10 minute read

FireBlade FireBlade Forging the Forging the

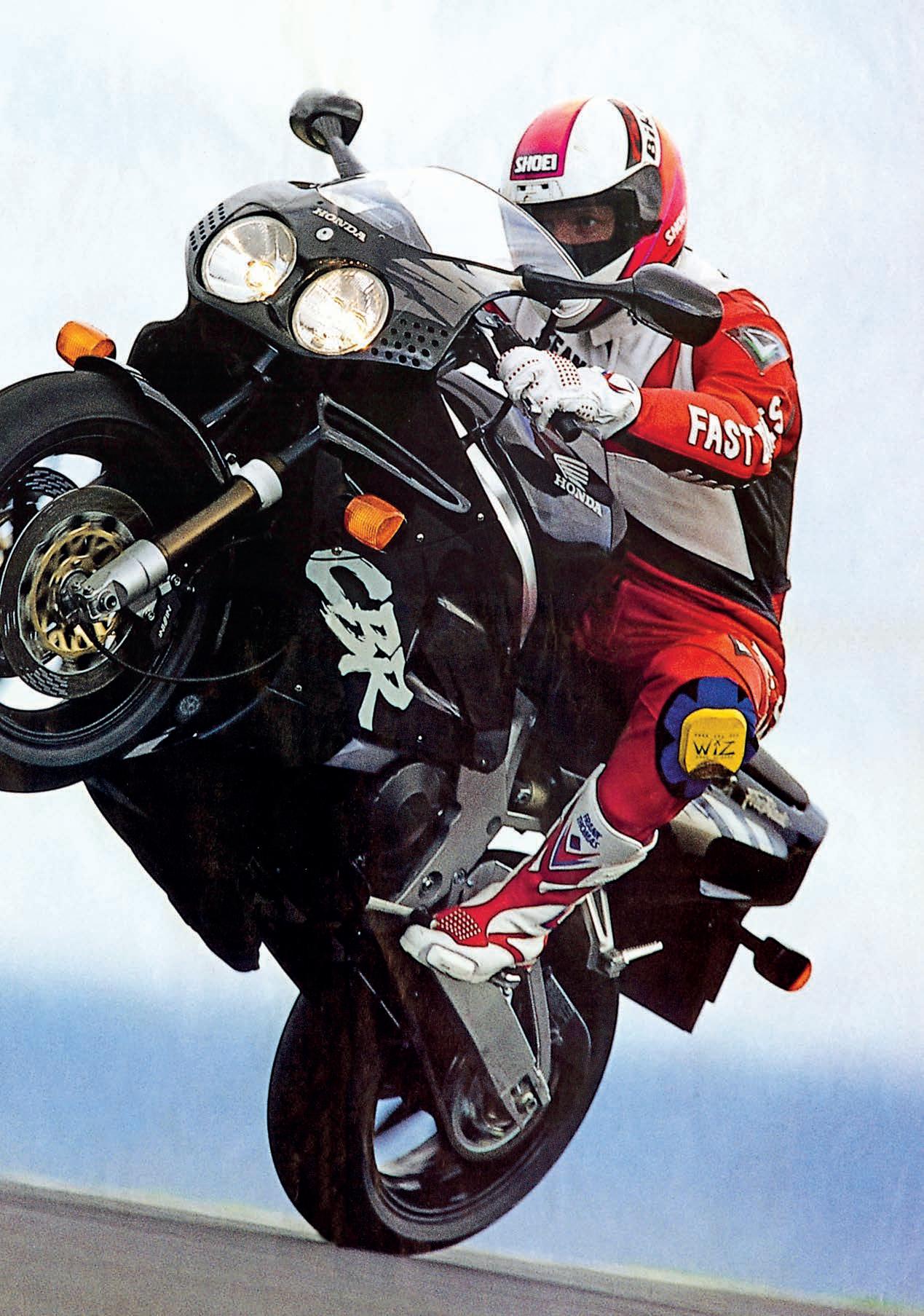

Testing, testing, testing: it’s almost never-ending. This is Suzuka race circuit and it’s 1989.

This legendary Japanese circuit that has echoed to the sounds and seen the sights of legendary Formula 1 car events and 500cc Grand Prix races now reverberates to a more solitary sound.

Advertisement

The sound is unmistakably a four-stroke; it’s clearly a four-cylinder machine of 700-900cc or so of capacity, but the crude sand-cast metal parts, movable engine mounts, strange tank shape, fairing and chassis parts of indeterminable origin and overall shoddy finish do not tell you that this machine is an early pre-production version of a bike that will become a new byword for street motorcycle performance.

Occasionally the single machine is joined on track by one or two other machines. These are much sleeker, more polished, the finished items no less. These are the current crop of litre-class sports bikes: Suzuki’s GSX-R1100, Yamaha’s FZR1000 EXUP, Honda’s own CBR1000F and Kawasaki’s blisteringly-fast ZZ-R1100. Compared to its peers, this development Honda looks ugly and yet feels purposeful.

Every so often this grotesque machine pulls into the pits and stops in a garage.

Almost immediately the rider is swamped by technicians wearing the ‘flying wing’ motif of the mighty Honda corporation. They interrogate the rider about engine performance, handling and braking: everything is noted down. Engine position, suspension set-up, then the rider is asked how the motor felt, what were the tyres like? Any scary moments? Did the seat feel comfy? Everything and then some: still buzzing on the adrenalin of riding the challenging and scary Suzuka circuit, the test rider answers the questions as best he can.

Changes are made and the bike accelerates out of the pit-lane and goes back out on to the track. Security is tight. There aren’t any cameras and certainly no smart phones to instantly leak spy pictures to the internet.

That bike burning up the track back in the late 1980s is an early ancestor of the Honda CBR900RR FireBlade and the later CBR1000RR Fireblade and over the next 25 years it will become the machine by which all other sports bikes are to be measured, but let’s start at the beginning and check out this little fellow. One of the technicians isn’t wearing any overalls; he’s in leathers. He’s Tadao Baba – chief engineer for Honda Research and Development. This is his first bike as project leader and the scuffs on his leathers tell you that he takes his work very seriously indeed.

It’s fair to say that – for a Japanese man and Honda executive –Baba-san is a maverick. You’ll spot him in the pits sitting on a large fuel drum, puffing away at one of his 20-a-day cigarettes. You’ll see him out on track riding hard – and fast – and then crashing when he pushes just that little too far. But Baba-san has been around the block a few times and in a time of 80s excess where bigger is better and bigger and faster is better still, he has a plan.

“Bikes at the time in the 1980s were very fast. WHOOSSH,” Baba mimes with a smile on his face, making his hand shoot upwards, like a rocket. “But I felt they never turned like a race bike, there was no ‘flickflack,’” he again holds his hand up to show what he means, this time bringing it down in a chopping motion then mimicking a bike flicking through a chicane as he makes his hand move from the vertical to the left then quickly back upright and swiftly down to the right. “You see, I wanted a bike that would be good into the corners, which produced good power and had good brakes.” He adds: “The CBR900RR made its debut in 1992, but it took us more than three years to reach that point.

“At that time, the Japanese market was full of race-replicas, such as NSR250 two-strokes and CBR400RR four-strokes while in Europe the power war had started with the Kawasaki ZX-10, GSX-R1100, and our CBR1000F. Up until then we called these bikes ‘super sport’, but, I thought ‘wait a minute, are these big and heavy bikes really ‘super sport?’ I thought that going down a straight at high speed doesn’t mean ‘super sport.’ As it is a sport bike, it must be sporty. The performance must be fun, easy and quick to control.

“A sport bike should be controlled freely as to the rider’s wish. In this aspect, all those big monsters were not good enough to be called a sport bike. Yes, they were fast, but, heavy and to my mind they were quite dull. We realised that we should create a completely new, enjoyable world for sport bike lovers. We knew we must go back to the first place and start again. We wanted to give riders something over which they had ‘total control.’”

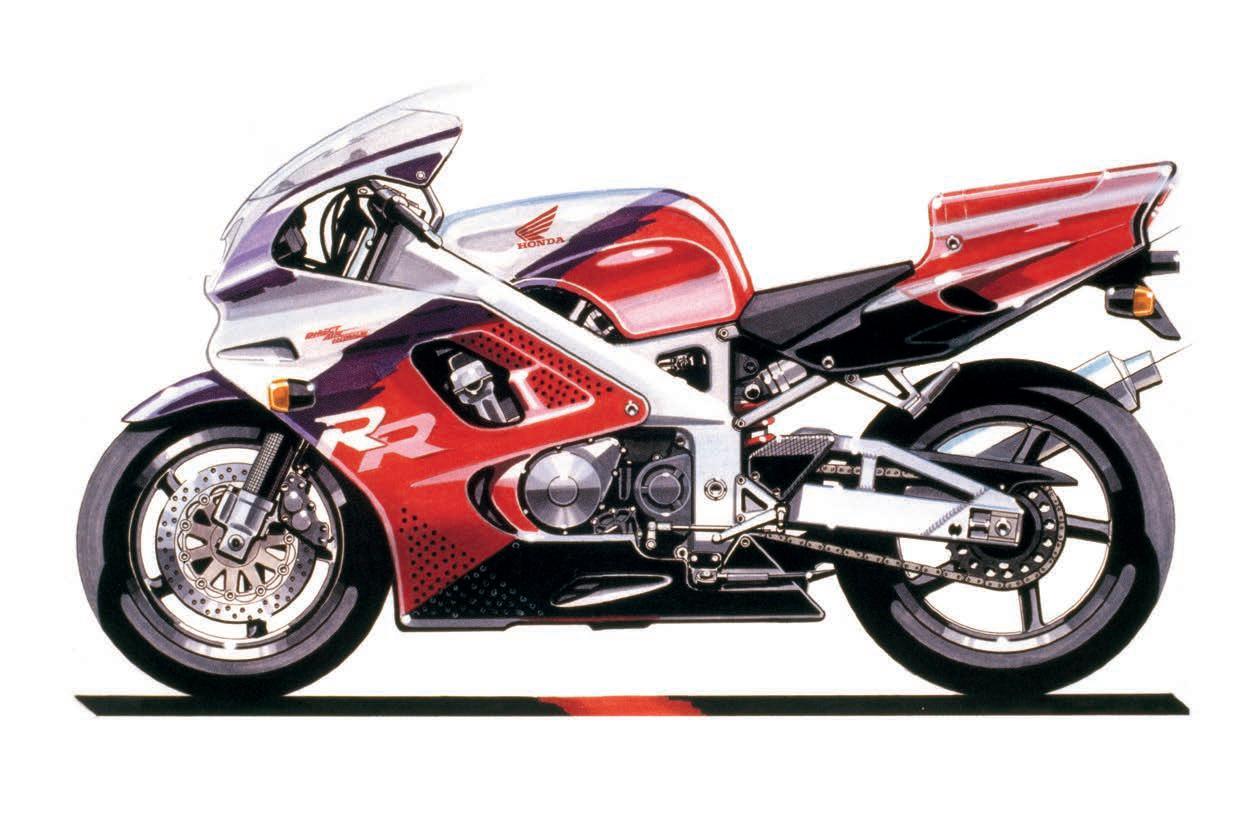

Total control: these two words would come back again and again as what became the Honda FireBlade was developed over the next quarter of a century, but what of Honda’s existing big-inch sports bike of the time? Initially the CBR1000 was marketed as a ‘super-sport’ bike. But since its release in 1987 it had transformed itself from a cutting-edge sports machine into a more laid back sports tourer. Baba-san explains: “As the CBR1000’s development proceeded, we had to think of practical aspects, such as riding long distance on an autobahn comfortably, taking a passenger on the pillion seat and so on. Then, it became more like a touring bike, but with sporting pretensions. We wanted to keep it a bike that people could use on twisty roads and sweeping corners, but its ever increasing weight made it impossible to make it a real sports bike. So, from those ideals came the start of the concept of the CBR900RR FireBlade.”

At the start of the FireBlade story then, it was all about-face as the impetus for the machine came from research and development rather than the marketing department. Initially the marketing men would find some new area to exploit and brief the R&D team to make a product that was suitable – not so with the new CBR-RR.

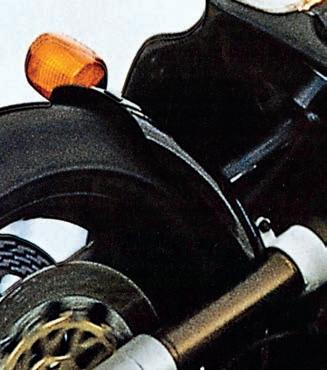

ABOVE: The new model CBR900 wasn’t an ‘F’ but a full-on ‘RR’ racereplica, as shown on this marketing diagram.

At the earliest stages of the development, the leader of the project was Yoichi Oguma. Oguma-san was from Honda’s racing division –Honda Racing Company or simply ‘HRC’. This showed you where the driving force for this project came from, but – thankfully for us – this machine wasn’t going to be designed as a sports-production or ‘homologation special’ as the final capacity was not going to be suitable for production racing rules of the time. After just six months of driving the project forward, Baba-san took over and this was to be his first time in overall charge of a project. By this time it was to be a no-holds barred super sports machine, not with the ‘F’ road bike suffix, but the ‘RR’ race designation.

“At this time,” recalls Baba-san, “it was still before even an egg of the FireBlade had been made! We had only a very rough idea of what we wanted and very little design had been done, so the first step was to refine the idea and decide the machine lay-out. It was a very exciting appointment for me at the time. I knew the project would become very

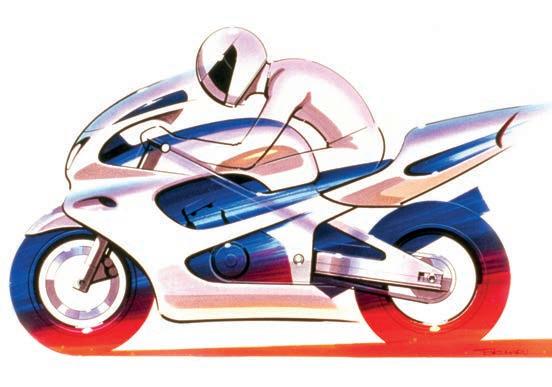

ABOVE: Early development sketches hinted at the race-oriented nature of the bike… important for Honda. So I was highly motivated to make this machine a complete success. Of course I was nervous! But I was pretty confident, too, as I knew my strong points and weak points from my experiences at Honda up until then. I love riding an out-and-out sportsbike, and I love to feel satisfied when I can control it as I want to. I knew my strong lust for conquest would lead the project in the right direction.”

For Baba-san himself, this was the beginning of arguments, stress and sleepless nights as he strove to make a bike with plenty of power and light weight – this final fact being what he felt was the real key to the project. “I was happy to get this project – very happy, but the development life of the CBR900RR was not always so cheerful. I suffered a lot: we all on the development team suffered a lot! Many times we got very, very stressed out and often worked long hours through the night to achieve our goals.”

Obviously, Baba’s inexperience in leading a whole project team made the task more of a challenge, but he felt he knew what he wanted from each individual in the team and the contributions they could make to the final product. “Most of the engineers were younger than I was,” he remembers, “but, they all had different backgrounds to be the particular specialists on chassis, engine, suspension or whatever. I respected their thoughts and ideas and always listened to them. I understood that my work was to gather their best ideas and to bring them together as a whole product. A good engine doesn’t sell a bike. Nor does a good chassis, you have to bring these great ideas into a whole that must gel together: that’s the secret.”

BELOW: Later, more detailed sketches showed the DNA of the original bike we know and love today.

ABOVE: Honda’s CBR1000F was a good sports-tourer – but no out-and-out sports machine.

Professional conflict with other members of the team cropped up from time to time, as (understandably) long nights and a high stress environment took its toll. “Rumours began to circulate,” smiles Baba. “These rumours were that the young engineers would complain that when it came to cutting the weight of a component, ‘Baba-san never says yes.’ Apparently the young engineers used to call me ‘Hotoke no Baba’ or Buddha Baba in English, maybe because I always thought I was right,” he laughs. “Despite that, I could be like a thunderstorm when I got angry. Maybe, some of them were afraid of me – maybe they still are? It’s because I can never let myself compromise – and we couldn’t compromise on the weight of the CBR. I guess I am pretty stubborn! I think aging has made me milder, but others may not agree.”

Also, after years in a test position where he could tell engineers what was good or bad about their product, for Baba the boot was now on the other foot and he had to listen to what the test team said about his machine and sometimes this made things difficult. “Before, as a tester, I used to shout at the engineers when they made me ride a dangerous test bike. ‘How could you let me ride such trash?’ I would say, but, suddenly, there was no more shouting.” At the time the full specification for the machine that would become the FireBlade was still not pinned down.

At first, the FireBlade project was most definitely a 750cc across-theframe four-cylinder – despite initial denials that it was always going to be a new cubic capacity class of motorcycle. Pictures later discovered would show a motorcycle closely aping the look of the CBR400RR TriArm. “Ah yes first the FireBlade was a 750,” recalls Baba. “This was what we made at first, but then we thought ‘we already have a VFR750, why not make it a 1000?’ But then to make the FireBlade 1000cc would put it against the CBR1000F. Instead we thought we would make a new class of motorcycle: something unique. This is what we decided to do.”

At the second Honda FireBlade Day in 2008 (or should that be Fireblade – as the bike lost the capital B as it went to a full litre-spec in 2004) Baba-san sat with me and explained how he and his team came up with the specific capacity of the original model FireBlade. “Okay, so why 893cc? Look at this,” Baba-san was sketching out a profile picture of a sports bike – the CBR750RR. “We literally took the original measurements of the CBR750RR: wheelbase, castor, trail, everything and then looked at the motor, what could we do with it to make it better? We realised that if we kept the bore but stroked the motor we would get 893cc – and that’s why it became that cubic capacity. We found that the 750 had good top-end power, but with 893cc we also had good torque. This was a big advantage for us.” And this is what helped give the FireBlade its real advantage both on track and street: many of the test riders would get off the FireBlade mule and complain that it didn’t feel that quick compared to the other machines, only to find that the stopwatch told a different story.

“Our main aim was that – first of all – we wanted to build a big sports bike which was actually lighter than a 600cc model. Then, to gain the right stability for the machine, the chassis dimensions and riding position were fixed during our extensive testing. So, at the end of all this we find that there is a limited space for the engine. As I mentioned, with the space we had left we thought we could go for something bigger than 750cc hence we managed to get an 893cc powerplant.

“We really wanted a motor that could push this bike to around 161mph (260km/h) – that would be enough! From this data we could find exactly what maximum power we would need for the bike to get to this speed and from there what the displacement of the motor would have to be. That turned out to be 893cc, stroking that original motor. Obviously in later years we would up the displacement to more than 900cc. Like the drop in weight, we found we could squeeze more from the powerplant also.

“But at the beginning we chose the layout of the best machine from a number of different options, they were not so different as the direction was the same and the ideal point was the same: optimum power with as little weight as possible. We had to decide where to draw the line, where we stopped scrutinizing each individual part. It was a big hurdle to go over at first, but with subsequent models of the original 900cc FireBlade we managed to mature the product little-by-little.”

Development Goes Global

It was early in the test schedule in 1989 when Dave Hancock from Honda UK became involved in the project. He was one of three

European test riders, the others being Bernard Rigoni from Honda France and Klaus Bescher from Honda Germany, who would test Honda’s latest creations in their varying forms throughout the test programme for their suitability in the European market. Honda USA and Japan had their own testers, mainly for reasons that many models for those parts of the world were pretty much for those markets only, such as the 400 four-stroke class in Japan and the big cruiser market in the USA.