11 minute read

Circular economy

Josephine Philips, founder and CEO of SOJO, is a fashion-tech platform that seeks to make clothing alterations and repairs as easy and hassle-free as possible Their platform works by connecting its users to SOJO’s in-house team of tailors and local seamster businesses to collect their items to be altered or repaired

Advertisement

Customers can book the service via SOJO’s website or app, and their repaired/ tailored garment will be returned in 5 days All pick-ups and deliveries are done via bicycle to limit carbon emissions

In terms sustainability SOJO is a good example of a circular economy as it works to keep garments in circulation The app makes it easier to maximise the longevity of our clothes whilst increasing the number of uses per product At the same time, the app equips tech savvy Gen Zs with the tools they need to overcome the typical sizing challenges of unique, second-hand items from resale platforms such as Depop and Vinted And potential barrier to reaching seamsters

By putting your postcode on the app, it presents you with your local seamsters with photos, a description and example prices so that users can decide which one they want to use After that, you input what needs to be done (e g , 'trousers, waist in’) and then choose a date and time for order to be collected SOJO also offers their service on B2B basis for brand partners

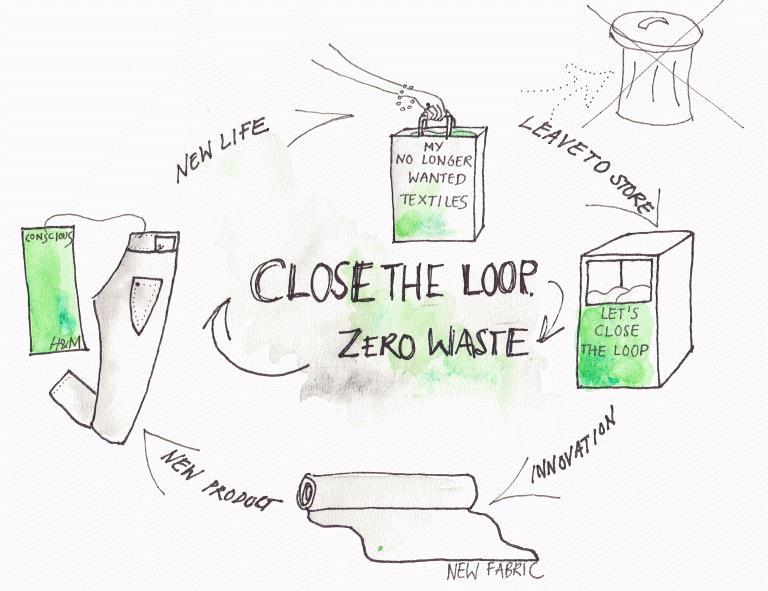

Circularity is far bigger and more ambitious than simply recycling

According to Dr Christina Raab, vicepresident of strategy and development at the Cradle-to-Cradle Products Innovation Institute, circularity involves thinking more holistically about sourcing, use and reuse “Many brands still focus solely on using or increasing recycled content”, says Dr Raab However complete circularity begins with selecting the right chemicals and materials that are not only safe for people and the environment but allow for high quality materials available for future use and cycling

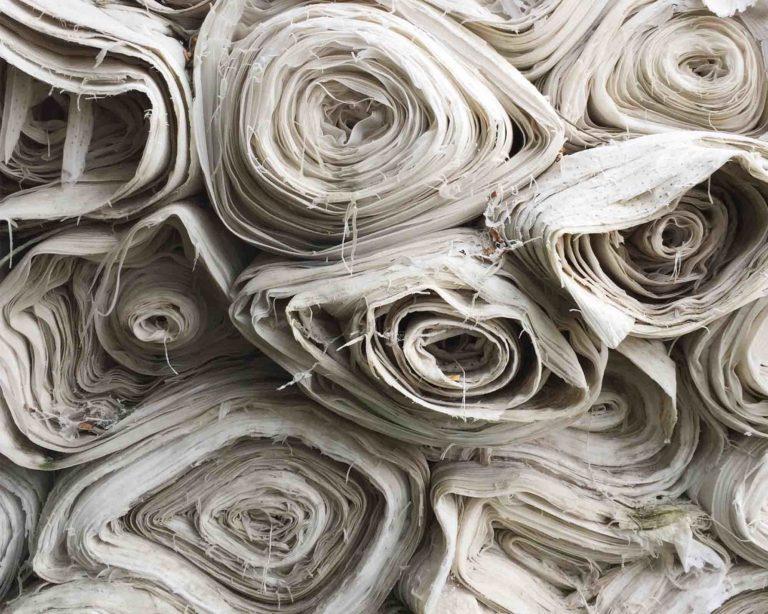

Cradle to Cradle is attempting to address this through a certification programme where it measures “material health” of denim, dyes, elastics and other components of in clothing It was first introduced in William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s 2002 book, “Cradle to Cradle: remaking the Way We Make things” It encourages using safer materials, conserving energy and water, and created closed loop systems where waste is eliminated

In 2010 the pair officially set up the certification system and methodology and revealed it to the public through the Cradle-to-Cradle Products Institute They also launched the Fashion Positive programme, working with a community of pioneering brands such as Stella McCartney to clean up fashion, reduce waste and male clothes fairly and efficiently

To be certified, companies must go through the rigorous certification programme led by the Cradle-to-Cradle Products Innovation Institute The Cradle certification has different levels of recognition: Bronze, Silver, Gold and Platinum Each level represents a different level of commitment to environmental sustainability

The Bronze level certification means that a company has assessed the environmental risks for the final manufacturing stage and the product has an environmental policy in place A plan must be developed to implement the said environmental policy at all manufacturing facilities and will be evaluated on progress at recertification The silver level certification means that the company has management systems in place support the implementation and oversight of their environmental policy at their manufacturing facilities

The gold level certification means that a company has responsible sourcing management systems in place to support the implementation and oversight of their environmental policy within the product’s supply chain Platinum, the highest level of recognition, means that a company has incorporated environmental objectives into their employee performance evaluations and provides incentives for top management and employees to actively participate in achieving in the company’s environmental goals

At any of the given stages of certification, it demonstrates the level of commitment a company has put towards sustainability (I e , the use of safer and more sustainable materials, closed loop recycling and the use of more responsible labour practices) This is part of the reason why the Cradleto-Cradle certification is such a useful too particularly for consumers to making informed choices; this is regarding researching better brands to support and try to understand their impacts

However, while the Cradle-to-Cradle certification covers many aspects of sustainability, it does not cover everything That’s why it is still important to look for other certifications and labels, such as the fairtrade certification

The reuse of materials may seem rational from a business perspective as new materials cost money, and economists have argued that waste streams can be turned into revenue streams, but there are financial considerations to address For second-hand retailers it has been rather successful business making money from a growing market for used goods On the other hand, it's harder for clothing brands to reuse old garments to turn into new ones Only a handful of brands (for example Patagonia, which are consistently create upcycled collections out of old pieces) are even attempting to do this

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a nonprofit focused on the circular economy, has been working with more than 90 fashion brands on its Jeans Redesign project Suggestions made highlighted the big difference simple changes can make For example, rivets on jean pockets are very difficult to remove to the point where it can mean the entire top of a pair of jeans has to be cut off and discarded prior to recycling Hence- so why put them on in the first place Small adjustments might seem insignificant, but they can be impactful when executed on scale As the circular economy is a broader concept, so it requires the whole system to be able to operate to support it

Circular design, however, won’t solve all fashion’s environmental mishaps warns Matt Dwyer, vice-president of product impact and innovation at Patagonia, a brand that has been pushing towards an ever-less wasteful business model

“Recycling has been touted as a way to perpetuate bad behaviours and overconsumption”, he says “The rental/recommence model, when deployed in a manner that perpetuates consumerism, doesn’t actually solve the problem that many think it does

Other obstacles to surpass, Dwyer notes, include a lack of infrastructure for collecting old clothes to resell or turn into fibre and the reality that recycling itself uses energy, which sometimes comes from fossil fuels Plus, endlessly recycling synthetics such as polyester will do nothing to solve the microplastic pollution problem

In essence: circular fashion is no swooping answer to the problem at hand But with growing momentum from all corners of the fashion industry, many believe we are on the road to a promising new era of circularity

Chief Sustainability Officer

Global fashion brands are now looking at sustainability as an opportunity as CEOs are now realising that sustainability is good for business as it enhances creativity and consumer appeal (given that consumers are more aware and sensitive of the fashion industry negative environmental impacts) From a talent perspective, there has now emerged the need to hire a highly evolved Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO)

Globally, this is one of the most soughtafter roles for most fashion and apparel companies The role of a CSO can be thought of as a translator As both the external environment and the global sustainability agenda is changing so fast, this calls for a person to translate what is going on in the external environment to inside an organisation

In the past the role has often been restricted to the technical/engineering aspects of the business, ensuring that a company meets necessary green compliances, liaising with external stakeholders like environmental activists and consumer groups, as well as implementing effective corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes The last few years have changed the scenario

Today, the CSO plays a key role in making product and process-orientated decisions Fine-tuning operations by reshaping, reorganising and reworking the green strategies of an organisation in line with stakeholders The so-called climate emergency has led to chief sustainability officers becoming increasingly influential and expanding their research into product development, manufacturing and marketing

To be clear CSO roles in the fashion industry are not new, at least not globally, LVMH (Louis Vuitton) has had a Sustainability Director since the nineties, however, now this is becoming more of a norm (for businesses of all size) than aberration

On an individual level, an ideal CSO needs to have the ability to quickly and clearly perceive global megatrends and the organisation’s position in light of this megatrend Emphasis on an organisation's position; research conducted by Deloitte UK found that over 80% of people in CSO-type roles were personally approached and were promoted from within the firm they were working in More than anything this shows how insight knowledge (of a company), and contacts are heavily valued in this role

The CSO must be an inspirational leader who can look at the bigger picture It is quite likely that going forward the CSO may well lead business strategy for companies and pave the way for more CSOs in the C suite

O think that in the same way there is a CRO- Chief Risk Officer- there'll be a CSO because there will always be a new sustainability issue, whether that’s biodiversity, palm oil or deforestation, or ocean management

Some think that the role will eventually become similar to the CEO, because if you're not sustainable then you're not in the game forever, or at least in the long run

Some think that the role will end up going to the CFO- Chief Financial Officerbecause ultimately performance will be managed on an agreed capital basis from financial to natural to social capital

And then others predict it will be integrated in everyone’s way of working, in the same way that there used to be a chief digital officer, and that’s just faded away because digital is the way of working So, it just becomes a small part of everyone’s job

As time passes it will be interesting to observe which of the four proposals the future of the CSO role takes, or perhaps one that has been suggested. But as of now increasingly many countries are stepping up to reduce their carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 This means that there will be a lot of demand for CSOs ESG (Environmental Social Governance) teams are gaining momentum on matters within the climate agenda like biodiversity and deforestation.

So, it’s likely there will always be a need for a CSO, but again, depending on the business model, the culture of institutions, the title might be different They may be called the head of sustainability There could be limited executive powers, but they will continue to be a central position, most probably- like a sustainability manager

Other

ess unstainable does not equate too sustainable Patagonia no longer uses the term Fashion companies should not be allowed to simultaneously profess their commitments to sustainability, while opposing regulatory proposals that deliver the same end Nike, for example, a brand that is committed to science-based targets, gets a poor rating from the ClimateVoice for lobbying (as a member of the Business Roundtable) against the Build Back Better legislation and its provisions to address climate change

Ultimately, businesses must disclose their lobbying efforts, use their status to affect positive change while engineering and improving their systems in place, so that they are regenerative To demonstrate progress stewardship reports should become mandatory, more quantitative focused, more in line with planetary thresholds and be subject to annual external audits

There is speculation within the fashion industry that some companies are guilty of “SDG-washing”, in other words exaggerating their contributing to Sustainable Development Goals, or cherry-picking goals that convenient for them to meet This is justified by the fact that fewer than 10% of companies who reference the SDGs in their reports actually have targets in place that measure their contribution towards them.

This was mentioned as an area of high interest to resolve amongst attendees of the annual Sustainable Textiles Conference hosted by Textile exchange (back in 2018), as there is certainly still a need to develop more discrete metrics that track progress towards SDGs overnments around the globe must work together to price negative externalities Carbon and water for example, should be taxed to include social costs This would most importantly discourage their use, lead to innovation and accelerate the adoption of renewable energy A governmental Committee in the UK has recommended a tax on virgin plastics (this covers polyester) The likely impact of such a tax would supposedly increase the price of synthetics, therefore making natural materials more attractive

This was mentioned as an area of high interest to resolve amongst attendees of the annual Sustainable Textiles Conference hosted by Textile exchange (back in 2018), as there is certainly still a need to develop more discrete metrics that track progress towards SDGs

Additional legislation really ought to be adopted to force fashion brands to share and abide by supply-chain commitments At present, the most recent groundbreaking legislation is the New York Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act that This mandates supply-chain mapping, carbon emissions reductions in line with the 1 5-degree Celsius scenario and reporting of wages compared to payment of a living wage

This is a state bill that affects fashion companies with operations in the state generating more than $100 million in annual revenue (includes brands from Shein and Mango to LVMHBrands with more than $100 million in revenue that are unable to live up to these standards would be fined 2% of their annual revenue Initially introduced in 2022, the bill was amended in November to include strengthened language The bill was set for enforcement January 2023

In the past, the UK’s governments proposals seem have been largely directed towards “ramping up action” around waste prevention to hold manufacturers accountable for textile waste The measures of the latest Waste Prevention Programme for England set out how the government and industry can act across seven key sectorsconstruction, textiles, furniture, electrical and electronic products, road vehicles, packaging, plastics and single-use items, and food to minimise waste and work towards a more resource-efficient economy

The UK government have proposed a new voluntary agreement for the fashion industry to reduce its environmental impact (launched April 2021); it asks signatories to commit to a reduction in their environmental footprints to meet set “science-based targets on carbon, water and circular textile by 2030 The programme also states that a producer responsibility scheme for the textiles industry could “boost reuse, better collections and recycling, drive the use of sustainable fibres, and support sustainable business models such as rental schemes”

These measures are all proposed alongside the Environment bill, which give the government powers to set minimum standards for clothing on durability and recycled content and explore ways to improve labelling and consumer information on clothing

But given that this a voluntary agreement and not legally-binding, it's hard to say whether businesses are actively committed to putting plans in place to meet these targets Since after a quarter century of experimentation with voluntary market-based win-win approach to fashion sustainability, it is time for a change Asking consumers to match their intention with action and to purchase sustainable, more expensive fashion is not working

Under the new plans, the UK government also announced that £30 million pounds has been allocated by the UK Research and Innovation to establish five new research centres that will develop UKbased circular supply chains, once of which will focus on circular textiles technology. The EU have also unveiled similar proposals to reflect efforts to advance the so-called ‘circular economy’ and promote consumer goods that are more sustainable, longer lasting and easier to repair and recycle

Under their plans (published March 2022) goods sold in the EU would be developed on a sustainability scale that demonstrates the product’s environmental impact, durability and how easy it can be repaired This mirrors the bloc’s current efficiency rating system for electrical appliances, which uses an A to G label to help consumers choose less energy-intensive products