11 minute read

A look at death in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Bruges culture

soetkin Vanhauwaer t

On 24 March 1487, a man called Boudin, residing near Vrijdagmarkt, was killed in a fight with a certain Lauwereins, while on 8 July 1488 Cornelis, the bell ringer at Sint-Salvatorkerk, fell from the church tower and died instantly. These are just two of many similar anecdotes contained in the manuscript Tghuene dat geschied es binner stede van Brugghe (‘What Happened in the City of Bruges’), showing that death was part of everyday medieval life. While plague and other epidemics raised mortality rates during certain periods, the high level of child mortality also meant that overall life expectancy was lower than it is today. Frequent wars and outbreaks of disease meant that medieval people were confronted by death in their communities. However, the tradition in which patients were cared for and died at home also made death a part of everyday life.

Advertisement

But death was not seen as the end: believers hoped for a new beginning in heaven, with the less fortunate going to hell. The notion of purgatory arose around 1200, where the soul would go temporarily after death to be purified of sin before being admitted to heaven. The soul’s ultimate destination would be decided during a personal examination at the Last Judgement. According to the Church, however, its destiny was still very much in the individual’s own hands, making it important to prepare carefully for the transition to another world.

Although death rates declined, this belief remained prominent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. People were still concerned about the fate of their souls after death, for which they prepared by simultaneously pursuing a good life – charity, prayer, confession, pilgrimages and donations – and a ‘good death’ – in the presence of a priest or relatives, and consoled by the last rites. It was important never to lose sight of that goal, and so a tendency arose in material culture to remind people of their mortality. This article discusses a number of Bruges art works in that context.

memento mori The idea of the transience of earthly existence was a powerful theme in painting from the fifteenth century onwards, but especially during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Donor Portrait of Margareta van Metteneye (c. 1525–30) shows the Bruges woman kneeling on a prayer stool, accompanied by a boy and by St Margaret in an imposing architectural setting. The rear of the panel, meanwhile, features a skull with worms, together with the stark message: Dat ghy zyt hebbe ic ghewest en dat ic ben dat zult ghy worden (‘What you are, I was, and what I am, you will be’) (Fig. 33). The fact that death is inevitable for everyone is here made explicit. The exhortation to pray for their own salvation and that of Margareta van Metteneye, thereby reducing the burden of everyone’s sin, is made plain in the words Bid God door my (‘pray God through me’) on the painting’s frame.

Similar ‘memento mori’ iconography can be found on tombstones from the same period. A skull and an hourglass can still be made out in a fragment from the tomb of P. Tristram (OnzeLieve-Vrouwekerk, Bruges), the former referring to man’s mortality and the latter to the fleeting nature of earthly life. The message is ‘Reflect on the fate of your soul and turn to God! Live well now, while it’s still possible.’ Skulls also feature in the iconography of several tombstones of nurses at Sint-Janshospitaal (Bruges, Hospital Museum).

the ideal death As previously stated, not only was an exemplary life an asset after death, the way a person died could also determine the fate of his or her soul. It was important to prepare for death by prayer, a final confession and receiving the last rites. Sudden death precluded all that and was thus widely dreaded. Medieval people believed that the sight of St Christopher would protect you on that day from unexpected death, while St Barbara would make sure you remained alive long enough for the priest to come.

A manual on how to die well was published in the fifteenth century. The Ars moriendi, as it was called, offered prayers and calls for reflection, together with guidelines on how to overcome temptations like vanity and despair in the hour of one’s death. In many cases, the texts were accompanied by encouraging pictures of temptations being defeated. The Bruges Municipal Archives have a fragment of a late-fifteenthcentury block book depicting the Triumph of Faith (Fig. 34). An angel, the Holy Trinity, Mary and several saints surround the bed of the dying man, while three vanquished demons flee.

The Death of the Virgin represented the ideal end in this period, thanks to four elements in the story, which is recounted in detail in the Legenda Aurea: firstly, Mary knew through divine inspiration that she was going to die; and secondly she was comforted by the presence of the Apostles. The third element comprised the prayers and psalms they read to her, while fourthly, they decorated her room with salutary symbols, such as incense and candles, to keep the influence of Evil at bay. Mary was thus able to die full of confidence, upon which Christ carried her up to Heaven. The image of the dying Mary, surrounded by grieving apostles, inspired many artists, who disseminated this notion of the ideal death.

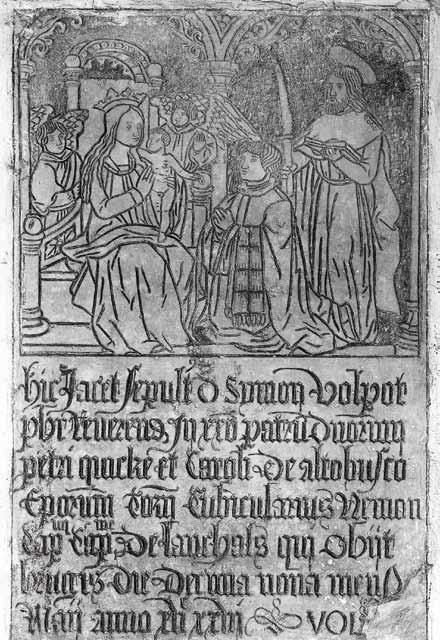

saints and memories Mary was not the only influential figure in the context of death – other saints too had a crucial part to play in the personal judgement of the deceased. Believers therefore sought to forge a link during their lives with a saint with whom they felt a particular affinity. Patron saints were especially popular in this regard. On his memorial stone (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, Bruges, c. 1526), the priest Simon Volpot is supported by St Simon (whom we recognize from the saw in his right hand) as he kneels before Christ and the Virgin (Fig. 35). This way, he hoped to receive not only Simon’s assistance, but also that of the Madonna as a reward for his eternal devotion. The memorial of Jan de Schietere and his wife (Sint-Salvatorkathedraal, Bruges, 34

c. 1576–77) likewise shows the couple in the company of their respective patron saints. They kneel at the foot of the cross, accompanied by John the Baptist and St Catherine, to show their devotion to the Passion of Christ in the hope of easing their own life after death. The donation of commemorative scenes like this to religious institutions was itself seen as conducive to salvation, and was a common practice in the period in question. Through such memorials, the dead continued indirectly to attract the attention of the living. This kept their memory alive and encouraged the faithful to pray for their souls, lightening

centuries, death remained a common factor. Everybody would die one day, and the already deceased did not hesitate to remind the living of that fact from their tombs and memorials. Death could strike at any moment, so it was advisable to be ready to confront one’s sins. ‘What you are, I was, and what I am, you will be.’

1. Circle of Lanceloot Blondeel, Donor Portrait of Margareta van Metteneye and Memento Mori, 1523, panel. Groeninge Museum, Bruges. 2. Anonymous, Triumph of Faith, late-fifteenth century, fragment of a printed book. Bruges, Stadsarchief, Oud Archief reeks 540. 3. Anonymous, Tombstone of Simon Volpot with memorial scene, 1526, limestone. Onze-LieveVrouwekerk, Bruges.

35

their own burden of sin and at the same time reducing the number of days the deceased would have to spend in Purgatory. Deathbed portraits, which appeared in the sixteenth century, were another way of preserving the memory of the deceased, who was frequently portrayed surrounded by symbols of his or her faith. Like several other nurses at Sint-Janshospitaal in Bruges, Barbara Godtschalk was painted on her deathbed, dressed in her nun’s habit and with her hands folded in prayer. There is a crucifix next to her and a burning candle – symbol of the Light of Christ. Paintings like this are precursors of the prayer cards that are still distributed at Catholic funerals.

Although society grew considerably more individualistic in the sixteenth and seventeenth

LENDERS Exhibition ‘From Surgeons to Plague Saints. Illness in Bruges in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’, Memling in Sin-Jan – Hospitaalmuseum 29 September 2011 – 26 February 2012

BELGIUM Mrs Rapaert de Grass Private collection Prof. Dr. Luc Baert Plantin-Moretus Museum/Print Room, Antwerp - UNESCO World Heritage Site Musea en Erfgoed Antwerpen Vzw Private collection, Antwerpen Bruggemuseum – archeologie, Bruges Brugesmuseum – gruuthuse, Bruges Groeningemuseum, Bruges Groeningemuseum, Prentenkabinet, Bruges Stadsarchief, Bruges Rijksarchief, Bruges Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek ‘Biekorf’, Bruges Klooster Hospitaalzusters van Sint-Jan, Huuse Sint-Jan, Bruges OCMW Brugge, Archief- & Kunstpatrimonium Archief Klooster van de EE. PP. Ongeschoeide Karmelieten, Bruges Kerkfabriek Sint-Walburgakerk, Bruges Kathedrale Kerkfabriek Sint-Salvator, Bruges Kerkfabriek Sint-Anna, Bruges Private collections, Bruges Dr. William De Groote, Bruges Bob Vanhaverbeke, Bruges PCB Penitentiair Complex, Bruges Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels U.L.B. – Musée de la Médecine, Campus Erasme, Brussels Collectie Museum Sint-Janshospitaal, Damme Stad Diksmuide Universiteit Gent, Museum voor de Geschiedenis van de Wetenschappen Stichting Jan Palfijn, Ghent Universiteit Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent OBK Openbare Bibliotheek, Kortrijk Privéverzameling, Kortrijk Volkskunde – West-Vlaanderen Vzw Antiek Pol Desmet, Wingene THE NETHERLANDS Privécollectie R. Butzelaar, Amsterdam Dr. Alphons Ypma, uroloog, Diepenveen Rijksmuseum voor de Geschiedenis van de Natuurwetenschappen en van de Geneeskunde ‘Museum Boerhaave’, Leiden Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

U.K. Wellcome Trust, Wellcome Library, London

U.S.A The Cartin Collection, Hartford William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History, American Urological Association, Linthicum

LITERATURE

800 jaar Sint-Janshospitaal Brugge, 1188/1976, Bruges, C.O.O., 1976 (exhib. cat., 2 volumes). Ariès, P., Het beeld van de dood, translation from French, 2ndedition, Amsterdam, 2003. Baert B., De vrouw van de toren. Omtrent de betekenis van de heilige Barbara in de traditie, in: Bovenaards en ondergronds. Het verhaal van Sint-Barbara 2006-2007, Cahier 2, Stad Genk, December 2006. Boelaert J.R., Zes eeuwen infectie in Brugge: 1200-1800. Leuven, ACCO, 2011. Boeynaems P. , ‘Broeder Jan Bisschop en zijn Pharmacia Galenica et Chymica’, Bulletin van de Kring voor de Geschiedenis van de Farmacie Benelux, no. 15, April 1957. Böhmer S. e.a., Von der Erde zum Himmel, Heiligendarstellungen des Spätmittelalters, Aachen, 1993. Broeckx M.C., Essai sur la médecine Belge avant le 19ième siècle, Ghent, 1837. De Meyer I., Origine des apothicaires de Bruges, Drukkerij Felix de Pachtere, 1842, Bruges. Deneweth H., Huizen en mensen. Wonen, verbouwen, investeren en lenen in drie Brugse wijken van de late middeleeuwen tot de negentiende eeuw (Brussels, 2008, unpublished doctoral thesis). Dewitte A., De geneeskunde te Brugge in de middeleeuwen, Brugge, Heemkundige kring M. Van Coppenolle, 1973. D’Hooghe C., De armenzorg te Brugge in de 17de eeuw, onuitgegeven licentiaatsverhandeling, RUGent, 1950. Geldhof J., De pestepidemie in Brugge, 1665-1667, Biekorf, 75 (1974) 305-328. L’initiative publique des communes en Belgique. Fondements historiques (Ancien Régime). 11e Colloque international Spa, 1-4 sept. 1982. Actes (Brussel, 1984) (Pro Civitate, Historische Uitgaven, Reeks in 8°, 65). Maréchal G., Het Sint-Janshospitaal in Brugge in de 18de eeuw. Aanzet tot vernieuwing? In: Handelingen van het Genootschap voor Geschiedenis 132 (1995)1-2, pp.5-60. Maréchal G., Het gebouw van de Brugse leprozerie in de XVIde eeuw. In: Biekorf 1979, pp.316-322. Mattelaer J., Le médionat, une tâche moins connue du barbier-chirurgien lors d’une exécution, Janus, Revue internationale de l’histoire des sciences, de la médecine, de la pharmacie et de la technique, p.137-147, 1974. Mattelaer J. Steensnijden in Vlaanderen in de 17de en de 18de eeuw, Geschiedenis der Geneeskunde, 1, Januari 1955. OCMW-archief, De bestanden Sint-Janshospitaal, Sint-Juliaan en M.Magdalena. Pannier R.A.C., Van gissen naar weten. De geneeskunde in Brugge in de 17de eeuw, de tijd van Thomas Montanus, Brugge, Van de Wiele, 2008. Spicer A. e.a., Defining the Holy. Sacred space in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Hants, 2005. Tussen hemel en hel. Sterven in de middeleeuwen, 600-1600 (tent. cat.), Sophie Balace and Alexandra De Poorter (eds.), Brussels, 2010. Vandevyvere E., Watervoorziening te Brugge van de 13de tot de 20ste eeuw (Bruges, 1983). Vandewiele L. J., ‘Enkele nieuwe gegevens over apoteker Jan Bisschop, Jezuïet’, Bulletin van de Kring voor de Geschiedenis van de farmacie Benelux, no. 50, maart 1975. Van Doorslaer G., Aperçu historique sur la médecine et les médecins à Malines avant le 19ième siècle, Mechelen, 1900. Vlachos S., Unerträgliche Kreatürlichkeit. Leid und Tod Christi in der spätmittelalterlichen Kunst, Museen der Stadt Regensburg, 2010. (Anonymous), Tghuene dat geschied es binner stede van Brugghe sichten tjaer ons heeren M.CCCC. ende lxxvij, den XIIII’ton dach in spurkelle. Manuscript 13267-13269, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Brussels.

Museum bulletin is a quarterly magazine of Musea Brugge, published by vzw Vrienden van de Stedelijke Musea Brugge

Responsible Publisher: Bertil van Outryve d’Ydewalle, p/a Dijver 12, 8000 Brugge

Coordination: Johan R. Boelaert & Sibylla Goegebuer

Copy Editing: Johan R. Boelaert

Editors: Johan R. Boelaert, Sibylla Goegebuer, Mieke Parez museumbulletin.redactie@brugge.be

Photography: Municipal Photographers Jan Termont and Matthias Desmet, Steven Kersse, Wellcome Library London, Raakvlak, Stad Diksmuide, Johan R. Boelaert, Albert Clarysse, Johan Mattelaer, Heidi Deneweth, Nico Insleghers, Museum Boerhaave Leiden, A. Leun, Archief & Kunstpatrimonium OCMW Brugge

Printer: De Windroos, Beernem

Translation: Ted Alkins, Heverlee

Musea Brugge Dijver 12, 8000 Brugge T 050 44 87 43 F 050 44 87 78 www.museabrugge.be musea@brugge.be

SPECIAL SUPPORTERS: