11 minute read

Chapter 4 King of the Garment District

Working at a borrowed desk in the office of a general contractor he knew, Natey Kandal, Kleinberg set out to take on the Garment District single-handedly. He had his own excellent reputation, something of a following, and many brokers as contacts he cultivated over the years working under Gerstl’s tutelage.

“I had good leads and I wouldn’t have gone into business without them,” Kleinberg says. “The brokers were the ones who recommended me.”

Advertisement

He was known as hard-headed and detail-oriented, never leaving a job site until everything met his specifications. He also had a vision of what he wanted his firm to become.

“When I founded the firm in 1959, I established a set of guiding principles that would form the foundation of all of its work,” Kleinberg explains. “These principles— commitment, focus, excellence and integrity—continue to guide our work decades later.” Clients trusted him and never hesitated to recommend him for other jobs. It was another skill he had, however, that got him his big break: he spoke German. When word got around that Lufthansa, the German state airline, needed a firm to design new offices and streetlevel Fifth Avenue ticket center, a broker recommended

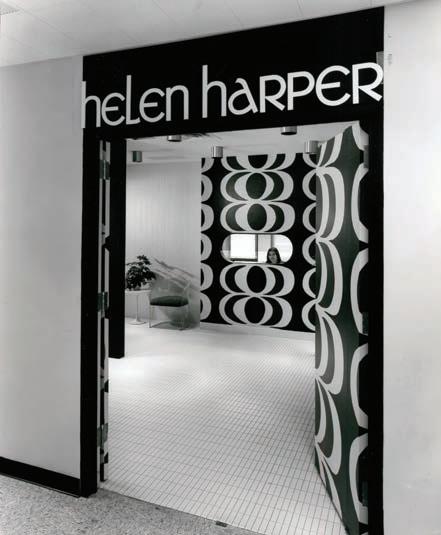

Interior of the Lufthansa ticket office.

Exterior of Lufthansa at night, this page; opposite page, the interior.

Lufthansa ticket agents at work.

Kleinberg. As a German speaker, he was able to put the Lufthansa people at ease and he got the job.

“The entrance to the ticket office and the interior was my first real architectural project,” he recalls. “It was one of my most beautiful designs.”

The success and visibility of that commission led to more and more recommendations from brokers. Smaller jobs were an entrée to showrooms and larger commissions, all blank canvasses for a wealth of original ideas.

Kleinberg quickly became known as King of the Garment District, that slice of Manhattan’s West Side where the booming clothing industry located its design studios, showrooms and sales offices. Women’s Wear Daily sang his praises in article after article, so vast was his influence in the business. Many of the brands he designed for were just starting out, and as they grew, Milo Kleinberg Design Associates grew with them, following them to bigger spaces as they expanded. Brokers were happily complicit in all the moves and designs of new facilities. His knack for marketing office space led to signed leases.

“What changed for me was meeting a lot of brokers who needed my advice on how to subdivide spaces to meet clients’ needs, explaining and showing them how they could fit into any particular space,” he says. “That was my talent: calculating 5,000, 10,000, 50,000 square feet and subdividing it in the best, most costeffective way possible. “I never said anything just to get them in and design the space,” he continues. “I was honest with the client and with the broker, both of whom depended on me to do a layout that would work for them.”

He had an uncanny ability to size up a floor plate immediately. “It just came naturally to me,” he says.

Irving Geffner worked with Kleinberg from the 1950s, when they were both starting out, until his retirement in the late 1990s. Geffner’s father owned a company called Commercial Cabinet, which supplied architectural woodwork, furniture and built-ins for the kind of interiors that were Kleinberg’s specialty. “We were the Rolls Royce of the industry,” Geffner says.

When Kleinberg struck out on his own, he asked Geffner to join him in the business. Geffner demurred, preferring to work with his father in a company that he would eventually inherit. He went on to be Kleinberg’s go-to supplier of cabinetry and furniture on most of his important commissions for the better part of three decades. They remain friends today.

Geffner recalls how

ambitious Kleinberg was, 1407 Broadway, the Garment District landmark.

but also how he could conjure up design solutions with lightening speed, sketch them out and get them to the client.

“He understood the client’s needs very quickly, then would draw something up and have it to the client the next day,” says Geffner, whose own clients included the storied Schrafft’s restaurants, American Express and Hunting World retail stores, in addition to work for architects I.M. Pei and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), and furnishings for the restoration of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. “He was always thorough and professional and detail-oriented, from coat hooks on the backs of doors to incidentals like paintings and sculptures,” Geffner remembers. “His follow-through was extraordinary.”

Geffner also recalls Kleinberg as a nimble problem solver. “We were photographing a job we’d just finished, with my wife as a model, when I tripped on a wire, pulled a lamp over and burned the brand new carpet. Milo said, ‘Leave it to me.’ The next day we went back and he’d rearranged all the furniture to cover the burn as though nothing happened.”

The client didn’t see the burn and loved the job.

1411 Broadway. Kleinberg had the damaged carpet repaired a few days later.

The development of the integrated project management approach became a boon for Kleinberg, whose landlord clients increasingly turned to him for advice on how to best divide up space. One building in particular was key to ensuring the designer’s reputation, 1411 Broadway, which opened in 1970. Owned by Swig & Weiler (which later became Swig, Weiler & Arnow), and designed by Irwin Chanin, a prolific builder and architect of the era credited with the Chanin Building and the Roxy and Beacon theaters, it was modern, state of the art, and as a landmark in the Garment District. It would also compliment 1407 Broadway, which opened in 1959 and was already home to a number of clothing concerns. Yet

for some reason, space in 1411 was slow to rent. Slow, that is, until Kleinberg came up with the idea to cast the nets wider to appeal to a broader pool of prospective clients.

Management took his advice. He went to work using the same business scheme that had worked so well for him over the first decade of the life of Milo Kleinberg Design Associates, winning over prospective tenants by working with each individually, analyzing their needs, predicting future growth and designing a space just right for them. The building was eventually completely, with Kleinberg’s marketing acumen being credited for the leasing of some 80% of the units, and designing many of the interiors. Interior designer Rhoda Astrachan, whom he met at the beginning of his tenure with Max Gerstl, worked with him. It was the beginning of what would be a decades-long collaboration.

Kleinberg was also instrumental in developing a critical aspect of the new building that would sway a lot of prospective tenants: the permission to design and fabricate garment samples on the premises. Back then, sample making was considered manufacturing and, therefore, forbidden by the New York City Department of Buildings in an office building of 1411’s classification. To get the building code changed, Kleinberg testified before city officials and helped win the building a new kind of Certificate of Occupancy. Pattern and sample making were subsequently allowed, thus streamlining the process of getting a line to market and cutting costs in the bargain.

“After that, he designed spaces for a majority of the fashion tenants at 1411,” his son Jeffrey recalls.

The building was also where Kleinberg cemented his reputation for innovative showroom design. Working with staff, he developed new, original ways to display garments in showrooms, which, until then, relied rather unimaginatively on basic rods, rolling racks and hangers. For such high-profile fashion brands as Bobbie Brooks, Gloria Vanderbilt and College Town, Kleinberg devised spaces that were open but separated by interesting dividers, so multiple sales people could work simultaneously with retail buyers.

Another innovation to Kleinberg’s credit was the early use of glass partitions, as office design started to move away from expensive build-outs with an enclosed office for each executive. At first, they were glass panels in traditional wooden surrounds fabricated by Commercial Cabinet to coordinate with the traditional wooden furniture that was popular at the time. Over the decades, glass evolved into the go-to material for partitions to allow light and the feeling of spaciousness in offices that seemed to be getting smaller and smaller. Glass paired with wood as imagined by Kleinberg is now coming back into vogue. “People are using the wood surrounds again, like in a project we’re designing at 444 Madison Avenue,” notes Jeffrey. “My father has been using glass this way since he started in the business.” Kleinberg’s work in the Garment District extended to innovative ways to display merchandise in showrooms that retailers could then apply in-store. To Jeffrey, this was his father’s own brand of genius: he had a good eye that extended beyond his own specific discipline into clothing, textiles and industrial design, as well as all aspects of interior design. “He was multi-talented and could understand how buyers needed to see the clothes,” Jeffrey says.

In Geffner’s view, thanks to Kleinberg, it was no longer business as usual.

“He was in the thick of things, not at all old-fashioned, always innovative and up-to-date on contemporary design trends,” Geffner says. “He had a great eye for making the merchandise stand out. You never saw the background—your focus was on the article.”

“I was able to design the space, design different rooms within a showroom,” Kleinberg recalls. “Within two years I was the King of the Garment District.”

“From that point on, I knew I was successful,” he says. “I just wanted to move ahead and grow the company.”

He was also leading a comfortable life. In 1969, Kleinberg, his wife Bertha, Jeffrey and Michael moved into a brand new, two-bedroom mid-century modern apartment building with views of the Hudson River in Riverdale. Called Hayden on the Hudson, it represented

Bathing suit showroom with tiger print chairs.

Innovative glass partitions in an apparel showroom.

the best of contemporary residential architecture, complete with a swimming pool and tennis courts. It was designed by noted architect Henry Kibel and built by Wechsler & Schimenti. Kleinberg himself designed the interior of the family’s fourth-floor unit, where he still lives today.

According to Michael, his father had his heart set on a house in Fieldston, the lush and more upscale swath of Riverdale, but his mother preferred apartment living.

“There were plenty of homes for sale in Fieldston at the time, but she had a fear of being in a house alone,” Michael explains. “It dated back to her childhood in the family farmhouse in Bavaria, when the Nazis were a constant threat.”

Milo Kleinberg Design Associates was a decade old by this time. Kleinberg and Bertha, both of whom came to the U.S. with nothing, enjoyed their new prosperity as anyone would. They travelled a great deal, often to Europe or on cruises. Later on, the family had weekend houses in the Catskill Mountains where they would go for much of the summer, as well as on weekends in spring and fall and for ski outings in winter.

It was during this time that Kleinberg first became active in philanthropic causes, many of which continue to benefit from his generosity decades later. He has done pro bono design consulting for the Riverdale Jewish Center and contributed to the SAR Academy in Riverdale, in addition to being involved with Israel Bonds. He was honored in 2007 by Ronald McDonald House, and also honored by Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem.

Philanthropy is something of a Kleinberg family tradition. Jeffrey provided pro bono consulting services for the 150-seat theater at the Westchester JCC, and was instrumental in the design and expansion of the Young Israel of Scarsdale synagogue. He and his wife, Ellyn, are very active in the Westchester Day School, where they headed an initiative to design and build a classroom for children with special needs.

Michael met his wife, Arlene, on a boat ride for young donors to United Jewish Appeal (UJA), and today serves on the board. The firm supports the Jerusalem-based SHALVA, the Association for Mentally and Physically Challenged Children, where a plaza is dedicated to Bertha Kleinberg. They give annual year-end gifts to the institution as a holiday initiative.

According to Michael, family philanthropy goes back to well before his father achieved any kind of professional success. His maternal grandparents often visited people in hospitals and gave modest amounts, even when they had less than nothing.

“When she passed away, there was an envelope with money in it for charity,” he recalls.

College Town ladies’ apparel showroom with partitions designed to display garments.