8 minute read

A Lifetime of Music and Joy

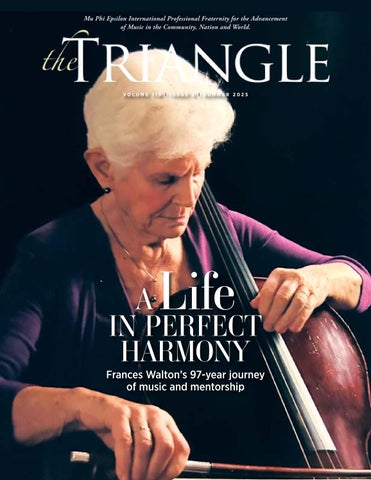

At nearly 100, conductor and musician Frances Walton plays on

By Dr. Kathryn A. Zufall

Frances Walton (Tau) is one of the most radiant, enthusiastic and gifted musicians I have ever met. When she comes into a room or lifts her baton to start a rehearsal, you just feel her great love of music shine through. Over her 97 years she has inspired many young musicians in the greater Seattle area and they still call or stop by to visit her — one from as far away as Norway, just a few months ago.

Walton spent the first six years of her life in Inglewood, Calif. When she was 6, Walton’s family moved to Tacoma, Wash. Her best friend’s father was the superintendent of music in the Tacoma School District. He discovered Walton’s talent for piano and put her on the radio.

“It made me feel wonderfully special,” Walton says. “I had the opportunity as a teenager of performing weekly on Tacoma Broadcasting and loved every minute of it. I could play anything of my choice — Chopin, Gershwin, Irving Berlin and the current operetta that was being rehearsed and performed at my high school, Stadium High School.”

Walton describes her role as pianist in the high school orchestra as “terrific fun” because it was her job to play the instruments that were not there. That meant transposing the trumpet and clarinet, both B flat instruments, and French horn, which is a fifth up or a fourth down, depending on the situation.

“There were infinite variables at my disposal,” she says. On stage, the singers and the dancers had memorized their parts, but the orchestra was reading printed music and learned to quickly transpose if the singers slipped a half step or a whole step. One night during a performance, the lights went out, and someone yelled “fire.”

Walton didn’t know if there was an actual fire, but there were only two small entrances to the auditorium which seated 5,000 people. So Walton decided to keep playing because she had memorized the score in case she needed to transpose or fill in other parts suddenly. The performance continued in the dark and because of that, the audience filed out of the auditorium very quietly and safely. “There was no fire,” Walton says. “But panic was aborted, and that was the big news.”

When Stanley Chapple — an assistant to Sergei Koussevitzky, the long-tenured music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra — came to University of Washington as the director of the School of Music, Walton was a conducting student in the master’s program. She was the only woman, but also the only pianist who could score read in any of the classes, so she had an opportunity to leap ahead of her classmates. Even though woman conductors were uncommon at the time, Walton displayed an aptitude for conducting that many of her male counterparts could not match.

She began to be known as a conductor for adults as well as youth in the region. She conducted the Bellingham Symphony, Thalia Symphony and Everett Symphony and was founding music director of Philharmonia Northwest — the first chamber symphony in the Pacific Northwest, established in 1976. “I think amateur musicians are the most extraordinary and most unique and a joy to work with,” she says.

When Walton started the Eastside Youth Symphony in 1964, which became the Bellevue Youth Symphony — “a lot of kids wanted to be on the ski slopes on Saturdays” — at the same time that the Seattle Youth Symphony was rehearsing. But they could participate in the Bellevue Youth Symphony which practiced on Monday nights, also playing smaller orchestral literature like Mozart, Beethoven or Brahms.

“It was a wonderful opportunity,” Walton says. “I loved it and I loved learning right along with the kids. I look back on it with a huge smile. I think I’ve had more fun than I ever had in my whole life learning scores and studying right along with my wonderful youth symphony and their desire to learn. We started with Beethoven Symphony No. 1 and went right through and three years later we were playing Beethoven No 9. What a journey.”

Musical Roots

Walton’s mother grew up in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, a mining town in the eastern part of the state. After school, she waited for the miners, who were mostly Welshman, to come up from the mines. Although they were tired and weary, the men always sang and Walton’s mother noticed that it wasn’t in two or three part harmony, but eight to 12 parts. The miners always managed to find their pitch, and it was remarkably complex.

“My mother was a self-taught pianist and had the kind of ear that could hear a complex tune once and play it immediately,” Walton says. “When I was a child, her piano playing and singing didn’t seem like anything unusual, except when I had birthday parties. After the wonderful lunches of spaghetti and meatballs, the biggest part of the party seemed to be gathering around the piano and singing camp songs.”

Her mother’s complex harmonic development caught Walton’s ear immediately and she thought maybe she could also play piano that way without reading any music. Walton did so until she reached the third grade and fell in love with Debussy. “I could sing the whole tone scale but it didn’t fit into the well-tempered scale,” Walton says.

“So I asked Mom if I could have piano lessons for a way out of this dilemma. She said ‘sure’ and I ultimately studied for many years with Leonard Anderson.”

Walton’s parents encouraged her to attend a liberal arts college, and she chose Washington State University in eastern Washington. In college, she entered the Greater Inland Empire Competition, winning first place with the Chopin F Minor concerto. During the performance following the award ceremony, Walton remembers blanking out and realizing she was unaware of what was going on. She kept her left hand going with the orchestra and eventually, her right hand caught up.

“The conductor, Paul Waelan, took a big red handkerchief out of his back pocket and wiped the sweat from his brow,” Walton says. “I was mortified, but thankful that I finally found my way out of this black hole. Talk about learning from your mistakes. I learned that I could fight my way through and come out the other side. It was a great feeling to know that I could survive and not let the musicians and the composer down.”

Of all of her performances, one that Walton remembers fondly occurred on board ship in the middle of the South China Sea. She was a passenger on a holiday cruise and there happened to be a band with a Steinway B grand piano on stage. One afternoon when no one was there, Walton took a chance and played to her heart’s content on the piano. That evening, the announcer asked Walton to come on stage and play Clair de Lune by Debussy.

“I was so surprised,” Walton says. “I leapt at the chance and got on stage and started the magical beginning. The audience hadn’t expected it. I didn’t expect it but it was a moment of sheer joy, and it was a wonderful listening audience. It’s really true that there is a trinity of music: the composer, the performer and the audience, three equal and caring parts. That night, Debussy had it all — and so did the audience and I.”

Although she no longer conducts symphonies, at age 97, Walton still plays cello in a string quartet that’s met weekly for the past 35 years. As she reflects on her life, she can’t help but be grateful for the role music has played in enriching her years and serving as a catalyst to forming lasting relationships. Though the Seattle Alumni chapter of Mu Phi Epsilon has been inactive for years, Walton remains a proud life member who cherishes her memories of music and the friendships forged through shared musical adventures.

“I have loved this world,” Walton says. “And will never ever be sorry that I was a part of it. I am so grateful that God has bestowed this gift of music on this humble lady.”

_________________________________

Kathryn Zufall, MD, grew up in New Jersey playing violin in a string quartet with her sisters. Zufall was a medical intern in Seattle in 1979 when her violin teacher introduced her to Frances Walton. Over the next decade, Zufall married, had three sons and worked about 60 hours a week in her internal medical practice with little time for music. Once her youngest reached kindergarten, Zufall reconnected with Walton, who has been a great mentor and inspiration to her ever since. They have played concerts together and still play string quartets every Wednesday with friends. Walton shares a special place in Zufall’s family and has played at her sons’ weddings. Now retired, Zufall has even more time for music and her seven wonderful grandchildren.