3 minute read

The Right to Representation: Coming to a

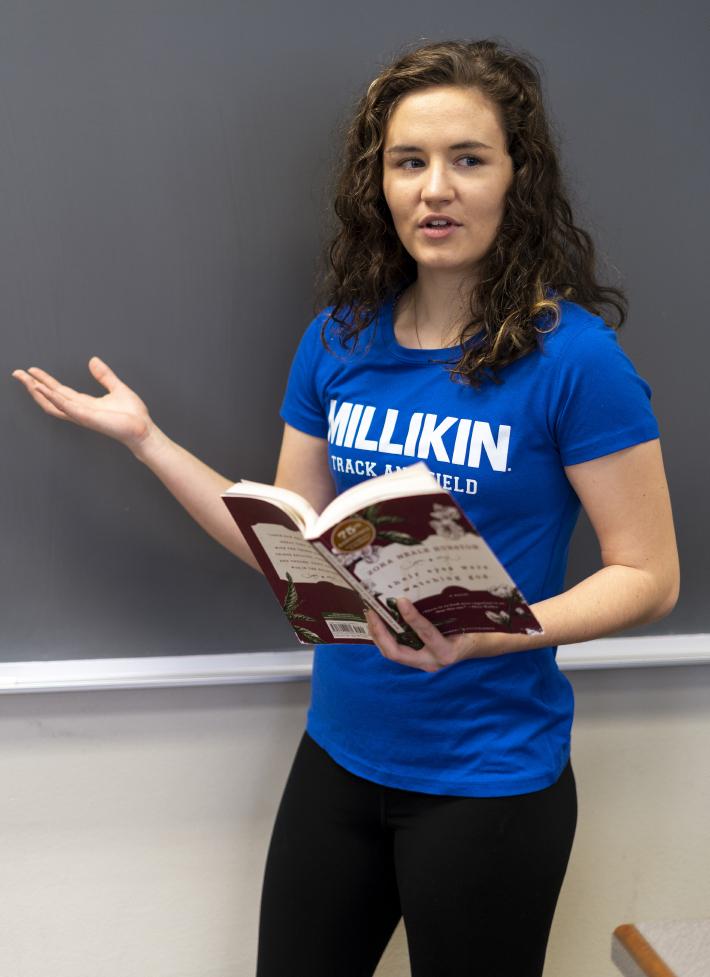

“W henever I give a presentation on ranked choice voting, I ask people to raise their hand if they think things are going well politically. Nobody has ever raised their hand,” says Ben

Chapman, a local political activist. Chap- man serves as the leader of a grassroots

Advertisement

organization known as Illinoisans for Ranked Choice Voting.

When the Founding Fathers constructed the United States Constitution in 1787, modern democracies hadn’t fully developed yet, and the few that existed often failed badly. It is by some stroke of luck that our Constitution and electoral system have lasted 243 years. However, since the birth of our nation, republics around the world have changed significantly, and so have we. Now, it’s not unusual to see mayoral elections with nearly ten candidates. Presidential primaries have turned into epic gladiatorial fights where two dozen candidates enter the battle, and only one survives.

This, according to Chapman, is at least one of the reasons why no one raises their hand when he asks if they think everything is going well in government. America has long used a plurality election system where whoever gains one more vote than the next candidate becomes the winner. This has created an electoral system that forces many to choose between the lesser of two evils. Ranked

Choice Voting (RCV) allows you to rank the candidates in order from favorite to least favorite.

If the first candidate on your list doesn’t clear the 50 percent vote threshold, your vote goes to the next candidate until someone can inch past 50 percent of the vote. According to Chapman, “One of the most powerful arguments for Ranked Choice Voting is having someone fill out a ballot because they see that you don’t have to vote strategically. You vote for who you like.”

Who wouldn’t want to vote for who they like—especially in the primaries? In the last presidential election, the Republicans had a crowded primary. This time, the Democrats have their pick of the litter. The problem is that it can be hard to vote for who you like best rather than who you think can win the general election. You may like Andrew Yang the best out of all the candidates yet still vote for Joe Biden because you don’t want to “waste” your vote. In the worst cases, similar candidates such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders can cannibalize their own voter base. That’s the problem with our current system, according to Chapman. “Right now we aren’t electing the candidates that people would be happy with. An electoral system should be designed to increase voter expression,” he says. When voters have to do 3-D chess at the ballot box to determine who they both like and know can win, they experience a form of voter suppression.

Critics of Ranked Choice Voting have claimed anything from “it changes the Constitution” to “it allows more than one vote per person.” It’s true that Ranked Choice Voting isn’t as straightforward as plurality voting. But that doesn’t mean it changes our Constitution, makes our election system vulnerable, or gives more than one vote to anybody. “A lot of criticisms are based in misunderstanding,” Chapman shares. “RCV does not allow more than one vote per person. It doesn’t change our constitution—it optimizes our electoral system.”

This is why states like Illinois are looking to use RCV in their elections. Maine has already implemented it across the board and

used it in 2018. Many in the state of Massachusetts are trying to bring it statewide. The city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, used ranked choice voting for the first time in 2018. Cities in states including California, Colorado, Maryland, and Minnesota are all using RCV. In doing so, legislators offer greater democracy to their constituents and empower their political voice. Voters can go to the ballot box with the knowledge they can vote for whomever they like best rather than the lesser of two evils. MILLIBITS