10 minute read

George A. Grant—Whaleman—First Curator of the Whaling Museum

G e o r g e A . G r a n t — W h a le m an F i r st C u ra t o r o f t h e W h a lin g M use u m

THE MAN WHO brought William F. Macy's dream of a Nantucket Whaling Museum to a reality was a man eminently qualified for such an assignment—George A. Grant—whaleman. Here was a Nantucketer who had lived in the full tradition of the whaling industry. Born on October 28, 1857, on the Island of Upolo, in the Samoan or Navigator group in the South Seas, (where his mother had been placed ashore for the event by her husband, Captain Charles Grant), the first sounds he heard were the surgings of the sea on the coral reefs near the hut where he was born. Three weeks later, "wrapped in banana leaves", as he so often described the incident, he was taken aboard his father's ship, the Mohawk, of Nantucket, held proudly in his mother's arms.

Fiction, with all its beguiling, would not be quite equal to the recounting of the story of his parents, Captain Charles Grant and his wife, Nancy. Captain Grant was one of the greatest whaling masters out of Nantucket or any port in the 19th century. Mrs. Grant spent thirty-two years at sea aboard whaleships with her husband. The couple's three children were born in the far Pacific Ocean. Charles, the eldest of the three, was born in 1850 on the famous Pitcairn Island; her daughter, Ella, was bom at the Bay of Islands in 1855; and, as recounted, George A. was born in 1857 at Upolo Island.

Following Captain Grant's arrival in the Samoan group to recover his wife and baby son, the Mohawk continued her regular cruisings for whales before finally re-crossing the Pacific to round Cape Horn, homeward bound. Fitting out at Nantucket for another voyage never materialized, as the owners sold the ship to New York. But Captain Grant's reputation was well known and he was offered the command of the New Bedford whaleship Japan, and sailed on May 31, 1859, for the Pacific Ocean.

But Mrs. Grant found her life ashore on Nantucket, with her children, so completely unlike her years at sea with her husband, that she determined to join the Japan. Taking the youngest child, George, she s ai l e d f r om N e w Y o rk t o M e l b o u r n e, A u s t ra l ia, o n t he s hi p B e l l e o f T h e West. She had received a letter from Captain Grant telling her he intended to be at the Bay of Islands in a certain month in 1860, and here the family was reunited. News that the Civil War had broken out was learned several months after the Fort Sumter incident, when the Japan was cruising in the South Pacific.

GEORGE A. GRANT 17

Returning to New Bedford in 1863, the Japan was promptly sold to Boston, and Captain Grant was again without a ship. But not for long, as he was given command of the whaler Milton, which sailed from New Bedford in November, 1865, and returned in 1869, after a voyage which yielded 2,800 bbls. of sperm oil — a highly successful voyage, and a "highwater" mark in Captain Grant's career. In 1870, Captain Grant took out the whaleship Niger from New Bedford, and again his wife and son, George, accompanied him on the voyage, which lasted until August 10, 1874.

Upon the return of the Niger, George Grant decided to strike out on his own and shipped in New York on board the merchantman Governor Morton, bound for California. Upon arrival at San Francisco he left the ship to get a better berth on board the schooner Seminole, sailing adross the North Pacific Ocean to Yokahama, with a cargo of American wheat below hatches. Loading tea, the Seminole's voyage took her through the China Sea, the Straits of Malacca, the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape-of Good Hope to Liverpool. After a voyage to Dublin, the schooner returned to New York.

It was summer, 1877, when young Grant left New York for his island home. His two years in the merchant service had been exciting, vigorous and pleasant. But the spell of the great sperm whale was in his blood. Only a few weeks did he remain home, then going to Edgartown, signing on the whaler Mary Fraser as boatsteerer or harpooner. The voyage lasted three years. In August, 1880, he again rounded Brant Point.

Promotion was next in order. When the bark Alaska sailed out of New Bedford in 1880, George Grant was her third mate. He had stayed home a little longer this time — six weeks.

But he had managed to find time to get married. The wedding took place on the 13th of September, 1880, and on the very next day he embarked on the whaleship, bound for the Pacific— a bridegroom for a day!

The voyage of the Alaska occupied three years. During a cruise on the Chatham Islands' whaling grounds in the South Pacific there occurred an incident which the old whaleman recalled as one of his happiest.

The captain of the Alaska happened to be on deck with his spyglass one morning and sighted a ship. All the officers trained their various types of glasses on the object, but young Grant's were not strong enough to distinguish the vessel's name. The captain, with a twinkle in his eye, let his third mate borrow his spyglass. Grant took one look and cried aloud: "It's the Horatio — my father's ship!"

18 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

The Captain consented for young Grant to go aboard the Horatio in exchange for her third officer for a two-days' cruise. Going aboard, however, was the highlight of the incident.

Neither his father nor his mother had been home when he shipped on the Alaska. The Horatio had been out three years and was filling for home at this time. As the Alaska's boat approached the Horatio's rail, young Grant saw a Nantucket boyhood acquaintance — Arthur Folger — leaning over the rail. Resolving to have a little fun, he averted his face and, as he climbed aboard, kept away from Folger. Going aft quickly, he knocked at the cabin door. His father, thinking it an officer, invited him in without going to the door. As he entered the cabin, his mother, who was seated at a desk across the room, gave him a quick glance, turned away — then looked back at him swiftly: "My goodness, boy!" she cried, bounding out of her chair. "Where'd you drop from!"

The mother was soon asking questions of home. Her daughter had been married during her absence, and her first query was: "What kind of a man did Ella marry?"

"He's a New York man," replied the son, going on to tell about the wedding. "But, mother, you haven't asked me yet what kind of girl I married."

"What! Boy! — you married?"

Grant left the Alaska at New Zealand, remaining in the Bay of Islands for a year and a half, returning home in 1884.

In 1889, his active whaling career came to an end. Journeying overland to San Francisco, he signed on the ship Young Phenix, Captain Millard, for a cruise in Alaskan waters after the right whales. Returning to the old home port of Nantucket late in 1890, he settled down to a life that took him only a short cruising radius of his island home.

His long career afloat, embracing thirty-two years of practically continuous life aboard ship, so became a part of him that the many incidents occurring therein, though of more than ordinary interest, were but casual bits of sea life to him. What he considered outstanding was a happening like that of Christmas Day, 1872. It was a memorable day for the Niger, his father's ship. During the preceding two months, Grant's father had requested the master of every whaleship spoken that he try to be in a certain longitude and latitude in the South Pacific on Christmas Day — so that each with his wife might come on board and take Christmas dinner.

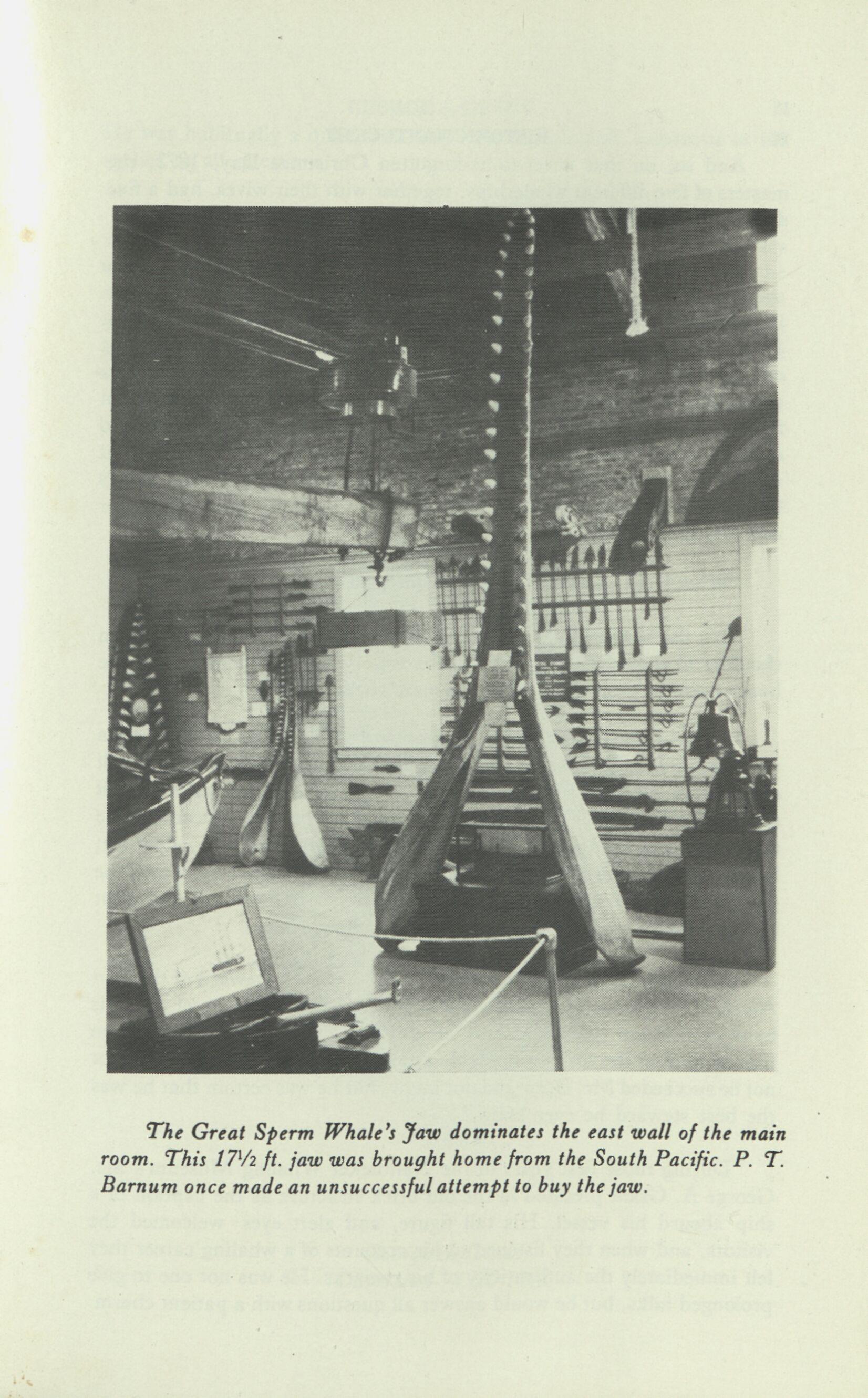

The Great Sperm Whale's Jaw dominates the east wall of the main room. This 17V2 ft. jaw was brought home from the South Pacific. P. T. Barnum once made an unsuccessful attempt to buy the jaw.

20 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

And so, on that never-to-be-forgotten Christmas Day, 1872, the masters of five different whaleships, together with their wives, had a fine dinner of stuffed pig in Niger's cabin.

Being in a whaleboat when it was "stove" by the powerful flukes of a sperm wnale was not an unusual occurrence for George Grant. And yet, he only mentioned one, and that time marked a most humorous incident. It seems that the whaleship's pet—a monkey—got into the mate's boat one day and hid under the stern deck. The mate lowered and was fast to a whale before the monkey was discovered. Of a sudden, the sperm's great flukes side-swiped the boat, turning her completely over. The second mate came up to the rescue as fast as his men cou,J pull. Young Grant was on deck with his father and was su~ rised to see the second mate's boat suddenly lose headway and the men lean over the oars. His father was watching through his glass smiling.

"What's the matter?" asked the puzzled boy.

"It's the monkey," laughed his father. "He has been running from shoulder to shoulder of the men in the water that are hanging onto the boat — now he's dancing a jig on the mate's head."

The whalemen were fond of pets aDoard ship, no matter if it were a monkey, parrot, goat, or Galapagos turtle. Goats were the most difficult of the lot. A good many ships out of Nantucket in the early days would not whale it on Sundays. Mr. Grant often recounted the yarn concerning the mate who was reading his Bible one Sunday when he was called aft, leaving the Bible on the main hatch. When he returned he interrupted the goat busily chewing on the "good book". The volume was- rescued—but the goat had chewed his way from Genesis to Revelations.

All manner of men sailed in whaleships. Take^the steward of the shi" Niger, for instance. He had been a head chef in a Boston hotel until his habit of drunken sprees lost him one position after another. It was then that he took to the sea in a laudable attempt to cure himself. Whether or not he succeeded Mr. Grant did not know, but he was certain that he was the best steward he ever knew.

During those first years of the Nantucket Whaling Museum's life, George A. Grant presided in the old brick structure as the captain of a ship aboard his vessel. His tall figure, and alert eyes welcomed the visitors, and when they listened to his accounts of a whaling career they , .felt immediately the authenticity of his remarks. He was not one to give prolonged talks, but he would answer all questions with a patient charm.

GEORGE A. GRANT 21

He was habitually a quiet man, and was inordinately courteous in his replies to all questions.

To the many visitors who entered the Whaling Museum he was remembered for his role as the last representative of the 19th century whaleman. As he began his final yeai as Curator, at the age of 85, he retained his erect bearing. On occasion, when he gazed from the winnows toward the harbor waters, there was a look in his eyes which belonged to a generation of seafarers of Nantucket that have long since vanished from the scene.

—E.A.3.

George A. Grant Custodian—1930-1942