3 minute read

Director's Report

Draining the Swamp How the Albemarle Region Was Formed (Not a Political Column)

Traditionally in the fall and winter, we celebrate the harvest by picking crops, such as soybeans, cotton, and peanuts. The region is blessed with soil composed of peat moss and sand from ancient swamp remnants of an ancient ocean. About 12,000 years ago, the ocean dissipated and formed the rivers of North, Pasquotank, Little, Perquimans, Chowan, and Roanoke, connecting and spilling into the Albemarle Sound. The end of the Ice Age was a formative time for North America, especially coastal North Carolina.

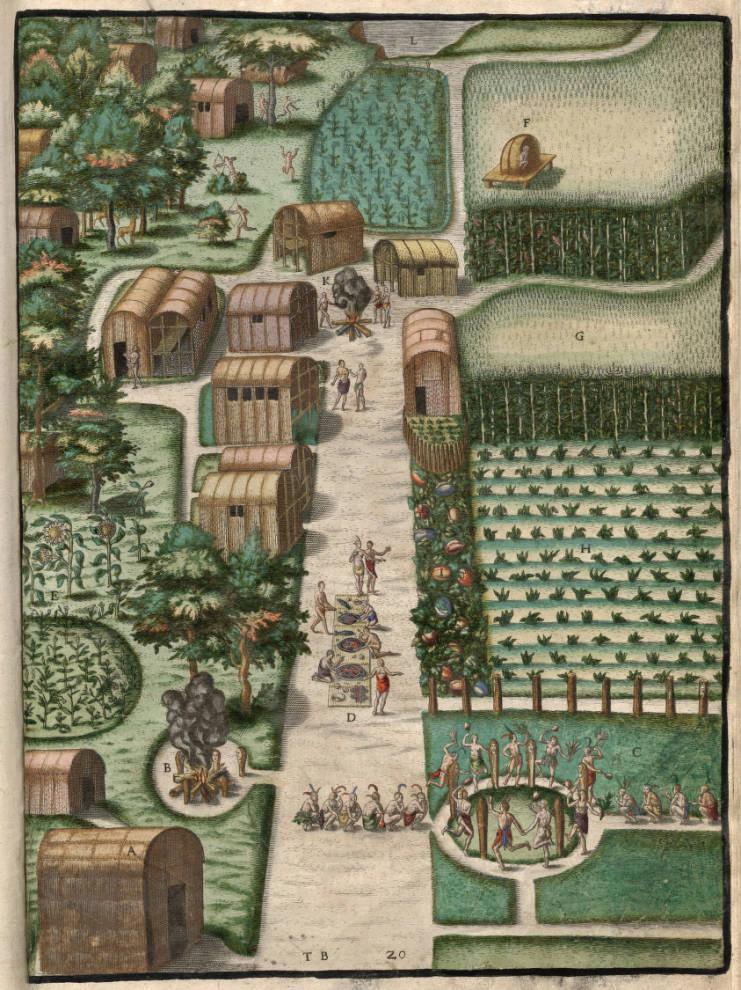

The primeval Albemarle was primarily a large inland ocean, a turbulent body of water stretching from Rocky Mount and flowing east into the Atlantic Ocean. The current had a force strong enough to push soil and sand into a delta, forming the Outer Banks. The Paleo-Indian tribes, who were nomadic hunter-gathers, would later follow the waterways and develop their societies into the Woodland culture on the lands that emerged as the waters subsided. These were the people who began farming the land and cultivating crops. Their basic staples were corn, pole beans, and squash; these were called the Three Sisters and were planted together. The corn was planted first to serve as an arbor, later the pole beans were planted at the base as vines and climbed the corn stalk. The last to be planted was squash. The large leaves blocked sun and photosynthesis preventing grasses and weeds from growing and depleting nutrients in the soil. However, they cultivated and grew one special weed for ceremonial and medicinal purposes, tobacco.

These are engravings by Theodore de Bry, who modeled his work after John White’s watercolors.

The Albemarle region is half land and half water. The Dismal Swamp remains as evidence of the slow process of draining. It was about two-thirds larger in area before settlers from Virginia drifted down and continued the farming traditions. They needed more land to produce table crops and tobacco—the precious cash crop that many say jump-started North Carolina’s economy and made the world take notice. The early founders went as far as to name the state’s capital after Sir Walter Raleigh, who popularized the use of tobacco by the English. Raleigh was instrumental in the beginnings of English colonization of North America. He never set foot on this continent but convinced Queen Elizabeth I to support and fund the First Colony and the great adventure that would become North Carolina.

The museum is poised and ready for the cooler weather with many programs for children and adults. Please come and visit us, participate in programs, or attend events and exhibits. We are celebrating Century Farms of Northeastern North Carolina. While you’re here you can Experience, Explore, and Engage with the past and enjoy discovering more about how we became us.

See you in the museum,

Don Pendergraft, Director of Regional Museums