17 minute read

An Accompanying Career: Music in Partnership

The Accompanying Career: Music in Partnership

Editor’s Note: This excellent article was first published in The Triangle in the Fall 1976 issue and is as relevant today as it was then. Only minor updates have been made to the original story. The author’s original bio has been replaced with a current one.

Advertisement

An accompanying career opens the door to one of the most varied and satisfying areas in the music profession. Accompanying is an old as mankind — early man used drums to accompany his own voice — but not until Schubert, the innovator, did accompanying become an art. It is richly rewarding, ranging from the simple piano accompaniment to the higher levels of professional accompanying, vocal coaching, and chamber music. It demands special aptitudes, training, and insight. Success requires sensitive ears, a sensitive musical intellect, and last but not least, that repository of all human feelings — a heart.

Accompanying is a complex acquired art. It is partially true that an accompanist is born and not made, but the skills required for a successful career must be learned. Command of an exceptionally large repertoire ranging from the enormous song literature for all voices through solo and chamber music for stings and woodwinds to opera, oratorio and symphonic reductions comes only with education and experience. Guidance by others along the road to proficiency is important, but the initiative to learn must come from within the individual. Many of the necessary skills are learned by experience alone.

Choice of this career should be made with the firm conviction that accompanying is a highly worthy art. It should not be considered second best to solo piano performing. The role should be thought of as a partnership with the soloist, not as subservient to them. The field of accompanying offers the pianist who has never before worked in partnership with another musician a world of infinite variety and rewarding relationships.

DEVELOPMENT OF SKILLS

Not all pianists are good accompanists. There are differences in aptitudes, areas of concentration, and a frequent inability on the part of the solo pianist to play a more subordinate role. The early stages of development of the solo pianist and the accompanist are, however, alike: both must acquire highly refined technical skills in finger development and body movement — fluid finger dexterity and the right proportion of arm and body weight. Both must know how to use their instrument: the piano is a percussive instrument and at times percussive sounds are desired; however, it need not sound as if played with hammers. More often a warm, resonant sound is required, achieved by proper arm and body weight and by listening and thinking a singing line — molding the piano in a lyric way. The piano’s sound then becomes an extension of the accompanist’s inner thinking.

Although technical demands vary with the types of accompanying, a good technical foundation is desirable for all accompanists. While many vocal accompaniments do not require the highly developed technique necessary for solo instrumental accompaniments and chamber music, a mature accompanist must be prepared for all types of situations.

The technical equipment of the accompanist requires additional skills not usually needed by the piano soloist. A good accompanist must be an excellent sight-reader. Their mind must be alert to recognize instantly the patterns of passages written on the page and at virtually the same instant translate them into finger patterns. Playing large quantities of literature will help one achieve sight-reading proficiency.

In most instances sight-reading ability is more important to a professional accompanist than to a solo pianist, whose work generally culminates in memorization. Not so for the accompanist, who has less opportunity to become familiar with the music to be played. The rehearsal accompanist in particular is paid for proficiency in sight-reading. They should need only a little time to look over the music; a few seconds on each page should be sufficient to recognize difficult passages.

Other necessary skills include a working knowledge of transposition. Not all persons have the gift of transposing by ear, but transposition by clefs and by intervals can be learned through practice. An accompanist seeking to give full scope to his professional opportunities should also obtain experience in playing the harpsichord and the organ. There is often a need for a skilled harpsichord player in Baroque music. Even wider opportunities are open to organists.

Authoritative knowledge of styles is particularly important to an accompanist. The same elements that determine the style of a composition should determine its style of performance: melody, rhythm, and form, as well as type of composition (sonata, verse,

This photograph was taken in 1948, just after Ann Gibbens had won a solo competition. She was 16 years old.

program piece), composer (Bach, Schubert), and period (Baroque, Romantic). Differences in style cannot be learned from the study of a single composition; they are learned from comparative studies of the elements of music and the music itself. Performance style also includes the musical practice of the period at the time the composition was written as well as the musical practice of today. Accompanying vocalists poses special problems. When working with a singer, the accompanist must be confident in their knowledge of styles, texts, translations, and performance practices. The accompanist paints a picture in sound, evokes a mood inspired by the words. Failure to understand the text will make the accompaniment meaningless. Sound reaches the audience before the meaning of the text can register. We embrace the listener, infusing him with our feelings and concepts.

THE ROLE OF THE COACH

The extension of the accompanist role to that of a musical coach for singers and instrumentalists is relatively recent. Few accompanists possess sufficient pedagogical skills to qualify for the coaching role. The musical development of the accompanist and coach is the same. Their professional focus, however, is different. The coach has a teaching role, although it is not the same as that of a voice teacher. An accompanist may do some coaching, but usually in the short time of a few rehearsals. A coach works with a musician over a much longer period. The accompanist is primarily concerned with the finesse of his own playing, shadings of touch, and the give and take between the artist and himself. The coach concentrates on psychological, pedagogical and interpretative aspects of his relationship with the artist.1 Coaching requires a knowledge of repertoire and languages. Most often it involves training a singer for recitals and other performances, rehearsing operas, and choruses until the time of performance, when the conductor takes over, and less often the teaching of instrumental soloists. The coach guides and advises the singer in the development of every shade of dynamics, diction, nuances of interpretation and on occasion even stage deportment. They must be able to recognize every characteristic of the singer’s vocal instrument and suggest suitable repertoire to fit instrument and personality. Often, they are directly responsible for selecting the recital program. A coach’s temperament is important. It must be one that works well with singers and other musicians at all times in order to bring out the best in their personalities. Both coach and accompanist must approach the soloist with a cheerful, supportive attitude, which will encourage the soloist to be flexible and open to suggestion. Together, their efforts will lead to a high level of artistry.

Artistry in performance can be achieve to some degree at most levels of learning. Difficult to describe, it is a combination of

talent, personality, sensitivity, and style. Talent cannot be taught; it is inborn and can be only guided and nurtured. With sensitivity — the ability to incorporate feelings into art — there can be no artistry. Art can emerge from the anticipation of the soloist’s intentions, recognition of their strengths and shortcomings, and support of their fullest efforts.

RAPPORT IN PARTNERSHIP

The necessity for good rapport with the soloist cannot be over-emphasized. In the rehearsal studio the free exchange of ideas between accompanist and both vocal and instrumental soloists is important. Each gives the other psychological support and inspiration. A number of problems must be faced and resolved in rehearsal before a high-performance level can be reached. The sensitive accompanist is able to respond to the singer’s many moods, recognize their style, tempo, and concepts of the songs, anticipate where mistakes might be made, as in slightly varied repetitive patterns, and be able to adjust quickly to the singer’s errors. This responsiveness to the soloist’s needs must become almost telepathic. To develop acute awareness of these idiosyncrasies, an accompanist must play with as many soloists as possible. New problems constantly arise and the more varied the experience, the easier it will be to recognize and cope with them automatically.

Accompanying instrumentalists is more difficult and requires greater perception than accompanying vocalists because of the large number of solo instruments, the differences in their physical properties, and the subtleties and nuances of each. The instrumental accompanist should acquire a knowledge of the acoustical properties of the instruments — woodwinds, brass, and strings — their mechanical structures, fingerings, bowings. This can be obtained in several ways. One can actually learn to play the instruments, be a studio accompanist, or avail oneself of masterclasses and coaching sessions offered by other performing artists. In masterclasses, one gains insights into performance and instrument techniques as well as styles.

The relationship between accompanist and instrumentalist differs according to whether they are playing sonatas or instrumental solo literature. In sonatas there is total equality, but it is more difficult to overcome problems of technique, tone, color, blending and balance. Sonatas also require more rehearsal to work out nuances of shading and interpretation in order to reach an artistic level of performance. Partnership with a competent artist can be an exhilarating experience.

The playing of solo literature is different, as the accompaniment is often only the background for the soloist. This type of literature varies from virtuoso works to more sentimental and melodic pieces. The former is easier to play but requires that the accompanist be acutely aware of technical passages and variances in tempo if the accompaniment is to be flawless. The latter requires that the accompaniment match the tone quality of the instrument so that the two achieve a high degree of sonority together. In both chamber and solo literature, the accompaniment must be articulate and sensitive. Whatever the instrument, a good accompanist will learn by listening when to be subordinate and when to blend with the instrumentalist. Listening cannot be emphasized enough.

The greatest problem confronting an accompanist in performing with different instruments is the difference in balance and technique each requires. For instance, when playing with a cellist, the principal problem is balance. The cello, like a bass voice, can easily be covered and therefore requires accompaniment at appropriate dynamic levels. It is also easy for a pianist to cover the sound of the lower stings of the violin. When the violin is played on the much more penetrating higher strings, it is almost impossible for the piano to be too loud. Again, the ears of the pianist tell them how to accommodate the needs of tone, touch, and shading. A high degree of sensitivity to the subtleties of the string player’s bowings is needed, and more rehearsing is necessary to achieve unity of performance. With wind players, it is important to know the mechanical properties of each instrument and their resonating qualities. An accompanist must also be conscious of the wind soloist’s breath patterns so that the accompaniment can match their phrasing.

Perhaps the least appreciated task in this profession is the playing of piano transcriptions of orchestral reductions, frequently required for concert, opera, choral and dance accompaniments, where the piano substitutes for a large orchestra. Usually there are far too many notes to play, even for the best pianist, requiring the accompanist to make further reductions as he goes along. This requires that the accompanist know the original orchestral score in order to recognize the important lines that should be played.

THE PERFORMANCE

When the finished product is ready for performance, the demeanor of the accompanist becomes important to the soloist. Before going on stage, it should be one of confidence and quiet composure, which will give the soloist a feeling of security in the support expected as well as in his own abilities. The music should have been adequately prepared by both artists in rehearsals; concert time is no time for last minute changes by either. At all times, the accompanist should show steadiness, helpful to any soloist who is the least bit insecure. Balance of sound is primarily the responsibility of the accompanist. The problems are new with each performance: size of room and its construction properties, whether it is heavily draped, the carrying qualities of the voice or instrument in the room, and of course the individual characteristics of the piano.

Concentration is essential in order to anticipate any errors by the soloist and to avoid distraction by the audience. Playing the music should look easy. The accompanist’s appearance should be consistent with that of the soloist and the music. The audience will appreciate difficult accompaniments only if performed in good taste and in harmony with the mood.

Moments of great inspiration happen in performances that never happen in rehearsal. This is a very exhilarating experience. The true spirit of ensemble can be obtained when partners think of the performance in terms of the music itself instead of themselves in their individual roles.

CAREER OPPORTUNITIES

The opportunities open to accompanists are many and varied. Some of the full-time positions available are: (1) staff accompanist in music departments of colleges and universities, accompanying studio teachers, choirs and faculty and student recitals; (2) symphony pianist; (3) pianist for opera, dance studios and choral organizations; (4) work in the movie and television industries; (5) touring accompanist for artists (for the very few).

Part-time employment includes accompanying church choirs and local choral organizations, vocal coaching, and chamber accompaniment, and freelance and private studio accompanying.

This is only a partial list; the aspiring accompanist may find additional opportunities.

SUMMARY COMMENTS

The need for excellence cannot be stressed enough. Singers and instrumentalists should not be at the mercy of the accompanist. The accompanist should continually be taking advantage of opportunities to improve skills. Soloists rely upon the accompanist’s support both musically and psychologically. The accompanist’s contribution to the music profession is important.

These comments, it is hoped, may serve to guide young people aspiring to a career as accompanist, and to stimulate those in the profession to improve their skills. They may also provide criteria for soloists in search of an accompanist or those needing to evaluate their relationship with their present accompanist. In brief, the standard for a good accompanist is: (1) a good piano foundation; (2) the ability to listen intelligently; (3) an inquiring mind; (4) a vast and varied repertoire; (5) the ability to create good rapport and a partnership role; (6) knowledge of performance practices. Possession of all these qualities — those of a first-rate musician — make a rewarding career in the accompanying profession possible. 1 Kurt Adler, in his Art of Accompanying and Coaching, gives some excellent insights into the role of the coach and his or her relationship with the singer and instrumentalist.

FURTHER READING

There are few major pedagogical texts for learning the skills of accompanying. Some of the best readings are semi-auto biographical. Perhaps the best available sources include the following. Adler, Kurt. The Art of Accompanying and Coaching. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971. Bos, Coenraad V. The Well-Tempered Accompanist. Bryn Mawr, PA.: Theodore Presser Col, 1949. Lehman, Lotte. More than Singing. New York: Boosey and Hawkes, 1945. Moore, Gerald. Singer and Accompanist. New York: MacMillan, 1954. __________. The Unashamed Accompanist. London: Methuen and Col, Ltd., 1959.

To find a Mu Phi who exemplifies the fraternity’s spirit, one need not look further than Ann Gibbens Davis. She was initiated into the Phi Lambda chapter at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, on June 11, 1951, and has been steadily devoted to music and Mu Phi Epsilon ever since. In 1977, Ann made the motion at the 1977 convention to include men into Mu Phi Epsilon, which transformed the organization from a sorority into a co-ed fraternity. In addition to being an ACME honoree, Ann is the 2001 winner of the Mu Phi Epsilon Elizabeth Mathias Award.

Ann is a graduate of the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music with bachelor and master of music degrees in piano performance. Before coming to the Washington, D.C. area in 1973, she served as an accompanist and faculty member of California State University at Fullerton. For the past 46 years, she has had a successful career in the Washington, D. C. area as an accompanist, chamber music artist, church organist, teacher, lecturer and adjudicator. She has performed extensively on both coasts, including at the Kennedy Center and Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., Lincoln Center in New York City, and at mid-Atlantic colleges and universities.

Ann continues to stay active. She now resides at Fairhaven, a retirement community in Sykesville, Maryland, where as a new resident in 2015, she raised $17,000 for rehabilitation work on its Steinway concert grand piano. She performs and gives varied talks on Fairhaven’s concert series, and also works with Alzheimer’s patients through music. In 2009, Ann was inducted into the Maryland Senior Citizens Hall of Fame.

On October 31, 2020, Ian Wiese (Lambda, Beta, Boston Alumni) joined composers Adam Schumaker, Tyler Kline, and Benjamin Whiting on the release of Some Assembly Required, the debut album release by Boston-based mixed chamber ensemble Some Assembly Required. Wiese’s piece Machinations I for clarinet in B , horn in F, trombone, and piano, which was commissioned by Some Assembly Required, appears as the third track. Other pieces on the album include Kline’s Salt Veins, Whiting’s Formally Unannounced, Schumaker’s Click Here!, and SAR’s arrangement of Astor Piazzolla’s Four Seasons of Buenos Aires for Horn in F, Trombone, and Piano. The ensemble performers for Some Assembly Required are Justin Stanley, horn; Justin Croushore, trombone; and Cholong Park, piano.

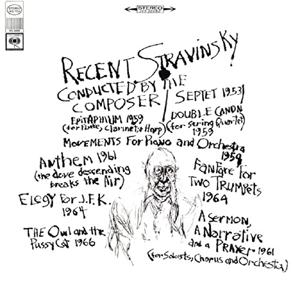

Congratulations to International Executive Secretary-Treasurer Jess LaNore, who was initiated into the Beta Psi chapter at the University of Indianapolis on Sunday, March 28, 2021, guided by 4th Vice President Rebecca Sorley and approved by 5th VP Terrel Kent. Adrienne Albert Adrienne Albert (Los Angeles Alumni) joined Ian Wiese (Lambda, Beta, Boston Alumni) on March 21, 2021, in a presentation and roundtable discussion to the Boston Alumni chapter on the composition and performance of three different settings of Edward Lear’s children’s poem “The Owl and the Pussycat.” The two composers discussed their settings of the piece as well as that of Igor Stravinsky (which Albert recorded for Stravinsky in 1966, along with Mass and Four Russian Folk Songs for mezzo-soprano, flute, harp, and guitar). Albert retold her history working with Stravinsky up through writing her own setting of the poem, and Wiese discussed how the two of them met through composer Jenni Brandon’s online workshop series “Writing for the Solo Instrument” in Summer 2020. The vocal ensemble Avimimus Duo (Alexandra Kassouf and Lauren McAllister) assisted the two in performing Albert’s and Wiese’s settings. The performance of Wiese’s setting was a world premiere. The original recording of the Stravinsky setting was played.

Jeanine York-Garesche Daniel Shavers Pamela Meyers

Jeanine York-Garesche, Mu Gamma, and Daniel Shavers, Epsilon Tau, members of the St. Louis Area Alumni presented a program called “How Teaching Music as Changed During the Pandemic” for the January 11, 2021. They were then asked by member Pamela Meyers, Epsilon Tau, to present the program for the AAUW (American Association of University Women) on March 13, 2021. Jeanine talked about virtual private music lessons and Daniel spoke about teaching public school band in different settings: totally virtual, in-person, and hybrid, which was a combination of virtual and in-person.