10 minute read

Minneapolis, MN 55404 YOU MUST RESPOND TO EACH CLAIM. The Answer is your written

TV fiction depicts backlash women face while running for highest office

By Karrin Vasby Anderson

Even before Democratic Presidential candidate Joe Biden named Sen. Kamala Harris as his VP pick last week, his promise to name a woman running mate had already prompted familiar debates about gender and power.

Are these potential vice presidents supposed to be presidential lackeys or understudies to the leader of the free world? Should they actively seek the position, or be reluctant nominees bound by duty?

After Sen. Kamala Harris’ name emerged as a short-list favorite, CNBC reported that some Biden allies and donors “initiated a campaign against Harris,” arguing that she was “too ambitious” and would be “solely focused on eventually becoming president.”

Claiming that people who want to be president make bad vice presidents might seem illconceived if your audience is Vice President Joe Biden. And pundits and journalists quickly pointed out that the argument was racist and sexist—like, really, really sexist.

So why were Democratic Party insiders spouting it?

One clue can be found in the way we tell stories about women politicians. In our book, “Woman President: Confronting

Postfeminist Political Culture,”

Film Review: By Dwight Brown

Decades ago, long before BLM protesters marched and chanted “George Floyd—I can’t breathe,” demonstrators shouted, “Yusuf. Yusuf. Yusuf. No justice, no peace!” Racially motivated crimes that ignite outrage have a long history. One of the most heinous felonies provides a back story to today’s struggles.

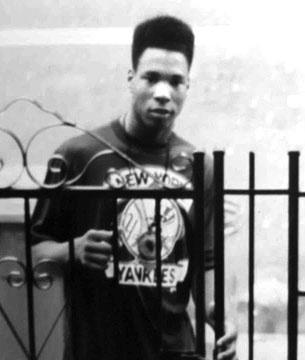

On August 23, 1989, Yusuf Hawkins, a 16-year-old Brooklynite from East New York, traveled to the unfamiliar Brooklyn neighborhood of Bensonhurst with friends contemplating the purchase of a used 1982 Pontiac.

Unbeknownst to him the largely Italian American community was hostile to Blacks. Some male teenagers misidentified him as an interloper there to meet a White homegirl, Gina Feliciano, and attend her birthday party.

Gina’s acquaintance Keith Mondello, angered by the invitation she supposedly extended to Blacks and Latinos, formed a mob equipped with baseball bats. They surrounded and attacked Hawkins and his buddies. Two gunshots rang out. Two bullets hit Hawkins in his chest just inches above his heart. It cost him his life.

At the time, New Yorkers were weary and stressed by similar racially motivated deaths: MTA worker Willie Turks in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn in 1982; Michael Griffith in Howard Beach, Queens in ’86. Hawkins’ murder was a last straw.

New York viewers who lived through this tragedy and its aftermath will have their memories refreshed by flashbacks of a divided city, a divisive mayor, an insular predominantly White neighborhood and a Black community in the hunt for answers and convictions. Those unfamiliar with the case will be shocked by the eerie similarities between protests of yesteryear and now.

Filmmaker Muta’Ali Muhammad’s (“Life’s Essentials with Ruby Dee”) documentary focuses on a pivotal time in New York City’s history and includes an impressive set of interviews with many of those connected to the event, its consequences and Hawkins’ legacy. Footage is split

Yusuf Hawkins family photo

between ’89-‘91 around the time of the murder and trial, and 30 years later when those involved reflect on their mission.

The time capsule captures the height of the turbulent ’80s, from the dubious posturing of Mayor Ed Koch to the volatile atmosphere surrounding the Central Park jogger incident in April of 1989. NYC city is boiling over with Black vs. White tension. Add in four Black youths being victimized by a White mob in an outer borough, and the summer of ’89 was ripe for drama of Shakespearean proportions.

Muta’Ali Muhammad’s approach to reconstructing the time and era is so thorough it makes up for his very traditional documentary style: New and old interviews, newspaper clippings, archival newsreels, family photos. Visually, his saving grace is a fairly eye-catching series of overhead shots of the Bensonhurst neighborhood, the corner where the murder took place and the Snack & Candy store involved.

The effect looks either computer-generated or like aerial drone footage tricked out. Cars seem like toys driving around fake buildings. The arresting images become increasingly powerful as they are repeated, sometimes with red dots tracking the movement of the adversaries as they attack the unsuspecting victims.

Equally impressive are the people who define their roles in Hawkins’ life, the incident and its aftermath. His mom Diane, brothers Amir and Freddy, sister and friends describe what it was like to be pulled into a firestorm, particularly as they marched through the riled enemy territory of Bensonhurst and were bombarded by racial slurs and death threats.

The thin nattily dressed and astute Al Sharpton of 2020 compared to the overweight, showy and not always prudent Sharpton back in the day is a bit startling. Sharpton: “Every time a Black man comes to the bar of justice, there’s no justice.”

Hearing from 90-year-old Mayor David Dinkins on how he handled NYC’s racial tension versus the very rambunctious Koch is enlightening. An interview with Russell Gibbons, a young Black man who lived in Bensonhurst and hung out with the White gang the night of the homicide, will surprise many. What’s it like to be in his shoes?

Perhaps the most impressive persona is that of Hawkins’ father Moses Stewart. Only months before the incident, the estranged dad had reemerged. It’s as if fate sent Hawkins a guardian, not so much for his life, but for reparations. Hastily, Stewart transitions from a crestfallen father to an increasingly savvy activist learning how to work the press and give fiery speeches.

If you’ve ever wondered how “everyday” people thrown into the midst of public tragedies compose themselves, adapt and navigate through media storms, Stewart is the archetype. Stewart: “You don’t know what you’ll do until something happens to you.” Which is why watching this film is so haunting.

It’s like eyewitnessing a car crash, going into shock and living through the outcome. And if you are an African American viewer, some part of you has to acknowledge that the tempest that struck the Hawkins family could strike you, too. Just as it did the families of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and now George Floyd.

Why did the NYPD ask the Hawkins family not to publicize their son’s death? How did Bensonhurst’s Mafia ecosystem influence an arrest? What happened to Mondello, the batwielding mob and the killer? Who attempted to assassinate Sharpton? The film answers questions you couldn’t conceive.

Hawkins walked into a nightmare. This is what happened to the life of one who is pure to save behind. Has that happened?

Thanks to Muta’Ali Muhammad’s thought-provoking documentary, Hawkin’s family, friends and supporters are no longer defined by the tragedy

create a “likeable” woman presiJulia Louis-Dreyfus winning six dent, they go out of their way to consecutive Emmy Awards for demonstrate that pursuing the her burlesque send-up of the fapresidency isn’t her life’s goal. miliar female trope. The women presidents Interestingly, both “24” and in “Commander in Chief” and “Homeland” have important con“Battlestar Galactica” didn’t camnections to real-world presidenpaign for the office. They ascendtial politics. Both series portray ed to the presidency as a result of the first woman U.S. president as tragedy. In the former, the presia veteran politician and middledent dies of a brain aneurysm; in aged White woman. They bear the latter, a nuclear attack takes strong resemblances to the only out the first 42 people in the presiwoman who has been a majordential line of succession, leaving party presidential nominee: Hillthe secretary of education to fill ary Clinton. Appearing in 2008 the role. (To be fair, this did seem and 2017, respectively, the stolike a woman’s likeliest path to rylines were clearly planned to presidential power in 2004.) Each coincide with what could have Sen. Kamala Harris has been attacked for trying to character is portrayed as an ethibeen Clinton’s first term as U.S. climb too high. AP Photo/John Locher cal and effective leader—not perpresident. fect, but plausibly presidential. Yet depictions in “24” and Conversely, series like “24” “Homeland” of fictional women communication scholar Kristious are presented as less trustand “Homeland” feature wompresidents align with commutina Horn Sheeler and I examine worthy than those who don’t en candidates who aggressively nication scholar Shawn J. Parryhow fictional and actual women actively seek the presidency. seek the presidency. In both Giles’ findings that the media presidential figures are framed There have been seven series cases, the women start out as framed Clinton as inauthentic, in news coverage, political satire, on U.S. television that follow a principled politicians, but their Machiavellian, and ultimately, memes, television and film. woman president for at least one true nature is revealed as weak dangerous.

Our close reading of these full season: ABC’s “Commander and duplicitous. Their presidenThat brings us back to our rediverse texts reveals a persistent in Chief;” the Sci-Fi Channel’s tial tenures end up being ruincent veepstakes. backlash that takes many forms: satirical cartoons that deploy sexWomen who are politically Criticisms of women vice presidential prospects echo culist stereotypes; the pornification of women candidates in memes; ambitious are presented as tural scripts that insist women who want to be president and news framing that includes less trustworthy. shouldn’t be trusted. Undermisogynistic metaphors, to standing the resistance to Harname a few. “Battlestar Galactica;” Fox’s “24;” ous for the nation, and order ris—and Elizabeth Warren, Sta

But in our chapter on fictional CBS’ “Madam Secretary;” Fox is restored by a White male— cey Abrams and others who women presidents on screen, we 21’s “Homeland;” Netflix’s “24’s” Jack Bauer and the male announce their eagerness to found something particularly “House of Cards;” and HBO’s vice president in “Homeland.” serve—requires recognizing relevant to the coverage of the “Veep.” HBO’s “Veep” takes the premise the diverse forms that backlash Democratic Party “veepstakes.” It may seem like a small point, of a craven woman politician to against women’s political amWomen who are politically ambibut when showrunners want to an absurd extreme, with actress bitions can take, which span

from calling a congresswoman a “f—— b—-” on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to portraying women presidents as Machiavellian on television dramas.

Did pop culture cause those Biden funders to unsuccessfully try to undermine Harris?

No. But the stories we tell ourselves on screen have taught us that women who actually want to be president can’t be trusted. That might be why people like Ambassador Susan Rice, who’s never run for office, and Congresswoman Karen Bass, who said she doesn’t want to run for president, landed on Biden’s short list to favorable coverage.

“At every step in her political career,” The New York Times wrote of Bass, “the California congresswoman had to be coaxed to run for a higher office. Now she’s a top contender to be Joe Biden’s running mate.”

Men who run for president typically have to demonstrate the requisite desire—the socalled “fire in the belly.”

Bizarrely, women are supposed to act like they don’t even want it.

Karrin Vasby Anderson is a professor of communication studies at Colorado State University.

—This story was republished by

It’s like eyewitnessing a car crash, going into shock and living through the outcome.

him and those around him. His they experienced but by their innocence and tragic murder successful fight for justice. It’s a made him a martyr who was eumessage that should encourage logized at his funeral: “God takes BLM activists. permission from The Conversation. those who are not pure.” For that HBO premiered ‘Yusuf Hawkins: to be true, lessons and principles ‘Storm Over Brooklyn’ on August 12. have to be learned by those left It began streaming on HBO Max on

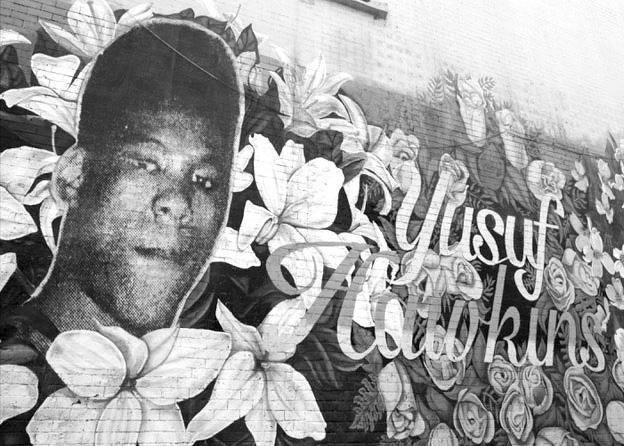

Mural dedicated to Yusuf Hawkins

Photos courtesy of HBO

August 13. Check your local listings for showtimes.

Dwight Brown is an NNPA News Wire film critic. Find more of his work at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.