in the Bristol community don’t understand their culture and beliefs, which can lead to conflict and a feeling of alienation. Evidence backs up the statement that the cumulative impact of racism on a regular basis in someone’s life has a long-term impact on their mental health. The Equality and Human Rights Commission acknowledges that mental health issues affect people of colour more severely, leading to an increased likelihood of poverty, poorer educational outcomes, unemployment, and interaction with the criminal justice system.

Our Data

A recent survey sent out to students in our academy aimed to analyse student resilience and mental health across the school to better understand the needs of our different cohorts.

The results showed that black Caribbean and mixed white and black Caribbean students showed some of the lowest scores within our school, whereas those from Asian communities scored higher. Interestingly, students from larger communities that share cultures and religions had some of the highest scores, whereas those from smaller communities showed the lowest scores. Research on the relationship between social status and health has shown that ethnic and religious minorities reported better health when contextual diversity was higher in their communities. Ethnic minorities and Muslims even reported better health than most of their population when the societal disparities such as social status were minimal.

As a result of the findings, the mental health team started implementing a ‘positive role models’ campaign for targeted groups. The campaign advised tutors to contact at-risk students to provide extra support to families, and researched extra training around diversity and positive mental health on student attainment and wellbeing.

A study in 2019 looking at the impact of disadvantage on children of colour suggested that social and community relations play a large role in their mental health development, and that improving these relationships may play a large role in the children’s wellbeing. In the context of my academy, our catchment area falls within the bottom ten per cent of deprivation within the UK, therefore a large proportion of our students are far more likely to face many forms of socioeconomic adversity affecting their educational attainment, wellbeing and life chances. In the current era of Covid 19 these factors have been exacerbated, as the mental health and education of students in these communities has been impacted more than most. It is critical that school leaders reflect on this idea of building communities and cohesion within their environments, to engender a sense of belonging and remove the barriers children growing up in social deprivation experience. My hope is that the increasing understanding and acceptance of diversity within education and healthcare drives the issue forward, so that schools and mental health services are better able to support every child from every community in the UK.