11 minute read

A HERO'S LIFE

Saturday, September 13, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Sunday, September 14, 2025 at 2:30 pm

ALLEN-BRADLEY HALL

Ken-David Masur, conductor

Stewart Goodyear, piano

ANDREA TARRODI

Festouvertyr

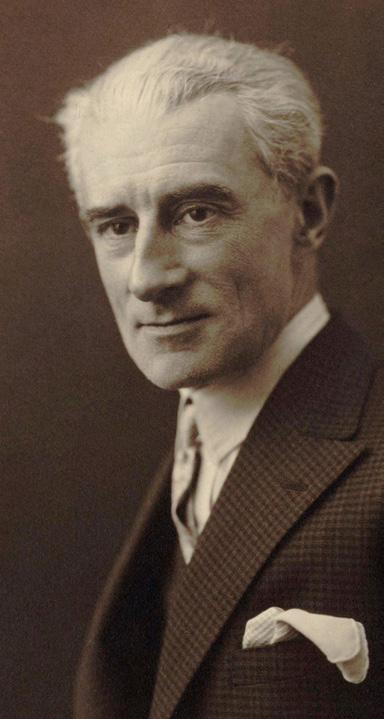

MAURICE RAVEL

Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major, M. 82 Stewart Goodyear, piano

INTERMISSION

RICHARD STRAUSS

Ein Heldenleben [A Hero’s Life], Opus 40, TrV 190

I. Der Held [The Hero]

II. Des Helden Widersacher [The Hero’s Adversaries]

III. Des Helden Gefährtin [The Hero’s Companion]

IV. Des Helden Walstatt [The Hero at Battle]

V. Des Helden Friedenswerke [The Hero’s Works of Peace]

VI. Des Helden Weltflucht und Vollendung [The Hero’s Retirement from this World and Completion]

Jinwoo Lee, violin

The MSO Steinway was made possible through a generous gift from MICHAEL AND JEANNE SCHMITZ. The 2025.26 Classics Series is presented by the UNITED PERFORMING ARTS FUND and ROCKWELL AUTOMATION

The length of this concert is approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes.

Guest Artist Biographies

STEWART GOODYEAR

Proclaimed “a phenomenon” by the Los Angeles Times and “one of the best pianists of his generation” by The Philadelphia Inquirer, Stewart Goodyear is an accomplished concert pianist, improviser, and composer. Goodyear has performed with, and has been commissioned by, many of the major orchestras and chamber music organizations around the world.

Last year, Orchid Classics released Goodyear’s recording of his suite for piano and orchestra, Callaloo, and his piano sonata. His recent commissions include works for violinist Miranda Cuckson, cellist Inbal Segev, the Penderecki String Quartet, the Horszowski Trio, the Honens Piano Competition, and the Chineke! Foundation. Goodyear made his BBC Proms debut performing Callaloo with the Chineke! Orchestra under Andrew Grams in the fall of 2024.

Goodyear’s discography includes Beethoven’s complete sonatas and piano concerti, as well as concerti by Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, and Prokofiev, an album of Ravel’s piano works, and an album, entitled For Glenn Gould, which combines repertoire from Gould’s U.S. and Montreal debuts. His recordings have been released on the Naxos, Marquis Classics, Orchid Classics, Bright Shiny Things, and Steinway & Sons labels. Goodyear released his recording of concerti by Mendelssohn and Schumann, along with two of his original compositions, on Orchid Classics in February 2025.

Highlights for the 2025-26 season are his performances at the Rheingau Musik Festival, the Stratford Music Festival, and performances with Philharmonie Südwestfalen, the St. Louis, Winnipeg, and Virginia Symphonies, and A Far Cry in Boston. He will also perform in recital on the Eastman Piano Series and at the Gilmore Piano Festival.

Program notes by David Jensen

ANDREA TARRODI

Born 9 October 1981; Stockholm, Sweden

Festouvertyr

Composed: 2021

First performance: 3 December 2021; Anja Bihlmaier, conductor; Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra

Last MSO performance: MSO Premiere

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons (2nd doubling on contrabassoon); 4 horns; 3 trumpets; 2 trombones; bass trombone; tuba; timpani; percussion (bass drum, snare drum, suspended cymbals); harp; strings

Approximate duration: 4 minutes

At the forefront of contemporary composers breaking new sonic ground in the 21st century, Andrea Tarrodi’s music has been heard on five continents and has been performed by some of the world’s finest orchestras, including the BBC Philharmonic, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, among many others. Characterized by their shimmering textures, breathtaking naturalistic effects, and nuanced shadings, her works have resounded throughout classical music’s most prestigious concert halls, including the Barbican Centre, Royal Albert Hall, and Vienna’s Musikverein.

Tarrodi’s formal studies took her to the Piteå School of Music in northern Sweden, where she studied composition and arranging, the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, and the “Francesco Morlacchi” conservatory in Perugia, Italy, before returning to the Royal College to complete her master’s degree in composition in 2009. A frequent prizewinner, Tarrodi’s album of string quartets, recorded by the Dahlkvist Quartet, received a Swedish Grammy Award for Best Classical Album of the Year in 2018 — the same year her piano concerto Stellar Clouds was named Classical Music of the Year by the Swedish Music Publisher’s Awards.

Written on a commission from the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Festouvertyr (which loosely translates to “Festive Overture”) honors the 25th anniversary of the Sten A. Olsson Foundation for Research and Culture, a charitable organization devoted to funding innovations in science, technology, medicine, and the humanities. Tarrodi, who has synesthesia (a condition in which one sense perception can act as a catalyst for a secondary sensory experience), has described her approach to composition as visual in nature, associating particular chords and pitches with certain colors and illustrating her musical ideas in drawings and paintings; in four exhilarating minutes, Festouvertyr leverages this remarkable sensitivity to instrumental timbre while delighting in its own strikingly original soundscape.

Beginning with a brassy fanfare in quartile harmonies and a flurry of silvery scales, bristling woodwinds sound polyrhythmic harmonies as the sweeping plush of the accompanying strings and soaring voluntaries in the trumpets blend into a wash of sound, calling to mind the verdant, kaleidoscopic scores of Jean Sibelius. Even as Baroque fragments of the “Nobel Fanfare” (originally derived from music by André Danican Philidor, a French composer who served the royal family at Versailles) and Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks flitter about, the music gives the impression of a glowing, spacious landscape depicted in purely aural terms. Rather than concluding with bombast or spectacle, the music simply dissolves into silence as the suspended cymbals wash away the watercolor splendor of this delightfully crafted miniature.

MAURICE RAVEL

Born 7 March 1875; Ciboure, France

Died 28 December 1937; Paris, France

Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major, M. 82

Composed: 1929 – 1930

First performance: 5 January 1932; Robert Heger, conductor; Paul Wittgenstein, piano; Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Last MSO performance: 18 September 1977; Kenneth Schermerhorn, conductor; Michel Block, piano

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling on piccolo); 2 oboes; English horn; 2 clarinets; E-flat clarinet; bass clarinet; 2 bassoons; contrabassoon; 4 horns; 3 trumpets; 3 trombones; tuba; timpani; percussion (bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tam-tam, triangle, wood block); harp; strings

Approximate duration: 19 minutes

By the late 1920s, Maurice Ravel was widely recognized as one of the greatest musical magicians of his generation. A fine pianist with an incomparable mastery of instrumental color and a seemingly boundless imagination, his diaphanous orchestral scores offered glimpses of a luminous, ethereal world just beyond the stage. Seemingly unconcerned by matters of wealth or critical success — despite his status as the most celebrated French composer of his day — his music was the fruit of a slow, meticulous, and intelligent creative process that prompted Igor Stravinsky to describe him as “the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers.”

The cataclysm of World War I, followed by the death of his mother in 1917, significantly diminished Ravel’s productivity, and in 1921, he left his life in the city behind to settle in a small home on the outskirts of Montfort-l’Amaury. Despite the slower rhythm of his life in the countryside, Ravel began touring as a pianist with greater frequency throughout the 1920s, and the few works he did compose in the postwar years of his life remain some of his most inspired realizations. His successful tour of North America in 1928, colored by its vibrant cityscapes and the tantalizing sounds of jazz, left an enormous impression: having already composed a wealth of ravishing music for the piano, he decided he would, in his sixth decade, author his first piano concerto. He would soon unwittingly find himself in the position of writing two at the same time.

Like Ravel, the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein had been indelibly altered by the Great War. He had just made a successful public debut in Vienna in 1913 when the war arrived, and by August 1914, he was taken prisoner of war by the Russians after having had his right arm amputated on the battlefield. When he returned to Austria as part of prisoner exchange in 1915, he began commissioning left-handed works from a wide variety of composers, including Hindemith, Britten, Prokofiev, and Strauss, though it was Ravel’s brooding, incandescent score that would eventually find favor as the most popular work in Wittgenstein’s new repertory. Ravel set aside the draft he had begun for himself (what would eventually become the jazz-inflected piano concerto in G), but the collaboration was fraught with conflicts of personality. Wittgenstein objected to the lengthy cadenza in the concerto’s introduction, telling Ravel that “If I wanted to play without the orchestra, I wouldn’t have commissioned a concerto!” Wittgenstein made matters worse by cutting and rewriting entire passages, shocking Ravel by performing his heavily revised “interpretation” at the French embassy in Vienna ahead of its premiere. To both their displeasure, Ravel eventually convinced Wittengenstein to play the work as written.

Unlike the extroverted, high-flying theatrics that characterize his concerto in G, its left-handed counterpart is made up of churning, dusky music which probes the depths of its own contents: “From the opening measures,” the musicologist Henry Prunières wrote, “we are plunged into a world in which Ravel has but rarely introduced us.” Composed as a single continuous movement, the opening measures give the impression of a subterranean world, rising as it does from the depths of the orchestra before erupting in a tremendous cadenza elaborating upon the first section’s primary musical material. The center of the concerto is a martial, spritely scherzo that draws on the incisive rhythms and piquant harmonies of American jazz, and the work reaches its apotheosis as Ravel interweaves the concerto’s themes into a sensuous, shimmering cadenza before a final fanfare from the orchestra draws the music to its earth-shattering conclusion.

RICHARD STRAUSS

Born 11 June 1864; Munich, Germany

Died 8 September 1949; Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Ein Heldenleben [A Hero’s Life], Opus 40, TrV 190

Composed: July – 27 December 1898

First performance: 3 March 1899; Richard Strauss, conductor; Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester

Last MSO performance: 22 January 2011; Edo de Waart, conductor Instrumentation: piccolo; 3 flutes; 4 oboes (4th doubling on English horn); 2 clarinets; E-flat clarinet; bass clarinet; 3 bassoons; contrabassoon; 8 horns; 2 piccolo trumpets; 3 trumpets; 3 trombones; tenor tuba; tuba; timpani; percussion (bass drum, cymbals, military drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tenor drum, triangle); 2 harps; strings

Approximate duration: 40 minutes

Strauss’s eighth tone poem arrived at the close of the 19th century as the artistic high point of his revolutionary efforts in the genre. Comparable in scope and peculiarity only to Hector Berlioz’s phantasmagorical Symphonie fantastique, Ein Heldenleben capitalized on the coloristic and textural palettes now accessible by means of the newly modernized orchestra, calling for an enormous battery of instrumentalists in painting an unabashedly self-referential portrait of the artist’s life. While Strauss equivocated throughout his life as to whether or not the work was in fact autobiographical in nature, it’s difficult to extricate the megalomaniacal image of the composer from a piece containing dozens of musical quotations from his own canon.

Not without resistance from the intellectual public, the very last years of the century had enshrined Strauss in Europe’s musical spheres as the de facto emissary of modern music. In a span of five years, an enormous body of tone poetry and lieder flowed from the composer’s pen, transmuting the emotive urgency of the Romantics into a new, wildly imaginative medium. It was during a stay at a Bavarian resort in the summer of 1898 that he began to conceive of a work in the vein of Beethoven’s Eroica which was to represent, in his own words, “not a single poetical or historical figure, but rather a more general and free ideal of great and manly heroism.”

While Strauss himself was only responsible for the individual titles of each movement (which he would later request be struck from subsequent publications, preferring his work to be evaluated on purely musical terms), the implied narrative of the piece has been widely interpreted by audiences as a depiction of Strauss’s personal rivalry against Germany’s musical critics, colored by the Nietzschean conflict between the self-actualized individual and his place in civil society. The “adversaries” of the second movement, portrayed by chattering woodwinds and low brass, are the same detractors that take the hero to war, a battle distinguished by its thundering fanfares and halted only by the hero’s “works of peace,” wherein Strauss liberally intersperses themes from his opera Guntram, no less than six of his tone poems, and two art songs.

At the center of the drama is the artist’s “companion,” acknowledged by the composer as a direct illustration of his wife, Pauline de Ahna; her role, alternately capricious and poignant, is assigned to the concertmaster, whose elaborate cadenzas embody the woman Strauss described as “very complex, a trifle perverse, a trifle coquettish, never the same, changing from minute to minute.”