3 minute read

Ke Ala Kūpuna

from No Nā Kānaka

Ke Ala o Nā kūpuna

Following Ancestral Pathways

In Hawaiian thought, names encode profound ancestral knowledge accumulated over countless generations about the characteristics, deeper meaning, and purpose of a place. Lele is an older name for Lahaina and this treasured place was poetically referred to as Ka Malu ‘Ulu O Lele, which celebrates the shaded breadfruit groves that adorned a lush, fertile, and abundant landscape.

Deepening our understanding of Lahaina’s history and traditional names can act as a beacon along our healing journey. Like the proverb that teaches us “i ka wā mamua, ka wā mahope,” meaning our future can be found in our past, we look to the rich and storied history of Lahaina as our zenith star on this voyage of healing and rebirth.

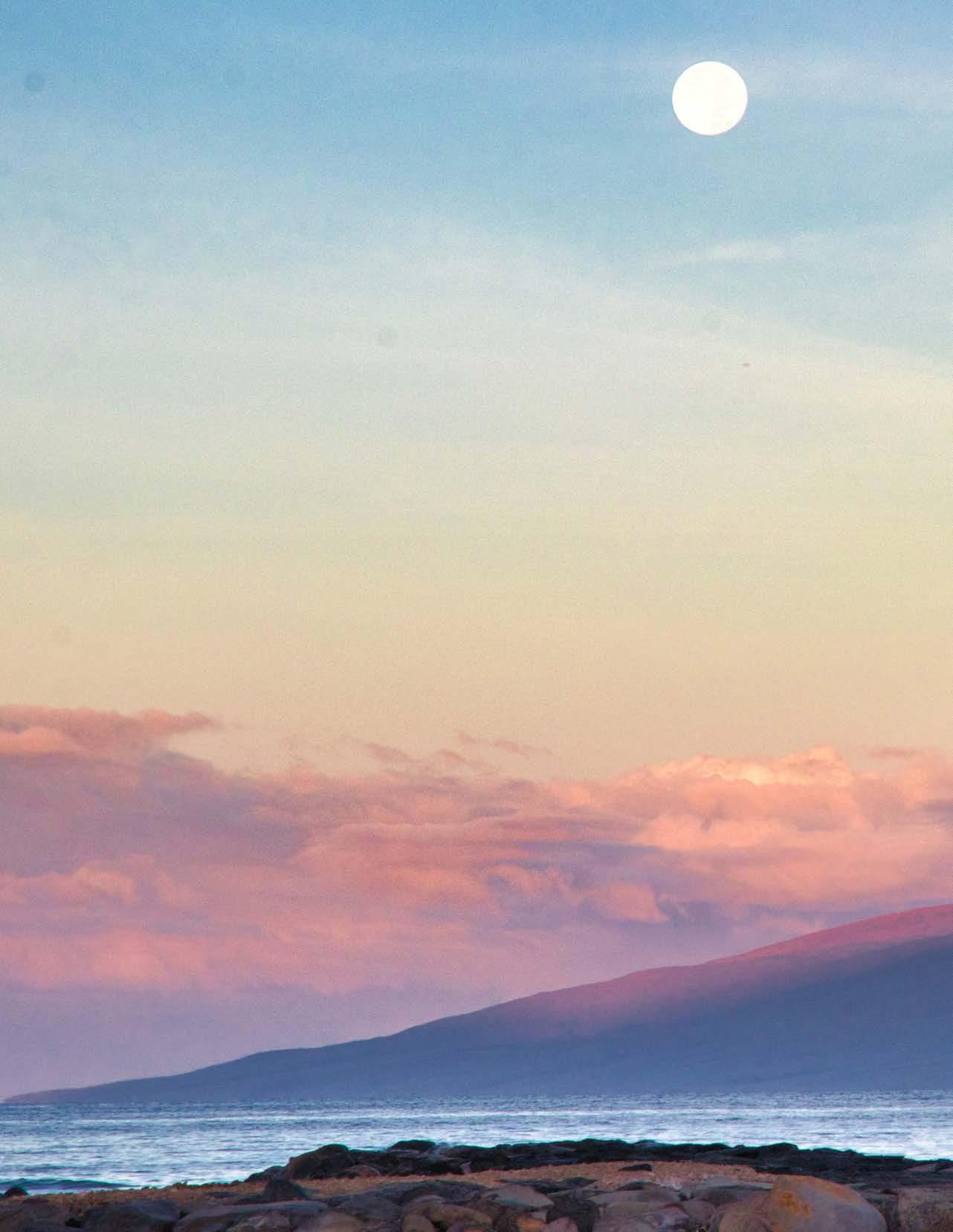

Lahaina is situated on the Leeward side of Kahālāwai, the West Maui mountains, characterized by abundant water, narrow ridges, deep valleys, and steep slopes. Kahālāwai means the meeting place of waters, or the place where heaven and earth meet. The summit at Pu’u Kukui at 5,788 feet elevation is a pristine and intact native forest which extends down to mesic forests and native shrublands.

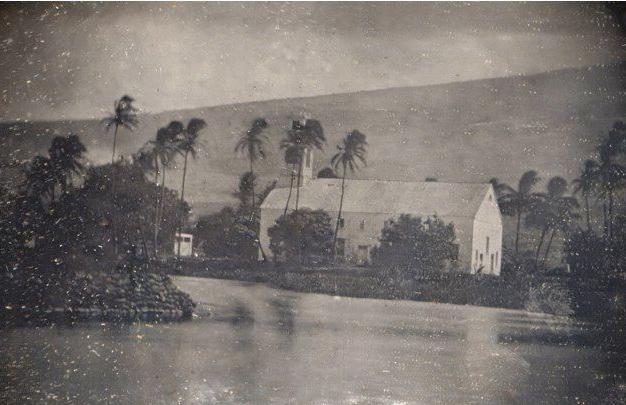

Lahaina was nourished by numerous perennial streams and springs that sustained floodplains and wetlands including a 17-acre pond at Mokuhinia surrounding the small island of Moku’ula. Kānaka Maoli worked in harmony with the natural environment to protect the wetland ecosystems of Lahaina for millennia sustaining life in an uninterrupted continuum.

Native species and traditional crops including ‘ulu, kalo, ‘uala, hala, kukui, and niu flourished. Large ‘ulu groves cooled the landscape, increased transpiration, and enhanced rain patterns to keep Lahaina lush, while providing protection from the powerful Kaua’ula winds. A complex and interconnected system of ‘auwai and fishponds were carefully maintained to support food production while decreasing flood risks. Due to its abundance, Lahaina was the royal seat of renowned ali‘i since the 1400s and recognized as the Capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the 1800s.

In the past two and a half centuries, Lahaina has undergone immense social, environmental, and cultural disruption that drastically shifted its ecosystems from the mountains to the sea. From the early 1800s, waves of extractive industries including whaling, sugar, pineapple, and mass tourism has taken a tragic toll on Lahaina.

The privatization of land in the mid-1800s and increasing political pressure displaced many native families from ancestral lands that they had stewarded for generations. In more recent times, native families have continued to be displaced by Hawai’i’s astronomical cost of living to such a point that there are now more Hawaiians living on the mainland than in Hawai’i.

What was once floodplains, taro patches, and wetlands has become arid, fire-prone landscapes vegetated by invasive grasses. No longer beckoned by shady ‘ulu groves, the rains that once drenched the pili grass falls sparingly. The fishpond at Mokuhinia is a dusty field and beloved Moku’ula resides only in the stories, chants, and songs of our people.

As we seek to heal and rebuild Lahaina from the devastating impacts of the August 8th fires, it is imperative that we understand the greater context of our work. We root ourselves in a continuum that extends thousands of years before us and extends forward for thousands of years to come.

LELE

To fly, ascend, jump, leap, burst forth; to sail through the air, as a meteor; to land, disembark, as from a canoe; to undertake; to move, as stars in the sky. A sacred altar used in traditional ceremony.